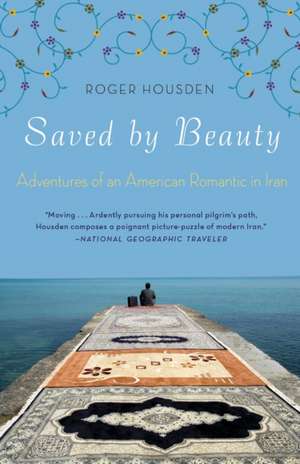

Saved by Beauty: Adventures of an American Romantic in Iran

Autor Roger Housdenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 12 noi 2012

When Roger Housden decided to travel to Iran and finally see the subject of his youthful fascination, he was in his sixties. By then, he thought he had seen the world. He was wrong.

It was a quest that changed him forever. In Iran, Housden met with artists, writers, film makers and religious scholars who embody the long Iranian tradition of humanism, and shared with him their belief in scholarship and artistry. From the bustle of modern Tehran to the paradise gardens of Shiraz to the spectacular mosques and ancient palaces of Isfahan, Housden met Iranians who were warm, welcoming, generous, intellectually curious, and altogether alive with their love for one another, and for the faith and tradition that holds them together.

Saved by Beauty weaves a richly textured story of many threads. It is a deeply poetic and perceptive appreciation of a culture that has endured for over three thousand years, while it also portrays the creative and spiritual cultures within contemporary Iran. While there, Roger Housden was brought face to face with the reality that beauty and truth, deceit and violence, are inextricably mingled in the affairs of human life, and was forever altered by it.

Preț: 106.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.41€ • 21.38$ • 16.87£

20.41€ • 21.38$ • 16.87£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307587749

ISBN-10: 0307587746

Pagini: 290

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307587746

Pagini: 290

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

ROGER HOUSDEN is the author of some twenty books, including the best-selling Ten Poems series and the novella Chasing Rumi. English by birth, he has been a writer for the Guardian and an interviewer for the BBC. Housden emigrated to the States in 1998 and now lives in the Bay Area. Visit himat www.rogerhousden.com

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Both readers new to Housden and fans of his poetry will treasure this memorable account of what may be a once-in-a-lifetime trip. Even better, his insights are also sure to inform and maybe even re-form preconceived notions many hold about Iran. It is impossible not to lose oneself in Housden's many-faceted narrative."

—Booklist, starred review

"A lyrical panorama of contemporary Persian politics and culture, this book gives contour and nuance to our idea of Iran, and introduces us to complex, very memorable characters."—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“The eloquent account of a Western poet’s encounters with the land, culture and people of Iran...soulful and uplifting.”—Kirkus Reviews

“Moving…Ardently pursuing his personal pilgrim’s path, Housden composes a poignant picture-puzzle of modern Iran.” ߝ National Geographic Traveler

From the Hardcover edition.

—Booklist, starred review

"A lyrical panorama of contemporary Persian politics and culture, this book gives contour and nuance to our idea of Iran, and introduces us to complex, very memorable characters."—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“The eloquent account of a Western poet’s encounters with the land, culture and people of Iran...soulful and uplifting.”—Kirkus Reviews

“Moving…Ardently pursuing his personal pilgrim’s path, Housden composes a poignant picture-puzzle of modern Iran.” ߝ National Geographic Traveler

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

Writing Iran

The inner—what is it?

If not intensified sky, hurled through with birds

And deep with the winds of homecoming.

—Rainer Maria Rilke

Whenever I think of the color blue, I think first not of the sea or the sky, but of a dome. A dome in Isfahan, Iran. It lodged itself in my mind some thirty-five years ago, one gray afternoon in the British Library, that beautiful building, itself a dome, which at the time housed a few million books and manuscripts on every subject known to man. Oblivious of the scholars shuffling to and fro around me, I gazed for the longest time at a full-color plate of the dome of the Royal Mosque in Isfahan. Its perfection of shape and its blue never left me. It prompted me from that time on to marvel at domes, to appreciate their sensuous precision with a fresh eye, and to love that turquoise blue with a single-mindedness that has dominated my wardrobe and my wall hangings for a lifetime.

It was my Iran phase. Around the same time, I discovered Iranian music and poetry. While my peers were listening to the Stones and Bob Dylan, I would be poring over the Iranian music section of some esoteric record store in London, looking for ethnic folk music or the music of the Sufis, the mystical brotherhoods of Islam. Or I would be in the Middle Eastern Bookshop on Museum Street, looking for translations of the great Iranian Sufi poets, Rumi and Hafez. That music, those poems, had a visceral effect on me. They would bring me down into myself, into my body and the rhythms of my blood: another kind of heart murmur, you might say.

It made for a potent brew; a jumble of feelings and images that somehow conjured the fantasy of a culture that was both sensuous and soulful at one and the same time. For all I knew, my imaginings were mere imaginings. The Shah was in charge then, and his mission to modernize his country made the images of my inner world seem old-fashioned at best, and reactionary at worst. It wasn’t cool in Iran then to have an interest in Sufis or anything non-Western. My fascination was probably no more than a young man’s longing for a romance and vitality that seemed hard to come by under the somber skies of his native London—a much grayer city then than it is now.

Even so, those images of Iran remained through my lifetime, alive and innocent though never tested by reality. Those colors, that music, that poetry, the beautiful dome, I realize, represented my own personal paradise; a paradise that is neither here nor there, of course, but rather a living sense of presence in which nothing is lacking. A sort of homecoming, you might say.

Those same images linger today in the Persian art on my walls: a large ceramic tableau of overflowing flowers that I bought years ago, and a detailed embroidery, a meter high, of the Tree of Life complete with birds of paradise, that I gave myself from the proceeds of my first book contract. My Iran phase never really went away; neither, it seems, did my nostalgia for the original “home.”

We never know until it happens how the images stored in our brains may suddenly leap up out of nowhere to shape our lives. Thirty-five years later, in the early spring of 2008, I was walking through the redwoods near my home in California with nothing in my mind other than the savor of the forest and the deep trees. I wasn’t walking as a writer in search of a subject, even though I had no idea what my next book might be. I was in the positive gap, the one that is empty of content, yet seems to sustain you, like floating in the Dead Sea—as opposed to the kind of gap where you can go into free fall down some endless rabbit hole.

Walking along that path through the woods, my mind was in neutral. Into that empty space, out of nowhere, three words sprang fully formed into my mind: the other Iran. I do not know where that phrase came from. I was strolling along with the clouds above and the ground below. My images of Iran had not surfaced for years.

It seems to be one of life’s enduring habits to sneak up on us unawares. My next project or enthusiasm (they are usually one and the same) has always arrived unannounced and from left field, rather than through any deliberate attempt to figure it out with pen and paper. Not that I don’t try every now and then to dream up subjects and passions I could turn into a piece of work—but they rarely, if ever, materialize that way.

So here I was, embarking on my sixties, out of a second marriage for three years, with a rewarding but precarious occupation that dispenses with the need for a weekly planner, not to mention a yearly one: an occupation that encourages me to follow the lightning wherever it strikes, and in the lightning’s time, not mine. I had recently finished writing a long series of books on poetry, and once again, a variant of the perennial question—What do you want to do now with your life?—had been flitting about the edge of my mind.

Except it was no longer about doing this or that so much as feeling which qualities and loves really mattered to me, and which I wanted to embody in this world before I left it. None of this was in the shape of an anxiety, or even in the form of words; but as a kind of readiness, or welcoming disposition toward something I could feel was wanting to surface.

Not that I was sitting back waiting for my life to happen. Of course I have wondered at times what on earth I am doing here; of course, as a writer, I have suffered the peculiar sensation, like grasping at air, of not having a subject. In the last couple of years I had flirted with several ideas that seemed promising book subjects. But nothing had had the wings to lift words onto the page.

That’s when the rabbit hole can appear out of nowhere: the gap that can open up without warning between the last book, the last painting or start-up project, and what you hope, at least, will be the next one. The kind of gap where you realize that sweating it out means what it says. I went through one of those gaps eighteen months or so before my walk in the woods, and not for the first time. I was having ideas all right; in fact I had ideas aplenty, but my publisher was not impressed. The Greatest Joy: Having a Purpose Bigger Than You Are. I don’t think so, she said. On Being Useful. Uh-uh. No. Ten Meals to Eat Before You Die: Journey to the Heart of France—how could anyone say no to that, I thought.

It would save my bacon, so to speak; give me a way forward, let me run round my favorite country for a year. I thought I would use food as the doorway into La France Profonde, the culture whose language and literature I loved. I thought it would give my writing career a kick-start into a new future. But no, they were not impressed.

“How can you not be impressed by ten meals to die for? Ten French meals?” my brother Mark had asked when I called to tell him. But then he lived in France, was something of a gourmand himself, and ran his own business, the French House, selling the romance of French style to Anglo-Saxons. It was he who had come up with the idea in the first place.

No, they were not impressed. Too regional, too French, too traditional. The publicity director killed it when she said she couldn’t see herself eating any of those meals. No confit de canard? Really? You don’t like the sound, let alone the taste, of bouillabaisse?

A writer’s life is about moving on. There’s always the hope of the next project, the next great idea. My previous book hadn’t turned out to be as great an idea as my publisher and I had hoped it would. Now the Ten Meals project had gone the same way before even getting off the ground. My agent tried to cheer me up as I was leaving New York after one of our periodic meetings.

“I have best-selling writers nowadays who have to propose four or five ideas before they get a green light,” she said consolingly. (How many more does that mean I have to go?) “It’s tough out there,” she told me. “People are not buying books the way they used to, so neither are publishers. They’re scared.” They’re scared! Don’t they know that being a writer with nothing to write about is like being a sailor without a boat, a builder without a hammer, a painter without a brush?

Back home from New York I sprawled on the sofa and gazed unseeingly out of the big window that looks onto one of the most beautiful landscapes I’ve ever beheld—Marin County, actually, with its big Mount Tam stuck right in the middle distance there before me among contours of pines and madrone trees. As I sat there, I let my eye travel down inward rather than outward for I don’t know how long, and let in the true horror of my situation—a writer without a subject, not so long without a wife, fresh from being madly in love with an unavailable woman, and with a most moderate bank account—and I started to smile.

I started to smile, and then I started to laugh. Maybe this was the end of the line for this particular writer, this couch on a Tuesday afternoon in May 2008. Maybe there was simply nothing left for him to say or write. And yet what would be wrong with that? I was still here, and more a lover of life than a survivor of it. I relaxed. Where a moment before I had felt empty, now I felt full. Not full of myself, in the way that I certainly can be, but full of relief, full of quiet, like after a big outbreath. I had enough money to live on for a year or so, and I would just see what if anything came out of the blue.

It was the other Iran that came out of the blue, several months later. I knew instantly that a big fish had surfaced, and that I was going to land it, and soon. When I reflect more deeply on the color blue, deeper still than the image of the dome in Isfahan, I realize that what it really means for me is the sea inside: the deep, uncharted waters of one’s own interior life, where unlived desires and loves swim and wheel and turn, calling to us, at times barely audible, at other times with a clarion call, to haul them up into the light before the light goes out.

When I reflect on what is still unlived in me, travel for its own sake, or out of simple curiosity, is not the first thing to come to mind. I have spent a substantial part of my life traveling the world. Nowadays I find the place where I live to be as full of curious customs and enchantments as anywhere. But then, those romanticized images of Iran from my youth had never dissolved, even if they had fallen below the surface; their lingering presence still exerted a magnetic pull that had now emerged in the form of words. Again my response wasn’t so much a decision as a realization, a strange elation at the dawning upon me of what was next: Oh! And now this! I felt, walking through those redwoods in Marin County, which is so beautiful there is surely no need to go anywhere: I am going to Iran! Of course! The power of adventure was upon me again.

As soon as those three words swooped into my mind, I knew the subject was far bigger in scope than my own personal curiosities and subjective story. In recent years Iran has been more at the forefront of people’s minds than almost any other country. It is never far from the front pages today, so that phrase, the other Iran, arose not only from my personal unconscious, but from the broader context of the current climate. Ever since the hostage crisis of 1979, America’s relations with Iran have been strained at best and dangerous at worst. But then it became the crux of the Axis of Evil, as George W. Bush proclaimed to the world. The mullahs, we were told, ran a quasi-fascist state full of terrorists that was on the verge of going nuclear, and that would be the ruin of all of us. With all the help from Ahmadinejad they could have wished for, the White House and the press succeeded in drawing a caricature of Iran that not only demonized an entire culture but dehumanized it.

The image of Iran as a dark and scary place, full of nuke-toting mullahs, remains a difficult one to dislodge from the collective imagination. And, especially in the light of Ahmadinejad’s tirades and intransigence, with good reason. Even more so, since, in June of 2009, the hopes of the Green Revolution were quashed in a stolen election and the violence that followed. And yet, paradoxically, what we also saw at that time on our screens was an Iran that so many Iranians themselves already knew their country to be: a young, vibrant, questioning, highly creative culture with dreams not so very different from our own.

This was the Iran, some six months before those fateful elections, that I wanted to bring to light—to touch and be touched by. I wanted to humanize its culture and its people in my own mind, to resist the temptation to objectify them as “other”—as a people somehow different from and inferior to us and therefore legitimate targets for our aggression; and also to help do something of the same for my readers. I wanted to look beyond the political wrangling altogether, to the truth and beauty of an ancient and sophisticated culture; to know something of life as it is lived there, beyond the slogans and the headlines; to touch the creative spirit of Iran and to be touched by it in turn.

Above all, I wanted to see if the Iran of today could give substance and value to the images I had cherished for decades. Those images—the poetry, the music, the Sufis, the soaring domes—are for me metaphors for wholeness. They have lingered through my lifetime because they represent a culture that embraced both its deepest longings and its delight in the sensuous world—a culture that in my imagination mirrored the possibility of my own synthesis of body and soul, soul and spirit. Finally, they represent a creative genius that has resulted in works of unparalleled beauty.

For my traveling companion I would take along Rumi, guide of souls. Rumi, the thirteenth-century Iranian poet I had been consulting for years—the one whose family had fled Iran before the Mongol hordes, and whose tomb now lay in the city of Konya, in Turkey. Of all poets, Rumi spoke my own heart to me. He knew the primordial sense of home I still hankered for. He knew the loss of it and also the union with it. He called it the “Beloved”; and he sang its praises as no one else has.

So, with Rumi in my pocket, I would set off to discover if the world I imagined was a current reality in Iran today, or merely a chimera of my own making; and if it did exist, whether it might still shine a light on the hidden truths of my own inner world. All this happened and more—more than I ever bargained for.

A couple of months after that walk in the redwoods, I was on a Lufthansa flight to Tehran.

From the Hardcover edition.

Writing Iran

The inner—what is it?

If not intensified sky, hurled through with birds

And deep with the winds of homecoming.

—Rainer Maria Rilke

Whenever I think of the color blue, I think first not of the sea or the sky, but of a dome. A dome in Isfahan, Iran. It lodged itself in my mind some thirty-five years ago, one gray afternoon in the British Library, that beautiful building, itself a dome, which at the time housed a few million books and manuscripts on every subject known to man. Oblivious of the scholars shuffling to and fro around me, I gazed for the longest time at a full-color plate of the dome of the Royal Mosque in Isfahan. Its perfection of shape and its blue never left me. It prompted me from that time on to marvel at domes, to appreciate their sensuous precision with a fresh eye, and to love that turquoise blue with a single-mindedness that has dominated my wardrobe and my wall hangings for a lifetime.

It was my Iran phase. Around the same time, I discovered Iranian music and poetry. While my peers were listening to the Stones and Bob Dylan, I would be poring over the Iranian music section of some esoteric record store in London, looking for ethnic folk music or the music of the Sufis, the mystical brotherhoods of Islam. Or I would be in the Middle Eastern Bookshop on Museum Street, looking for translations of the great Iranian Sufi poets, Rumi and Hafez. That music, those poems, had a visceral effect on me. They would bring me down into myself, into my body and the rhythms of my blood: another kind of heart murmur, you might say.

It made for a potent brew; a jumble of feelings and images that somehow conjured the fantasy of a culture that was both sensuous and soulful at one and the same time. For all I knew, my imaginings were mere imaginings. The Shah was in charge then, and his mission to modernize his country made the images of my inner world seem old-fashioned at best, and reactionary at worst. It wasn’t cool in Iran then to have an interest in Sufis or anything non-Western. My fascination was probably no more than a young man’s longing for a romance and vitality that seemed hard to come by under the somber skies of his native London—a much grayer city then than it is now.

Even so, those images of Iran remained through my lifetime, alive and innocent though never tested by reality. Those colors, that music, that poetry, the beautiful dome, I realize, represented my own personal paradise; a paradise that is neither here nor there, of course, but rather a living sense of presence in which nothing is lacking. A sort of homecoming, you might say.

Those same images linger today in the Persian art on my walls: a large ceramic tableau of overflowing flowers that I bought years ago, and a detailed embroidery, a meter high, of the Tree of Life complete with birds of paradise, that I gave myself from the proceeds of my first book contract. My Iran phase never really went away; neither, it seems, did my nostalgia for the original “home.”

We never know until it happens how the images stored in our brains may suddenly leap up out of nowhere to shape our lives. Thirty-five years later, in the early spring of 2008, I was walking through the redwoods near my home in California with nothing in my mind other than the savor of the forest and the deep trees. I wasn’t walking as a writer in search of a subject, even though I had no idea what my next book might be. I was in the positive gap, the one that is empty of content, yet seems to sustain you, like floating in the Dead Sea—as opposed to the kind of gap where you can go into free fall down some endless rabbit hole.

Walking along that path through the woods, my mind was in neutral. Into that empty space, out of nowhere, three words sprang fully formed into my mind: the other Iran. I do not know where that phrase came from. I was strolling along with the clouds above and the ground below. My images of Iran had not surfaced for years.

It seems to be one of life’s enduring habits to sneak up on us unawares. My next project or enthusiasm (they are usually one and the same) has always arrived unannounced and from left field, rather than through any deliberate attempt to figure it out with pen and paper. Not that I don’t try every now and then to dream up subjects and passions I could turn into a piece of work—but they rarely, if ever, materialize that way.

So here I was, embarking on my sixties, out of a second marriage for three years, with a rewarding but precarious occupation that dispenses with the need for a weekly planner, not to mention a yearly one: an occupation that encourages me to follow the lightning wherever it strikes, and in the lightning’s time, not mine. I had recently finished writing a long series of books on poetry, and once again, a variant of the perennial question—What do you want to do now with your life?—had been flitting about the edge of my mind.

Except it was no longer about doing this or that so much as feeling which qualities and loves really mattered to me, and which I wanted to embody in this world before I left it. None of this was in the shape of an anxiety, or even in the form of words; but as a kind of readiness, or welcoming disposition toward something I could feel was wanting to surface.

Not that I was sitting back waiting for my life to happen. Of course I have wondered at times what on earth I am doing here; of course, as a writer, I have suffered the peculiar sensation, like grasping at air, of not having a subject. In the last couple of years I had flirted with several ideas that seemed promising book subjects. But nothing had had the wings to lift words onto the page.

That’s when the rabbit hole can appear out of nowhere: the gap that can open up without warning between the last book, the last painting or start-up project, and what you hope, at least, will be the next one. The kind of gap where you realize that sweating it out means what it says. I went through one of those gaps eighteen months or so before my walk in the woods, and not for the first time. I was having ideas all right; in fact I had ideas aplenty, but my publisher was not impressed. The Greatest Joy: Having a Purpose Bigger Than You Are. I don’t think so, she said. On Being Useful. Uh-uh. No. Ten Meals to Eat Before You Die: Journey to the Heart of France—how could anyone say no to that, I thought.

It would save my bacon, so to speak; give me a way forward, let me run round my favorite country for a year. I thought I would use food as the doorway into La France Profonde, the culture whose language and literature I loved. I thought it would give my writing career a kick-start into a new future. But no, they were not impressed.

“How can you not be impressed by ten meals to die for? Ten French meals?” my brother Mark had asked when I called to tell him. But then he lived in France, was something of a gourmand himself, and ran his own business, the French House, selling the romance of French style to Anglo-Saxons. It was he who had come up with the idea in the first place.

No, they were not impressed. Too regional, too French, too traditional. The publicity director killed it when she said she couldn’t see herself eating any of those meals. No confit de canard? Really? You don’t like the sound, let alone the taste, of bouillabaisse?

A writer’s life is about moving on. There’s always the hope of the next project, the next great idea. My previous book hadn’t turned out to be as great an idea as my publisher and I had hoped it would. Now the Ten Meals project had gone the same way before even getting off the ground. My agent tried to cheer me up as I was leaving New York after one of our periodic meetings.

“I have best-selling writers nowadays who have to propose four or five ideas before they get a green light,” she said consolingly. (How many more does that mean I have to go?) “It’s tough out there,” she told me. “People are not buying books the way they used to, so neither are publishers. They’re scared.” They’re scared! Don’t they know that being a writer with nothing to write about is like being a sailor without a boat, a builder without a hammer, a painter without a brush?

Back home from New York I sprawled on the sofa and gazed unseeingly out of the big window that looks onto one of the most beautiful landscapes I’ve ever beheld—Marin County, actually, with its big Mount Tam stuck right in the middle distance there before me among contours of pines and madrone trees. As I sat there, I let my eye travel down inward rather than outward for I don’t know how long, and let in the true horror of my situation—a writer without a subject, not so long without a wife, fresh from being madly in love with an unavailable woman, and with a most moderate bank account—and I started to smile.

I started to smile, and then I started to laugh. Maybe this was the end of the line for this particular writer, this couch on a Tuesday afternoon in May 2008. Maybe there was simply nothing left for him to say or write. And yet what would be wrong with that? I was still here, and more a lover of life than a survivor of it. I relaxed. Where a moment before I had felt empty, now I felt full. Not full of myself, in the way that I certainly can be, but full of relief, full of quiet, like after a big outbreath. I had enough money to live on for a year or so, and I would just see what if anything came out of the blue.

It was the other Iran that came out of the blue, several months later. I knew instantly that a big fish had surfaced, and that I was going to land it, and soon. When I reflect more deeply on the color blue, deeper still than the image of the dome in Isfahan, I realize that what it really means for me is the sea inside: the deep, uncharted waters of one’s own interior life, where unlived desires and loves swim and wheel and turn, calling to us, at times barely audible, at other times with a clarion call, to haul them up into the light before the light goes out.

When I reflect on what is still unlived in me, travel for its own sake, or out of simple curiosity, is not the first thing to come to mind. I have spent a substantial part of my life traveling the world. Nowadays I find the place where I live to be as full of curious customs and enchantments as anywhere. But then, those romanticized images of Iran from my youth had never dissolved, even if they had fallen below the surface; their lingering presence still exerted a magnetic pull that had now emerged in the form of words. Again my response wasn’t so much a decision as a realization, a strange elation at the dawning upon me of what was next: Oh! And now this! I felt, walking through those redwoods in Marin County, which is so beautiful there is surely no need to go anywhere: I am going to Iran! Of course! The power of adventure was upon me again.

As soon as those three words swooped into my mind, I knew the subject was far bigger in scope than my own personal curiosities and subjective story. In recent years Iran has been more at the forefront of people’s minds than almost any other country. It is never far from the front pages today, so that phrase, the other Iran, arose not only from my personal unconscious, but from the broader context of the current climate. Ever since the hostage crisis of 1979, America’s relations with Iran have been strained at best and dangerous at worst. But then it became the crux of the Axis of Evil, as George W. Bush proclaimed to the world. The mullahs, we were told, ran a quasi-fascist state full of terrorists that was on the verge of going nuclear, and that would be the ruin of all of us. With all the help from Ahmadinejad they could have wished for, the White House and the press succeeded in drawing a caricature of Iran that not only demonized an entire culture but dehumanized it.

The image of Iran as a dark and scary place, full of nuke-toting mullahs, remains a difficult one to dislodge from the collective imagination. And, especially in the light of Ahmadinejad’s tirades and intransigence, with good reason. Even more so, since, in June of 2009, the hopes of the Green Revolution were quashed in a stolen election and the violence that followed. And yet, paradoxically, what we also saw at that time on our screens was an Iran that so many Iranians themselves already knew their country to be: a young, vibrant, questioning, highly creative culture with dreams not so very different from our own.

This was the Iran, some six months before those fateful elections, that I wanted to bring to light—to touch and be touched by. I wanted to humanize its culture and its people in my own mind, to resist the temptation to objectify them as “other”—as a people somehow different from and inferior to us and therefore legitimate targets for our aggression; and also to help do something of the same for my readers. I wanted to look beyond the political wrangling altogether, to the truth and beauty of an ancient and sophisticated culture; to know something of life as it is lived there, beyond the slogans and the headlines; to touch the creative spirit of Iran and to be touched by it in turn.

Above all, I wanted to see if the Iran of today could give substance and value to the images I had cherished for decades. Those images—the poetry, the music, the Sufis, the soaring domes—are for me metaphors for wholeness. They have lingered through my lifetime because they represent a culture that embraced both its deepest longings and its delight in the sensuous world—a culture that in my imagination mirrored the possibility of my own synthesis of body and soul, soul and spirit. Finally, they represent a creative genius that has resulted in works of unparalleled beauty.

For my traveling companion I would take along Rumi, guide of souls. Rumi, the thirteenth-century Iranian poet I had been consulting for years—the one whose family had fled Iran before the Mongol hordes, and whose tomb now lay in the city of Konya, in Turkey. Of all poets, Rumi spoke my own heart to me. He knew the primordial sense of home I still hankered for. He knew the loss of it and also the union with it. He called it the “Beloved”; and he sang its praises as no one else has.

So, with Rumi in my pocket, I would set off to discover if the world I imagined was a current reality in Iran today, or merely a chimera of my own making; and if it did exist, whether it might still shine a light on the hidden truths of my own inner world. All this happened and more—more than I ever bargained for.

A couple of months after that walk in the redwoods, I was on a Lufthansa flight to Tehran.

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1 Writing Iran

CHAPTER 2 Leaving the Known

CHAPTER 3 Paradise and Poetry

CHAPTER 4 Talking Stones

CHAPTER 5 Return to the Source

CHAPTER 6 The Blue Dome

CHAPTER 7 Drink the Wine

CHAPTER 8 More Than One Veil

CHAPTER 9 Christmas in Tehran

CHAPTER 10 One Imam and Three Wise Men

CHAPTER 11 The Sorrow in Shiraz

CHAPTER 12 Razor’s Edge

CHAPTER 13 Politics as Usual

CHAPTER 14 In Mesopotamia

CHAPTER 15 Return to Beauty

CHAPTER 16 Interrogation, with Room Service

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHAPTER 1 Writing Iran

CHAPTER 2 Leaving the Known

CHAPTER 3 Paradise and Poetry

CHAPTER 4 Talking Stones

CHAPTER 5 Return to the Source

CHAPTER 6 The Blue Dome

CHAPTER 7 Drink the Wine

CHAPTER 8 More Than One Veil

CHAPTER 9 Christmas in Tehran

CHAPTER 10 One Imam and Three Wise Men

CHAPTER 11 The Sorrow in Shiraz

CHAPTER 12 Razor’s Edge

CHAPTER 13 Politics as Usual

CHAPTER 14 In Mesopotamia

CHAPTER 15 Return to Beauty

CHAPTER 16 Interrogation, with Room Service

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS