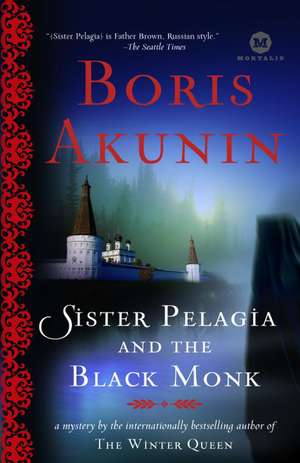

Sister Pelagia and the Black Monk: Mortalis

Autor Boris Akunin Traducere de Andrew Bromfielden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2008

Fans of Sister Pelagia and the White Bulldog, the first book in Akunin’s Pelagia trilogy, will be instantly mesmerized–and frightened–by this latest foray into Zavolzhsk’s spiritual underworld.

Praise:

“For all his status as a globe-circling bestseller, Akunin keeps faith in his sleekly engineered and allusive whodunnits with the classical virtues of Russian prose. . . . That polish lends his books a peculiar charm.”

–The Independent (London)

“Readers can hear echoes of Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Anton Chekov in whodunits that, because of their literary overtones, can be guiltlessly consumed as entertainment.”

–Los Angeles Times

Preț: 103.27 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 155

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.76€ • 20.69$ • 16.35£

19.76€ • 20.69$ • 16.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812975147

ISBN-10: 0812975146

Pagini: 356

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Seria Mortalis

ISBN-10: 0812975146

Pagini: 356

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Seria Mortalis

Notă biografică

BORIS AKUNIN is the pen name of Grigory Chkhartishvili, who was born in the Republic of Georgia in 1956. A philologist, critic, essayist, and translator of Japanese, Akunin published his first detective stories in 1998 and has already become one of the most widely read authors in Russia.

He is the author of eleven Erast Fandorin novels, including The Winter Queen, The Turkish Gambit, Murder on the Leviathan, The Death of Achilles, and Special Assignments, available from Random House Trade Paperbacks; and Sister Pelagia and the White Bulldog and Sister Pelagia and the Black Monk, in the Sister Pelagia series. He lives in Moscow.

He is the author of eleven Erast Fandorin novels, including The Winter Queen, The Turkish Gambit, Murder on the Leviathan, The Death of Achilles, and Special Assignments, available from Random House Trade Paperbacks; and Sister Pelagia and the White Bulldog and Sister Pelagia and the Black Monk, in the Sister Pelagia series. He lives in Moscow.

Extras

PART ONE

The Canaan Expeditions

The First Expedition

The Adventures of the Comic

Alexei Stepanovich’s preparations did not take long and he left on his secret expedition two days after the conversation with His Grace, after having received strict instructions to send reports on his progress at least once every three days.

Taking into account the wait for the steamer in Sineozersk and the subsequent voyage across the lake, the journey to New Ararat took four days, and the first letter arrived after exactly one week; in other words it appeared that for all his nihilistic attitude, Alyosha was a reliable envoy who carried out his instructions to the letter.

His Grace was very pleased with the report’s punctual arrival and the report itself, but pleased most of all because he had not been mistaken in the boy. He summoned Berdichevsky and Sister Pelagia and read out the report to them, although he occasionally frowned at the insufferably rollicking freedom of the style.

Alexei Stepanovich’s First Letter

To Roland’s most glorious Archbishop Turpin from his faithful paladin, sent to do battle with enchanters and Saracens,

Oh pastor of great wisdom and sternness,

Terror of deep-rooted superstitions,

Luminary of faith and loving-kindness,

Defender of orphans and lash of the proud!

At your feet do I humbly cast down

My simple and artless tale.

Ah-oo!

As, shaking on a creaking wagon,

I struggled through the kingdom of Zavolzhsk,

And on that mournful road did count

Fifteen thousand, one hundred and one

Ruts and also potholes deep,

Many a time there came to me

Bad thoughts about Your Grace’s person

And I did utter sacrilegious words.

Ah-oo!

But when the Blue Sea’s sacred waters

Did glitter brightly in the distance far,

Conquered by this captivating landscape,

Straightaway did I forget my hardships,

And prayed as I was borne across

On the smoke-puffing, snow white vessel

Named for the good Saint Basilisk.

Ah-oo!

Through the long, moonlit, chilly night

I shivered ’neath my meager blanket

And when I tried to close my eyes in sleep,

My fragile dreams were forthwith interrupted

By the captain’s wild swearing rant,

The devout chanting of the sailors’ prayers,

And the bell’s booming hourly chime.

And so, to switch from exhausting versification to delightfully welcome prose, I disembarked on the quayside in New Ararat short of sleep and as bad-tempered as the devil. Oh, forgive me, Father—it just slipped out, and if I cross it out now, it will look untidy, and you don’t like that, so to hell with the devil, let him be.

To tell the truth, in addition to the sounds of the ship, I was also prevented from sleeping by the book that you placed in my basket, together with the incomparable episcopal curd rolls, as you saw me off, adding in a most innocent voice, “Pay no attention to the title, Alyosha, and don’t worry, it’s not religious reading, just a little novel—to help you pass the time on the journey.” Oh most perfidious of the priests of Babylon!

The title—The Possessed—and the substantial thickness of the “little novel” really did frighten me at first, and I only started reading it on the steamer, to the sound of the waves splashing and the seagulls calling. In one night I read it halfway through, and I think I have understood why you slipped me this inarticulate but inspired treatise masquerading as belles lettres. Not, of course, because of that senseless rogue Petrusha Verkhovensky and those caricatured Carbonari who are his comrades, but for the sake of Stavrogin, in whose example you no doubt perceive my own fatal danger: to play the Übermensch and end up as a buffoon or, in your terminology, “to doom my immortal soul.”

A shot wide of the mark, Eminence. There is a fundamental difference between the Byronic Mr. Stavrogin and me. He acts outrageously because he believes in god (I can just see how you have wrinkled up your brow at this point—very well then, let it be “in God”) and he feels offended with Him: Why will You not turn Your paternal gaze on a naughty child like me, why do You not rebuke me or crush me under Your foot? Hey there! Where are You? Wake up! Or else I might start imagining You don’t even exist. Stavrogin is bored with the company of ordinary people; what he wants is the supreme Interlocutor. But, unlike Dostoyevsky’s defiler of little girls and seducer of idiots, I do not believe either in God or god, and that is my firm position. Human company is quite sufficient for me.

Your earlier literary hint was closer to the mark, when you made me a present of Count Tolstoy’s composition War and Peace for my saint’s day. I am more like Bolkonsky—not, of course, in terms of his lordliness, but in sharing an interest in Bonapartism. I am twenty-four now, and there is still no sign of my Toulon; in fact there is not even a distant prospect of it. Tolstoy’s prince developed such exorbitant vanity owing to his full belly and blasé attitude, for, after all, Fortune had simply given him every imaginable sweet morsel in her possession—noble status, wealth, beauty—all by right of birth, so that he had nothing else left to wish for except to become the people’s idol. But I, by contrast, come from the estate of the half-starved and envious, which, by the way, makes me much more like Napoleon than Tolstoy’s aristocrat is and improves my chances of an emperor’s crown. But, joking aside, it is more difficult for a man with a full belly to scramble up to the height of a Bonaparte than for a hungry man, because a full belly inclines a man not to nimble climbing, but to philosophizing and peaceful dreaming.

But I have gotten carried away. What you expect from me is not lofty verbiage about literature, but a spy’s report about your patrimonial estate that has been engulfed in turmoil and discord.

Let me hasten to reassure Your Reverence. As is usually the case, the seat of the trouble appears far more frightening from a distance than from close up. Sitting in Zavolzhsk, one might imagine that in New Ararat everyone talks of nothing but the Black Monk and the normal flow of life has been totally mesmerized.

Nothing of the sort. Life here pulsates and gurgles in livelier fashion than in your provincial capital, and so far I have not heard any gossip at all about your Saint Dracula, that is, entschuldigen, Saint Basilisk.

At first I found New Ararat disappointing, since on the morning of my arrival the lake was covered by low clouds, which were pouring a repulsive cold rain down onto the islands, and the landscape I saw from the deck of the steamship was all wet mouse color: slimy gray bell towers with a terrible resemblance to enema tubes and the dejected roofs of the small town.

Mindful of the fact that all my expenses will be paid out of your abundant treasure houses, I ordered the porter to take me to the very best local hotel, which bears the proud name of Noah’s Ark. I had been expecting to see some kind of gloomy log structure dimly lit with icon lamps, but I was pleasantly surprised. The hotel is fitted out in a perfectly European fashion: the room has a bathroom, mirrors, and molding on the ceiling.

The majority of the guests consists of gentlewomen already of a platonic age from St. Petersburg and Moscow, but in the evening, in the coffee shop on the ground floor, I saw a veritable Princess Lointaine such as is not to be found in quiet Zavolzhsk. I do not know if the like has ever happened before in the global history of relations between the sexes, but I fell in love with the beautiful stranger on the spot, from behind, even before she turned around. Picture to yourself, my pious pastor, a slim figure in an exquisite dress of black silk and a wide-brimmed hat with ostrich feathers, and delicate, supple neck, quite blinding in its perfection, looking like a tapering alabaster column.

Sensing my gaze, the Princess turned to present me with her profile, which I could not make out clearly, since her majesty’s face was half-covered with a hazy veil, but what I did see was enough: a slim nose with the very slightest of aquiline curves, eyes with a moist glint . . . You are familiar with that female peculiarity (ah, but yes, how could you be, with your celibate status!) of surveying an extremely broad sector of the immediate vicinity with the edge of their vision without actually turning around very far. A man would have to twist around his entire neck and his shoulders, but a charming creature such as this one merely turns her eye a little to the side and sees everything she needs in an instant.

I am sure that the Princess made out all the details of my modest (oh, very well—let it be immodest) person. And, note, she did not turn away immediately, but first gently touched her throat and only then turned the regal back of her head to me once again. Oh, how much that gesture means, that spontaneous raising of the fingers to the source of the breath!

Ah, yes, I forgot to mention that the beauty was sitting in the coffee shop alone—you must admit that this is not entirely usual, and it intrigued me too. She might possibly have been waiting for someone, or perhaps she was simply looking out the window at the square. Inspired by those fingers, my secret allies, I bent all my mathematical abilities to solving the problem of how best to strike up an acquaintance with this Circe of New Ararat, but I had no time to complete the integral calculation. She rose abruptly to her feet, dropped a silver coin on the table, and walked out quickly, casting another swift, coal black glance at me from behind her half veil. The waiter told me that this lady often comes to the coffee shop. That means I will have another chance, I thought, and for lack of other employment I began imagining all sorts of seductive scenes, about which you, as a man of the church, do not need to know.

I had better share with you my impressions of the island.

Well, this is a really strange place to which you have sent me, Rabbi. The central square, on which the hotel stands, seems to have been cut out of some Baden-Baden or other with a pair of scissors: brightly painted stone houses two or three stories high, clean people strolling about everywhere, almost as bright in the evening as it is during the day. And everywhere there are establishments that could hardly be more worldly—I would even call them vain in the biblical sense—with quite incredible names: a restaurant serving meat in abundance called Balthasar’s Feast, a hairdresser’s called Delilah, a souvenir shop called Gifts of the Magi, a bank called The Widow’s Mite, and more in the same vein. But only a few minutes’ walk away from the square you find yourself transported to the banks of the Neva shortly after the foundation of our consumptive capital, in 1704: workers running about with wheelbarrows, hammering stakes into the swampy ground, sawing logs, digging pits. All with beards and black cassocks, but with their sleeves rolled up and wearing oilcloth aprons—the veritable realization of the revolutionary dream of making the parasitical estate of clerics perform socially useful work.

Several times a day, in the most unexpected places, you come across the lord and master of this entire ant army, the archimandrite Vitalii II (sic!), who really does look like Peter the Great: long and lanky, menacing, impetuous, striding along so vigorously that his cassock balloons up around him and his retinue can hardly keep up behind. Not a priest, but a cannonball, blasted from a cannon. I would love to set you, Monk Peresvet of Kulikovo, against him one to one, and see who would come off best. I would probably bet on you anyway—the archimandrite may be more rapid-firing, but your caliber is heavier.

Here on the islands they seem to have mastered the art, previously unheard of in Russia, of making money out of everything and even out of nothing. It is usually entirely the other way around here: the more gold ore or diamonds there are lying around under our feet, the more ruinous the losses. But here, no sooner did Vitalii decide to put the useless stony ground on the Cape of Righteousness to good use than it was discovered that the stones there are not ordinary, but holy, for they were watered with the blood of the holy martyrs who were put to the sword three hundred years ago by the cutthroats of the Swedish Count De la Gardie. The stones really do have a reddish-brownish color, only I suspect it is not from blood, but because they are impregnated with iron oxide. But then, that is not important; what is important is that now the pilgrims themselves chip pieces off the boulders and carry them away. There is a special monk standing there with a mattock and a pair of scales. If you want to use the mattock, pay fifteen kopecks. If you want to take the sacred stone away with you, weigh it and take it—it costs ninety-nine kopecks a pound. And so Vitalii’s useless plot of land is gradually cleared, and the monastery coffers profit in the process. What a splendid arrangement!

Or take the water. An entire regiment of monks pours the local well water into bottles, seals the bottles with caps, and glues on labels that say NEW ARARAT HOLY WATER, BLESSED BY THE REVEREND FATHER VITALII, after which this H2O is shipped wholesale to the mainland—to Peter and especially to devout Moscow. Meanwhile, in Ararat, for the convenience of the pilgrims, they have constructed a wonder of wonders, a miracle of miracles: the Automatic Holy Water Dispensers. These cunning machines, the invention of local Kulibins, are located in a wooden pavilion. When someone drops a five-kopeck coin into the slot, it falls on a valve, a shutter opens, and the holy water pours out into a mug. There is also a more expensive version, for ten kopecks, in which raspberry syrup is added to the water in a kind of special “triple blessing.” They say that in summer there is a queue for this place, but I have come at a bad time—from mid-autumn the pavilion is closed so that this cunning technology will not be damaged by the night frosts. But never mind; sooner or later Vitalii will come up with the idea of installing a steam generator inside the dispensers to warm them, and then they will bring forth fruit in winter too.

The Canaan Expeditions

The First Expedition

The Adventures of the Comic

Alexei Stepanovich’s preparations did not take long and he left on his secret expedition two days after the conversation with His Grace, after having received strict instructions to send reports on his progress at least once every three days.

Taking into account the wait for the steamer in Sineozersk and the subsequent voyage across the lake, the journey to New Ararat took four days, and the first letter arrived after exactly one week; in other words it appeared that for all his nihilistic attitude, Alyosha was a reliable envoy who carried out his instructions to the letter.

His Grace was very pleased with the report’s punctual arrival and the report itself, but pleased most of all because he had not been mistaken in the boy. He summoned Berdichevsky and Sister Pelagia and read out the report to them, although he occasionally frowned at the insufferably rollicking freedom of the style.

Alexei Stepanovich’s First Letter

To Roland’s most glorious Archbishop Turpin from his faithful paladin, sent to do battle with enchanters and Saracens,

Oh pastor of great wisdom and sternness,

Terror of deep-rooted superstitions,

Luminary of faith and loving-kindness,

Defender of orphans and lash of the proud!

At your feet do I humbly cast down

My simple and artless tale.

Ah-oo!

As, shaking on a creaking wagon,

I struggled through the kingdom of Zavolzhsk,

And on that mournful road did count

Fifteen thousand, one hundred and one

Ruts and also potholes deep,

Many a time there came to me

Bad thoughts about Your Grace’s person

And I did utter sacrilegious words.

Ah-oo!

But when the Blue Sea’s sacred waters

Did glitter brightly in the distance far,

Conquered by this captivating landscape,

Straightaway did I forget my hardships,

And prayed as I was borne across

On the smoke-puffing, snow white vessel

Named for the good Saint Basilisk.

Ah-oo!

Through the long, moonlit, chilly night

I shivered ’neath my meager blanket

And when I tried to close my eyes in sleep,

My fragile dreams were forthwith interrupted

By the captain’s wild swearing rant,

The devout chanting of the sailors’ prayers,

And the bell’s booming hourly chime.

And so, to switch from exhausting versification to delightfully welcome prose, I disembarked on the quayside in New Ararat short of sleep and as bad-tempered as the devil. Oh, forgive me, Father—it just slipped out, and if I cross it out now, it will look untidy, and you don’t like that, so to hell with the devil, let him be.

To tell the truth, in addition to the sounds of the ship, I was also prevented from sleeping by the book that you placed in my basket, together with the incomparable episcopal curd rolls, as you saw me off, adding in a most innocent voice, “Pay no attention to the title, Alyosha, and don’t worry, it’s not religious reading, just a little novel—to help you pass the time on the journey.” Oh most perfidious of the priests of Babylon!

The title—The Possessed—and the substantial thickness of the “little novel” really did frighten me at first, and I only started reading it on the steamer, to the sound of the waves splashing and the seagulls calling. In one night I read it halfway through, and I think I have understood why you slipped me this inarticulate but inspired treatise masquerading as belles lettres. Not, of course, because of that senseless rogue Petrusha Verkhovensky and those caricatured Carbonari who are his comrades, but for the sake of Stavrogin, in whose example you no doubt perceive my own fatal danger: to play the Übermensch and end up as a buffoon or, in your terminology, “to doom my immortal soul.”

A shot wide of the mark, Eminence. There is a fundamental difference between the Byronic Mr. Stavrogin and me. He acts outrageously because he believes in god (I can just see how you have wrinkled up your brow at this point—very well then, let it be “in God”) and he feels offended with Him: Why will You not turn Your paternal gaze on a naughty child like me, why do You not rebuke me or crush me under Your foot? Hey there! Where are You? Wake up! Or else I might start imagining You don’t even exist. Stavrogin is bored with the company of ordinary people; what he wants is the supreme Interlocutor. But, unlike Dostoyevsky’s defiler of little girls and seducer of idiots, I do not believe either in God or god, and that is my firm position. Human company is quite sufficient for me.

Your earlier literary hint was closer to the mark, when you made me a present of Count Tolstoy’s composition War and Peace for my saint’s day. I am more like Bolkonsky—not, of course, in terms of his lordliness, but in sharing an interest in Bonapartism. I am twenty-four now, and there is still no sign of my Toulon; in fact there is not even a distant prospect of it. Tolstoy’s prince developed such exorbitant vanity owing to his full belly and blasé attitude, for, after all, Fortune had simply given him every imaginable sweet morsel in her possession—noble status, wealth, beauty—all by right of birth, so that he had nothing else left to wish for except to become the people’s idol. But I, by contrast, come from the estate of the half-starved and envious, which, by the way, makes me much more like Napoleon than Tolstoy’s aristocrat is and improves my chances of an emperor’s crown. But, joking aside, it is more difficult for a man with a full belly to scramble up to the height of a Bonaparte than for a hungry man, because a full belly inclines a man not to nimble climbing, but to philosophizing and peaceful dreaming.

But I have gotten carried away. What you expect from me is not lofty verbiage about literature, but a spy’s report about your patrimonial estate that has been engulfed in turmoil and discord.

Let me hasten to reassure Your Reverence. As is usually the case, the seat of the trouble appears far more frightening from a distance than from close up. Sitting in Zavolzhsk, one might imagine that in New Ararat everyone talks of nothing but the Black Monk and the normal flow of life has been totally mesmerized.

Nothing of the sort. Life here pulsates and gurgles in livelier fashion than in your provincial capital, and so far I have not heard any gossip at all about your Saint Dracula, that is, entschuldigen, Saint Basilisk.

At first I found New Ararat disappointing, since on the morning of my arrival the lake was covered by low clouds, which were pouring a repulsive cold rain down onto the islands, and the landscape I saw from the deck of the steamship was all wet mouse color: slimy gray bell towers with a terrible resemblance to enema tubes and the dejected roofs of the small town.

Mindful of the fact that all my expenses will be paid out of your abundant treasure houses, I ordered the porter to take me to the very best local hotel, which bears the proud name of Noah’s Ark. I had been expecting to see some kind of gloomy log structure dimly lit with icon lamps, but I was pleasantly surprised. The hotel is fitted out in a perfectly European fashion: the room has a bathroom, mirrors, and molding on the ceiling.

The majority of the guests consists of gentlewomen already of a platonic age from St. Petersburg and Moscow, but in the evening, in the coffee shop on the ground floor, I saw a veritable Princess Lointaine such as is not to be found in quiet Zavolzhsk. I do not know if the like has ever happened before in the global history of relations between the sexes, but I fell in love with the beautiful stranger on the spot, from behind, even before she turned around. Picture to yourself, my pious pastor, a slim figure in an exquisite dress of black silk and a wide-brimmed hat with ostrich feathers, and delicate, supple neck, quite blinding in its perfection, looking like a tapering alabaster column.

Sensing my gaze, the Princess turned to present me with her profile, which I could not make out clearly, since her majesty’s face was half-covered with a hazy veil, but what I did see was enough: a slim nose with the very slightest of aquiline curves, eyes with a moist glint . . . You are familiar with that female peculiarity (ah, but yes, how could you be, with your celibate status!) of surveying an extremely broad sector of the immediate vicinity with the edge of their vision without actually turning around very far. A man would have to twist around his entire neck and his shoulders, but a charming creature such as this one merely turns her eye a little to the side and sees everything she needs in an instant.

I am sure that the Princess made out all the details of my modest (oh, very well—let it be immodest) person. And, note, she did not turn away immediately, but first gently touched her throat and only then turned the regal back of her head to me once again. Oh, how much that gesture means, that spontaneous raising of the fingers to the source of the breath!

Ah, yes, I forgot to mention that the beauty was sitting in the coffee shop alone—you must admit that this is not entirely usual, and it intrigued me too. She might possibly have been waiting for someone, or perhaps she was simply looking out the window at the square. Inspired by those fingers, my secret allies, I bent all my mathematical abilities to solving the problem of how best to strike up an acquaintance with this Circe of New Ararat, but I had no time to complete the integral calculation. She rose abruptly to her feet, dropped a silver coin on the table, and walked out quickly, casting another swift, coal black glance at me from behind her half veil. The waiter told me that this lady often comes to the coffee shop. That means I will have another chance, I thought, and for lack of other employment I began imagining all sorts of seductive scenes, about which you, as a man of the church, do not need to know.

I had better share with you my impressions of the island.

Well, this is a really strange place to which you have sent me, Rabbi. The central square, on which the hotel stands, seems to have been cut out of some Baden-Baden or other with a pair of scissors: brightly painted stone houses two or three stories high, clean people strolling about everywhere, almost as bright in the evening as it is during the day. And everywhere there are establishments that could hardly be more worldly—I would even call them vain in the biblical sense—with quite incredible names: a restaurant serving meat in abundance called Balthasar’s Feast, a hairdresser’s called Delilah, a souvenir shop called Gifts of the Magi, a bank called The Widow’s Mite, and more in the same vein. But only a few minutes’ walk away from the square you find yourself transported to the banks of the Neva shortly after the foundation of our consumptive capital, in 1704: workers running about with wheelbarrows, hammering stakes into the swampy ground, sawing logs, digging pits. All with beards and black cassocks, but with their sleeves rolled up and wearing oilcloth aprons—the veritable realization of the revolutionary dream of making the parasitical estate of clerics perform socially useful work.

Several times a day, in the most unexpected places, you come across the lord and master of this entire ant army, the archimandrite Vitalii II (sic!), who really does look like Peter the Great: long and lanky, menacing, impetuous, striding along so vigorously that his cassock balloons up around him and his retinue can hardly keep up behind. Not a priest, but a cannonball, blasted from a cannon. I would love to set you, Monk Peresvet of Kulikovo, against him one to one, and see who would come off best. I would probably bet on you anyway—the archimandrite may be more rapid-firing, but your caliber is heavier.

Here on the islands they seem to have mastered the art, previously unheard of in Russia, of making money out of everything and even out of nothing. It is usually entirely the other way around here: the more gold ore or diamonds there are lying around under our feet, the more ruinous the losses. But here, no sooner did Vitalii decide to put the useless stony ground on the Cape of Righteousness to good use than it was discovered that the stones there are not ordinary, but holy, for they were watered with the blood of the holy martyrs who were put to the sword three hundred years ago by the cutthroats of the Swedish Count De la Gardie. The stones really do have a reddish-brownish color, only I suspect it is not from blood, but because they are impregnated with iron oxide. But then, that is not important; what is important is that now the pilgrims themselves chip pieces off the boulders and carry them away. There is a special monk standing there with a mattock and a pair of scales. If you want to use the mattock, pay fifteen kopecks. If you want to take the sacred stone away with you, weigh it and take it—it costs ninety-nine kopecks a pound. And so Vitalii’s useless plot of land is gradually cleared, and the monastery coffers profit in the process. What a splendid arrangement!

Or take the water. An entire regiment of monks pours the local well water into bottles, seals the bottles with caps, and glues on labels that say NEW ARARAT HOLY WATER, BLESSED BY THE REVEREND FATHER VITALII, after which this H2O is shipped wholesale to the mainland—to Peter and especially to devout Moscow. Meanwhile, in Ararat, for the convenience of the pilgrims, they have constructed a wonder of wonders, a miracle of miracles: the Automatic Holy Water Dispensers. These cunning machines, the invention of local Kulibins, are located in a wooden pavilion. When someone drops a five-kopeck coin into the slot, it falls on a valve, a shutter opens, and the holy water pours out into a mug. There is also a more expensive version, for ten kopecks, in which raspberry syrup is added to the water in a kind of special “triple blessing.” They say that in summer there is a queue for this place, but I have come at a bad time—from mid-autumn the pavilion is closed so that this cunning technology will not be damaged by the night frosts. But never mind; sooner or later Vitalii will come up with the idea of installing a steam generator inside the dispensers to warm them, and then they will bring forth fruit in winter too.

Descriere

This follow-up to the first book in Akunin's Pelagia trilogy, "Sister Pelagia and the White Bulldog," is a mesmerizing--and frightening--foray into Zavolzhsk's spiritual underworld.