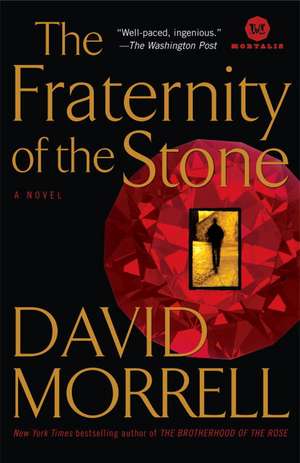

The Fraternity of the Stone: Mortalis

Autor David Morrellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

In this novel of thrilling suspense, a former killer is drawn back into that electrifying world where no one is as he seems–and where life’s most horrifying, harrowing game is played.

Preț: 112.23 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.48€ • 22.34$ • 17.73£

21.48€ • 22.34$ • 17.73£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 14-28 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345514509

ISBN-10: 0345514505

Pagini: 480

Dimensiuni: 134 x 208 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Mortalis

ISBN-10: 0345514505

Pagini: 480

Dimensiuni: 134 x 208 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Mortalis

Notă biografică

David Morrell is the award-winning author of First Blood—the novel in which Rambo was created—as well as twenty-seven other books. This book was the basis for the 1989 mini-series starring Robert Mitchum. With eighteen million copies in print, his work has been translated into twenty-six languages. He was a professor in the English department at the University of Iowa and currently serves as the copresident of the International Thriller Writers organization. He lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, with his wife.

Extras

The House of the Dead

Chapter One

It was north of Quentin, Vermont. You could see it partly hidden by fir trees a quarter mile off the two-lane blacktop, to the right on the crest of a hill. Beyond it loomed a higher hill, thick with maple trees, brilliant now in the autumn, vivid orange and yellow and red. A high wire fence ran parallel to the blacktop, the sides veering off at right angles, disappearing back into the forest. You’d have trouble calculating, since you couldn’t see how far back the fences went, but you wouldn’t be wrong to guess that the property covered at least a hundred acres. The nearest building—apart from the one on the hill—was a boarded-up service station quite a ways behind you, out of sight, on the other side of the corkscrew turn that led to this straightaway. And you wouldn’t get to the maple syrup factory up ahead for more than a mile.

Remote. Secluded.

Peaceful.

Glancing toward the pine tree-studded hill, you might suspect that the partly hidden structure, with its gleaming wood, was a millionaire’s retreat, a forest hideaway where the pressures of business could be relieved by who could imagine what distractions.

Or possibly the building was a ski resort, closed till the snow fell. Or . . .

But from just driving by, of course, you could never know. There was neither a mailbox nor a sign at the gate, and the gate itself had a thick chain holding it in place—an even thicker lock. The lane on the other side was weedgrown, squeezed by bushes and drooping pines. To be sure, you could always ask at the maple syrup factory if your curiosity lasted till then, but you’d only feel more frustrated as a result. The workers there, true New Englanders, were willing to talk to strangers about the weather but not about their own or their neighbor’s business. It wouldn’t have mattered, anyhow. They didn’t know, either, though there were rumors.

Chapter Two

From the air, the structure on the hill was larger than the view from the road suggested. Indeed, an elevated vantage point revealed that the building wasn’t alone. Smaller buildings—otherwise hidden by pine trees—formed three sides of a square, the fourth of which was the lodge itself. Enclosed by the square was a lawn. Two white-stone walkways intersected at its middle, bordered by flower gardens, trees, and shrubs. The effect was one of balance and order, symmetry, proportion. Soothing. Even the smaller buildings, though joined like rows of townhouses, had small peaked roofs in imitation of the larger peaked roof on the lodge.

Despite the expanse of the estate, however, remarkably few people showed themselves down there. The tiny figure of a groundskeeper tended the lawn. Two miniature workmen harvested apples from an orchard outside one line of buildings. A wisp of smoke rose from a bonfire in a considerable vegetable garden flanking the opposite line of buildings. With so sizable a commitment to agriculture, the estate presumably had many residents, yet except for those few signs of life, the place seemed deserted. If there were guests, it hardly seemed natural for them to ignore the pleasure of this bright crisp autumn day. To remain indoors, they must surely have an important reason.

But then the seclusion of the inhabitants was part of the mystery about this place. Since 1951, when teams of construction workers had arrived from somewhere—not from the local town, though whoever was funding the project at least had the goodness to buy a decent amount of supplies from there—the citizens of Quentin had wondered what was happening on that hill. When the workers put up the gate and departed, the local busybodies noted a fascinating pattern. They recalled stories they’d recently read about the development of the atomic bomb in New Mexico at the end of the war. The government had built a small town on a mountain there, it was said. The local communities had therefore hoped for an increase in business; but they’d waited in vain, for the strange thing was that people went onto that mountain, but—as with the estate on this hill—they didn’t come down.

Chapter Three

The unit, one of twenty in the complex, each the same, consisted of two levels. On the bottom, a workroom contained whatever equipment its occupant had chosen to use to pass his leisure time. In other parts of the complex, some perhaps painted or sculpted or wove, possibly worked with wood and carpentry tools. Or, since each unit had a small private garden enclosed by a wall, adjacent to the workroom, some might practice horticulture, perhaps growing roses.

In the present case, the occupant had chosen exercise and composition. He knew that he couldn’t concentrate if his body was not in condition. Indeed, in his former life he’d been intensely devoted to the principles of Zen, aware that exercise itself was spiritual. Each day for an hour he lifted weights, skipped rope, performed calisthenics, and rehearsed the katas or dance steps of the Oriental martial arts. He did all this with humility, taking no satisfaction in the perfection of his physique, for he realized that his body was but an instrument of his soul. In fact, the effect of his daily workouts had little obvious result. His torso was lean, ascetic, low on the protein his muscles required to replace the tissue his exercise wore down. He ate no meat. On Friday, he took only bread and water. Some days, he ate nothing. But his discipline gave him strength.

His compositions fulfilled another purpose. During his early months here, he’d been tempted to write about his motive for coming, to purge himself, to vent his anguish. But his need to forget was greater. To relieve the pressure of his urge for self-expression, he’d written haikus first, an understandable choice given his sympathy with Zen. He selected topics with no relevance to what disturbed him—the song of a bird, the breath of the wind. But the nature of a haiku, its complicated tension based on purity and brevity, led him to greater attempts at compression and refinement until no statement at all seemed the perfect haiku, and he stared past his pen toward the vacuum of a barren page. Compulsively, he’d switched to the sonnet form, alternating between Shakespearean and Petrarchan, each with a different rhyme scheme, both demanding a perfect organization of fourteen lines. The problem of that intricate puzzle was enough to occupy him. More interested in how he wrote than what he wrote, he expressed himself about minuscule matters and was able to forget the troubling great ones. He wrote as best he could, not out of pride, but out of respect for the puzzle. Even so, he knew that eloquence eluded him. Perhaps in another unit of this complex, an occupant had—like himself—become engaged with poetry. Perhaps that other occupant had produced such perfectly beautiful sonnets that they rivaled those of Shakespeare and Petrarch themselves.

It wouldn’t have mattered. Nothing any occupant devised—paintings, statues, tapestries, or furniture—had any value. All were insignificant. When the men who fashioned them died, they were placed on a board and buried in an unmarked grave, and the objects they left behind, their clothes, their few belongings, their sonnets, even a skipping rope, were destroyed. It would be as if they had never existed.

Chapter Four

The psychiatrist, as expected, had been a priest. He’d worn the traditional black suit and white collar, his face somewhat wrinkled, bullet-gray, as he lit a cigarette and peered at Drew from across his desk.

“You understand the gravity of your request.”

“I’ve considered it carefully.”

“You made your decision—when?”

“Three months ago.”

“And you waited . . . ?”

“Till now. To analyze the implications. Naturally I had to be sure.”

The priest inhaled from his cigarette, thoughtful, studying Drew. His name was Father Hafer. He was in his late forties, his short hair the same bullet-gray color as his face. Exhaling smoke, he made an offhanded gesture with the cigarette. “Naturally. The other side of the issue is, how can we be sure? Of your commitment? Of your determination and resolve?”

“You can’t.”

“Well, there it is then.”

“But I can, and that’s what matters. This is what I need. I’ve resigned myself.”

“To what?”

“Not ‘to.’?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“From.” Drew nodded toward the clamorous Boston street beyond the first-floor window of this rectory office.

“Everything? The world?”

Drew didn’t respond.

“Of course, that’s what the eremitical life is all about. Withdrawal,” Father Hafer said and shrugged. “Still, a negative attitude isn’t sufficient. Your motive has to be positive as well. Seeking, not merely fleeing.”

“Oh, I’m seeking all right.”

“Indeed?” The priest raised his eyebrows. “For what?”

“Salvation.”

Father Hafer considered him, exhaling smoke. “An admirable answer.” He brushed an ash from his cigarette into a metal tray. “So quick to the lips, so readily given. Have you been religious long?”

“For the past three months.”

“And before?”

Again Drew didn’t respond.

“You are a Roman Catholic?”

“I was baptized into the faith. My parents were quite religious.” Suddenly remembering how they’d died, he felt his throat ache. “We went to church often. Mass. The Stations of the Cross. I received the sacraments up through confirmation, and you know what they say about confirmation. It made me a soldier of Christ.” Drew bitterly smiled. “Oh, I believed.”

“And after that?”

“The term is ‘lapsed.”

“Have you made your Easter duty?’?”

“Not in thirteen years.”

“You understand what that means?”

“By not going to confession and communion before Easter, I in effect resigned from the faith. I’ve been unofficially excommunicated.”

“And put your soul in immortal peril.”

Chapter One

It was north of Quentin, Vermont. You could see it partly hidden by fir trees a quarter mile off the two-lane blacktop, to the right on the crest of a hill. Beyond it loomed a higher hill, thick with maple trees, brilliant now in the autumn, vivid orange and yellow and red. A high wire fence ran parallel to the blacktop, the sides veering off at right angles, disappearing back into the forest. You’d have trouble calculating, since you couldn’t see how far back the fences went, but you wouldn’t be wrong to guess that the property covered at least a hundred acres. The nearest building—apart from the one on the hill—was a boarded-up service station quite a ways behind you, out of sight, on the other side of the corkscrew turn that led to this straightaway. And you wouldn’t get to the maple syrup factory up ahead for more than a mile.

Remote. Secluded.

Peaceful.

Glancing toward the pine tree-studded hill, you might suspect that the partly hidden structure, with its gleaming wood, was a millionaire’s retreat, a forest hideaway where the pressures of business could be relieved by who could imagine what distractions.

Or possibly the building was a ski resort, closed till the snow fell. Or . . .

But from just driving by, of course, you could never know. There was neither a mailbox nor a sign at the gate, and the gate itself had a thick chain holding it in place—an even thicker lock. The lane on the other side was weedgrown, squeezed by bushes and drooping pines. To be sure, you could always ask at the maple syrup factory if your curiosity lasted till then, but you’d only feel more frustrated as a result. The workers there, true New Englanders, were willing to talk to strangers about the weather but not about their own or their neighbor’s business. It wouldn’t have mattered, anyhow. They didn’t know, either, though there were rumors.

Chapter Two

From the air, the structure on the hill was larger than the view from the road suggested. Indeed, an elevated vantage point revealed that the building wasn’t alone. Smaller buildings—otherwise hidden by pine trees—formed three sides of a square, the fourth of which was the lodge itself. Enclosed by the square was a lawn. Two white-stone walkways intersected at its middle, bordered by flower gardens, trees, and shrubs. The effect was one of balance and order, symmetry, proportion. Soothing. Even the smaller buildings, though joined like rows of townhouses, had small peaked roofs in imitation of the larger peaked roof on the lodge.

Despite the expanse of the estate, however, remarkably few people showed themselves down there. The tiny figure of a groundskeeper tended the lawn. Two miniature workmen harvested apples from an orchard outside one line of buildings. A wisp of smoke rose from a bonfire in a considerable vegetable garden flanking the opposite line of buildings. With so sizable a commitment to agriculture, the estate presumably had many residents, yet except for those few signs of life, the place seemed deserted. If there were guests, it hardly seemed natural for them to ignore the pleasure of this bright crisp autumn day. To remain indoors, they must surely have an important reason.

But then the seclusion of the inhabitants was part of the mystery about this place. Since 1951, when teams of construction workers had arrived from somewhere—not from the local town, though whoever was funding the project at least had the goodness to buy a decent amount of supplies from there—the citizens of Quentin had wondered what was happening on that hill. When the workers put up the gate and departed, the local busybodies noted a fascinating pattern. They recalled stories they’d recently read about the development of the atomic bomb in New Mexico at the end of the war. The government had built a small town on a mountain there, it was said. The local communities had therefore hoped for an increase in business; but they’d waited in vain, for the strange thing was that people went onto that mountain, but—as with the estate on this hill—they didn’t come down.

Chapter Three

The unit, one of twenty in the complex, each the same, consisted of two levels. On the bottom, a workroom contained whatever equipment its occupant had chosen to use to pass his leisure time. In other parts of the complex, some perhaps painted or sculpted or wove, possibly worked with wood and carpentry tools. Or, since each unit had a small private garden enclosed by a wall, adjacent to the workroom, some might practice horticulture, perhaps growing roses.

In the present case, the occupant had chosen exercise and composition. He knew that he couldn’t concentrate if his body was not in condition. Indeed, in his former life he’d been intensely devoted to the principles of Zen, aware that exercise itself was spiritual. Each day for an hour he lifted weights, skipped rope, performed calisthenics, and rehearsed the katas or dance steps of the Oriental martial arts. He did all this with humility, taking no satisfaction in the perfection of his physique, for he realized that his body was but an instrument of his soul. In fact, the effect of his daily workouts had little obvious result. His torso was lean, ascetic, low on the protein his muscles required to replace the tissue his exercise wore down. He ate no meat. On Friday, he took only bread and water. Some days, he ate nothing. But his discipline gave him strength.

His compositions fulfilled another purpose. During his early months here, he’d been tempted to write about his motive for coming, to purge himself, to vent his anguish. But his need to forget was greater. To relieve the pressure of his urge for self-expression, he’d written haikus first, an understandable choice given his sympathy with Zen. He selected topics with no relevance to what disturbed him—the song of a bird, the breath of the wind. But the nature of a haiku, its complicated tension based on purity and brevity, led him to greater attempts at compression and refinement until no statement at all seemed the perfect haiku, and he stared past his pen toward the vacuum of a barren page. Compulsively, he’d switched to the sonnet form, alternating between Shakespearean and Petrarchan, each with a different rhyme scheme, both demanding a perfect organization of fourteen lines. The problem of that intricate puzzle was enough to occupy him. More interested in how he wrote than what he wrote, he expressed himself about minuscule matters and was able to forget the troubling great ones. He wrote as best he could, not out of pride, but out of respect for the puzzle. Even so, he knew that eloquence eluded him. Perhaps in another unit of this complex, an occupant had—like himself—become engaged with poetry. Perhaps that other occupant had produced such perfectly beautiful sonnets that they rivaled those of Shakespeare and Petrarch themselves.

It wouldn’t have mattered. Nothing any occupant devised—paintings, statues, tapestries, or furniture—had any value. All were insignificant. When the men who fashioned them died, they were placed on a board and buried in an unmarked grave, and the objects they left behind, their clothes, their few belongings, their sonnets, even a skipping rope, were destroyed. It would be as if they had never existed.

Chapter Four

The psychiatrist, as expected, had been a priest. He’d worn the traditional black suit and white collar, his face somewhat wrinkled, bullet-gray, as he lit a cigarette and peered at Drew from across his desk.

“You understand the gravity of your request.”

“I’ve considered it carefully.”

“You made your decision—when?”

“Three months ago.”

“And you waited . . . ?”

“Till now. To analyze the implications. Naturally I had to be sure.”

The priest inhaled from his cigarette, thoughtful, studying Drew. His name was Father Hafer. He was in his late forties, his short hair the same bullet-gray color as his face. Exhaling smoke, he made an offhanded gesture with the cigarette. “Naturally. The other side of the issue is, how can we be sure? Of your commitment? Of your determination and resolve?”

“You can’t.”

“Well, there it is then.”

“But I can, and that’s what matters. This is what I need. I’ve resigned myself.”

“To what?”

“Not ‘to.’?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“From.” Drew nodded toward the clamorous Boston street beyond the first-floor window of this rectory office.

“Everything? The world?”

Drew didn’t respond.

“Of course, that’s what the eremitical life is all about. Withdrawal,” Father Hafer said and shrugged. “Still, a negative attitude isn’t sufficient. Your motive has to be positive as well. Seeking, not merely fleeing.”

“Oh, I’m seeking all right.”

“Indeed?” The priest raised his eyebrows. “For what?”

“Salvation.”

Father Hafer considered him, exhaling smoke. “An admirable answer.” He brushed an ash from his cigarette into a metal tray. “So quick to the lips, so readily given. Have you been religious long?”

“For the past three months.”

“And before?”

Again Drew didn’t respond.

“You are a Roman Catholic?”

“I was baptized into the faith. My parents were quite religious.” Suddenly remembering how they’d died, he felt his throat ache. “We went to church often. Mass. The Stations of the Cross. I received the sacraments up through confirmation, and you know what they say about confirmation. It made me a soldier of Christ.” Drew bitterly smiled. “Oh, I believed.”

“And after that?”

“The term is ‘lapsed.”

“Have you made your Easter duty?’?”

“Not in thirteen years.”

“You understand what that means?”

“By not going to confession and communion before Easter, I in effect resigned from the faith. I’ve been unofficially excommunicated.”

“And put your soul in immortal peril.”

Recenzii

“[David] Morrell (best known for First Blood) returns to his favorite revenge theme in [this] thriller, which focuses on a hit man who renounces violence only to be flushed out of his monastic retreat back to the counterterrorist circuit.”—Kirkus Reviews

“Those who appreciate a good spy novel are going to have to clear more space on the shelf. David Morrell’s Fraternity of the Stone . . . establishes Morrell as a force to be reckoned with. . . . The plot works marvelously and should not be missed by anyone who enjoys a good spy thriller.”—Sunday News (Ridgewood, N.J.)

“Those who appreciate a good spy novel are going to have to clear more space on the shelf. David Morrell’s Fraternity of the Stone . . . establishes Morrell as a force to be reckoned with. . . . The plot works marvelously and should not be missed by anyone who enjoys a good spy thriller.”—Sunday News (Ridgewood, N.J.)

Descriere

Drew Maclane had been a star agent--until the day the killing had to stop. He had withdrawn and for six years lived the life of a hermit in a monastery. But someone has tracked him down, leaving a trail of corpses. Someone who knows how to draw him back into that electrifying world where no one is as he seems.