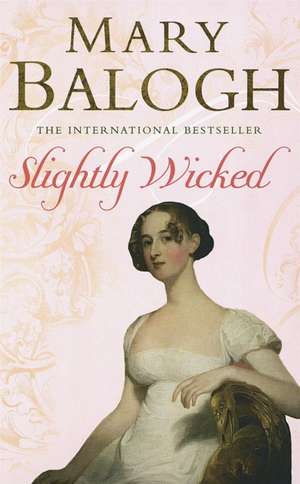

Slightly Wicked: Bedwyn Series

Autor Mary Baloghen Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 mar 2007

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 49.38 lei 3-5 săpt. | +25.85 lei 6-12 zile |

| Little Brown Book Group – 8 mar 2007 | 49.38 lei 3-5 săpt. | +25.85 lei 6-12 zile |

| dell – 31 mar 2003 | 51.75 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 49.38 lei

Preț vechi: 64.08 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 74

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.45€ • 10.10$ • 7.88£

9.45€ • 10.10$ • 7.88£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Livrare express 12-18 martie pentru 35.84 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780749937546

ISBN-10: 0749937548

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Little Brown Book Group

Seria Bedwyn Series

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0749937548

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Little Brown Book Group

Seria Bedwyn Series

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Mary Balogh is a NEW YORK TIMES bestselling author. A former teacher, she grew up in Wales and now lives in Canada.

Extras

Chapter One

Moments before the stagecoach overturned, Judith Law was deeply immersed in a daydream that had effectively obliterated the unpleasant nature of the present reality.

For the first time in her twenty-two years of existence she was traveling by stagecoach. Within the first mile or two she had been disabused of any notion she might ever have entertained that it was a romantic, adventurous mode of travel. She was squashed between a woman whose girth required a seat and a half of space and a thin, restless man who was all sharp angles and elbows and was constantly squirming to find a more comfortable position, digging her in uncomfortable and sometimes embarrassing places as he did so. A portly man opposite snored constantly, adding considerably to all the other noises of travel. The woman next to him talked unceasingly to anyone unfortunate or unwise enough to make eye contact with her, relating the sorry story of her life in a tone of whining complaint. From the quiet man on the other side of her wafted the odors of uncleanness mingled with onions and garlic. The coach rattled and vibrated and jarred over every stone and pothole in its path, or so it seemed to Judith.

Yet for all the discomforts of the road, she was not eager to complete the journey. She had just left behind the lifelong familiarity of Beaconsfield and home and family and did not expect to return to them for a long time, if ever. She was on her way to live at her Aunt Effingham's. Life as she had always known it had just ended. Though nothing had been stated explicitly in the letter her aunt had written to Papa, it had been perfectly clear to Judith that she was not going to be an honored, pampered guest at Harewood Grange, but rather a poor relation, expected to earn her keep in whatever manner her aunt and uncle and cousins and grandmother deemed appropriate. Starkly stated, she could expect only dreariness and drudgery ahead--no beaux, no marriage, no home and family of her own. She was about to become one of those shadowy, fading females with whom society abounded, dependent upon their relatives, unpaid servants to them.

It had been extraordinarily kind of Aunt Effingham to invite her, Papa had said--except that her aunt, her father's sister, who had made an extremely advantageous marriage to the wealthy, widowed Sir George Effingham when she was already past the first bloom of youth, was not renowned for kindness.

And it was all because of Branwell, the fiend, who deserved to be shot and then hanged, drawn, and quartered for his thoughtless extravagances--Judith had not had a kind thought to spare for her younger brother in many weeks. And it was because she was the second daughter, the one without any comforting label to make her continued presence at home indispensable. She was not the eldest--Cassandra was a year older than she. She was certainly not the beauty--her younger sister Pamela was that. And she was not the baby--seventeen-year-old Hilary had that dubious distinction. Judith was the embarrassingly awkward one, the ugly one, the always cheerful one, the dreamer.

Judith was the one everyone had turned and looked at when Papa came to the sitting room and read Aunt Effingham's letter aloud. Papa had fallen into severe financial straits and must have written to his sister to ask for just the help she was offering. They all knew what it would mean to the one chosen to go to Harewood. Judith had volunteered. They had all cried when she spoke up, and her sisters had all volunteered too--but she had spoken up first.

Judith had spent her last night at the rectory inventing exquisite tortures for Branwell.

The sky beyond the coach windows was gray with low, heavy clouds, and the landscape was dreary. The landlord at the inn where they had stopped briefly for a change of horses an hour ago had warned that there had been torrential rain farther north and they were likely to run into it and onto muddy roads, but the stagecoach driver had laughed at the suggestion that he stay at the inn until it was safe to proceed. But sure enough, the road was getting muddier by the minute, even though the rain that had caused it had stopped for a while.

Judith had blocked it all out--the oppressive resentment she felt, the terrible homesickness, the dreary weather, the uncomfortable traveling conditions, and the unpleasant prospect of what lay ahead--and daydreamed instead, inventing a fantasy adventure with a fantasy hero, herself as the unlikely heroine. It offered a welcome diversion for her mind and spirits until moments before the accident.

She was daydreaming about highwaymen. Or, to be more precise, about a highwayman. He was not, of course, like any self-respecting highwayman of the real world--a vicious, dirty, amoral, uncouth robber and cutthroat murderer of hapless travelers. No, indeed. This highwayman was dark and handsome and dashing and laughing--he had white, perfect teeth and eyes that danced merrily behind the slits of his narrow black mask. He galloped across a sun-bright green field and onto the highway, effortlessly controlling his powerful and magnificent black steed with one hand, while he pointed a pistol--unloaded, of course--at the heart of the coachman. He laughed and joked merrily with the passengers as he deprived them of their valuables, and then he tossed back those of the people he saw could ill afford the loss. No . . . No, he returned all of the valuables to all the passengers since he was not a real highwayman at all, but a gentleman bent on vengeance against one particular villian, whom he was expecting to ride along this very road.

He was a noble hero masquerading as a highwayman, with a nerve of steel, a carefree spirit, a heart of gold, and looks to cause every female passenger heart palpitations that had nothing to do with fear.

And then he turned his eyes upon Judith--and the universe stood still and the stars sang in their spheres. Until, that was, he laughed gaily and announced that he would deprive her of the necklace that dangled against her bosom even though it must have been obvious to him that it had almost no money value at all. It was merely something that her . . . her mother had given her on her deathbed, something Judith had sworn never to remove this side of her own grave. She stood up bravely to the highwayman, tossing back her head and glaring unflinchingly into those laughing eyes. She would give him nothing, she told him in a clear, ringing voice that trembled not one iota, even if she must die.

He laughed again as his horse first reared and then pranced about as he brought it easily under control. Then if he could not have the necklace without her, he declared, he would have it with her. He came slowly toward her, large and menacing and gorgeous, and when he was close enough, he leaned down from the saddle, grasped her by the waist with powerful hands--she ignored the problem of the pistol, which he had been brandishing in one hand a moment ago--and lifted her effortlessly upward.

The bottom fell out of her stomach as she lost contact with solid ground, and . . . and she was jerked back to reality. The coach had lost traction on the muddy road and was swerving and weaving and rocking out of control. There was enough time--altogether too much time--to feel blind terror before it went into a long sideways skid, collided with a grassy bank, turned sharply back toward the road, rocked even more alarmingly than before, and finally overturned into a low ditch, coming to a jarring halt half on its side, half on its roof.

When rationality began to return to Judith's mind, everyone seemed to be either screaming or shouting. She was not one of them--she was biting down on both lips instead. The six inside passengers, she discovered, were in a heap together against one side of the coach. Their curses, screams, and groans testified to the fact that most, if not all, of them were alive. Outside she could hear shouts and the whinnying of frightened horses. Two voices, more distinct than any others, were using the most shockingly profane language.

She was alive, Judith thought in some surprise. She was also--she tested the idea gingerly--unhurt, though she felt considerably shaken up. Somehow she appeared to be on top of the heap of bodies. She tried moving, but even as she did so, the door above her opened and someone--the coachman himself--peered down at her.

"Give me your hand, then, miss," he instructed her. "We will have you all out of there in a trice. Lord love us, stop that screeching, woman," he told the talkative woman with a lamentable lack of sympathy considering the fact that he was the one who had overturned them.

It took somewhat longer than a trice, but finally everyone was standing on the grassy edge of the ditch or sitting on overturned bags, gazing hopelessly at the coach, which was obviously not going to be resuming its journey anytime soon. Indeed, even to Judith's unpracticed eye it was evident that the conveyance had sustained considerable damage. There was no sign of any human habitation this side of the horizon. The clouds hung low and threatened rain at any moment. The air was damp and chilly. It was hard to believe that it was summer.

By some miracle, even the outside passengers had escaped serious injury, though two of them were caked with mud and none too happy about it either. There were many ruffled feathers, in fact. There were raised voices and waving fists. Some of the voices were raised in anger, demanding to know why an experienced coachman would bring them forward into peril when he had been advised at the last stop to wait a while. Others were raised in an effort to have their suggestions for what was to be done heard above the hubbub. Still others were complaining of cuts or bruises or other assorted ills. The whining lady had a bleeding wrist.

Judith made no complaint. She had chosen to continue her journey even though she had heard the warning and might have waited for a later coach. She had no suggestions to make either. And she had no injuries. She was merely miserable and looked about her for something to take her mind off the fact that they were all stranded in the middle of nowhere and about to be rained upon. She began to tend those in distress, even though most of the hurts were more imaginary than real. It was something she could do with both confidence and a measure of skill since she had often accompanied her mother on visits to the sick. She bandaged cuts and bruises, using whatever materials came to hand. She listened to each individual account of the mishap over and over, murmuring soothing words while she found seats for the unsteady and fanned the faint. Within minutes she had removed her bonnet, which was getting in her way, and tossed it into the still-overturned carriage. Her hair was coming down, but she did not stop to try to restore it to order. Most people, she found, really did behave rather badly in a crisis, though this one was nowhere near as disastrous as it might have been.

But her spirits were as low as anyone's. This, she thought, was the very last straw. Life could get no drearier than this. She had touched the very bottom. In a sense perhaps that was even a consoling thought. There was surely no farther down to go. There was only up--or an eternal continuation of the same.

"How do you keep so cheerful, dearie?" the woman who had occupied one and a half seats asked her.

Judith smiled at her. "I am alive," she said. "And so are you. What is there not to be cheerful about?"

"I could think of one or two things," the woman said.

But their attention was diverted by a shout from one of the outside passengers, who was pointing off into the distance from which they had come just a few minutes before. A rider was approaching, a single man on horseback. Several of the passengers began hailing him, though he was still too far off to hear them. They were as excited as if a superhuman savior were dashing to their rescue. What they thought one man could do to improve their plight Judith could not imagine. Doubtless they would not either if questioned.

She turned her attention to one of the unfortunate soggy gentlemen, who was dabbing at a bloody scrape on his cheek with a muddy handkerchief and wincing. Perhaps, she thought and stopped herself only just in time from chuckling aloud, the approaching stranger was the tall, dark, noble, laughing highwayman of her daydream. Or perhaps he was a real highwayman coming to rob them, like sitting ducks, of their valuables. Perhaps there was farther down to go after all.

Although he was making a lengthy journey, Lord Rannulf Bedwyn was on horseback--he avoided carriage travel whenever possible. His baggage coach, together with his valet, was trundling along somewhere behind him. His valet, being a cautious, timid soul, had probably decided to stop at the inn an hour or so back when warned of rain by an innkeeper intent on drumming up business.

There must have been a cloudburst in this part of the country not long ago. Even now it looked as if the clouds were just catching their breath before releasing another load on the land beneath. The road had become gradually wetter and muddier until now it was like a glistening quagmire of churned mudflats. He could turn back, he supposed. But it was against his nature to turn tail and flee any challenge, human or otherwise. He must stop at the next inn he came across, though. He might be careless of any danger to himself, but he must be considerate of his horse.

He was in no particular hurry to arrive at Grandmaison Park. His grandmother had summoned him there, as she sometimes did, and he was humoring her as he usually did. He was fond of her even apart from the fact that several years ago she had made him the heir to her unentailed property and fortune though he had two older brothers as well as one younger--plus his two sisters, of course. The reason for his lack of haste was that, yet again, his grandmother had announced that she had found him a suitable bride. It always took a combination of tact and humor and firmness to disabuse her of the notion that she could order his personal life for him. He had no intention of getting married anytime soon. He was only eight and twenty years old. And if and when he did marry, then he would jolly well choose his own bride.

Moments before the stagecoach overturned, Judith Law was deeply immersed in a daydream that had effectively obliterated the unpleasant nature of the present reality.

For the first time in her twenty-two years of existence she was traveling by stagecoach. Within the first mile or two she had been disabused of any notion she might ever have entertained that it was a romantic, adventurous mode of travel. She was squashed between a woman whose girth required a seat and a half of space and a thin, restless man who was all sharp angles and elbows and was constantly squirming to find a more comfortable position, digging her in uncomfortable and sometimes embarrassing places as he did so. A portly man opposite snored constantly, adding considerably to all the other noises of travel. The woman next to him talked unceasingly to anyone unfortunate or unwise enough to make eye contact with her, relating the sorry story of her life in a tone of whining complaint. From the quiet man on the other side of her wafted the odors of uncleanness mingled with onions and garlic. The coach rattled and vibrated and jarred over every stone and pothole in its path, or so it seemed to Judith.

Yet for all the discomforts of the road, she was not eager to complete the journey. She had just left behind the lifelong familiarity of Beaconsfield and home and family and did not expect to return to them for a long time, if ever. She was on her way to live at her Aunt Effingham's. Life as she had always known it had just ended. Though nothing had been stated explicitly in the letter her aunt had written to Papa, it had been perfectly clear to Judith that she was not going to be an honored, pampered guest at Harewood Grange, but rather a poor relation, expected to earn her keep in whatever manner her aunt and uncle and cousins and grandmother deemed appropriate. Starkly stated, she could expect only dreariness and drudgery ahead--no beaux, no marriage, no home and family of her own. She was about to become one of those shadowy, fading females with whom society abounded, dependent upon their relatives, unpaid servants to them.

It had been extraordinarily kind of Aunt Effingham to invite her, Papa had said--except that her aunt, her father's sister, who had made an extremely advantageous marriage to the wealthy, widowed Sir George Effingham when she was already past the first bloom of youth, was not renowned for kindness.

And it was all because of Branwell, the fiend, who deserved to be shot and then hanged, drawn, and quartered for his thoughtless extravagances--Judith had not had a kind thought to spare for her younger brother in many weeks. And it was because she was the second daughter, the one without any comforting label to make her continued presence at home indispensable. She was not the eldest--Cassandra was a year older than she. She was certainly not the beauty--her younger sister Pamela was that. And she was not the baby--seventeen-year-old Hilary had that dubious distinction. Judith was the embarrassingly awkward one, the ugly one, the always cheerful one, the dreamer.

Judith was the one everyone had turned and looked at when Papa came to the sitting room and read Aunt Effingham's letter aloud. Papa had fallen into severe financial straits and must have written to his sister to ask for just the help she was offering. They all knew what it would mean to the one chosen to go to Harewood. Judith had volunteered. They had all cried when she spoke up, and her sisters had all volunteered too--but she had spoken up first.

Judith had spent her last night at the rectory inventing exquisite tortures for Branwell.

The sky beyond the coach windows was gray with low, heavy clouds, and the landscape was dreary. The landlord at the inn where they had stopped briefly for a change of horses an hour ago had warned that there had been torrential rain farther north and they were likely to run into it and onto muddy roads, but the stagecoach driver had laughed at the suggestion that he stay at the inn until it was safe to proceed. But sure enough, the road was getting muddier by the minute, even though the rain that had caused it had stopped for a while.

Judith had blocked it all out--the oppressive resentment she felt, the terrible homesickness, the dreary weather, the uncomfortable traveling conditions, and the unpleasant prospect of what lay ahead--and daydreamed instead, inventing a fantasy adventure with a fantasy hero, herself as the unlikely heroine. It offered a welcome diversion for her mind and spirits until moments before the accident.

She was daydreaming about highwaymen. Or, to be more precise, about a highwayman. He was not, of course, like any self-respecting highwayman of the real world--a vicious, dirty, amoral, uncouth robber and cutthroat murderer of hapless travelers. No, indeed. This highwayman was dark and handsome and dashing and laughing--he had white, perfect teeth and eyes that danced merrily behind the slits of his narrow black mask. He galloped across a sun-bright green field and onto the highway, effortlessly controlling his powerful and magnificent black steed with one hand, while he pointed a pistol--unloaded, of course--at the heart of the coachman. He laughed and joked merrily with the passengers as he deprived them of their valuables, and then he tossed back those of the people he saw could ill afford the loss. No . . . No, he returned all of the valuables to all the passengers since he was not a real highwayman at all, but a gentleman bent on vengeance against one particular villian, whom he was expecting to ride along this very road.

He was a noble hero masquerading as a highwayman, with a nerve of steel, a carefree spirit, a heart of gold, and looks to cause every female passenger heart palpitations that had nothing to do with fear.

And then he turned his eyes upon Judith--and the universe stood still and the stars sang in their spheres. Until, that was, he laughed gaily and announced that he would deprive her of the necklace that dangled against her bosom even though it must have been obvious to him that it had almost no money value at all. It was merely something that her . . . her mother had given her on her deathbed, something Judith had sworn never to remove this side of her own grave. She stood up bravely to the highwayman, tossing back her head and glaring unflinchingly into those laughing eyes. She would give him nothing, she told him in a clear, ringing voice that trembled not one iota, even if she must die.

He laughed again as his horse first reared and then pranced about as he brought it easily under control. Then if he could not have the necklace without her, he declared, he would have it with her. He came slowly toward her, large and menacing and gorgeous, and when he was close enough, he leaned down from the saddle, grasped her by the waist with powerful hands--she ignored the problem of the pistol, which he had been brandishing in one hand a moment ago--and lifted her effortlessly upward.

The bottom fell out of her stomach as she lost contact with solid ground, and . . . and she was jerked back to reality. The coach had lost traction on the muddy road and was swerving and weaving and rocking out of control. There was enough time--altogether too much time--to feel blind terror before it went into a long sideways skid, collided with a grassy bank, turned sharply back toward the road, rocked even more alarmingly than before, and finally overturned into a low ditch, coming to a jarring halt half on its side, half on its roof.

When rationality began to return to Judith's mind, everyone seemed to be either screaming or shouting. She was not one of them--she was biting down on both lips instead. The six inside passengers, she discovered, were in a heap together against one side of the coach. Their curses, screams, and groans testified to the fact that most, if not all, of them were alive. Outside she could hear shouts and the whinnying of frightened horses. Two voices, more distinct than any others, were using the most shockingly profane language.

She was alive, Judith thought in some surprise. She was also--she tested the idea gingerly--unhurt, though she felt considerably shaken up. Somehow she appeared to be on top of the heap of bodies. She tried moving, but even as she did so, the door above her opened and someone--the coachman himself--peered down at her.

"Give me your hand, then, miss," he instructed her. "We will have you all out of there in a trice. Lord love us, stop that screeching, woman," he told the talkative woman with a lamentable lack of sympathy considering the fact that he was the one who had overturned them.

It took somewhat longer than a trice, but finally everyone was standing on the grassy edge of the ditch or sitting on overturned bags, gazing hopelessly at the coach, which was obviously not going to be resuming its journey anytime soon. Indeed, even to Judith's unpracticed eye it was evident that the conveyance had sustained considerable damage. There was no sign of any human habitation this side of the horizon. The clouds hung low and threatened rain at any moment. The air was damp and chilly. It was hard to believe that it was summer.

By some miracle, even the outside passengers had escaped serious injury, though two of them were caked with mud and none too happy about it either. There were many ruffled feathers, in fact. There were raised voices and waving fists. Some of the voices were raised in anger, demanding to know why an experienced coachman would bring them forward into peril when he had been advised at the last stop to wait a while. Others were raised in an effort to have their suggestions for what was to be done heard above the hubbub. Still others were complaining of cuts or bruises or other assorted ills. The whining lady had a bleeding wrist.

Judith made no complaint. She had chosen to continue her journey even though she had heard the warning and might have waited for a later coach. She had no suggestions to make either. And she had no injuries. She was merely miserable and looked about her for something to take her mind off the fact that they were all stranded in the middle of nowhere and about to be rained upon. She began to tend those in distress, even though most of the hurts were more imaginary than real. It was something she could do with both confidence and a measure of skill since she had often accompanied her mother on visits to the sick. She bandaged cuts and bruises, using whatever materials came to hand. She listened to each individual account of the mishap over and over, murmuring soothing words while she found seats for the unsteady and fanned the faint. Within minutes she had removed her bonnet, which was getting in her way, and tossed it into the still-overturned carriage. Her hair was coming down, but she did not stop to try to restore it to order. Most people, she found, really did behave rather badly in a crisis, though this one was nowhere near as disastrous as it might have been.

But her spirits were as low as anyone's. This, she thought, was the very last straw. Life could get no drearier than this. She had touched the very bottom. In a sense perhaps that was even a consoling thought. There was surely no farther down to go. There was only up--or an eternal continuation of the same.

"How do you keep so cheerful, dearie?" the woman who had occupied one and a half seats asked her.

Judith smiled at her. "I am alive," she said. "And so are you. What is there not to be cheerful about?"

"I could think of one or two things," the woman said.

But their attention was diverted by a shout from one of the outside passengers, who was pointing off into the distance from which they had come just a few minutes before. A rider was approaching, a single man on horseback. Several of the passengers began hailing him, though he was still too far off to hear them. They were as excited as if a superhuman savior were dashing to their rescue. What they thought one man could do to improve their plight Judith could not imagine. Doubtless they would not either if questioned.

She turned her attention to one of the unfortunate soggy gentlemen, who was dabbing at a bloody scrape on his cheek with a muddy handkerchief and wincing. Perhaps, she thought and stopped herself only just in time from chuckling aloud, the approaching stranger was the tall, dark, noble, laughing highwayman of her daydream. Or perhaps he was a real highwayman coming to rob them, like sitting ducks, of their valuables. Perhaps there was farther down to go after all.

Although he was making a lengthy journey, Lord Rannulf Bedwyn was on horseback--he avoided carriage travel whenever possible. His baggage coach, together with his valet, was trundling along somewhere behind him. His valet, being a cautious, timid soul, had probably decided to stop at the inn an hour or so back when warned of rain by an innkeeper intent on drumming up business.

There must have been a cloudburst in this part of the country not long ago. Even now it looked as if the clouds were just catching their breath before releasing another load on the land beneath. The road had become gradually wetter and muddier until now it was like a glistening quagmire of churned mudflats. He could turn back, he supposed. But it was against his nature to turn tail and flee any challenge, human or otherwise. He must stop at the next inn he came across, though. He might be careless of any danger to himself, but he must be considerate of his horse.

He was in no particular hurry to arrive at Grandmaison Park. His grandmother had summoned him there, as she sometimes did, and he was humoring her as he usually did. He was fond of her even apart from the fact that several years ago she had made him the heir to her unentailed property and fortune though he had two older brothers as well as one younger--plus his two sisters, of course. The reason for his lack of haste was that, yet again, his grandmother had announced that she had found him a suitable bride. It always took a combination of tact and humor and firmness to disabuse her of the notion that she could order his personal life for him. He had no intention of getting married anytime soon. He was only eight and twenty years old. And if and when he did marry, then he would jolly well choose his own bride.