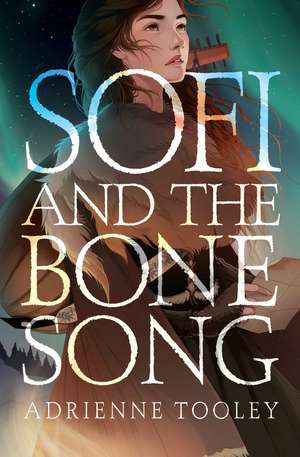

Sofi and the Bone Song

Autor Adrienne Tooleyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 mar 2023 – vârsta de la 12 ani

Music runs in Sofi’s blood.

Her father is a Musik, one of only five musicians in the country licensed to compose and perform original songs. In the kingdom of Aell, where winter is endless and magic is accessible to all, there are strict anti-magic laws ensuring music remains the last untouched art.

Sofi has spent her entire life training to inherit her father’s title. But on the day of the auditions, she is presented with unexpected competition in the form of Lara, a girl who has never before played the lute. Yet somehow, to Sofi’s horror, Lara puts on a performance that thoroughly enchants the judges.

Almost like magic.

The same day Lara wins the title of Musik, Sofi’s father dies, and a grieving Sofi sets out to prove Lara is using illegal magic in her performances. But the more time she spends with Lara, the more Sofi begins to doubt everything she knows about her family, her music, and the girl she thought was her enemy.

As Sofi works to reclaim her rightful place as a Musik, she is forced to face the dark secrets of her past and the magic she was trained to avoid—all while trying not to fall for the girl who stole her future.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 58.75 lei 3-5 săpt. | +14.00 lei 4-10 zile |

| Margaret K. McElderry Books – 29 mar 2023 | 58.75 lei 3-5 săpt. | +14.00 lei 4-10 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 113.31 lei 3-5 săpt. | +36.33 lei 4-10 zile |

| Margaret K. McElderry Books – 8 iun 2022 | 113.31 lei 3-5 săpt. | +36.33 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 58.75 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 88

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.24€ • 11.59$ • 9.49£

11.24€ • 11.59$ • 9.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 februarie

Livrare express 24-30 ianuarie pentru 23.99 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534484375

ISBN-10: 153448437X

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: f-c cvr--sfx: spot gloss

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Colecția Margaret K. McElderry Books

ISBN-10: 153448437X

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: f-c cvr--sfx: spot gloss

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Colecția Margaret K. McElderry Books

Notă biografică

Adrienne Tooley grew up in Southern California, majored in musical theater in Pittsburgh, and now lives in Brooklyn with her wife, six guitars, and a banjo. In addition to writing novels, she is a singer/songwriter who has currently released three indie-folk EPs. She’s the author of Sweet & Bitter Magic and Sofi & the Bone Song. You can find her online at AdrienneTooley.com.

Extras

Chapter OneONE

THE KING came to Juuri on a third day, which meant that upon his arrival, Sofi was otherwise engaged. While her father welcomed King Jovan and his attendants in their parlor, Sofi pressed her knees against the firm floor of her closet and called out to the Muse.

“Sing to me, O Muse, for without you I am lost. Pray for me, O Muse, for without you I am empty. Let your notes be played, let your song be sung. I will hear you, if only you will speak to me. Let me be worthy—” Her voice broke on the word, as it did each time she spoke the prayer. “Let me be heard.”

Even though Sofi knew her father was downstairs, she could practically hear him on the other side of the door, commanding her to repeat the prayer: “Again.”

She obeyed. Even when Frederik Ollenholt was elsewhere, his voice still echoed in her head, as sharp and cold as a fresh layer of snow.

“Sing to me, O Muse, for without you I am lost.”

Sofi’s father was not known for his kindness, but then, kindness and talent were not one and the same. What Frederik Ollenholt lacked in niceties he made up for in his command of the Muse, in the intricate, complex music that poured from his fingers to his lute. As one of the five members of the Guild of Musiks and the only lutenist licensed to cross the border of their Kingdom of Aell into the wider world, her father didn’t need to be kind. He needed talent. So if Sofi ever wanted to become her father’s Apprentice—which she desperately, gut-wrenchingly did—she needed to ensure the Muse was on her side.

Sofi fumbled in the darkness for the dress nearest to her, tugging it from its hanger and pulling it tightly around her shoulders like a blanket. “Pray for me, O Muse, for without you I am empty.”

For ten of the sixteen years of her life, Sofi had prayed to the Muse every third day, yet there was something about that exact moment—the scratch of wool against her cheek, the muted echo of the royal party downstairs—that made the prayer’s words ring differently in her ears. This time, her voice echoed around the closet like Sofi was at the bottom of a well, the prayer reverberating against ice and stone, hollow and sprawling.

Sprawling. That was it.

Sofi got to her feet so quickly she nearly smacked her head against the top of the closet. She had long grown out of the small, cramped space, but the dark helped her focus. Concentration was especially important on third days.

Third days were for praying.

Sunlight flooded into the small space as Sofi pushed open the closet door and spilled into her bedroom, heading directly for her desk. She rifled through the endless sheaf of papers littering its surface until she found a scrap that wasn’t covered with words she liked or the fragment of a concept or the sketch of a song. She fumbled for a pencil that had not yet been sharpened all the way to its nub, one that was long enough to still fit between her fingers.

Sofi scrambled to put down the lyric that had sprung fully formed into her head, her left hand smearing her words as it hurried across the page. She’d been working on a song about Saint Brielle, but the final line of the chorus had eluded her for days.

Now the Muse had offered Sofi the missing piece, laid it out as neatly as a carpet unfurled at the feet of a king: Until death’s final, sprawling song called them back where they belonged.

She shivered gleefully. This line was further proof that Sofi’s devotion to the Muse would always be rewarded. Proof that she was the clear choice to be named her father’s Apprentice, the first step toward becoming a Musik in her own right.

Sofi wasn’t the only one who knew it, either. Only yesterday, another of Frederik’s students, a girl called Neha who had been studying with Sofi’s father for nearly five years, had walked in on Sofi composing in the parlor and sighed dramatically.

“I almost don’t know why I bother,” she had grumbled as Sofi put the finishing touches on the thirteenth verse of “The Song of Saint Brielle.” “The words fall out of you so effortlessly, it’s almost like magic.”

While to a non-musician, it might have sounded like a compliment, to Sofi those were fighting words. Using magic in music went against the highest tenet of the Guild of Musiks. It was a crime that could get a musician-in-training Redlisted, losing them the right to ever perform again.

“It’s because I practice, Neha.” Sofi had scowled from the settee. “You should try it sometime.”

“Someone’s testy.” Neha had tsked. “They do say that using too many Papers makes a person mean. Of course, I wouldn’t know,” she’d said smugly, tucking a strand of long black hair behind her ear, showing off the backs of her hands. Her brown skin was clearly absent of the words that identified a Paper-caster. On Neha’s dark shade of skin, the words would have gleamed as white as snow.

By then Sofi had removed her lute from her lap and rested her hands on her knees. Had she been employing Paper magic, the words would have shone black as ink on her white skin. “Why don’t you come take a closer look if you’re so concerned about the integrity of my music?”

“No, thank you.” Neha had rolled her eyes. “I’ve heard enough stories of your famous temper. I don’t need firsthand experience. Now, if you’ll excuse me, it’s time for my lesson.” She had flounced away, leaving Sofi stewing.

The implication that she was using magic in her music was insulting. The Papers Neha had mentioned had been published thirty years prior, after the Hollow God’s gospel spread throughout the world. To escape persecution from his fanatical followers, witches fled north to Aell, whose aging, greedy King Ashe had offered the covens safety and security within his borders in exchange for some of their magic. The desperate witches worked with his men of science to make magic accessible to all. Thus the Papers were published.

Now, for a price, anyone in Aell could purchase a piece of parchment, offer it a drop of blood, and reap the rewards of that particular spell. A Paper for “sketch” would allow the Paper-caster to draw a perfect rendering of the king. A Paper for “chignon” would guide the Paper-caster’s hand to pin their hair into a perfect twist. A Paper for “warmth” would start a fire, and a Paper for “blush” would turn the Paper-caster’s cheeks as pink as a sunrise without the aid of face paint.

Overnight, the Papers had turned the extraordinary ordinary. And if there was one thing Sofi Ollenholt refused to be, it was ordinary.

The implication that she was using magic in her music was also damning. Musiks were musicians who lived, composed, and performed without the assistance of magic—Paper or otherwise. Any student hoping to ascend to the rank of Apprentice had to keep their hands clean and their art pure.

Even the rumor of a musician using magic was enough to destroy their career entirely—and hers hadn’t even begun.

Sofi shook away the memory of the interaction. Neha had always been jealous of Sofi’s innate ability, her natural talent. Sofi would not let the other girl’s baseless accusations get to her. She had never even touched a Paper, so strongly did she eschew magic, so hard did she work to keep herself clean. Deserving. Worthy of one day becoming a Musik herself.

Sofi grabbed her lute from its place on her pillow and brushed the strings lightly, patiently adjusting the tuning pegs. Aell’s perpetual cold meant her strings tended to tense, and if she wasn’t tender with them, the catgut would snap. The body of her lute pressed gently against her stomach, held in place by the crook of her right arm. That hand plucked the strings while her left hand fingered the notes up and down the instrument’s neck.

That shiver returned, the hair on her arms standing at attention as Sofi coaxed sound from her instrument, notes ringing out soft and sincere in her small room. While sometimes the more familiar pieces of her training routine felt tedious, this part never got old: the playing. Piecing her words and her melodies together. Using her hands and her voice and her mind to create something entirely new, something that would not exist were it not for her.

When Sofi played, she had power.

“Did bright Brielle put forth the snow, from where death’s sweaty hand would go,” Sofi sang, her left ring finger pressed tight upon the two strings of her lute’s fourth course. “The devil’s hot, candescent glow did urge her boldly on.”

Sofi played her way through the story of Saint Brielle, the woman who ended the devil’s scorching summer nearly two centuries ago. As Sofi sang her praise for the saint who commanded winter’s wind, the snow outside her bedroom window turned to sleet, hammering against the glass and displacing the crow that had been roosting beneath the slats of the roof. Ice collected in the window’s corners as the view of the snowcapped trees was blurred by wretched, unending white. Sofi sighed bitterly, her fingers falling from her instrument.

Lingering seasons weren’t uncommon in Aell. The Saint’s Summer, when Saint Evaline brought forth the harvest from the icy ground, had come after six years of cold. Saint Brielle’s winter ended ten agonizing years of summer. But Aell’s current winter was pushing seventeen years, longer than any in the history books or the epic tales sung by Musiks.

Sixteen years of snow. A season as old as Sofi.

The cold was all she’d ever known.

She pressed a hand to the frigid windowpane above her desk. Heat from her fingertips leached onto the glass, leaving marks that disappeared almost instantly. Sofi was afraid of fading away that easily, of leaving not a single visible mark on the world.

It was why she worked so hard. Played so often. Practiced so frequently. Why she obeyed her father’s orders and followed the training routine he’d set for her. So many years after its creation, it now held the monotonous familiarity of a lullaby: The first day was for listening, the second for wanting, the third for praying, the fourth for feeling, and the fifth for repenting. But sixth days were special.

Sixth days were for music.

It was a routine more extreme than the methods required of her father’s other students. But that was by choice. Sofi had always been willing to work harder. Push herself further. She would do whatever it took to become her father’s Apprentice and finally be able to perform publicly. Without the Apprentice title, musicians could only play and compose within their own homes. Sofi was far too talented for her songs to be confined within the four walls of her bedroom.

She placed her fingers back on the lute’s strings, picking the song up from its second chorus.

“That’s new.”

Sofi yelped, nearly falling off her chair as Jakko, her best friend and her father’s only live-in student, smiled at her from the doorway, his glossy black curls tumbling dramatically into his eyes.

“What are you doing in here?” Sofi settled her lute carefully back into its case. “The king’s downstairs. Shouldn’t you be groveling?”

Jakko sighed dramatically and flung himself onto her bed, hugging a pillow to his chest. “Jasper didn’t come this time. What’s the point of making an appearance if the prince can’t see me?”

Sofi rolled her eyes as she swept the papers littering her desk into a haphazard pile. “I still think that the alliteration is a little showy, even for you.” She threw her bare foot onto the mattress, nudging Jakko’s side. “I mean, Jasper and Jakko?” She wrinkled her nose in mock distaste. Jakko reached out a hand to tickle her, his golden-brown fingers warm against her toes. She kicked his hand away playfully.

“What are you wearing tonight?” Sofi cast a glance at the dress form that held her ruby-red gown for that evening’s performance. Most days she opted for shapeless, gray wool shifts. Function rather than form. It was a shock each time her father performed publicly: the jewel-toned dresses that appeared in her bedroom; the paint Marie, their housekeeper, would smear on her lips and cheeks; the way Sofi was flaunted about. That public display of self was a different sort of performance entirely.

“Well”—Jakko ran a hand through his curls—“now that Jasper’s not here, I have half a mind not to attend the performance at all.”

“You are,” Sofi laughed, “the least devoted student my father has ever had.”

“Untrue,” Jakko volleyed back. “Remember Thea?”

Sofi put a hand to her heart in mock pain. “Low blow.” Thea had been Sofi’s first crush. Luckily, there had never been any awkwardness or competition between the two of them because Thea was so useless at the lute that Sofi’s father had refused to teach her any further after only three lessons.

Frederik Ollenholt had quite a lot of what he called “artistic integrity” and what other people called “impossible standards.”

“All my blows are low.” Jakko wagged a finger at her. “I should’ve been a flautist.”

Sofi snorted. “You should have. There wasn’t any competition for that Apprenticeship. The only musician that showed up to audition was Therolious Ambor’s own son, Barton.” She made a face her best friend didn’t return. Jakko had suddenly become very interested in her duvet cover.

“What’s wrong?” Sofi moved onto the bed, sticking a finger under Jakko’s chin and tilting it up, forcing him to meet her eyes.

“I’m almost eighteen, Sof.” His voice was soft like a swaying breeze. “If your father doesn’t take his Apprentice in the next few months, I’ve got nothing.” His eyes flitted away from hers again.

“And?” Sofi prompted, even as her stomach squirmed guiltily. She knew Jakko well enough to know when he had more to say.

“And…,” he started, looking pained. “If he chooses me, what does that mean for you?”

It was Sofi’s turn to look away.

While anyone could—for the right price—take lessons from a Musik, the position of a Musik’s Apprentice was both highly coveted and highly competitive. Each Musik took on only one Apprentice in their lifetime. That Apprentice was granted their mentor’s treble clef pin, which allowed them to inherit the title of Musik when the reigning Musik retired or passed on. If Sofi wasn’t chosen as her father’s Apprentice, she would lose the chance of ever becoming a Musik, and the talent she had spent her life honing would become nothing more meaningful than a party trick. Without the title of Musik, Sofi would never make her mark on the world.

“I’d figure something out.” But Sofi’s lie fell flat. There was no other option.

Not for her.

Not every musician had the willpower or discipline to become a Musik. But Sofi, with a dead mother and a father who spent most of his life on the road, had nothing but time. She had dedicated her entire life to ensuring the Muse was on her side. She had been handed a lute at four years old and could read music before she could write her own name. She whiled away hours studying theory, poring over lyrics and rhyme schemes. By the age of eight, she was performing works that tripped up her father’s most seasoned students. Once, when she was ten, she taught herself to play a song holding her lute upside down, just to prove that she could.

But beyond her hard work and dedication, and perhaps most importantly, Sofi was good. Her technical skill was unparalleled; she could play even the most complex melodies after hearing them only once. Sofi was so focused on perfection that any mistake she made—missing a note or striking an errant string, falling out of time or taking a beat too long to make a transition—became a learning experience, an obsession, the same phrase played over and over until she was certain she would never waver again. Even her father, with his signature scrutiny and painfully expressive features, found less and less to criticize as the years went on.

Sofi adored Jakko. He was a good lutenist and an even better friend. But the title of Apprentice would one day be hers.

It had to be.

“Liar.” But Jakko’s voice held no anger, only familiar resignation. He rolled onto his stomach, cheek pressed against her pillow. “Do you ever wish we loved an art that wasn’t so competitive? One that allowed us to use Papers?”

Sofi made a face, thinking of Neha. “Of course not.” She flopped over, nuzzling up next to Jakko. “Anyone can use a Paper to pen a poem about the queen or paint a picture of the king and call themselves an artist. But we create freely, with clean hands and talent alone.”

She offered her hand to Jakko, who pushed her unmarked skin away with a roll of his eyes. There was never any speculation as to which spell a Paper-caster had chosen to employ. Heartbreak, a hand would read, if a poet used a Paper to conjure the feeling necessary to write a poem of longing and loss. Flame, it would warn, if the caster needed fire. It was not uncommon to see Paper-casters whose hands were covered with so many words they appeared to be wearing gloves.

When the Paper’s power faded, so too would the word. The hand that had once flawlessly sketched the face of a king would go back to barely being able to draw a straight line. The fire that had been conjured would begin to dim. If an artist wanted to finish their sketch, if an innkeeper wanted to restoke the flames, first they would need to purchase another Paper.

Sofi shrugged. “What can I say? I love feeling superior.”

Jakko pushed himself up onto his elbows and frowned. “Do you love to feel superior or do you love to suffer? Because, Sofi, those bruises look nasty.”

Sofi swiftly rearranged her skirt to cover her knees. “I do what I have to for my art.” Her voice was hard.

“Of course.” Jakko’s tone was too casual. “Still, don’t you find it odd that your father never included anything like that in my training routine? No praying? No repenting?”

“I suppose,” Sofi said. But what she meant was no. Sofi had been practicing advanced training methods since she was a child. Methods her father’s other students weren’t privy to. Rather than making her feel isolated or alone, this distinction was further proof that becoming a Musik was her destiny.

Sofi reached for Jakko’s hand, twining her fingers in his. His palm was sweaty in that overheated-teenage-boy way. Jakko had been studying with Frederik since Sofi was thirteen and he fifteen. Three years later, they were practically inseparable, no dream too sincere, no competition cutthroat enough to keep them apart. It wouldn’t always be this way, but Sofi knew all too well what it was like to be alone. She would hold on as long as she could to his bright laughter, the way he lit up every room. The way he trusted her.

The way she almost trusted him.

“How come Marie never puts satin sheets on my bed?” Jakko rubbed his cheek theatrically across Sofi’s pillow.

“Because you steal her cheese.” Sofi giggled, squeezing his hand. She wished there were a way for them both to play music, together. That Jakko would not be relegated to nothingness when she was named her father’s successor.

Jakko made an affronted noise. “That’s true,” he finally conceded. “I do.”

“I knew it,” Sofi gasped, gripping Jakko’s wrist.

“Ow,” Jakko whined. “Your calluses are so rough.”

Sofi let go of him, waggling her fingers in his face. “I have the prettiest hands you’ve ever seen.”

“That’s not necessarily what I’d call them.” Jakko swatted at her, finally pushing himself up and off her bed. “Now, come on, Lady Ollenholt.” He offered her his hand. “Let’s go greet the king.”

By the time Sofi and Jakko arrived in the parlor, the pastries had been reduced to crumbs and the tea had gone cold. Marie tutted beneath her breath as she met them in the doorway. The housekeeper reached up to tuck one of Sofi’s unruly brown curls tenderly behind her ear.

“There you are.” Frederik’s expression was pinched despite the light bravado of his voice.

“Jakko. Sofi.” King Jovan’s voice was a deep bass that resonated warmly within his chest. He got to his feet, unmistakably royal, his brown skin flawlessly smooth, his beard closely cropped, his clothes perfectly tailored, his penchant for gold striking against his warm complexion and his glittering brown eyes. “Give your king a hug, then.” He opened his arms to Sofi, looking for all the world more fatherly than Frederik.

Sofi moved to him, inhaling the scent of sap and pine and the sweet sharp slice of perfume. Her father wasn’t a hugger, and Marie, despite her mothering tendencies, preferred to fuss rather than to envelop. It was not lost on Sofi how absurd it was that the most consistent embraces she received were from the king of her country.

“How are you, Your Majesty?” Sofi asked as they broke apart. Up close, there were shadows beneath his eyes.

“I look a sight, don’t I?” the king asked humorlessly. “I’ve just come from a meeting of the Council of Regents. Twenty years a king, yet I’m still paying for the sins of my father.”

Sofi’s brow furrowed sympathetically. The Papers commissioned by Jovan’s father, King Ashe, had generated incredible wealth for their country. But that power had increased Ashe’s greed tenfold, and he’d soon set his sights beyond Aell to the countries who served the Hollow God. The Hollow God’s followers lived by the pillars of piety, simplicity, hard work, and suffering. Unregulated magic had no place in their world.

So King Ashe was careful to position the Papers as everything witches were not: careful, contained, and controllable. Yet once the deals were done, the new Papers he’d sold hadn’t worked as the originals had. This magic turned volatile and downright dangerous. Instead of a Paper that commanded water buckets to carry themselves, the Kingdom of Tique faced a slew of slimy newts that sent a sickness through the country’s waterways. Heinous burns cropped up on the faces of Dolgesh citizens who had used glamours to polish their appearances. And when the Queen of Roth’s personal chef used a Paper to speed up the simmering of a stew, the monarch found herself suddenly and violently ill.

The Council of Regents—made up of rulers from those neighboring monarchies—began to suspect that Ashe had been using the power of witches to expand his empire by weakening theirs. In retribution, they built the Gate, which closed their borders to all citizens of Aell, keeping Aellinians alone. Contained.

“Of course,” the king continued, his hand heavy on Sofi’s shoulder, “you wouldn’t know anything about that. I cannot wait for your father to transport us all with his performance tonight. I do believe the entire Guild will be in attendance.” His eyes fell tenderly on Frederik like a mother bird to a hatchling.

The five members of the Guild of Musiks were King Jovan’s peace offering to the Council of Regents—proof that Aell held no ill will against its neighbors. That its citizens could create even when their hands were clean of magic. The instruments of the Guild—lute, lyre, drum, flute, and accordion—were the only ones allowed to be played in public. Musiks were the only Aellinians allowed through the Gate.

King Jovan had high hopes that it would be the Guild who would ultimately convince the Council to reopen the border and let Aell rejoin the world.

“Yes,” the king continued, “it’s shaping up to be a most exciting evening.”

Sofi could feel Jakko’s eyes on the back of her neck. These days, gathering the entire Guild in one room was a feat. When Sofi was younger, she had accompanied Frederik to many a performance, traveling by coach to towns all across Aell to see his fellow Musiks perform in gilded theaters. But those performances had been fewer and farther between as of late.

Tonight was already a significant occasion. But as the king’s eyes glittered mischievously, reflecting the roaring fire in the hearth behind him, it was clear something greater was afoot.

“Certainly, Your Majesty,” Sofi agreed, curiosity mounting. “A most exciting evening indeed.”

THE KING came to Juuri on a third day, which meant that upon his arrival, Sofi was otherwise engaged. While her father welcomed King Jovan and his attendants in their parlor, Sofi pressed her knees against the firm floor of her closet and called out to the Muse.

“Sing to me, O Muse, for without you I am lost. Pray for me, O Muse, for without you I am empty. Let your notes be played, let your song be sung. I will hear you, if only you will speak to me. Let me be worthy—” Her voice broke on the word, as it did each time she spoke the prayer. “Let me be heard.”

Even though Sofi knew her father was downstairs, she could practically hear him on the other side of the door, commanding her to repeat the prayer: “Again.”

She obeyed. Even when Frederik Ollenholt was elsewhere, his voice still echoed in her head, as sharp and cold as a fresh layer of snow.

“Sing to me, O Muse, for without you I am lost.”

Sofi’s father was not known for his kindness, but then, kindness and talent were not one and the same. What Frederik Ollenholt lacked in niceties he made up for in his command of the Muse, in the intricate, complex music that poured from his fingers to his lute. As one of the five members of the Guild of Musiks and the only lutenist licensed to cross the border of their Kingdom of Aell into the wider world, her father didn’t need to be kind. He needed talent. So if Sofi ever wanted to become her father’s Apprentice—which she desperately, gut-wrenchingly did—she needed to ensure the Muse was on her side.

Sofi fumbled in the darkness for the dress nearest to her, tugging it from its hanger and pulling it tightly around her shoulders like a blanket. “Pray for me, O Muse, for without you I am empty.”

For ten of the sixteen years of her life, Sofi had prayed to the Muse every third day, yet there was something about that exact moment—the scratch of wool against her cheek, the muted echo of the royal party downstairs—that made the prayer’s words ring differently in her ears. This time, her voice echoed around the closet like Sofi was at the bottom of a well, the prayer reverberating against ice and stone, hollow and sprawling.

Sprawling. That was it.

Sofi got to her feet so quickly she nearly smacked her head against the top of the closet. She had long grown out of the small, cramped space, but the dark helped her focus. Concentration was especially important on third days.

Third days were for praying.

Sunlight flooded into the small space as Sofi pushed open the closet door and spilled into her bedroom, heading directly for her desk. She rifled through the endless sheaf of papers littering its surface until she found a scrap that wasn’t covered with words she liked or the fragment of a concept or the sketch of a song. She fumbled for a pencil that had not yet been sharpened all the way to its nub, one that was long enough to still fit between her fingers.

Sofi scrambled to put down the lyric that had sprung fully formed into her head, her left hand smearing her words as it hurried across the page. She’d been working on a song about Saint Brielle, but the final line of the chorus had eluded her for days.

Now the Muse had offered Sofi the missing piece, laid it out as neatly as a carpet unfurled at the feet of a king: Until death’s final, sprawling song called them back where they belonged.

She shivered gleefully. This line was further proof that Sofi’s devotion to the Muse would always be rewarded. Proof that she was the clear choice to be named her father’s Apprentice, the first step toward becoming a Musik in her own right.

Sofi wasn’t the only one who knew it, either. Only yesterday, another of Frederik’s students, a girl called Neha who had been studying with Sofi’s father for nearly five years, had walked in on Sofi composing in the parlor and sighed dramatically.

“I almost don’t know why I bother,” she had grumbled as Sofi put the finishing touches on the thirteenth verse of “The Song of Saint Brielle.” “The words fall out of you so effortlessly, it’s almost like magic.”

While to a non-musician, it might have sounded like a compliment, to Sofi those were fighting words. Using magic in music went against the highest tenet of the Guild of Musiks. It was a crime that could get a musician-in-training Redlisted, losing them the right to ever perform again.

“It’s because I practice, Neha.” Sofi had scowled from the settee. “You should try it sometime.”

“Someone’s testy.” Neha had tsked. “They do say that using too many Papers makes a person mean. Of course, I wouldn’t know,” she’d said smugly, tucking a strand of long black hair behind her ear, showing off the backs of her hands. Her brown skin was clearly absent of the words that identified a Paper-caster. On Neha’s dark shade of skin, the words would have gleamed as white as snow.

By then Sofi had removed her lute from her lap and rested her hands on her knees. Had she been employing Paper magic, the words would have shone black as ink on her white skin. “Why don’t you come take a closer look if you’re so concerned about the integrity of my music?”

“No, thank you.” Neha had rolled her eyes. “I’ve heard enough stories of your famous temper. I don’t need firsthand experience. Now, if you’ll excuse me, it’s time for my lesson.” She had flounced away, leaving Sofi stewing.

The implication that she was using magic in her music was insulting. The Papers Neha had mentioned had been published thirty years prior, after the Hollow God’s gospel spread throughout the world. To escape persecution from his fanatical followers, witches fled north to Aell, whose aging, greedy King Ashe had offered the covens safety and security within his borders in exchange for some of their magic. The desperate witches worked with his men of science to make magic accessible to all. Thus the Papers were published.

Now, for a price, anyone in Aell could purchase a piece of parchment, offer it a drop of blood, and reap the rewards of that particular spell. A Paper for “sketch” would allow the Paper-caster to draw a perfect rendering of the king. A Paper for “chignon” would guide the Paper-caster’s hand to pin their hair into a perfect twist. A Paper for “warmth” would start a fire, and a Paper for “blush” would turn the Paper-caster’s cheeks as pink as a sunrise without the aid of face paint.

Overnight, the Papers had turned the extraordinary ordinary. And if there was one thing Sofi Ollenholt refused to be, it was ordinary.

The implication that she was using magic in her music was also damning. Musiks were musicians who lived, composed, and performed without the assistance of magic—Paper or otherwise. Any student hoping to ascend to the rank of Apprentice had to keep their hands clean and their art pure.

Even the rumor of a musician using magic was enough to destroy their career entirely—and hers hadn’t even begun.

Sofi shook away the memory of the interaction. Neha had always been jealous of Sofi’s innate ability, her natural talent. Sofi would not let the other girl’s baseless accusations get to her. She had never even touched a Paper, so strongly did she eschew magic, so hard did she work to keep herself clean. Deserving. Worthy of one day becoming a Musik herself.

Sofi grabbed her lute from its place on her pillow and brushed the strings lightly, patiently adjusting the tuning pegs. Aell’s perpetual cold meant her strings tended to tense, and if she wasn’t tender with them, the catgut would snap. The body of her lute pressed gently against her stomach, held in place by the crook of her right arm. That hand plucked the strings while her left hand fingered the notes up and down the instrument’s neck.

That shiver returned, the hair on her arms standing at attention as Sofi coaxed sound from her instrument, notes ringing out soft and sincere in her small room. While sometimes the more familiar pieces of her training routine felt tedious, this part never got old: the playing. Piecing her words and her melodies together. Using her hands and her voice and her mind to create something entirely new, something that would not exist were it not for her.

When Sofi played, she had power.

“Did bright Brielle put forth the snow, from where death’s sweaty hand would go,” Sofi sang, her left ring finger pressed tight upon the two strings of her lute’s fourth course. “The devil’s hot, candescent glow did urge her boldly on.”

Sofi played her way through the story of Saint Brielle, the woman who ended the devil’s scorching summer nearly two centuries ago. As Sofi sang her praise for the saint who commanded winter’s wind, the snow outside her bedroom window turned to sleet, hammering against the glass and displacing the crow that had been roosting beneath the slats of the roof. Ice collected in the window’s corners as the view of the snowcapped trees was blurred by wretched, unending white. Sofi sighed bitterly, her fingers falling from her instrument.

Lingering seasons weren’t uncommon in Aell. The Saint’s Summer, when Saint Evaline brought forth the harvest from the icy ground, had come after six years of cold. Saint Brielle’s winter ended ten agonizing years of summer. But Aell’s current winter was pushing seventeen years, longer than any in the history books or the epic tales sung by Musiks.

Sixteen years of snow. A season as old as Sofi.

The cold was all she’d ever known.

She pressed a hand to the frigid windowpane above her desk. Heat from her fingertips leached onto the glass, leaving marks that disappeared almost instantly. Sofi was afraid of fading away that easily, of leaving not a single visible mark on the world.

It was why she worked so hard. Played so often. Practiced so frequently. Why she obeyed her father’s orders and followed the training routine he’d set for her. So many years after its creation, it now held the monotonous familiarity of a lullaby: The first day was for listening, the second for wanting, the third for praying, the fourth for feeling, and the fifth for repenting. But sixth days were special.

Sixth days were for music.

It was a routine more extreme than the methods required of her father’s other students. But that was by choice. Sofi had always been willing to work harder. Push herself further. She would do whatever it took to become her father’s Apprentice and finally be able to perform publicly. Without the Apprentice title, musicians could only play and compose within their own homes. Sofi was far too talented for her songs to be confined within the four walls of her bedroom.

She placed her fingers back on the lute’s strings, picking the song up from its second chorus.

“That’s new.”

Sofi yelped, nearly falling off her chair as Jakko, her best friend and her father’s only live-in student, smiled at her from the doorway, his glossy black curls tumbling dramatically into his eyes.

“What are you doing in here?” Sofi settled her lute carefully back into its case. “The king’s downstairs. Shouldn’t you be groveling?”

Jakko sighed dramatically and flung himself onto her bed, hugging a pillow to his chest. “Jasper didn’t come this time. What’s the point of making an appearance if the prince can’t see me?”

Sofi rolled her eyes as she swept the papers littering her desk into a haphazard pile. “I still think that the alliteration is a little showy, even for you.” She threw her bare foot onto the mattress, nudging Jakko’s side. “I mean, Jasper and Jakko?” She wrinkled her nose in mock distaste. Jakko reached out a hand to tickle her, his golden-brown fingers warm against her toes. She kicked his hand away playfully.

“What are you wearing tonight?” Sofi cast a glance at the dress form that held her ruby-red gown for that evening’s performance. Most days she opted for shapeless, gray wool shifts. Function rather than form. It was a shock each time her father performed publicly: the jewel-toned dresses that appeared in her bedroom; the paint Marie, their housekeeper, would smear on her lips and cheeks; the way Sofi was flaunted about. That public display of self was a different sort of performance entirely.

“Well”—Jakko ran a hand through his curls—“now that Jasper’s not here, I have half a mind not to attend the performance at all.”

“You are,” Sofi laughed, “the least devoted student my father has ever had.”

“Untrue,” Jakko volleyed back. “Remember Thea?”

Sofi put a hand to her heart in mock pain. “Low blow.” Thea had been Sofi’s first crush. Luckily, there had never been any awkwardness or competition between the two of them because Thea was so useless at the lute that Sofi’s father had refused to teach her any further after only three lessons.

Frederik Ollenholt had quite a lot of what he called “artistic integrity” and what other people called “impossible standards.”

“All my blows are low.” Jakko wagged a finger at her. “I should’ve been a flautist.”

Sofi snorted. “You should have. There wasn’t any competition for that Apprenticeship. The only musician that showed up to audition was Therolious Ambor’s own son, Barton.” She made a face her best friend didn’t return. Jakko had suddenly become very interested in her duvet cover.

“What’s wrong?” Sofi moved onto the bed, sticking a finger under Jakko’s chin and tilting it up, forcing him to meet her eyes.

“I’m almost eighteen, Sof.” His voice was soft like a swaying breeze. “If your father doesn’t take his Apprentice in the next few months, I’ve got nothing.” His eyes flitted away from hers again.

“And?” Sofi prompted, even as her stomach squirmed guiltily. She knew Jakko well enough to know when he had more to say.

“And…,” he started, looking pained. “If he chooses me, what does that mean for you?”

It was Sofi’s turn to look away.

While anyone could—for the right price—take lessons from a Musik, the position of a Musik’s Apprentice was both highly coveted and highly competitive. Each Musik took on only one Apprentice in their lifetime. That Apprentice was granted their mentor’s treble clef pin, which allowed them to inherit the title of Musik when the reigning Musik retired or passed on. If Sofi wasn’t chosen as her father’s Apprentice, she would lose the chance of ever becoming a Musik, and the talent she had spent her life honing would become nothing more meaningful than a party trick. Without the title of Musik, Sofi would never make her mark on the world.

“I’d figure something out.” But Sofi’s lie fell flat. There was no other option.

Not for her.

Not every musician had the willpower or discipline to become a Musik. But Sofi, with a dead mother and a father who spent most of his life on the road, had nothing but time. She had dedicated her entire life to ensuring the Muse was on her side. She had been handed a lute at four years old and could read music before she could write her own name. She whiled away hours studying theory, poring over lyrics and rhyme schemes. By the age of eight, she was performing works that tripped up her father’s most seasoned students. Once, when she was ten, she taught herself to play a song holding her lute upside down, just to prove that she could.

But beyond her hard work and dedication, and perhaps most importantly, Sofi was good. Her technical skill was unparalleled; she could play even the most complex melodies after hearing them only once. Sofi was so focused on perfection that any mistake she made—missing a note or striking an errant string, falling out of time or taking a beat too long to make a transition—became a learning experience, an obsession, the same phrase played over and over until she was certain she would never waver again. Even her father, with his signature scrutiny and painfully expressive features, found less and less to criticize as the years went on.

Sofi adored Jakko. He was a good lutenist and an even better friend. But the title of Apprentice would one day be hers.

It had to be.

“Liar.” But Jakko’s voice held no anger, only familiar resignation. He rolled onto his stomach, cheek pressed against her pillow. “Do you ever wish we loved an art that wasn’t so competitive? One that allowed us to use Papers?”

Sofi made a face, thinking of Neha. “Of course not.” She flopped over, nuzzling up next to Jakko. “Anyone can use a Paper to pen a poem about the queen or paint a picture of the king and call themselves an artist. But we create freely, with clean hands and talent alone.”

She offered her hand to Jakko, who pushed her unmarked skin away with a roll of his eyes. There was never any speculation as to which spell a Paper-caster had chosen to employ. Heartbreak, a hand would read, if a poet used a Paper to conjure the feeling necessary to write a poem of longing and loss. Flame, it would warn, if the caster needed fire. It was not uncommon to see Paper-casters whose hands were covered with so many words they appeared to be wearing gloves.

When the Paper’s power faded, so too would the word. The hand that had once flawlessly sketched the face of a king would go back to barely being able to draw a straight line. The fire that had been conjured would begin to dim. If an artist wanted to finish their sketch, if an innkeeper wanted to restoke the flames, first they would need to purchase another Paper.

Sofi shrugged. “What can I say? I love feeling superior.”

Jakko pushed himself up onto his elbows and frowned. “Do you love to feel superior or do you love to suffer? Because, Sofi, those bruises look nasty.”

Sofi swiftly rearranged her skirt to cover her knees. “I do what I have to for my art.” Her voice was hard.

“Of course.” Jakko’s tone was too casual. “Still, don’t you find it odd that your father never included anything like that in my training routine? No praying? No repenting?”

“I suppose,” Sofi said. But what she meant was no. Sofi had been practicing advanced training methods since she was a child. Methods her father’s other students weren’t privy to. Rather than making her feel isolated or alone, this distinction was further proof that becoming a Musik was her destiny.

Sofi reached for Jakko’s hand, twining her fingers in his. His palm was sweaty in that overheated-teenage-boy way. Jakko had been studying with Frederik since Sofi was thirteen and he fifteen. Three years later, they were practically inseparable, no dream too sincere, no competition cutthroat enough to keep them apart. It wouldn’t always be this way, but Sofi knew all too well what it was like to be alone. She would hold on as long as she could to his bright laughter, the way he lit up every room. The way he trusted her.

The way she almost trusted him.

“How come Marie never puts satin sheets on my bed?” Jakko rubbed his cheek theatrically across Sofi’s pillow.

“Because you steal her cheese.” Sofi giggled, squeezing his hand. She wished there were a way for them both to play music, together. That Jakko would not be relegated to nothingness when she was named her father’s successor.

Jakko made an affronted noise. “That’s true,” he finally conceded. “I do.”

“I knew it,” Sofi gasped, gripping Jakko’s wrist.

“Ow,” Jakko whined. “Your calluses are so rough.”

Sofi let go of him, waggling her fingers in his face. “I have the prettiest hands you’ve ever seen.”

“That’s not necessarily what I’d call them.” Jakko swatted at her, finally pushing himself up and off her bed. “Now, come on, Lady Ollenholt.” He offered her his hand. “Let’s go greet the king.”

By the time Sofi and Jakko arrived in the parlor, the pastries had been reduced to crumbs and the tea had gone cold. Marie tutted beneath her breath as she met them in the doorway. The housekeeper reached up to tuck one of Sofi’s unruly brown curls tenderly behind her ear.

“There you are.” Frederik’s expression was pinched despite the light bravado of his voice.

“Jakko. Sofi.” King Jovan’s voice was a deep bass that resonated warmly within his chest. He got to his feet, unmistakably royal, his brown skin flawlessly smooth, his beard closely cropped, his clothes perfectly tailored, his penchant for gold striking against his warm complexion and his glittering brown eyes. “Give your king a hug, then.” He opened his arms to Sofi, looking for all the world more fatherly than Frederik.

Sofi moved to him, inhaling the scent of sap and pine and the sweet sharp slice of perfume. Her father wasn’t a hugger, and Marie, despite her mothering tendencies, preferred to fuss rather than to envelop. It was not lost on Sofi how absurd it was that the most consistent embraces she received were from the king of her country.

“How are you, Your Majesty?” Sofi asked as they broke apart. Up close, there were shadows beneath his eyes.

“I look a sight, don’t I?” the king asked humorlessly. “I’ve just come from a meeting of the Council of Regents. Twenty years a king, yet I’m still paying for the sins of my father.”

Sofi’s brow furrowed sympathetically. The Papers commissioned by Jovan’s father, King Ashe, had generated incredible wealth for their country. But that power had increased Ashe’s greed tenfold, and he’d soon set his sights beyond Aell to the countries who served the Hollow God. The Hollow God’s followers lived by the pillars of piety, simplicity, hard work, and suffering. Unregulated magic had no place in their world.

So King Ashe was careful to position the Papers as everything witches were not: careful, contained, and controllable. Yet once the deals were done, the new Papers he’d sold hadn’t worked as the originals had. This magic turned volatile and downright dangerous. Instead of a Paper that commanded water buckets to carry themselves, the Kingdom of Tique faced a slew of slimy newts that sent a sickness through the country’s waterways. Heinous burns cropped up on the faces of Dolgesh citizens who had used glamours to polish their appearances. And when the Queen of Roth’s personal chef used a Paper to speed up the simmering of a stew, the monarch found herself suddenly and violently ill.

The Council of Regents—made up of rulers from those neighboring monarchies—began to suspect that Ashe had been using the power of witches to expand his empire by weakening theirs. In retribution, they built the Gate, which closed their borders to all citizens of Aell, keeping Aellinians alone. Contained.

“Of course,” the king continued, his hand heavy on Sofi’s shoulder, “you wouldn’t know anything about that. I cannot wait for your father to transport us all with his performance tonight. I do believe the entire Guild will be in attendance.” His eyes fell tenderly on Frederik like a mother bird to a hatchling.

The five members of the Guild of Musiks were King Jovan’s peace offering to the Council of Regents—proof that Aell held no ill will against its neighbors. That its citizens could create even when their hands were clean of magic. The instruments of the Guild—lute, lyre, drum, flute, and accordion—were the only ones allowed to be played in public. Musiks were the only Aellinians allowed through the Gate.

King Jovan had high hopes that it would be the Guild who would ultimately convince the Council to reopen the border and let Aell rejoin the world.

“Yes,” the king continued, “it’s shaping up to be a most exciting evening.”

Sofi could feel Jakko’s eyes on the back of her neck. These days, gathering the entire Guild in one room was a feat. When Sofi was younger, she had accompanied Frederik to many a performance, traveling by coach to towns all across Aell to see his fellow Musiks perform in gilded theaters. But those performances had been fewer and farther between as of late.

Tonight was already a significant occasion. But as the king’s eyes glittered mischievously, reflecting the roaring fire in the hearth behind him, it was clear something greater was afoot.

“Certainly, Your Majesty,” Sofi agreed, curiosity mounting. “A most exciting evening indeed.”

Descriere

A gorgeous, queer standalone fantasy by the author of Sweet & Bitter Magic, following a young musician who sets out to expose her rival for illegal use of magic only to discover the deception goes deeper than she could have imagined.