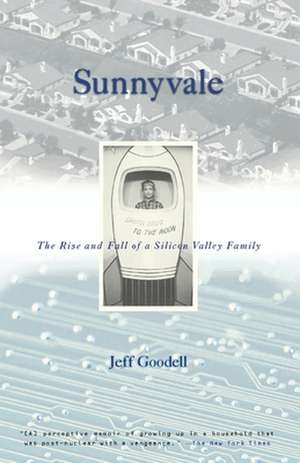

Sunnyvale: The Rise and Fall of a Silicon Valley Family

Autor Jeff Goodellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2001

Splintered by their parent's divorce, Jeff and his siblings careen toward self-destruction, while their parents end up on opposite sides of the technological divide: their mother succeeds beyond her wildest dreams at "a small company with a dopey rainbow-colored logo," called Apple, while their father refuses to keep up with the times and loses his landscaping business. Affecting and personal, Sunnyvale is a portrait of one family's fate in a brutally Darwinian world. It is also a thoughtful examination of what has happened to the American family in the face of the technological revolution.

Preț: 90.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.39€ • 18.05$ • 14.50£

17.39€ • 18.05$ • 14.50£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679776383

ISBN-10: 0679776389

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0679776389

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

Jeff Goodell is the author of The Cyberthief and the Samurai. He is a contributing editor at Rolling Stone, and his work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, Wired, and GQ. A fourth-generation Californian, he now lives in upstate New York. He can be e-mailed at jg@well.com.

Extras

Chapter 1

As a kid, I always felt lucky. I had a mother, a father, a brother, a sister, four grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, two dogs, a surly cat named Princess, and a brand-new house in a brand-new world. Even the name of the town I lived in made me feel lucky: Sunnyvale.

I loved the word Sunnyvale. It was different from the names of towns around us-like San Jose and Palo Alto and San Francisco, which had a dreamy, old Spanish romance about them. And it was not a name like Silicon Valley, which Sunnyvale was right in the middle of, but which always made me think of breasts and robots. The word Sunnyvale had utopian flair. It suggested to me that I lived in a special place-a world of sunshine and progress, of new gizmos and old fruit trees, where life promised to be a rocket ride across friendly skies. Streets were named after birds and flowers, and I could walk all the way to school on beautifully curving sidewalks, and my fourth-grade class took field trips to buildings where people smashed atoms and built satellites. How could I not feel lucky? I lived in a place where, as my mother often counseled me after a hard day, "Everything will work out okay."

And for a long time, I believed her. The pictures on the TV news of bloody American soldiers being lifted into helicopters, the resignation of the president, the death of Elvis-none of that rocked me. Then one morning in the spring of 1979, my mother said firmly, "I have something I need to talk to you and your brother and sister about. Let's go sit down." I knew by the disturbingly unsunny look on her face that this was a serious matter. We tromped single-file into the family room.

I was nineteen at the time, the oldest of three kids in my family. Like most other seventies teenagers with social aspirations, I wore a puffy down jacket on even the mildest days and had let my hair grow out long enough that I could chew on my bangs. I wasn't a stoner, but I smoked dope at parties, especially if the party was at my friend Rod's house, where the nights often ended with Dark Side of the Moon blasting and everyone taking off their clothes and jumping into the pool. My brother, Jerry, was twenty-two months younger than me, a senior in high school with sun-bleached blond hair and a soft, gentle face that featured none of my adolescent cockiness. My sister, Jill, had just turned eleven and was a hazel-eyed girl whose bedroom was covered with posters of the Bay City Rollers.

My mother sat on the edge of our green plaid sofa. On good days, she looked a little like Liz Taylor without the movie-star glitz: dark hair, soft round face, a hint of tragedy in every smile. On bad days, like this one, her face looked like a thundercloud that was ready to burst from pent-up emotion.

As we waited for her to speak, the word cancer flashed in my mind. I'd been obsessed with the word lately. I often checked my body for lumps and lay in bed at night imagining tumors coiling through my body, their tentacles rooting into my liver and kidneys. Now I wondered whether these nightmares had been premonitions and our mother was about to tell us she was going to die. In that split second, I was already asking myself, "Why her?" I loved my mother. Not only that, she was an extremely cool person. She had been only nineteen when I was born-she felt practically like my older sister. She listened to Creedence and the Allman Brothers just like I did, danced with my friends at my parties, and never blew a gasket when she found an empty beer can in the backyard. Lately, she had been kicking up her heels a bit. She had frizzed her hair, started wearing paisley blouses and big beaded necklaces, and decided, for the first time in her adult life, that she wanted to get a job. In a town like Sunnyvale, which was stocked with engineers and their obedient wives, this was a revolutionary act. My mother had talked to a neighbor who was an executive at a data-storage company, and before long she was working in the file room.

My father was not thrilled. He liked the idea of my mother staying at home with us kids. For her to be off, working in an office at a big company that built computer stuff, just seemed wrong to him. He worried that people would think he could not provide for his family on his own.

My father's name was Ray. When I was a kid, I thought he was a big, noble man, my own Paul Bunyan. He was six foot two, with callused hands and a worn, slender, handsome face, dazzling green-gold eyes, and light brown hair that was so fine it danced with the slightest stirring of air-a closing door, a cough. He worked in the landscape-contracting business, building city parks and beautifying highways around the Valley, and was happiest when he had dirt under his fingernails. He loved to hunt and fish and tried to pass his love of the outdoors on to me. He taught me how to shoot a rifle and split kindling wood and thread a worm onto a hook. More than anything else, he loved to build things. He turned our garage into a family room, moved the location of the front door, built a carport, a workshop, a laundry room, and benches in the backyard. I could always tell when things weren't going well at work or when he was troubled by something at home, because that was when he started a new project. Pounding nails was his form of psychotherapy.

Of all his projects, however, the fireplace in the family room was the one he was most proud of. It was a massive brick and stone structure, more appropriate for a castle in the English countryside than a flimsy tract home in Sunnyvale, where the temperature rarely dipped below forty degrees. The firebox was large enough to roast an ox and sat on a two-foot-high hearth made of old cobblestones he'd dug up on a job in San Francisco. My father had laid every brick and stone himself, buttering them with mortar, stringing them along a plumb line. It had taken him months of weekends and evenings to complete and required a devotion that was as much spiritual as physical. Over the years, the fireplace radiated that devotion back to us in heat and light. It became our family totem pole, our mosh pit, our sacred site. It was where we opened our Christmas presents and sang "Happy Birthday to You" and talked about love and the threat of nuclear war.

Now I stared at those same bricks and stones, suddenly terrified of the bomb my mother was about to drop.

"Your father and I have decided to get a divorce," she said plainly and without tears.

Divorce! I exhaled, relieved. Unlike cancer, this was a word I could handle.

To me, divorce felt more like a step into the modern world than a breaking of a sacred covenant. In the late 1970s, it seemed like everybody we knew was splitting up-it was the romantic equivalent of the Pet Rock craze. My uncle Bob, who wore leather sandals from Tijuana and told jokes about traveling salesmen who got the clap, had ended his marriage with his go-go boot-wearing wife, Sheila, and taken up with a series of flashy women. My best friend's father, a building contractor who kept tightly rolled joints in the ashtray of his van, ran off with a dental hygienist. Even my uncle Dick, a straitlaced mid-level manager at Hewlett-Packard, split with his wife and took up with a succession of free-spirited female companions.

My mother did her best to make the divorce seem like a rational and sensible decision. She told us that it was no reflection of her feelings for us, that she and my father still loved us deeply, and that they would both continue to be parts of our lives.

Jill was the only one of us who showed any emotion: Her eyes welled up, and she ran out of the room. My mother followed her.

I looked over at Jerry.

"You okay?" I asked.

"Yeah, I'm fine."

We stared at the wall for a moment.

"This is no big deal," I said.

"Yeah," he said.

"It doesn't mean anything."

"I know."

Then Jerry went into his bedroom and put on a Van Halen album and that was the end of it.

Or so I thought. At some point, as I sat there in the family room, staring at those massive hearthstones, it dawned on me that there had been only four people present for the announcement, not five: Where was our father? He prided himself on always being there for his kids, no matter what. I couldn't believe he would dodge an important moment like this.

But he had. Later, my mother explained to me that my father was too torn up to face us and thought it'd be better for everyone if he wasn't around when she broke the news. I was not sympathetic. In fact, I thought it was cowardly.

When my father turned up the next day-he just pulled into the driveway in his white Chevy El Camino as if he'd run to the store for a carton of milk-he tried to act like it was no big deal, but even I could see how busted up he was inside. For a family man like my father, a man who had put all his eggs in one basket, so to speak, and carried that basket around for twenty years, this was the worst thing that could have happened to him. So he pretended it wasn't happening. He told us that he and my mother were "separating," but that he hoped things would work out. I nodded and shrugged and avoided looking him in the eye, afraid of what I might see. I couldn't believe that the man who often held me responsible for my actions was dodging responsibility for his own.

A few weeks later, Jerry and I took off on a trip to Europe that we'd planned for months. On the flight to London, Jerry and I hardly talked about the divorce. I think he believed that when he returned home, our mother and father would have worked it out and everything would be back to normal. I knew that wouldn't be the case. I knew it was over, but I didn't care. I thought breaking up a family was like breaking up with a girlfriend: There would be a few months of mooning and heavy hearts, then we'd move on.

Jerry got homesick and flew back after about four weeks in Europe. I stayed four months, rattling around with my backpack and Eurail Pass. I'd planned to go to India, but the farthest east I got was Istanbul; overland travel across Iran was extremely dangerous for Americans at the time, and I was too poor to fly. Instead, I spent a month crawling around ancient ruins on the Turkish coast. At a café in Marmaris, I ordered a peculiar-looking dish that I thought was roasted eggplant but might well have been decomposing eggplant, contracted dysentery, and headed home.

When I returned, I was greeted with a surreal sight: The family portrait was just as it had been when I'd left-big house, big fireplace, two dogs, my mother cooking dinner, Jill and Jerry battling over the TV-except my father had been airbrushed out of the picture.

vvvv

Years later, I learned that when my mother had told my father she wanted to split up, his initial reaction had been disbelief. After all, he had just finished building a new upstairs addition, including a spacious bedroom suite. (It was a typically well-intentioned but clueless gesture, as if there were no problems in their marriage that a bigger master bath wouldn't fix.) He accused my mother of sabotaging their marriage and stealing his family from him, but his anger was brief and shallow because he knew it wasn't true. They were splitting up not because she had fallen in love with someone else but because she was bored. As my mother told me years later, "I wanted to dance." She meant that literally and metaphorically, and my father knew it. At one point, he fell to his knees and promised my mother that if she stayed, he would jazz up their lives; as proof, he offered to take her to Tahiti for a week. She declined.

Finally, my father decided that the best thing to do was give my mother some space. So while Jerry and I were in Europe, he moved into a two-bedroom condo in Cupertino. He believed his departure was only temporary-a matter of a few months, maybe-before my mother came back around. The condo was bike-riding distance from our house in Sunnyvale, but it was a different world-a lonely and anonymous place with a small kitchen window that looked out over a concrete side yard, and dark bedrooms with shag carpet and flimsy doors. It had no fireplace, just forced-air heating.

I was in no rush to visit my father after I returned from my trip. A week passed, then another; finally my mother practically begged me to stop by and see him. Out of respect more for her than for him, I agreed.

When I arrived, my father's eyes lit up. He invited me in, and we sat at the small rectangular table in the kitchen and drank instant coffee. He was still a young man-he'd just turned forty-three-but he looked as if he'd aged ten years in the four months since I'd seen him last. He was a person who thrived on fresh air and sunlight; in the condo, he lived like a caged bear. His shoulders were always brushing against walls, his eyes drifting toward the window, searching for soft, green space and finding only cyclone fence, concrete, and telephone wires.

"So you had a good time in Europe?" he asked.

I nodded and gave him a quick review of my trip-the Eiffel Tower, the midnight sun in Norway, the Alps. Recounting this for my father was all the sweeter because I owed him nothing for it-I'd paid for the trip myself, out of money I'd earned doing odd jobs. My father listened, slurped coffee, nodded. He didn't care about my trip. He cared that I was there, sitting across from him at his kitchen table, telling him about it.

When I finished, my father picked at a callus on his palm. I could see he was working himself up to something. Finally, he said, "What's new with your mother?"

As a kid, I always felt lucky. I had a mother, a father, a brother, a sister, four grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, two dogs, a surly cat named Princess, and a brand-new house in a brand-new world. Even the name of the town I lived in made me feel lucky: Sunnyvale.

I loved the word Sunnyvale. It was different from the names of towns around us-like San Jose and Palo Alto and San Francisco, which had a dreamy, old Spanish romance about them. And it was not a name like Silicon Valley, which Sunnyvale was right in the middle of, but which always made me think of breasts and robots. The word Sunnyvale had utopian flair. It suggested to me that I lived in a special place-a world of sunshine and progress, of new gizmos and old fruit trees, where life promised to be a rocket ride across friendly skies. Streets were named after birds and flowers, and I could walk all the way to school on beautifully curving sidewalks, and my fourth-grade class took field trips to buildings where people smashed atoms and built satellites. How could I not feel lucky? I lived in a place where, as my mother often counseled me after a hard day, "Everything will work out okay."

And for a long time, I believed her. The pictures on the TV news of bloody American soldiers being lifted into helicopters, the resignation of the president, the death of Elvis-none of that rocked me. Then one morning in the spring of 1979, my mother said firmly, "I have something I need to talk to you and your brother and sister about. Let's go sit down." I knew by the disturbingly unsunny look on her face that this was a serious matter. We tromped single-file into the family room.

I was nineteen at the time, the oldest of three kids in my family. Like most other seventies teenagers with social aspirations, I wore a puffy down jacket on even the mildest days and had let my hair grow out long enough that I could chew on my bangs. I wasn't a stoner, but I smoked dope at parties, especially if the party was at my friend Rod's house, where the nights often ended with Dark Side of the Moon blasting and everyone taking off their clothes and jumping into the pool. My brother, Jerry, was twenty-two months younger than me, a senior in high school with sun-bleached blond hair and a soft, gentle face that featured none of my adolescent cockiness. My sister, Jill, had just turned eleven and was a hazel-eyed girl whose bedroom was covered with posters of the Bay City Rollers.

My mother sat on the edge of our green plaid sofa. On good days, she looked a little like Liz Taylor without the movie-star glitz: dark hair, soft round face, a hint of tragedy in every smile. On bad days, like this one, her face looked like a thundercloud that was ready to burst from pent-up emotion.

As we waited for her to speak, the word cancer flashed in my mind. I'd been obsessed with the word lately. I often checked my body for lumps and lay in bed at night imagining tumors coiling through my body, their tentacles rooting into my liver and kidneys. Now I wondered whether these nightmares had been premonitions and our mother was about to tell us she was going to die. In that split second, I was already asking myself, "Why her?" I loved my mother. Not only that, she was an extremely cool person. She had been only nineteen when I was born-she felt practically like my older sister. She listened to Creedence and the Allman Brothers just like I did, danced with my friends at my parties, and never blew a gasket when she found an empty beer can in the backyard. Lately, she had been kicking up her heels a bit. She had frizzed her hair, started wearing paisley blouses and big beaded necklaces, and decided, for the first time in her adult life, that she wanted to get a job. In a town like Sunnyvale, which was stocked with engineers and their obedient wives, this was a revolutionary act. My mother had talked to a neighbor who was an executive at a data-storage company, and before long she was working in the file room.

My father was not thrilled. He liked the idea of my mother staying at home with us kids. For her to be off, working in an office at a big company that built computer stuff, just seemed wrong to him. He worried that people would think he could not provide for his family on his own.

My father's name was Ray. When I was a kid, I thought he was a big, noble man, my own Paul Bunyan. He was six foot two, with callused hands and a worn, slender, handsome face, dazzling green-gold eyes, and light brown hair that was so fine it danced with the slightest stirring of air-a closing door, a cough. He worked in the landscape-contracting business, building city parks and beautifying highways around the Valley, and was happiest when he had dirt under his fingernails. He loved to hunt and fish and tried to pass his love of the outdoors on to me. He taught me how to shoot a rifle and split kindling wood and thread a worm onto a hook. More than anything else, he loved to build things. He turned our garage into a family room, moved the location of the front door, built a carport, a workshop, a laundry room, and benches in the backyard. I could always tell when things weren't going well at work or when he was troubled by something at home, because that was when he started a new project. Pounding nails was his form of psychotherapy.

Of all his projects, however, the fireplace in the family room was the one he was most proud of. It was a massive brick and stone structure, more appropriate for a castle in the English countryside than a flimsy tract home in Sunnyvale, where the temperature rarely dipped below forty degrees. The firebox was large enough to roast an ox and sat on a two-foot-high hearth made of old cobblestones he'd dug up on a job in San Francisco. My father had laid every brick and stone himself, buttering them with mortar, stringing them along a plumb line. It had taken him months of weekends and evenings to complete and required a devotion that was as much spiritual as physical. Over the years, the fireplace radiated that devotion back to us in heat and light. It became our family totem pole, our mosh pit, our sacred site. It was where we opened our Christmas presents and sang "Happy Birthday to You" and talked about love and the threat of nuclear war.

Now I stared at those same bricks and stones, suddenly terrified of the bomb my mother was about to drop.

"Your father and I have decided to get a divorce," she said plainly and without tears.

Divorce! I exhaled, relieved. Unlike cancer, this was a word I could handle.

To me, divorce felt more like a step into the modern world than a breaking of a sacred covenant. In the late 1970s, it seemed like everybody we knew was splitting up-it was the romantic equivalent of the Pet Rock craze. My uncle Bob, who wore leather sandals from Tijuana and told jokes about traveling salesmen who got the clap, had ended his marriage with his go-go boot-wearing wife, Sheila, and taken up with a series of flashy women. My best friend's father, a building contractor who kept tightly rolled joints in the ashtray of his van, ran off with a dental hygienist. Even my uncle Dick, a straitlaced mid-level manager at Hewlett-Packard, split with his wife and took up with a succession of free-spirited female companions.

My mother did her best to make the divorce seem like a rational and sensible decision. She told us that it was no reflection of her feelings for us, that she and my father still loved us deeply, and that they would both continue to be parts of our lives.

Jill was the only one of us who showed any emotion: Her eyes welled up, and she ran out of the room. My mother followed her.

I looked over at Jerry.

"You okay?" I asked.

"Yeah, I'm fine."

We stared at the wall for a moment.

"This is no big deal," I said.

"Yeah," he said.

"It doesn't mean anything."

"I know."

Then Jerry went into his bedroom and put on a Van Halen album and that was the end of it.

Or so I thought. At some point, as I sat there in the family room, staring at those massive hearthstones, it dawned on me that there had been only four people present for the announcement, not five: Where was our father? He prided himself on always being there for his kids, no matter what. I couldn't believe he would dodge an important moment like this.

But he had. Later, my mother explained to me that my father was too torn up to face us and thought it'd be better for everyone if he wasn't around when she broke the news. I was not sympathetic. In fact, I thought it was cowardly.

When my father turned up the next day-he just pulled into the driveway in his white Chevy El Camino as if he'd run to the store for a carton of milk-he tried to act like it was no big deal, but even I could see how busted up he was inside. For a family man like my father, a man who had put all his eggs in one basket, so to speak, and carried that basket around for twenty years, this was the worst thing that could have happened to him. So he pretended it wasn't happening. He told us that he and my mother were "separating," but that he hoped things would work out. I nodded and shrugged and avoided looking him in the eye, afraid of what I might see. I couldn't believe that the man who often held me responsible for my actions was dodging responsibility for his own.

A few weeks later, Jerry and I took off on a trip to Europe that we'd planned for months. On the flight to London, Jerry and I hardly talked about the divorce. I think he believed that when he returned home, our mother and father would have worked it out and everything would be back to normal. I knew that wouldn't be the case. I knew it was over, but I didn't care. I thought breaking up a family was like breaking up with a girlfriend: There would be a few months of mooning and heavy hearts, then we'd move on.

Jerry got homesick and flew back after about four weeks in Europe. I stayed four months, rattling around with my backpack and Eurail Pass. I'd planned to go to India, but the farthest east I got was Istanbul; overland travel across Iran was extremely dangerous for Americans at the time, and I was too poor to fly. Instead, I spent a month crawling around ancient ruins on the Turkish coast. At a café in Marmaris, I ordered a peculiar-looking dish that I thought was roasted eggplant but might well have been decomposing eggplant, contracted dysentery, and headed home.

When I returned, I was greeted with a surreal sight: The family portrait was just as it had been when I'd left-big house, big fireplace, two dogs, my mother cooking dinner, Jill and Jerry battling over the TV-except my father had been airbrushed out of the picture.

vvvv

Years later, I learned that when my mother had told my father she wanted to split up, his initial reaction had been disbelief. After all, he had just finished building a new upstairs addition, including a spacious bedroom suite. (It was a typically well-intentioned but clueless gesture, as if there were no problems in their marriage that a bigger master bath wouldn't fix.) He accused my mother of sabotaging their marriage and stealing his family from him, but his anger was brief and shallow because he knew it wasn't true. They were splitting up not because she had fallen in love with someone else but because she was bored. As my mother told me years later, "I wanted to dance." She meant that literally and metaphorically, and my father knew it. At one point, he fell to his knees and promised my mother that if she stayed, he would jazz up their lives; as proof, he offered to take her to Tahiti for a week. She declined.

Finally, my father decided that the best thing to do was give my mother some space. So while Jerry and I were in Europe, he moved into a two-bedroom condo in Cupertino. He believed his departure was only temporary-a matter of a few months, maybe-before my mother came back around. The condo was bike-riding distance from our house in Sunnyvale, but it was a different world-a lonely and anonymous place with a small kitchen window that looked out over a concrete side yard, and dark bedrooms with shag carpet and flimsy doors. It had no fireplace, just forced-air heating.

I was in no rush to visit my father after I returned from my trip. A week passed, then another; finally my mother practically begged me to stop by and see him. Out of respect more for her than for him, I agreed.

When I arrived, my father's eyes lit up. He invited me in, and we sat at the small rectangular table in the kitchen and drank instant coffee. He was still a young man-he'd just turned forty-three-but he looked as if he'd aged ten years in the four months since I'd seen him last. He was a person who thrived on fresh air and sunlight; in the condo, he lived like a caged bear. His shoulders were always brushing against walls, his eyes drifting toward the window, searching for soft, green space and finding only cyclone fence, concrete, and telephone wires.

"So you had a good time in Europe?" he asked.

I nodded and gave him a quick review of my trip-the Eiffel Tower, the midnight sun in Norway, the Alps. Recounting this for my father was all the sweeter because I owed him nothing for it-I'd paid for the trip myself, out of money I'd earned doing odd jobs. My father listened, slurped coffee, nodded. He didn't care about my trip. He cared that I was there, sitting across from him at his kitchen table, telling him about it.

When I finished, my father picked at a callus on his palm. I could see he was working himself up to something. Finally, he said, "What's new with your mother?"

Recenzii

“A perceptive memoir of growing up in a household that was post-nuclear with a vengeance.”–The New York Times

“Mesmerizing and deeply authentic.... Compelling.”–San Jose Mercury News

“Reflects the seismic social changes that still shake American society.”–USA Today

“Mesmerizing and deeply authentic.... Compelling.”–San Jose Mercury News

“Reflects the seismic social changes that still shake American society.”–USA Today

Descriere

In Sunnyvale, California, in 1979, Goodell's family lived quietly, unaware that their town was soon to become ground zero in the digital revolution. Affecting and personal, his autobiography is a portrait of one family's fate in a brutally Darwinian world.