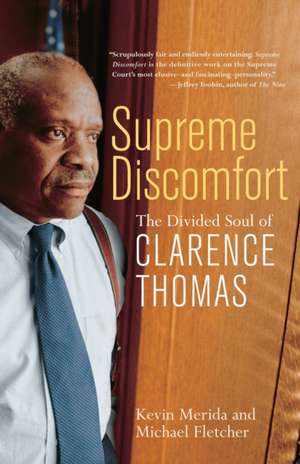

Supreme Discomfort: The Divided Soul of Clarence Thomas

Autor Kevin Merida, Michael Fletcheren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2008

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Supreme Discomfort is a superbly researched and reported work that features testimony from friends and foes alike who have never spoken in public about Thomas before—including a candid conversation with his fellow justice and ideological ally, Antonin Scalia. It offers a long-overdue window into a man who straddles two different worlds and is uneasy in both—and whose divided personality and conservative political philosophy will deeply influence American life for years to come.

Preț: 101.34 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 152

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.39€ • 20.17$ • 16.01£

19.39€ • 20.17$ • 16.01£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767916363

ISBN-10: 0767916360

Pagini: 426

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767916360

Pagini: 426

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

Advance Praise for Supreme Discomfort:

“Clarence Thomas, even as the quiet justice, is a clanging symbol of politics and race in our time. I can’t think of two writers I’d rather have cut through the cacophony of the Thomas mythology than Kevin Merida and Michael A. Fletcher. In Supreme Discomfort, they have found the divided soul that divides a nation.” —David Maraniss, author of First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton

“Scrupulously fair and endlessly entertaining. Supreme Discomfort by Kevin Merida and Michael A. Fletcher is the definitive work on the Supreme Court’s most elusive—and fascinating—personality.” —Jeffrey Toobin, author of The Run of His Life and Too Close to Call, legal affairs analyst for CNN, and staff writer at The New Yorker.

“An engrossing biography of a conflicted man . . . [Merida and Fletcher] have done a superb job with this both harsh and sympathetic life of Clarence Thomas . . . an unflinching look at success and race in America.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred)

“Clarence Thomas, even as the quiet justice, is a clanging symbol of politics and race in our time. I can’t think of two writers I’d rather have cut through the cacophony of the Thomas mythology than Kevin Merida and Michael A. Fletcher. In Supreme Discomfort, they have found the divided soul that divides a nation.” —David Maraniss, author of First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton

“Scrupulously fair and endlessly entertaining. Supreme Discomfort by Kevin Merida and Michael A. Fletcher is the definitive work on the Supreme Court’s most elusive—and fascinating—personality.” —Jeffrey Toobin, author of The Run of His Life and Too Close to Call, legal affairs analyst for CNN, and staff writer at The New Yorker.

“An engrossing biography of a conflicted man . . . [Merida and Fletcher] have done a superb job with this both harsh and sympathetic life of Clarence Thomas . . . an unflinching look at success and race in America.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred)

Notă biografică

KEVIN MERIDA is an associate editor at the Washington Post. He has been a national political reporter for the paper, a feature writer for its “Style” section, and a columnist for the Post’s Sunday magazine. In 2000 he was named Journalist of the Year by the National Association of Black Journalists. MICHAEL A. FLETCHER covers the White House for the Washington Post, where he has been a reporter since 1995. He has previously covered education and race relations, chronicling issues including the racial achievement gap, racial profiling, criminal justice disparities, and the battle over the future of affirmative action.

Extras

1

COURTING VENOM

Being Clarence Thomas

Dallas attorney Eric Moye received his copy in the mail from a fellow Harvard Law School alum. He started reading it but stopped to make a copy of the copy for a friend. He continued reading, absorbed, enchanted, depressed, exhilarated. Couldn’t put it down—except to make more copies.

It wasn’t a John Grisham thriller, but it might as well have been. “An Open Letter to Justice Clarence Thomas from a Federal Judicial Colleague” created an enormous buzz when the University of Pennsylvania Law Review published it in January 1992. Written by A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., chief judge emeritus of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, it was part history lesson and part admonition. Crafted with scholarly precision, it contained eighty–five footnotes and numerous citations of important court cases. But the essence of it read like a stern grandfather lecturing his bullheaded grandson: Don’t forget the roots of your success, boy, and the responsibilities you have to those who paved your way.

"You…must try to remember that the fundamental problems of the disadvantaged, women, minorities, and the powerless have not all been solved simply because you have ‘moved on up’ from Pin Point, Georgia, to the Supreme Court,” Higginbotham wrote in the conclusion of his twenty–four–page set of instructions to Thomas. Reciting a roster of notable names from the past, Higginbotham urged Thomas to see his life as connected to “the visions and struggles of Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Charles Hamilton Houston, A. Philip Randolph, Mary McLeod Bethune, W. E. B. Du Bois, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, Martin Luther King, Judge William Henry Hastie, Justices Thurgood Marshall, Earl Warren, and William Brennan, as well as the thousands of others who dedicated much of their lives to create the America that made your opportunities possible.”

The “open letter” read at times like a personal letter and was dated November 29, 1991, which was shortly after Thomas took his seat on the high court. Higginbotham felt ambivalent about making his letter public but did so, he said, to help this generation and future ones better evaluate Thomas. Because it was so well sourced and because it was penned by a black twenty–seven–year veteran of the federal bench, the letter as law review article carried an authority that most Thomas critiques did not.

As such, it received considerable attention. The University of Pennsylvania received more than seventeen thousand requests for reprints, and law offices around the country busily churned out photocopies.

“Sometimes chain letters circulate all over the place,” recalled Moye, “and this was kind of like one of those.” Nowhere was the interest greater than in black legal circles, where a robust debate was unfolding about what kind of justice Thomas would become. Moye, a former state district judge with a weakness for Cuban cigars and the finest steaks, acted as if he’d reached nirvana. After he made his first copy of the Higginbotham treatise and got his secretary to make five more copies, he bought the bound version to put on his office shelf. So many photocopies were in circulation that another one even came back to Moye—just like a chain letter.

“It was spreading like fire across the dry prairie,” Moye recalled. “Folks were calling one another speculating on whether Thomas would ever respond to Judge Higginbotham's open letter.”

The showdown marked the beginning of a transition in the way African Americans came to view Thomas, a shift that helped harden his image nationally. Gradually but inexorably, wariness supplanted wait–and–see as the predominant state of mind among blacks. Wariness became distrust, which blossomed into contempt.

“I'll put it like this,” said basketball legend Kareem Abdul Jabbar. “If he let people know that he was going to be at some public destination, let’s say in Harlem, at a certain hour on a certain day, let’s see how many supporters would show up and how many detractors would show up.” The National Basketball Association’s all–time leading scorer was another who had discovered Higginbotham’s law article and wondered: How can someone who benefited so richly from affirmative action not support the same remedy for those in similar circumstances?

Though his confirmation hearings left Thomas wounded and enraged, the good news should have been that initially, at least, more than twice as many African Americans, according to polls, believed him as believed Anita Hill. But Thomas couldn’t find the resolve to embrace that reassuring fact. He was shell–shocked by his ordeal and retreated into his work, which was difficult enough, and he was already behind. The court’s term began in October 1991. Because of his drawn–out confirmation process and the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s wife, Nan, Thomas wasn’t sworn in until the first day of November. He arrived with no staff, his law clerks weren’t up to speed, and he was hamstrung by his inexperience as a judge—he’d spent just nineteen months on the D.C. Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals. Plus he was bone tired.

Higginbotham was certainly no help. He became a more formidable nemesis, shedding the reproving grandpa role for the part of public castigator. In an attention–getting 1994 lecture at the Hastings College of Law in San Francisco, Higginbotham used his hour–long remarks to issue a stiff condemnation of Thomas’s jurisprudence. In one pointed comparison, he said he had studied every opinion written by Thomas and every one composed by his predecessor Marshall, and the difference between the two jurists was “the difference between zero and infinity.”

Then he dug the knife in even deeper.

“I have often pondered how it is that Justice Thomas, an African American, could be so insensitive to the plight of the powerless. Why is he no different, or probably worse, than many of the most conservative Supreme Court justices of this century? I can only think of one Supreme Court justice during this century who was worse than Justice Clarence Thomas: James McReynolds, a white supremacist who referred to blacks as ‘niggers.’ ”

Those in the packed auditorium couldn’t help but notice how emotional Higginbotham had become, his voice trembling, tears flowing. Removing his glasses, he wiped his eyes with a handkerchief. During Democratic presidencies, Higginbotham’s name often surfaced on short lists of potential Supreme Court nominees. But it never rose to the top. (In 1995, he would be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the closest thing a president can muster to a consolation prize.) The hard part was that Higginbotham was sixty–five and now retired, and not only had he been passed over for a position he had long coveted, he saw it snatched by a junior he felt had not earned it. Detractors attributed Higginbotham’s behavior to some combination of bitterness, jealousy, and a broken heart. But whatever his reasons, the blasts were effective. And the judgment that Thomas was the kind of black man no black person should admire mushroomed.

The catalog of Thomas–targeted insults is fat and brutal, and today the estrangement between the justice and broad swaths of his own people seems almost irreconcilable. Emerge, a since–departed African American–oriented news magazine owned by the country’s first black billionaire, Bob Johnson, twice parodied Thomas on its cover—once wearing an Aunt Jemima–style headscarf and another time as a lawn jockey. The editions were among the magazine’s best sellers. Ebony magazine, which annually publishes a list of the nation’s hundred most influential African Americans, routinely leaves Thomas off its tally. A former Kansas City mayor can make it, but not the nation’s only black Supreme Court justice?

Invitations for Thomas to speak are now carefully vetted. He has discovered that saying yes to an offer also could mean signing up for public humiliation: name–calling, pickets, boycotts. The mere announcement of a Thomas visit is apt to trigger a controversy. In the most famous such episode, the superintendent of the Prince George’s County, Maryland, school system disinvited Thomas from speaking at a middle school in 1996 after several black school board members complained and threatened protests. The school board overruled its schools' chief, and the show went on—demonstrations and all. (Later, a law clerk gave Thomas a placard that he proudly displayed in his chambers as a kind of combat medal. It read: “Banned in P.G. County.”)

Thomas has become more intimate with his opposition than he ever thought would be possible in the relatively isolated life of a Supreme Court justice. No venue is sacred. The Reverend Al Sharpton took his beef straight to Thomas’s home. He led four hundred demonstrators, who stepped off chartered buses, to a public road outside the justice's secluded suburban Virginia subdivision. There they denounced Thomas as a traitor. Nearly a decade later, Sharpton would campaign for president and continue his bashing of Thomas in a nationally televised debate, claiming, “He is my color, but he’s not my kind.” Even in academia, where philosophical debate is encouraged, five black University of North Carolina law professors boycotted a visit by Thomas in the spring of 2002.

Racial disillusionment is the common theme in all these demonstrations—not ideology, not politics, but the seething sense that one of the potential bright lights of the race has rejected his chance to shine. Otherwise, the black North Carolina professors would have howled about the appearances of Justice Antonin Scalia and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in preceding years. But they didn’t. As the professors wrote, explaining their position, in a nation “in which African Americans are disproportionately poor, undereducated, imprisoned and politically compromised, identity—racial identity—very clearly matters. Were that not the case, Justice Thomas, for all his claims to the contrary, could not have declared himself the victim of a ‘high–tech lynching’ during the heated opposition to his appointment to the Supreme Court.”

A special strain of animus seems reserved for Thomas. When the American Civil Liberties Union of Hawaii proposed inviting Thomas to a debate on affirmative action in 2003, black board member Eric Ferrer was furious. That would be tantamount to “inviting Hitler to come speak on the rights of Jews,” he fumed. Thomas didn’t accept the invitation, but Ferrer ended up resigning from the board over the mere fact that an invitation had been extended. “The appropriate word is venom,” said conservative media critic Brent Bozell, assessing what has happened to Thomas. “I would challenge you to find anyone on the left who has been the target of such a vitriolic character assassination campaign as has Clarence Thomas. I even challenge you to find anyone on the right who has. This man is in his own league.”

A league of his own, but one he has helped create, as far as Eric Moye is concerned. Moye, active in Democratic politics, was up for a federal appeals court judgeship during the Clinton administration. He still remembers some of Thomas’s harsh critiques of civil rights groups during his years as Ronald Reagan’s chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Thomas once told an interviewer that there was not a single area in which the NAACP was doing good work—“I can’t think of any”—and another time complained that all civil rights leaders do is “bitch, bitch, bitch, moan and moan, whine and whine.” Moye wonders if Thomas ever stops to think when he dons his robe: Where would I be if these civil rights figures had not carried the fight to statehouses and courthouses, had not taken the beatings, gone to jail, refused to wilt under exhausting oppression, and even been willing to die for equality? (Actually, Thomas has answered that question. He doesn’t credit civil rights leaders for his opportunities. “My grandfather—that’s the guy that got me out," he once told an interviewer. “It wasn’t all these people who are claiming all this leadership stuff.”)

As Moye sees it, Thomas has tilted so far away from his heritage that there is no longer any real debate about him. “I think there is a profound sense of despair,” Moye says. “In order to have disappointment you have to have high expectations. I think there were those who hoped he was going to blossom and develop. But I don’t think you know many African Americans, other than those who know him personally, who think he turned out all right.”

Comedians now use him as material. Rappers turn him into lyrics. This, from the song “Build and Destroy,” by KRS–One:

The white man ain’t the devil I promise

You want to see the devil take a look at Clarence Thomas.

Essayists have taken the Thomas–dissecting cottage industry to new heights. Michael Thelwell, an Afro–American studies scholar, writes: “Perhaps black people ought to give serious thought to retiring Clarence from general use as a name in our communities.”

This is what Moye was talking about—Thomas has become an infamous cultural symbol. The Notorious C.T.

In September 1997, Moye happened to be seated next to Judge Higginbotham at a Harvard Law School dinner at Legal Sea Foods in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At one point, still curious after all these years, Moye leaned over and asked if Higginbotham had ever received a private reply to his letter. No, the judge said, he hadn’t. It was the last time Moye would see Higginbotham.

Thomas was terribly bothered by Higginbotham’s criticism, he confided to friends, for it seemed to defy customary judicial decorum and was so unsparing. In 1998, Higginbotham opposed having Thomas speak to the National Bar Association convention in Memphis, saying it was like inviting George Wallace to dinner after he stood in the schoolhouse door and promised to maintain segregation forever. After the usual controversy over his appearance and much hand–wringing, Thomas did speak to the group. In remarks that veered from self–pitying to combative, he maintained that the “principal problem” he faces could be summed up in one succinct sentence: “I have no right to think the way I do because I’m black.” When Higginbotham was asked about this comment later in a television interview, he shot back: “He’s got a right to think whatever he wants to, but he does not have a right to be free of critique.”

Early in his tenure as a justice, Thomas arranged for a modernization of the court gym. He’s bigger than you’d expect for someone who is five foot eight and a half. He has a running back’s legs and a lineman’s chest, a body that always seems stuffed into his suits. He likes lifting weights. The court’s gym was freighted with outdated equipment, but Thomas turned the renovation into something defiantly delicious. In public and in private, he loved telling people that he planned to work out vigorously so that he could live a long life, stay on the court for forty or fifty years, and outlast all his critics. The story would sometimes be accompanied by that booming guttural laugh of his, but his intention was clear. He was sending a message to his tormentors: No matter how many shots you take at me, I’ll still be here.

It’s been sixteen years now and, indeed, some of his critics have passed on. A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. died on December 12, 1998, from a stroke. He was seventy.

Thomas never responded to his open letter.

From the Hardcover edition.

COURTING VENOM

Being Clarence Thomas

Dallas attorney Eric Moye received his copy in the mail from a fellow Harvard Law School alum. He started reading it but stopped to make a copy of the copy for a friend. He continued reading, absorbed, enchanted, depressed, exhilarated. Couldn’t put it down—except to make more copies.

It wasn’t a John Grisham thriller, but it might as well have been. “An Open Letter to Justice Clarence Thomas from a Federal Judicial Colleague” created an enormous buzz when the University of Pennsylvania Law Review published it in January 1992. Written by A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., chief judge emeritus of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, it was part history lesson and part admonition. Crafted with scholarly precision, it contained eighty–five footnotes and numerous citations of important court cases. But the essence of it read like a stern grandfather lecturing his bullheaded grandson: Don’t forget the roots of your success, boy, and the responsibilities you have to those who paved your way.

"You…must try to remember that the fundamental problems of the disadvantaged, women, minorities, and the powerless have not all been solved simply because you have ‘moved on up’ from Pin Point, Georgia, to the Supreme Court,” Higginbotham wrote in the conclusion of his twenty–four–page set of instructions to Thomas. Reciting a roster of notable names from the past, Higginbotham urged Thomas to see his life as connected to “the visions and struggles of Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Charles Hamilton Houston, A. Philip Randolph, Mary McLeod Bethune, W. E. B. Du Bois, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, Martin Luther King, Judge William Henry Hastie, Justices Thurgood Marshall, Earl Warren, and William Brennan, as well as the thousands of others who dedicated much of their lives to create the America that made your opportunities possible.”

The “open letter” read at times like a personal letter and was dated November 29, 1991, which was shortly after Thomas took his seat on the high court. Higginbotham felt ambivalent about making his letter public but did so, he said, to help this generation and future ones better evaluate Thomas. Because it was so well sourced and because it was penned by a black twenty–seven–year veteran of the federal bench, the letter as law review article carried an authority that most Thomas critiques did not.

As such, it received considerable attention. The University of Pennsylvania received more than seventeen thousand requests for reprints, and law offices around the country busily churned out photocopies.

“Sometimes chain letters circulate all over the place,” recalled Moye, “and this was kind of like one of those.” Nowhere was the interest greater than in black legal circles, where a robust debate was unfolding about what kind of justice Thomas would become. Moye, a former state district judge with a weakness for Cuban cigars and the finest steaks, acted as if he’d reached nirvana. After he made his first copy of the Higginbotham treatise and got his secretary to make five more copies, he bought the bound version to put on his office shelf. So many photocopies were in circulation that another one even came back to Moye—just like a chain letter.

“It was spreading like fire across the dry prairie,” Moye recalled. “Folks were calling one another speculating on whether Thomas would ever respond to Judge Higginbotham's open letter.”

The showdown marked the beginning of a transition in the way African Americans came to view Thomas, a shift that helped harden his image nationally. Gradually but inexorably, wariness supplanted wait–and–see as the predominant state of mind among blacks. Wariness became distrust, which blossomed into contempt.

“I'll put it like this,” said basketball legend Kareem Abdul Jabbar. “If he let people know that he was going to be at some public destination, let’s say in Harlem, at a certain hour on a certain day, let’s see how many supporters would show up and how many detractors would show up.” The National Basketball Association’s all–time leading scorer was another who had discovered Higginbotham’s law article and wondered: How can someone who benefited so richly from affirmative action not support the same remedy for those in similar circumstances?

Though his confirmation hearings left Thomas wounded and enraged, the good news should have been that initially, at least, more than twice as many African Americans, according to polls, believed him as believed Anita Hill. But Thomas couldn’t find the resolve to embrace that reassuring fact. He was shell–shocked by his ordeal and retreated into his work, which was difficult enough, and he was already behind. The court’s term began in October 1991. Because of his drawn–out confirmation process and the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s wife, Nan, Thomas wasn’t sworn in until the first day of November. He arrived with no staff, his law clerks weren’t up to speed, and he was hamstrung by his inexperience as a judge—he’d spent just nineteen months on the D.C. Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals. Plus he was bone tired.

Higginbotham was certainly no help. He became a more formidable nemesis, shedding the reproving grandpa role for the part of public castigator. In an attention–getting 1994 lecture at the Hastings College of Law in San Francisco, Higginbotham used his hour–long remarks to issue a stiff condemnation of Thomas’s jurisprudence. In one pointed comparison, he said he had studied every opinion written by Thomas and every one composed by his predecessor Marshall, and the difference between the two jurists was “the difference between zero and infinity.”

Then he dug the knife in even deeper.

“I have often pondered how it is that Justice Thomas, an African American, could be so insensitive to the plight of the powerless. Why is he no different, or probably worse, than many of the most conservative Supreme Court justices of this century? I can only think of one Supreme Court justice during this century who was worse than Justice Clarence Thomas: James McReynolds, a white supremacist who referred to blacks as ‘niggers.’ ”

Those in the packed auditorium couldn’t help but notice how emotional Higginbotham had become, his voice trembling, tears flowing. Removing his glasses, he wiped his eyes with a handkerchief. During Democratic presidencies, Higginbotham’s name often surfaced on short lists of potential Supreme Court nominees. But it never rose to the top. (In 1995, he would be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the closest thing a president can muster to a consolation prize.) The hard part was that Higginbotham was sixty–five and now retired, and not only had he been passed over for a position he had long coveted, he saw it snatched by a junior he felt had not earned it. Detractors attributed Higginbotham’s behavior to some combination of bitterness, jealousy, and a broken heart. But whatever his reasons, the blasts were effective. And the judgment that Thomas was the kind of black man no black person should admire mushroomed.

The catalog of Thomas–targeted insults is fat and brutal, and today the estrangement between the justice and broad swaths of his own people seems almost irreconcilable. Emerge, a since–departed African American–oriented news magazine owned by the country’s first black billionaire, Bob Johnson, twice parodied Thomas on its cover—once wearing an Aunt Jemima–style headscarf and another time as a lawn jockey. The editions were among the magazine’s best sellers. Ebony magazine, which annually publishes a list of the nation’s hundred most influential African Americans, routinely leaves Thomas off its tally. A former Kansas City mayor can make it, but not the nation’s only black Supreme Court justice?

Invitations for Thomas to speak are now carefully vetted. He has discovered that saying yes to an offer also could mean signing up for public humiliation: name–calling, pickets, boycotts. The mere announcement of a Thomas visit is apt to trigger a controversy. In the most famous such episode, the superintendent of the Prince George’s County, Maryland, school system disinvited Thomas from speaking at a middle school in 1996 after several black school board members complained and threatened protests. The school board overruled its schools' chief, and the show went on—demonstrations and all. (Later, a law clerk gave Thomas a placard that he proudly displayed in his chambers as a kind of combat medal. It read: “Banned in P.G. County.”)

Thomas has become more intimate with his opposition than he ever thought would be possible in the relatively isolated life of a Supreme Court justice. No venue is sacred. The Reverend Al Sharpton took his beef straight to Thomas’s home. He led four hundred demonstrators, who stepped off chartered buses, to a public road outside the justice's secluded suburban Virginia subdivision. There they denounced Thomas as a traitor. Nearly a decade later, Sharpton would campaign for president and continue his bashing of Thomas in a nationally televised debate, claiming, “He is my color, but he’s not my kind.” Even in academia, where philosophical debate is encouraged, five black University of North Carolina law professors boycotted a visit by Thomas in the spring of 2002.

Racial disillusionment is the common theme in all these demonstrations—not ideology, not politics, but the seething sense that one of the potential bright lights of the race has rejected his chance to shine. Otherwise, the black North Carolina professors would have howled about the appearances of Justice Antonin Scalia and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in preceding years. But they didn’t. As the professors wrote, explaining their position, in a nation “in which African Americans are disproportionately poor, undereducated, imprisoned and politically compromised, identity—racial identity—very clearly matters. Were that not the case, Justice Thomas, for all his claims to the contrary, could not have declared himself the victim of a ‘high–tech lynching’ during the heated opposition to his appointment to the Supreme Court.”

A special strain of animus seems reserved for Thomas. When the American Civil Liberties Union of Hawaii proposed inviting Thomas to a debate on affirmative action in 2003, black board member Eric Ferrer was furious. That would be tantamount to “inviting Hitler to come speak on the rights of Jews,” he fumed. Thomas didn’t accept the invitation, but Ferrer ended up resigning from the board over the mere fact that an invitation had been extended. “The appropriate word is venom,” said conservative media critic Brent Bozell, assessing what has happened to Thomas. “I would challenge you to find anyone on the left who has been the target of such a vitriolic character assassination campaign as has Clarence Thomas. I even challenge you to find anyone on the right who has. This man is in his own league.”

A league of his own, but one he has helped create, as far as Eric Moye is concerned. Moye, active in Democratic politics, was up for a federal appeals court judgeship during the Clinton administration. He still remembers some of Thomas’s harsh critiques of civil rights groups during his years as Ronald Reagan’s chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Thomas once told an interviewer that there was not a single area in which the NAACP was doing good work—“I can’t think of any”—and another time complained that all civil rights leaders do is “bitch, bitch, bitch, moan and moan, whine and whine.” Moye wonders if Thomas ever stops to think when he dons his robe: Where would I be if these civil rights figures had not carried the fight to statehouses and courthouses, had not taken the beatings, gone to jail, refused to wilt under exhausting oppression, and even been willing to die for equality? (Actually, Thomas has answered that question. He doesn’t credit civil rights leaders for his opportunities. “My grandfather—that’s the guy that got me out," he once told an interviewer. “It wasn’t all these people who are claiming all this leadership stuff.”)

As Moye sees it, Thomas has tilted so far away from his heritage that there is no longer any real debate about him. “I think there is a profound sense of despair,” Moye says. “In order to have disappointment you have to have high expectations. I think there were those who hoped he was going to blossom and develop. But I don’t think you know many African Americans, other than those who know him personally, who think he turned out all right.”

Comedians now use him as material. Rappers turn him into lyrics. This, from the song “Build and Destroy,” by KRS–One:

The white man ain’t the devil I promise

You want to see the devil take a look at Clarence Thomas.

Essayists have taken the Thomas–dissecting cottage industry to new heights. Michael Thelwell, an Afro–American studies scholar, writes: “Perhaps black people ought to give serious thought to retiring Clarence from general use as a name in our communities.”

This is what Moye was talking about—Thomas has become an infamous cultural symbol. The Notorious C.T.

In September 1997, Moye happened to be seated next to Judge Higginbotham at a Harvard Law School dinner at Legal Sea Foods in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At one point, still curious after all these years, Moye leaned over and asked if Higginbotham had ever received a private reply to his letter. No, the judge said, he hadn’t. It was the last time Moye would see Higginbotham.

Thomas was terribly bothered by Higginbotham’s criticism, he confided to friends, for it seemed to defy customary judicial decorum and was so unsparing. In 1998, Higginbotham opposed having Thomas speak to the National Bar Association convention in Memphis, saying it was like inviting George Wallace to dinner after he stood in the schoolhouse door and promised to maintain segregation forever. After the usual controversy over his appearance and much hand–wringing, Thomas did speak to the group. In remarks that veered from self–pitying to combative, he maintained that the “principal problem” he faces could be summed up in one succinct sentence: “I have no right to think the way I do because I’m black.” When Higginbotham was asked about this comment later in a television interview, he shot back: “He’s got a right to think whatever he wants to, but he does not have a right to be free of critique.”

Early in his tenure as a justice, Thomas arranged for a modernization of the court gym. He’s bigger than you’d expect for someone who is five foot eight and a half. He has a running back’s legs and a lineman’s chest, a body that always seems stuffed into his suits. He likes lifting weights. The court’s gym was freighted with outdated equipment, but Thomas turned the renovation into something defiantly delicious. In public and in private, he loved telling people that he planned to work out vigorously so that he could live a long life, stay on the court for forty or fifty years, and outlast all his critics. The story would sometimes be accompanied by that booming guttural laugh of his, but his intention was clear. He was sending a message to his tormentors: No matter how many shots you take at me, I’ll still be here.

It’s been sixteen years now and, indeed, some of his critics have passed on. A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. died on December 12, 1998, from a stroke. He was seventy.

Thomas never responded to his open letter.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The authors track the personal odyssey of Clarence Thomas from his poor childhood in Georgia to his law school years at Yale and his rise within the Republican political establishment. They offer a portrait of a man who straddles two different worlds and is comfortable in neither.

Premii

- Black Caucus of the American Library Association Literary_award Honor Book, 2008