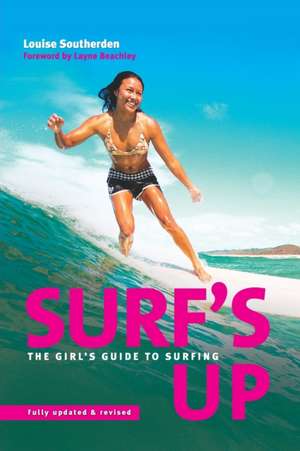

Surf's Up

Autor Louise Southerdenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 sep 2019

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 109.63 lei 22-36 zile | |

| BALLANTINE BOOKS – 28 feb 2005 | 109.63 lei 22-36 zile | |

| Louise Southerden – 18 sep 2019 | 348.31 lei 38-44 zile |

Preț: 348.31 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 522

Preț estimativ în valută:

66.65€ • 69.76$ • 55.47£

66.65€ • 69.76$ • 55.47£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 26 martie-01 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780992402518

ISBN-10: 0992402514

Pagini: 274

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: Louise Southerden

ISBN-10: 0992402514

Pagini: 274

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: Louise Southerden

Extras

In the beginning . . .

With more and more women now taking their place in surf spots around the world, gaining confidence and finding that they belong out there as much as anyone, it’s tempting to think that women’s surfing is a new phenomenon. But females have been surfing for longer than you think.

In fact you could say that women have always had a kinship with the waves. The ocean is, after all, female—ask any poet. Maybe it’s because the sea can be so beautiful and full of life, stormy and quiet, gentle and powerful, all at once. There are myths about women surfing long ago in Tahiti, Aotearoa (New Zealand), and Rapa Nui (Easter Island). And don’t tell the guys, but according to one Hawaiian legend, women even learned to surf before men: when Kamohoali’I, the shark god, taught Pele, the goddess of volcanoes, how to surf.

Why the history lesson?

Why is any of this important? It goes without saying that you need to look where you’re going when you’re learning something new, but a glance backward through time, learning about the people who cleared the path and understanding how surfing evolved, can be both informative and inspiring. If women could learn to surf—and surf well—when surfboards weighed a ton, there were no surf schools, and boardshorts and leashes were yet to be invented, then hey, maybe it’s not so hard after all.

It’s also important to know our roots. The history of surfing has been well documented over the years, but often with a subtle bias. You’d be hard pressed to find a surfer today who’s never heard of Midget Farrelly, the first men’s world surfing champion. But who’s heard of Phyllis O’Donnell, the first women’s world champion, who stood beside Midget on the winner’s dais at the first World Championships, held at Sydney’s Manly Beach in 1964?

It’s not a conspiracy—just a side effect of the way events were recorded in those days and the amount of media coverage devoted to women’s events—but it’s not the full story either. Of course, a comprehensive history of surfing including the advances made by men and women would fill an entire book by itself. So the role of this chapter is to shine a light on a few of the women who have been part of the evolution of surfing. (By the way, if you’re eager to get to the nitty-gritty of learning to surf, feel free to go straight to Chapter 2. That’s the beauty of history: You can always come back to it later).

Think of it as looking back over your shoulder at all the dedicated surfer girls who have gone before you. Of course, women’s surfing isn’t separate from or superior to (or inferior to) men’s surfing. But women are part of the bigger picture and, if the truth be known, always have been. In fact we’re making history right now just by getting out there and making women’s surfing visible once again.

Hawaii, a.d. 4

Imagine yourself in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, on a small group of islands that have always loomed large in surfing’s history: Hawaii, the birthplace of modern surfing. Now turn back the clock two thousand years to a.d. 4 when Polynesians started coming ashore. It’s hard to imagine a race of people more in sync with the ocean than the first Polynesians, particularly those who braved the long voyage to Hawaii. Of course, they already knew how to surf, but they did it lying down on short flat belly boards called paipo. It was the Hawaiians who took surfing up a notch, literally—by standing on longer surfboards.

Surfing was huge in Hawaii before European settlement, and it wasn’t just a guy thing. Whole villages of men and women would surf together, sing songs to bring waves, and observe rituals and beliefs associated with the simple act of riding a wave. Surfing was even regarded as a kind of ocean-blessed foreplay; if a man and a woman rode a wave together, Hawaiian law permitted them to, er, get friendly on the sand when they got back to the beach.

Hawaiian social classes even extended past the shore break: There were surf breaks for royalty and surf breaks for commoners, and while Hawaiian princesses rode massive boards called olo that were up to 18 feet long (almost twice as long as the longest surfboards today), commoners rode shorter 12-foot boards called alaia. (The first surfboard to grace Australia’s shores was actually an alaia. Manly Beach local C. D. Paterson lugged it back to Sydney from a trip to Hawaii in 1912. He tried to ride it but was so unsuccessful he gave it to his mom to use as an ironing board!)

1900–15: The first “beach girls”

This idyllic existence continued until 1778, when Captain James Cook made the first recorded European visit to the islands, bringing previously unheard-of diseases that decimated Hawaii’s population from around half a million to barely forty thousand. In a few short years, Hawaii’s surfers were almost wiped out. The ones who survived soon had to contend with the puritanical missionaries who arrived in 1820, dismissed surfing as un-Christian, and virtually outlawed wave-riding for everyone but the royal family.

Surfing languished in this forbidden zone for almost a hundred years until the early 1900s, when missionaries began to lose their grip on the islands. Unfortunately, new ways of life had been adopted in the meantime, which was bad news for Hawaiian women; instead of going surfing, they were now expected to spend all their time cooking, cleaning, and looking after the kids. For the first time in history, surfing had become “men only.”

Eventually, however, the Hawaiians’ longing for their favorite pastime won out. Hawaii became a holiday destination for visiting mainlanders during the early 1900s, and the local “beach boys” who hung out at Waikiki, the hub of the new tourism, started taking them out into the waves, first on outrigger canoes and then surfboards. This was a breath of fresh air for Hawaiian culture and resulted in many of Hawaii’s women taking to the waves again. The newly formed Hui Nalu (Surf Club) even had two female members, Mildred (Ladybird) Turner, and Waikiki “beach girl” Josephine (Jo) Pratt, who became widely regarded as Hawaii’s most accomplished female surfboard rider between 1909 and 1911.

1907: Surfing comes to the United States

Surfing officially graced the shores of mainland America in July 1907 when Hawaiian beach boy George Freeth started giving paid surfing demonstrations at Redondo Beach and Venice Beach, California. Although he wasn’t the first person to surf in California—a handful of Hawaiian princes who were attending military school in California had demonstrated “surf sliding” in Santa Cruz as early as 1885—it was Freeth who really ignited surfing in America’s consciousness.

Another Waikiki beach boy to attain surf-star status in the early 1900s was the gorgeously handsome champion swimmer Duke Kahanamoku. On his way to winning a gold medal for the 100-meter freestyle at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Duke stopped in Southern California to give a few surfing demonstrations at Corona del Mar and Santa Monica and caused quite a stir among the SoCal locals. On his way back from Sweden, Duke also took the time to introduce surfing to the East Coast, surfing for the crowds in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Duke also popularized tandem surfing—when two surfers (usually a guy and a girl) ride the same board—which he demonstrated all over the world, including Sydney, Australia, in the summer of 1914–15.

1915: Surfing arrives in Australia

It’s hard to imagine a more prehistoric era in the history of surfing than Australia in the early 1900s. Picture this: You’re forbidden to swim during daylight hours (the ban on public bathing between 6 a.m. and 8 p.m. was lifted at Manly Beach in Sydney in 1902, and other beaches followed suit soon after); swimming zones are segregated for guys and girls; and when you do get in the water you have to wear a long-sleeved woolen swimsuit that’s ten times heavier when it’s wet than when it’s dry.

Into this setting came the Duke, a bronzed Hawaiian swimming and surfing god, in 1915. Although initially invited by the New South Wales Swimming Association to give a public swimming demonstration, it was Duke’s surfing skills that had the biggest impact on the Australian public. Australians had been surfing lying down on 4-to-5 foot wooden surfboards and bodysurfing with wooden handboards—some had even heard about stand-up surfing in Hawaii and seen a couple of local surfers standing up—but stand-up surfing was still more of a rumor than a reality for most Aussie beachgoers at the time.

It’s something of a coup for women’s surfing that one of the first Australians to stand up on a surfboard was a fifteen-year-old girl. Isabel Letham was just about to turn sweet sixteen when Duke made an appearance at Sydney’s Freshwater Beach to give a demonstration of “Hawaiian-style surf-shooting.” It was a rainy Sunday in January 1915, and several hundred Sydney-siders had turned out to watch Duke’s unusual antics on the wave: first he paddled out lying down (instead of kneeling as most Aussies had done before then), and when he caught a wave he stood up and angled across it instead of heading straight toward the beach.

When Duke asked for a girl from the crowd to go tandem surfing with him, the organizers of the event knew just who to pick. Letham was renowned for her tomboyish behavior; at a time when most girls were embroidering hankies, she was spending every spare minute down at the beach swimming and bodysurfing. She was also a natural choice because Duke hadn’t brought a surfboard with him to Australia and her dad had helped him to make a traditional Hawaiian surfboard from a log of sugar pine.

On the first few waves they paddled for, Letham was so scared, she made Duke stop because she said it felt like they were going over a cliff. Gentleman that he was, Duke did stop—the first few times—but he finally ignored her cries and took off on a wave, hauling her up by the scruff of her neck to stand beside him. They rode four waves that day, and by the time they returned to terra firma Letham was hooked. She became a dedicated surfer, teaching others to swim and surf in all conditions. In 1918 she traveled to America to find work as a Hollywood stuntwoman and was appointed Director of Swimming at the San Francisco Women’s City Club, where she taught remedial swimming to disabled women. She was an inspiration to all women surfers right up until she died in 1995 at the age of ninety-five.

Soon everyone in Australia was surfing standing up. In fact surfing became so big that popular beaches such as Coolangatta on the Gold Coast introduced restricted surfing zones, punishable by board confiscation. Manly Council in Sydney even banned surfboards from the beach altogether until several board-aided rescues in 1923 forced it to reverse its decision.

1920s: The first surfer girls

Until the 1920s, surfing’s popularity among women, outside Hawaii, was limited by one important factor: surfboards were huge. Think 12 feet long, made from solid timber, and weighing almost 100 pounds. Not only that but they didn’t have any fins, which meant they were impossible to turn; if you did want to turn, you had to put one foot in the water (ever tried to keep your balance on a moving surfboard with one foot dragging in the sea?). At least it made surfing more sociable. Most surfers rode their boards straight to the beach, which meant that more than one surfer could ride each wave.

One way to get out there when surfboards were so cumbersome was to tag along with a guy. The first women surfers in Southern California often went tandem surfing with their boyfriends. They’d go to the beach together, ride the board together; then, if the girl was interested enough, she might take it up and get her own board. There were more independent-minded women, though, like the legendary Mary Ann Hawkins. In the tradition of Hawaiian surfers before her, Hawkins was an all-around waterwoman: surfer, bodysurfer, and long-distance swimmer. She was one of the first surfing females to earn the respect of the fledgling Californian surfing fraternity for her wave-riding throughout the 1930s and ’40s and one of the first people to surf Palos Verdes, where she used to lug her 80-pound redwood surfboard up and down the cliffs on her way to and from the beach. For all this and more, Hawkins has been called the greatest woman surfer in the first half of the twentieth century.

Surfing got another boost during World War II when thousands of women (and men) were stationed at U.S. military bases in Hawaii. Some of them took up surfing; others just wrote home about the beautiful beaches and waves. This was the beginning of the annual winter pilgrimage of surfers to Hawaii for the big swells that hit the islands between December and March, a tradition that continues today; some of the most anticipated contests of the pro tour are those held in December at Sunset and Pipeline on the North Shore of Oahu, and on the island of Maui.

1950s: “Girl Boards”

In the late 1940s, using new materials developed during World War II, Californian shapers started making surfboards from a lightweight wood called balsa, which they’d salvaged from ex-navy life rafts. Balsa surfboards were a major breakthrough. Lighter and more buoyant, they made the waves accessible to more girls, not just muscle-bound guys.

In the 1950s, Californian shaper Joe Quigg made three balsa “Girl Boards” for three Malibu surfer girls: Vicki Flaxman, Aggie Bane, and Robin Grigg. Each girl painted her name and a design on her Girl Board, but what was really different about these surfboards was that they were curved from nose to tail, in contrast to the flat-as-a-plank boards of the time. As a result they were much easier to turn—they also allowed you to walk to the nose and do tricks—and when the guys saw how easily the girls were riding them, they all wanted one too.

Quigg went on to make surfboards for other surfer girls, one of whom was Marge Calhoun, who came to surfing through her work as a water stuntwoman in Hollywood. In 1958, Calhoun and fellow Californian Eve Fletcher (who had only learned to surf the year before, when she was thirty) flew to Hawaii to compete in the Makaha International contest—they paid legendary surfer Fred Van Dyke $100 to live in his panel truck for a month—and Calhoun subsequently won, on a 10-foot balsa board. There was no women’s professional circuit back then, but this was the beginning of women competing in surfing.

1957–59: Gidget goes surfing

In 1957, surfing hit the mainstream thanks to a fifteen-year-old named Kathy Kohner, aka Gidget. After living in Europe for a year, Kohner and her family moved back to Malibu Beach, California.

With more and more women now taking their place in surf spots around the world, gaining confidence and finding that they belong out there as much as anyone, it’s tempting to think that women’s surfing is a new phenomenon. But females have been surfing for longer than you think.

In fact you could say that women have always had a kinship with the waves. The ocean is, after all, female—ask any poet. Maybe it’s because the sea can be so beautiful and full of life, stormy and quiet, gentle and powerful, all at once. There are myths about women surfing long ago in Tahiti, Aotearoa (New Zealand), and Rapa Nui (Easter Island). And don’t tell the guys, but according to one Hawaiian legend, women even learned to surf before men: when Kamohoali’I, the shark god, taught Pele, the goddess of volcanoes, how to surf.

Why the history lesson?

Why is any of this important? It goes without saying that you need to look where you’re going when you’re learning something new, but a glance backward through time, learning about the people who cleared the path and understanding how surfing evolved, can be both informative and inspiring. If women could learn to surf—and surf well—when surfboards weighed a ton, there were no surf schools, and boardshorts and leashes were yet to be invented, then hey, maybe it’s not so hard after all.

It’s also important to know our roots. The history of surfing has been well documented over the years, but often with a subtle bias. You’d be hard pressed to find a surfer today who’s never heard of Midget Farrelly, the first men’s world surfing champion. But who’s heard of Phyllis O’Donnell, the first women’s world champion, who stood beside Midget on the winner’s dais at the first World Championships, held at Sydney’s Manly Beach in 1964?

It’s not a conspiracy—just a side effect of the way events were recorded in those days and the amount of media coverage devoted to women’s events—but it’s not the full story either. Of course, a comprehensive history of surfing including the advances made by men and women would fill an entire book by itself. So the role of this chapter is to shine a light on a few of the women who have been part of the evolution of surfing. (By the way, if you’re eager to get to the nitty-gritty of learning to surf, feel free to go straight to Chapter 2. That’s the beauty of history: You can always come back to it later).

Think of it as looking back over your shoulder at all the dedicated surfer girls who have gone before you. Of course, women’s surfing isn’t separate from or superior to (or inferior to) men’s surfing. But women are part of the bigger picture and, if the truth be known, always have been. In fact we’re making history right now just by getting out there and making women’s surfing visible once again.

Hawaii, a.d. 4

Imagine yourself in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, on a small group of islands that have always loomed large in surfing’s history: Hawaii, the birthplace of modern surfing. Now turn back the clock two thousand years to a.d. 4 when Polynesians started coming ashore. It’s hard to imagine a race of people more in sync with the ocean than the first Polynesians, particularly those who braved the long voyage to Hawaii. Of course, they already knew how to surf, but they did it lying down on short flat belly boards called paipo. It was the Hawaiians who took surfing up a notch, literally—by standing on longer surfboards.

Surfing was huge in Hawaii before European settlement, and it wasn’t just a guy thing. Whole villages of men and women would surf together, sing songs to bring waves, and observe rituals and beliefs associated with the simple act of riding a wave. Surfing was even regarded as a kind of ocean-blessed foreplay; if a man and a woman rode a wave together, Hawaiian law permitted them to, er, get friendly on the sand when they got back to the beach.

Hawaiian social classes even extended past the shore break: There were surf breaks for royalty and surf breaks for commoners, and while Hawaiian princesses rode massive boards called olo that were up to 18 feet long (almost twice as long as the longest surfboards today), commoners rode shorter 12-foot boards called alaia. (The first surfboard to grace Australia’s shores was actually an alaia. Manly Beach local C. D. Paterson lugged it back to Sydney from a trip to Hawaii in 1912. He tried to ride it but was so unsuccessful he gave it to his mom to use as an ironing board!)

1900–15: The first “beach girls”

This idyllic existence continued until 1778, when Captain James Cook made the first recorded European visit to the islands, bringing previously unheard-of diseases that decimated Hawaii’s population from around half a million to barely forty thousand. In a few short years, Hawaii’s surfers were almost wiped out. The ones who survived soon had to contend with the puritanical missionaries who arrived in 1820, dismissed surfing as un-Christian, and virtually outlawed wave-riding for everyone but the royal family.

Surfing languished in this forbidden zone for almost a hundred years until the early 1900s, when missionaries began to lose their grip on the islands. Unfortunately, new ways of life had been adopted in the meantime, which was bad news for Hawaiian women; instead of going surfing, they were now expected to spend all their time cooking, cleaning, and looking after the kids. For the first time in history, surfing had become “men only.”

Eventually, however, the Hawaiians’ longing for their favorite pastime won out. Hawaii became a holiday destination for visiting mainlanders during the early 1900s, and the local “beach boys” who hung out at Waikiki, the hub of the new tourism, started taking them out into the waves, first on outrigger canoes and then surfboards. This was a breath of fresh air for Hawaiian culture and resulted in many of Hawaii’s women taking to the waves again. The newly formed Hui Nalu (Surf Club) even had two female members, Mildred (Ladybird) Turner, and Waikiki “beach girl” Josephine (Jo) Pratt, who became widely regarded as Hawaii’s most accomplished female surfboard rider between 1909 and 1911.

1907: Surfing comes to the United States

Surfing officially graced the shores of mainland America in July 1907 when Hawaiian beach boy George Freeth started giving paid surfing demonstrations at Redondo Beach and Venice Beach, California. Although he wasn’t the first person to surf in California—a handful of Hawaiian princes who were attending military school in California had demonstrated “surf sliding” in Santa Cruz as early as 1885—it was Freeth who really ignited surfing in America’s consciousness.

Another Waikiki beach boy to attain surf-star status in the early 1900s was the gorgeously handsome champion swimmer Duke Kahanamoku. On his way to winning a gold medal for the 100-meter freestyle at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Duke stopped in Southern California to give a few surfing demonstrations at Corona del Mar and Santa Monica and caused quite a stir among the SoCal locals. On his way back from Sweden, Duke also took the time to introduce surfing to the East Coast, surfing for the crowds in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Duke also popularized tandem surfing—when two surfers (usually a guy and a girl) ride the same board—which he demonstrated all over the world, including Sydney, Australia, in the summer of 1914–15.

1915: Surfing arrives in Australia

It’s hard to imagine a more prehistoric era in the history of surfing than Australia in the early 1900s. Picture this: You’re forbidden to swim during daylight hours (the ban on public bathing between 6 a.m. and 8 p.m. was lifted at Manly Beach in Sydney in 1902, and other beaches followed suit soon after); swimming zones are segregated for guys and girls; and when you do get in the water you have to wear a long-sleeved woolen swimsuit that’s ten times heavier when it’s wet than when it’s dry.

Into this setting came the Duke, a bronzed Hawaiian swimming and surfing god, in 1915. Although initially invited by the New South Wales Swimming Association to give a public swimming demonstration, it was Duke’s surfing skills that had the biggest impact on the Australian public. Australians had been surfing lying down on 4-to-5 foot wooden surfboards and bodysurfing with wooden handboards—some had even heard about stand-up surfing in Hawaii and seen a couple of local surfers standing up—but stand-up surfing was still more of a rumor than a reality for most Aussie beachgoers at the time.

It’s something of a coup for women’s surfing that one of the first Australians to stand up on a surfboard was a fifteen-year-old girl. Isabel Letham was just about to turn sweet sixteen when Duke made an appearance at Sydney’s Freshwater Beach to give a demonstration of “Hawaiian-style surf-shooting.” It was a rainy Sunday in January 1915, and several hundred Sydney-siders had turned out to watch Duke’s unusual antics on the wave: first he paddled out lying down (instead of kneeling as most Aussies had done before then), and when he caught a wave he stood up and angled across it instead of heading straight toward the beach.

When Duke asked for a girl from the crowd to go tandem surfing with him, the organizers of the event knew just who to pick. Letham was renowned for her tomboyish behavior; at a time when most girls were embroidering hankies, she was spending every spare minute down at the beach swimming and bodysurfing. She was also a natural choice because Duke hadn’t brought a surfboard with him to Australia and her dad had helped him to make a traditional Hawaiian surfboard from a log of sugar pine.

On the first few waves they paddled for, Letham was so scared, she made Duke stop because she said it felt like they were going over a cliff. Gentleman that he was, Duke did stop—the first few times—but he finally ignored her cries and took off on a wave, hauling her up by the scruff of her neck to stand beside him. They rode four waves that day, and by the time they returned to terra firma Letham was hooked. She became a dedicated surfer, teaching others to swim and surf in all conditions. In 1918 she traveled to America to find work as a Hollywood stuntwoman and was appointed Director of Swimming at the San Francisco Women’s City Club, where she taught remedial swimming to disabled women. She was an inspiration to all women surfers right up until she died in 1995 at the age of ninety-five.

Soon everyone in Australia was surfing standing up. In fact surfing became so big that popular beaches such as Coolangatta on the Gold Coast introduced restricted surfing zones, punishable by board confiscation. Manly Council in Sydney even banned surfboards from the beach altogether until several board-aided rescues in 1923 forced it to reverse its decision.

1920s: The first surfer girls

Until the 1920s, surfing’s popularity among women, outside Hawaii, was limited by one important factor: surfboards were huge. Think 12 feet long, made from solid timber, and weighing almost 100 pounds. Not only that but they didn’t have any fins, which meant they were impossible to turn; if you did want to turn, you had to put one foot in the water (ever tried to keep your balance on a moving surfboard with one foot dragging in the sea?). At least it made surfing more sociable. Most surfers rode their boards straight to the beach, which meant that more than one surfer could ride each wave.

One way to get out there when surfboards were so cumbersome was to tag along with a guy. The first women surfers in Southern California often went tandem surfing with their boyfriends. They’d go to the beach together, ride the board together; then, if the girl was interested enough, she might take it up and get her own board. There were more independent-minded women, though, like the legendary Mary Ann Hawkins. In the tradition of Hawaiian surfers before her, Hawkins was an all-around waterwoman: surfer, bodysurfer, and long-distance swimmer. She was one of the first surfing females to earn the respect of the fledgling Californian surfing fraternity for her wave-riding throughout the 1930s and ’40s and one of the first people to surf Palos Verdes, where she used to lug her 80-pound redwood surfboard up and down the cliffs on her way to and from the beach. For all this and more, Hawkins has been called the greatest woman surfer in the first half of the twentieth century.

Surfing got another boost during World War II when thousands of women (and men) were stationed at U.S. military bases in Hawaii. Some of them took up surfing; others just wrote home about the beautiful beaches and waves. This was the beginning of the annual winter pilgrimage of surfers to Hawaii for the big swells that hit the islands between December and March, a tradition that continues today; some of the most anticipated contests of the pro tour are those held in December at Sunset and Pipeline on the North Shore of Oahu, and on the island of Maui.

1950s: “Girl Boards”

In the late 1940s, using new materials developed during World War II, Californian shapers started making surfboards from a lightweight wood called balsa, which they’d salvaged from ex-navy life rafts. Balsa surfboards were a major breakthrough. Lighter and more buoyant, they made the waves accessible to more girls, not just muscle-bound guys.

In the 1950s, Californian shaper Joe Quigg made three balsa “Girl Boards” for three Malibu surfer girls: Vicki Flaxman, Aggie Bane, and Robin Grigg. Each girl painted her name and a design on her Girl Board, but what was really different about these surfboards was that they were curved from nose to tail, in contrast to the flat-as-a-plank boards of the time. As a result they were much easier to turn—they also allowed you to walk to the nose and do tricks—and when the guys saw how easily the girls were riding them, they all wanted one too.

Quigg went on to make surfboards for other surfer girls, one of whom was Marge Calhoun, who came to surfing through her work as a water stuntwoman in Hollywood. In 1958, Calhoun and fellow Californian Eve Fletcher (who had only learned to surf the year before, when she was thirty) flew to Hawaii to compete in the Makaha International contest—they paid legendary surfer Fred Van Dyke $100 to live in his panel truck for a month—and Calhoun subsequently won, on a 10-foot balsa board. There was no women’s professional circuit back then, but this was the beginning of women competing in surfing.

1957–59: Gidget goes surfing

In 1957, surfing hit the mainstream thanks to a fifteen-year-old named Kathy Kohner, aka Gidget. After living in Europe for a year, Kohner and her family moved back to Malibu Beach, California.

Recenzii

"The objective in surfing, whether you’re learning or competing as a pro, is to have fun, and Louise Southerden’s book will show you how to do that."

–Serena Brooke, professional surfer

“One surfer can change the tone of the whole line up–if you go out there and be friendly and have fun, pretty soon everyone around you will be having fun too. Louise Southerden’s Surf’s Up: The Girl’s Guide to Surfing gives all women young and old the foundation and the tips to feel confident enough to have fun and go surf!”

–Kathy Phillips, director, Eastern Surfing Association

–Serena Brooke, professional surfer

“One surfer can change the tone of the whole line up–if you go out there and be friendly and have fun, pretty soon everyone around you will be having fun too. Louise Southerden’s Surf’s Up: The Girl’s Guide to Surfing gives all women young and old the foundation and the tips to feel confident enough to have fun and go surf!”

–Kathy Phillips, director, Eastern Surfing Association

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

A girlfriend's guide to surfing is penned by one of Australia's leading surfing journalists and a surfer girl herself. Photos throughout.

A girlfriend's guide to surfing is penned by one of Australia's leading surfing journalists and a surfer girl herself. Photos throughout.

Notă biografică

Louise Southerden is a surfer, writer, and former editor of SurfGirl magazine. She is the author of Surf's Up. Having lived the surfing lifestyle for more than 12 years and ridden waves all over Australia as well as overseas, she is now based on Sydney's northern beaches, where she divides her time between her laptop and the waves.