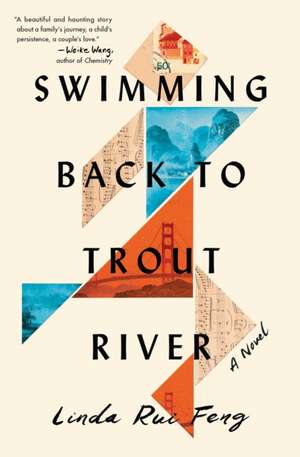

Swimming Back to Trout River

Autor Linda Rui Fengen Limba Engleză Paperback – 17 mai 2022

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 91.92 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Simon&Schuster – 17 mai 2022 | 91.92 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Simon&Schuster – 11 mai 2021 | 107.81 lei 3-5 săpt. | +10.39 lei 7-13 zile |

Preț: 91.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 138

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.59€ • 19.18$ • 14.83£

17.59€ • 19.18$ • 14.83£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-17 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982129415

ISBN-10: 1982129417

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 136 x 211 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

ISBN-10: 1982129417

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 136 x 211 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Notă biografică

Born in Shanghai, Linda Rui Feng has lived in San Francisco, New York, and Toronto. She is a graduate of Harvard and Columbia Universities and is currently a professor of Chinese cultural history at the University of Toronto. She has been twice awarded a MacDowell Fellowship for her fiction, and her prose and poetry have appeared in journals such as The Fiddlehead, The Kenyon Review, Santa Monica Review, and Washington Square Review. Swimming Back to Trout River is her first novel. Visit LindaRuiFeng.com to learn more.