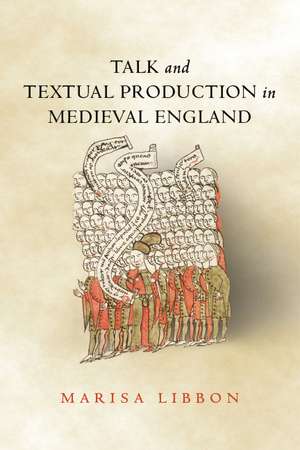

Talk and Textual Production in Medieval England: Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture

Autor Marisa Libbonen Limba Engleză Hardback – 8 apr 2021

People in medieval England talked, and yet we seldom talk or write about their talk. People conversed not within literary texts, but in the world in which those texts were composed and copied. The absence of such talk from our record of the medieval past is strange. Its absence from our formulation of medieval literary history is stranger still. In Talk and Textual Production in Medieval England, Marisa Libbon argues that talk among medieval England’s public, especially talk about history and identity, was essential to the production of texts and was a fundamental part of the transmission and reception of literature. Examining Richard I’s life as an exemplary subject of medieval England’s class-crossing talk about the past, Libbon advances a theory of how talk circulates history, identity, and cultural memory over time. By identifying sites of local talk about England's past, from law courts to palace chambers, and tracing rumors about Richard that circulated during his life and long after his death, Libbon offers a literary history of Richard that accounts for the spaces between and around extant manuscript copies of Middle English romances like Richard Coeur de Lion, insular and Continental chronicles, and chansons de geste with figures such as Charlemagne and Roland. These spaces, usually dismissed as silent, tell us about the processes of writing and reading and illuminate the intangible daily life in which textual production occurred. In revealing the pressures that talk about the past exerted on textual production, this bookrelocates the power of making culture and collective memory to a wider, collaborative authorship in medieval England.

Preț: 588.22 lei

Preț vechi: 763.93 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 882

Preț estimativ în valută:

112.56€ • 117.81$ • 93.68£

112.56€ • 117.81$ • 93.68£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814214701

ISBN-10: 0814214703

Pagini: 252

Ilustrații: 2 b&w

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture

ISBN-10: 0814214703

Pagini: 252

Ilustrații: 2 b&w

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture

Recenzii

“Incisive, clarifying, and often trenchant … Talk and Textual Production in Medieval England will be required reading for anyone working on Richard Coeur de Lion, and on the manuscript history of medieval romance more generally.” —Heather Blurton, Studies in the Age of Chaucer

“Marisa Libbon has provided evidence and argument about the seven manuscripts of the romance Richard Coeur de Lion that will fascinate anyone interested in book history … Plotted out cleverly and written with verve, Talk and Textual Production is a credit to the series in which it appears.” —Edwin Craun, The Medieval Review

“Strikingly original and thought-provoking … Talk should be an essential feature of manuscript and archival studies, book history, and historiography. Libbon shows us how important it is and how well it can work.” —Jamie K. Taylor, Manuscript Studies

“A brilliant book—bold and engaging, full of fresh insights.” —Eleanor Johnson, author of Practicing Literary Theory in the Middle Ages

“Talk and Textual Production in Medieval England convincingly integrates manuscript studies and book history with readings of the social urgencies that drive literary production. It is beautifully written, original in its evidential strategies, and richly, deeply, and productively researched.” —Christine Chism, author of Alliterative Revivals

Notă biografică

Marisa Libbon is Assistant Professor of Literature and Medieval Studies at Bard College.

Extras

People in medieval England talked. This may seem a fact too obvious for words, but we ourselves seldom talk or write about their talk. What they might have said not in the literary texts that preserve representations of the medieval world, but in the actual world that existed outside of those texts: the ongoing conversations among people about the matters of the day, conversations to which anyone could have access and over which no single institution had control. The absence of such talk from our record of the medieval English past is strange. Its absence from our formulation of medieval literary history, and thus the way in which we do not account for the presence of talk or the pressures it might have exerted, is stranger still. The idea that medieval textual production could have occurred without talk is utterly contradicted by a facet of our own lived experience, about which nothing is uniquely modern. Before and after texts are written, they are embedded in a surround of conversations essential to their making. Talking prompts writing and rewriting, and discussion and debate follow reading.

This book advances a theory of how talk circulates history, identity, and cultural memory over time. Circulating talk, then, becomes central and generative, a crucial context for the making and reading of medieval England’s literature. Moreover, talk was understood to be so in medieval England. In this book, I offer a literary history that accounts for the spaces between and around extant texts: spaces that scholars of medieval literature, especially, have tended to assume either silent or impossible to excavate, but which in fact can be made to speak, made to disclose information about the processes of writing and reading, and about the intangible daily life in which textual production occurred.

As the contents of these textless and seemingly empty spaces are recovered and made to mean, surviving texts are not necessarily prioritized as the sole or even the central bearers of evidence for literature’s inception, transmission, and reception. That mythical creature of medieval manuscript catalogues and medievalists’ thinking, the “now lost” copy of a text, is a response that we too often project upon the presumed silence of the past. We conjecture either generations that preceded the earliest extant manuscript copy of a text or a loss that we assume obscures our understanding of the surviving copies. Yet these conventional and familiar narratives we deploy to explain the seemingly abrupt presence of a “new” text on the medieval scene or the apparently nonsensical discrepancies among a text’s surviving manuscript copies preemptively foreclose our access to the past. To include talk in our project of cultural recovery is fundamentally disruptive, both to our methods, which call for precision and which we use to plot the spectrum of plausible ways things might have happened, and to our imaginations, with which we fashion the always in-progress picture of the past we as scholars produce.

To include talk in our rendering of the past is to make visible the contributions of the broader public to medieval England’s literature. People in medieval England, whatever their literacy or proximity to books, had access to talk. They could spread or suppress certain strands of it, and therefore were integral to text-making, both the kinds of texts that were made and what those texts were made to say. Talk is democratizing. The systematic exclusion of talk as essentially formative to literary texts has yielded a literary and cultural history that insists upon the silence of the past. In truth, that silence is predicated on our own perceived inability or habituated disinclination to listen.

This book advances a theory of how talk circulates history, identity, and cultural memory over time. Circulating talk, then, becomes central and generative, a crucial context for the making and reading of medieval England’s literature. Moreover, talk was understood to be so in medieval England. In this book, I offer a literary history that accounts for the spaces between and around extant texts: spaces that scholars of medieval literature, especially, have tended to assume either silent or impossible to excavate, but which in fact can be made to speak, made to disclose information about the processes of writing and reading, and about the intangible daily life in which textual production occurred.

As the contents of these textless and seemingly empty spaces are recovered and made to mean, surviving texts are not necessarily prioritized as the sole or even the central bearers of evidence for literature’s inception, transmission, and reception. That mythical creature of medieval manuscript catalogues and medievalists’ thinking, the “now lost” copy of a text, is a response that we too often project upon the presumed silence of the past. We conjecture either generations that preceded the earliest extant manuscript copy of a text or a loss that we assume obscures our understanding of the surviving copies. Yet these conventional and familiar narratives we deploy to explain the seemingly abrupt presence of a “new” text on the medieval scene or the apparently nonsensical discrepancies among a text’s surviving manuscript copies preemptively foreclose our access to the past. To include talk in our project of cultural recovery is fundamentally disruptive, both to our methods, which call for precision and which we use to plot the spectrum of plausible ways things might have happened, and to our imaginations, with which we fashion the always in-progress picture of the past we as scholars produce.

To include talk in our rendering of the past is to make visible the contributions of the broader public to medieval England’s literature. People in medieval England, whatever their literacy or proximity to books, had access to talk. They could spread or suppress certain strands of it, and therefore were integral to text-making, both the kinds of texts that were made and what those texts were made to say. Talk is democratizing. The systematic exclusion of talk as essentially formative to literary texts has yielded a literary and cultural history that insists upon the silence of the past. In truth, that silence is predicated on our own perceived inability or habituated disinclination to listen.

Cuprins

Acknowledgments Abbreviations Note on Translations and Transcriptions Introduction Tuning Our Ears 1 Local Talk and the Retrospective Text 2 Public Talk and Legal Fictions 3 Talking Pictures in Fourteenth-Century London 4 The Conversant Codex 5 English Rumor and the Modular Manuscript Epilogue Turning Up the Archive Bibliography Index

Descriere

Uses the life of Richard I to argue that medieval England's public talk was essential to the production of texts and was a fundamental part of the transmission and reception of literature.