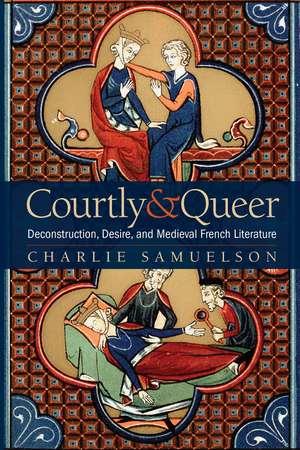

Courtly and Queer: Deconstruction, Desire, and Medieval French Literature: Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture

Autor Charlie Samuelsonen Limba Engleză Hardback – 24 mar 2022

In Courtly and Queer, Charlie Samuelson casts queerness in medieval French texts about courtly love in a new light by bringing together for the first time two exemplary genres: high medieval verse romance, associated with the towering figure of Chrétien de Troyes, and late medieval dits, primarily associated with Guillaume de Machaut. In close readings informed by deconstruction and queer theory, Samuelson argues that the genres’ juxtaposition opens up radical new perspectives on the deviant poetics and gender and sexual politics of both. Contrary to a critical tradition that locates the queer Middle Ages at the margins of these courtly genres, Courtly and Queer emphasizes an unflagging queerness that is inseparable from poetic indeterminacy and that inhabits the core of a literary tradition usually assumed to be conservative and patriarchal. Ultimately, Courtly and Queer contends that one facet of texts commonly referred to as their “courtliness”—namely, their literary sophistication—powerfully overlaps with modern conceptions of queerness.

Preț: 650.51 lei

Preț vechi: 844.81 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 976

Preț estimativ în valută:

124.51€ • 135.30$ • 104.66£

124.51€ • 135.30$ • 104.66£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 17-23 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814214985

ISBN-10: 0814214983

Pagini: 242

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture

ISBN-10: 0814214983

Pagini: 242

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture

Recenzii

“In Courtly and Queer: Deconstruction, Desire, and Medieval French Literature, Charlie Samuelson situates queerness not in the margins, in lesser known or read texts, but rather at the centre of the canon of French courtly poetry. … through intricate and compelling close readings, he draws out the ‘deviant poetics and sexual politics’ at the heart of courtly literature.” —Moss Pepe, Forum for Modern Language Studies

“Courtly & Queer ultimately demonstrates what queer scholarship still has to gain from a deconstructive approach … The book’s understanding of queerness is valuable not only for deconstructing the libidinal investments of courtly texts, but also for destabilizing the generic categories and (often teleological) historical narratives into which such texts are inserted. This is smart scholarship that repays careful reading and that gives literary historians, as well as queer medievalists, important food for thought.” —Emma Campbell, H-France Review

“The title, though accurate in a comprehensive sense, does not really capture the excitement that this book conveys or the full complexity of its arguments … Samuelson rubs text against theory so convincingly that their interaction seems natural, essential, almost eerily in sync. The writing is breezy, witty, conversational … This is a book well worth reading and then reading again.” —Bill Burgwinkle, French Studies

“Samuelson is a first-rate medievalist—intellectually rigorous and theoretically sophisticated in ways that enable him to push back against rigid disciplinary constraints and stale orthodoxies. His engagement with verse romance and dits as sites of rhetorical, fictional, and libidinal deviation will inspire scholarly debate for years to come.” —Noah D. Guynn, author of Pure Filth: Ethics, Politics, and Religion in Early French Farce

“Courtly and Queer is masterfully written, ambitious, and provocative. Samuelson’s integration of queer theory into French medieval scholarship bears exciting new implications for questions of authorship, metadiscourse, poetics, and narrative.” —Deborah McGrady, author of The Writer’s Gift or the Patron’s Pleasure? The Literary Economy in Late Medieval France

Notă biografică

Charlie Samuelson is an Assistant Professor of French at the University of Colorado–Boulder.

Extras

In the opening section of her brilliant Queer/Early/Modern, Carla Freccero reflects on the meaning of the slashes in the title. These slashes “interrupt” formulations like “early modern”; they “force a pause” on each term and on its relation to the others (3). “Inarticulable though they may be,” they also allow for directional ambiguity, which is at the heart of her project, as it cannot be clear which terms are acting on each other—or how (3). “The slash between early and modern,” she thus writes, “allows me to admit considerable uncertainty about the question of whether what I do in queering ‘back then’ has anything to do with ‘back then’ or not” (4; original emphases).

Courtly and Queer is also, it seems to me, a book of slashes. There are those I have most advertised: courtly/queer, of course, and verse romance/dits. And there are others. As concerns the corpus: High/Late Middle Ages. As concerns the methodology: language and poetics/gender and sexual politics, even deconstruction/queer theory. Certain chapters are largely about slashes, too: the chapter on metalepsis, those that describe the knotty relations between narrative levels or segments; or the chapter on lyric insertion, those between the lyrics and the surrounding texts. No doubt the relationship between the chapters also takes a similar form. Indeed, studies of the interplay between narrative segments and levels, on the one hand, and lyric pieces and surrounding verse narratives, on the other, come together—in their methodology and ambitions—but are not the same thing. Likewise, the ambivalent reflexivity of the always-already reflexive subject intersects—in its emphasis on the illogical, the messy, the irresolvable, and the excessive—with the vicious irony of “the drive,” without being identical to it. Arguably the most important slashes are, moreover, the countless fine ones within readings: not only those where I am considering different moments in texts alongside one another but also the slashes that position my reading of a given instance in relation to those of other critics.

...

It is nonetheless important to insist on how, on the whole, this book’s engagement with what I am here calling slashes is in opposition to critical modes that privilege our distance from the past. As mentioned, this book resists the temptation of what Fradenburg has called “discontinuist historicism,” “or the idea that different periods of time are simply and radically other to one another” (87). In the spirit of exciting work on “post-historicism” in medieval English studies, as well as Freccero’s volume or Dinshaw’s work, I am wary of approaches where the refrain can seem to be as follows: everything must be contextualized as carefully and locally as possible, and anachronism is the ultimate sin. As Maura Nolan warns, “It is possible to be influenced by a kind of ‘pastism’—a refusal to see those moments at which the Middle Ages seem shockingly modern, out of step with the ‘medieval’ and surprisingly or painfully resonant with contemporary preoccupations” (68). Positing a fundamental difference between the medieval and the modern should, furthermore, give particular pause when it comes to sexuality studies; for heteronormativity’s total fixation on difference when it comes to the gender of object-choice—and its tendency, as Edelman and others have shown (e.g., No Future 57–63), not to critically interrogate this notion of difference on which it claims to rely—has been so immensely problematic.

Yet, as I have insisted at various points, the juxtapositions of elements at the heart of this book do not reflect relations of identity either. There is an important difference between conceiving of the relation of courtliness and queerness, for instance, in terms of the slash (courtly/queer) rather than an equal sign (courtly=queer). (And the “and” in this book’s title leaves crucial room, in my view, for the persistent ambiguity of the relations between courtliness and queerness). The slash and the equal sign even seem to me incompatible, since positing a relationship of identity between terms is in contrast to this book’s understanding of queerness, according to which, to quote Edelman, “queerness can never define an identity; it can only ever disturb one” (No Future 17).

Courtly and Queer is also, it seems to me, a book of slashes. There are those I have most advertised: courtly/queer, of course, and verse romance/dits. And there are others. As concerns the corpus: High/Late Middle Ages. As concerns the methodology: language and poetics/gender and sexual politics, even deconstruction/queer theory. Certain chapters are largely about slashes, too: the chapter on metalepsis, those that describe the knotty relations between narrative levels or segments; or the chapter on lyric insertion, those between the lyrics and the surrounding texts. No doubt the relationship between the chapters also takes a similar form. Indeed, studies of the interplay between narrative segments and levels, on the one hand, and lyric pieces and surrounding verse narratives, on the other, come together—in their methodology and ambitions—but are not the same thing. Likewise, the ambivalent reflexivity of the always-already reflexive subject intersects—in its emphasis on the illogical, the messy, the irresolvable, and the excessive—with the vicious irony of “the drive,” without being identical to it. Arguably the most important slashes are, moreover, the countless fine ones within readings: not only those where I am considering different moments in texts alongside one another but also the slashes that position my reading of a given instance in relation to those of other critics.

...

It is nonetheless important to insist on how, on the whole, this book’s engagement with what I am here calling slashes is in opposition to critical modes that privilege our distance from the past. As mentioned, this book resists the temptation of what Fradenburg has called “discontinuist historicism,” “or the idea that different periods of time are simply and radically other to one another” (87). In the spirit of exciting work on “post-historicism” in medieval English studies, as well as Freccero’s volume or Dinshaw’s work, I am wary of approaches where the refrain can seem to be as follows: everything must be contextualized as carefully and locally as possible, and anachronism is the ultimate sin. As Maura Nolan warns, “It is possible to be influenced by a kind of ‘pastism’—a refusal to see those moments at which the Middle Ages seem shockingly modern, out of step with the ‘medieval’ and surprisingly or painfully resonant with contemporary preoccupations” (68). Positing a fundamental difference between the medieval and the modern should, furthermore, give particular pause when it comes to sexuality studies; for heteronormativity’s total fixation on difference when it comes to the gender of object-choice—and its tendency, as Edelman and others have shown (e.g., No Future 57–63), not to critically interrogate this notion of difference on which it claims to rely—has been so immensely problematic.

Yet, as I have insisted at various points, the juxtapositions of elements at the heart of this book do not reflect relations of identity either. There is an important difference between conceiving of the relation of courtliness and queerness, for instance, in terms of the slash (courtly/queer) rather than an equal sign (courtly=queer). (And the “and” in this book’s title leaves crucial room, in my view, for the persistent ambiguity of the relations between courtliness and queerness). The slash and the equal sign even seem to me incompatible, since positing a relationship of identity between terms is in contrast to this book’s understanding of queerness, according to which, to quote Edelman, “queerness can never define an identity; it can only ever disturb one” (No Future 17).

Cuprins

Acknowledgments Introduction Verse Romances and Dits, Poetic and Sexual Indeterminacy Chapter 1 Reflexive, Ambivalent, Queer Subjects Chapter 2 Medieval Metalepsis: Queering Narrative Poetics Chapter 3 On Sameness, Difference, and Textualizing Desire: Queering Lyric Insertion Chapter 4 Queer Irony in Chrétien de Troyes and Guillaume de Machaut Coda Slashes Bibliography Index

Descriere

Recasts queerness in medieval French romances by juxtaposing key genres for the first time, revealing how their literary sophistication overlaps with modern conceptions of queerness.