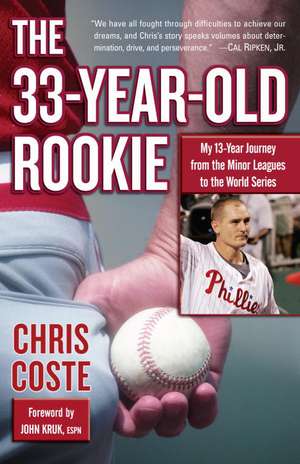

The 33-Year-Old Rookie: My 13-Year Journey from the Minor Leagues to the World Series

Autor Chris Coste John Kruken Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2009

Preț: 105.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.09€ • 21.82$ • 16.88£

20.09€ • 21.82$ • 16.88£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345507037

ISBN-10: 0345507037

Pagini: 225

Ilustrații: 8-PG B&W INSERT ON TEXT STOCK

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345507037

Pagini: 225

Ilustrații: 8-PG B&W INSERT ON TEXT STOCK

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Chris Coste was an All-American at Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, and played five seasons in various independent leagues before finally getting a shot with the Cleveland Indians’ organization in 2000. From there, he moved to the minor league systems of the Boston Red Sox, Milwaukee Brewers, and Philadelphia Phillies. Coste was awarded the 2006 Dallas Green Award for Special Achievement and the 2007 Media Good Guy Award in the Philadelphia area. He lives in Fargo, North Dakota, with his wife, Marcia, and their daughter, Casey.

www.christcoste.com

From the Hardcover edition.

www.christcoste.com

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

Spring Training 2006

SPRING training did not get off to a promising start. And this was even before I so much as strapped on my shin guards.

I arrived in Clearwater, Florida, in February 2006 with the rest of the pitchers and catchers for my second spring with the Phillies. My only hope to put myself on the club’s radar, as in each of the other four spring camps I’d attended, was to prove that I could catch at the major-league level. Going in, I knew that Philadelphia had its two catchers in Mike Lieberthal and Sal Fasano, and there was nothing I could do to take either one’s spot on the twenty-five-man roster for opening day. The most that a player in my position could hope for was to make enough of a positive impression that if someone went down during the season, I might get called up.

After pulling into the parking lot of the Hampton Inn in our rental car, Marcia, Casey, and I got out and began unpacking the car. I went straight to the trunk for the heavy bags and was dubiously greeted by one of the small Florida birds. I felt something soft and wet hit my head and couldn’t believe what had just happened.

“Mommy!” yelled Casey with exhilarating laughter in her voice. “Did you see that? A birdie just flew by and pooped on Daddy’s head!” My sixyear-old daughter could barely contain her laughter at seeing her big and strong daddy getting pooped on the head by a tiny bird. Marcia didn’t know whether to laugh or not because she was unsure how I would react. I normally have a good sense of humor, but to have a bird poop on your head certainly is not a pleasant experience. Fortunately, seeing the joy and laughter on Casey’s face made me instantly realize that it was funny.

You have got to be kidding me, I thought to myself. My first instinct was that a bird pooping on my head was not a good way to begin spring training.

No sooner had we settled into our hotel room than I received a phone call from Steve Noworyta, the Phillies’ director of minor-league operations. Simply put, he’s like the general manager of the organization’s minor-league teams and oversees all of its minor-league players.

“Hi, Chris,” he said in a concerned tone. “Are you in Clearwater already?”

“Yes.” Why wouldn’t I be? I thought.

“Oh . . .” He sighed an ominous sigh. “Well, I guess we had a bit of a miscommunication. We didn’t want you to show up with the pitchers and catchers, we wanted you to show up next week with the position players. As of right now, it looks like you will play mostly first or third base in triple-A. But since you are already here, I guess you can show up tomorrow and help catch some bullpens and stuff like that.”

To put it mildly, I was pissed off. I had hoped to prove to anyone who would pay attention that I was a good catcher. I knew it, my teammates knew it, and virtually every pitcher who’d ever thrown to me always had great comments regarding my catching ability. By no means was I another Johnny Bench, but they always praised my game calling, my soft hands, my ability to catch the low pitch for a strike, and how I always gave a great target. Over the years, many pitchers had remarked, “Chris, I stare in at your glove, and it’s like I can’t help but throw a perfect strike into it!”

In fact, many of my batterymates had gone to the manager and requested that I catch them in their next start. All catching instructors preach the importance of earning the pitchers’ confidence. “A catcher may be able to hit great, block every ball, and throw every guy out trying to steal, but the only thing that matters is if the pitching staff likes throwing to him,” they’ll stress. “If a pitcher insists that you catch him, that is the best compliment you can receive. And it is that kind of catcher that will not only get to the big leagues but stay there.”

Well, I was that kind of catcher. So why hadn’t I made it?

One reason, I’m pretty sure, was that my ability to play other positions actually undermined my career, in a way. What was my best position? Catcher? First base? Third base? It was always a mystery to them. I always considered myself a catcher who could play elsewhere if needed. However, the decision makers inevitably mistook me for a utility man who could play multiple positions–with catching being just one of them. It seems similar, right? But in the world of professional baseball, there’s a huge difference between the two perceptions. The term utility player tends to refer to guys who play shortstop and second base, maybe third base, too. No team will put its trust in a catcher who is not primarily a catcher.

So to hear that the Phillies had no plans for me to catch during spring training made no sense to me. And they wanted me at first base, of all positions? They had to be kidding. Ryan Howard, the reigning NL Rookie of the Year, played there. All he did in 2005 was hit .288 with 22 homers and 63 RBIs in just half a season.

I hung up the phone in disgust.

“What did you expect?” my wife asked. “Did you really think things were ever going to be easy for you? This is totally par for the course.”

“I really hoped the Phillies would be different,” I replied. “And I’m thirty-three, Marcia. Time is more than running out. If they won’t give me the chance to prove I can catch, I will never make it. Catching is my only hope. They will never call me up as an infielder, especially not at first base.”

No one understood what I had gone through more than Marcia. As many times as I had received great comments from pitchers over the years, oddly enough, she also received the same kind of comments from pitchers’ wives. “Is your husband catching tomorrow?” a wife would ask. “My husband is pitching tomorrow and he loves it when Chris catches.” She heard things like that on a regular basis.

Her response was usually the same as my response to the pitcher. “He loves to catch, but your husband needs to tell that to the manager or the pitching coach–they are the only ones who will listen,” Marcia would say. I had almost taught her word for word what to say when a wife would say these things to her. The typical response from the wife was that her husband had gone into the manager’s office on several occasions and told him that I should be catching.

HERE’S how you know you’re a long shot to crack the opening day roster: When I reported to training camp, I was handed a uniform with a big red 67 on the back. Generally, the higher your number, the lower your status. I also took note that my locker was on the “hopeless” side of the locker room with all the other players destined for the minors. Or oblivion.

I decided to use my frustration as motivation. It may have been only spring training, but I approached every catching drill as though I were preparing for the World Series. Just as important, each and every day I was in Charlie Manuel’s ear, reminding him that catching was my best position. He knew I could hit: In 2002, when he was managing the Indians, I batted .318, 8 HR, 67 RBI for the triple-A Buffalo Bisons and was named team MVP; the previous spring, Charlie’s first as Phillies skipper, I hit at a .313 clip. Now I had to prove to him that I was good defensively. “Just keep your eyes open,” I’d say before morning workouts. “I promise I will surprise you.” He wouldn’t reply, just smile and nod, as if to say, “Okay, go prove it.”

One other factor would make this spring training difficult: It was the first spring that I would be mostly on my own, as Marcia and Casey had to leave the following week. In previous years, they had accompanied me throughout the entire baseball season. But with Casey now in first grade, she could no longer miss so much school. We would all have to try to get used to seeing each other for short stints up until school let out in June.

Through the first weeks of spring training, I knew I was making a bit of a statement. Three days before our first official spring training game, against the New York Yankees, the team’s main catching instructor, Mick Billmeyer, approached me with some positive words. “Coastey,” he said, “after watching you catch bullpens, seeing you in our catching drills, and going by what the pitchers are saying about you, I have been telling Charlie every day that I think you can catch in the big leagues. He also asks about you every day and tells me to keep an eye on you because he wants to know how good of a catcher you really are. He knows you can hit, and he definitely wants to give you a shot at catching in some spring training games. So be ready, you might actually get a chance to impress him.” Mick, a former catcher, seemed empathetic, perhaps because he’d languished in the minors for eight seasons before turning to coaching in the 1990s.

“Also,” he continued, “Carlos Ruiz will be gone for a while to catch for Panama in the World Baseball Classic, so that should also allow you to slip in and catch some innings.” Ruiz had a lock on the starting catcher’s job at Scranton/Wilkes-Barre and figured to put in a lot of time behind the plate during the spring. With him away to participate in the first-ever international baseball tournament, I’d get a few extra innings to show what I could do.

That brief exchange with Mick Billmeyer improved my outlook dramatically. Whether it was a coincidence or not, later that day I really put myself on the map as far as the Phillies were concerned. I got a chance to take live batting practice off Scott Mathieson, a hard-throwing righthander from Vancouver whose fastball had been clocked as high as ninety-nine miles an hour in double-A the previous season. He’d just turned twenty-two and was viewed by many as a can’t-miss prospect. Scott had been tossing bullpen sessions in preparation for the World Baseball Classic, slated to begin the first week of March; I was selected as one of the hitters to face him in his final practice before leaving to join his Canadian teammates. (Several other members of the Phillies would be going to the games, held in the U.S., Japan, and Puerto Rico, including Chase Utley, Philadelphia’s representative on the American team.)

Excited at the opportunity to face live pitching, I was also a little nervous–especially after I glanced behind the batting cage and saw Charlie Manuel standing next to most of the Phillies’ brain trust. There was new general manager Pat Gillick; Ruben Amaro Jr., the assistant GM; and Gillick’s special advisor, Dallas Green, the man who’d managed Philadelphia to its only World Championship, back in 1980. If I was going to open some eyes, this would definitely be an opportune moment to shine. Maybe my only moment.

As I stepped into the batter’s box, catcher Dusty Wathan lifted up his mask and said with a sigh, “Don’t you just hate these live batting practice sessions? Especially against a guy with a fastball like Mathieson’s?”

“Not really,” I said. “I kind of like this stuff.” Most hitters dreaded taking live batting practice off their teammates, for a couple of reasons. One, they don’t like to compete against one of their own, and, two, suddenly the ball is coming in much faster at a time when their reflexes and bat speed aren’t ready for gamelike activity. Me, I’d always enjoyed it, in part because I was good at it. Batting practice is the only time when the pitcher tells the hitter what pitches are coming. Also, there’s really nothing to lose. Either you hit the ball hard, impressing everyone; or you don’t hit the ball hard, and people think you’re not really trying because you don’t like to hit off your team’s own pitchers.

Scott’s first pitch blew by me at around ninety-five miles per hour, according to the radar gun, but high and out of the zone. As it snapped into the catcher’s mitt, I heard Charlie Manuel’s distinctive West Virginia drawl: “How ’bout that Scott Mathieson? He’s throwin’ some heat today. Be careful, Coste!”

I looked back at Charlie, and in my best southern accent, said, “Gotta hit, Charlie,” one of his pet phrases. He’d spent several years as the Cleveland Indians’ hitting coach, and he loves guys who can hit. He’ll walk through the clubhouse, saying to all the hitters, “Gotta hit, son! Gotta hit!”

“All right, then,” he replied, a wide grin on his face. “Go hit him, son! Gotta hit!”

I have always prided myself on being able to hit any fastball. If I know it’s coming, I’ll catch up to it, regardless of its speed. As Mathieson released the next pitch, I gripped the bat tight and let it fly, rocketing the ball at least fifty feet over the fence in left-center field. “How about that Chris Coste!” Charlie exclaimed with a small laugh under his breath. “Be careful out there, Mathieson!”

Next Scott hummed a fastball middle-in, and once again I brought the bat around and sent it over the left-field wall, this time by some seventy-five feet. Dallas Green, once a Phillies pitcher himself, yelled out, “Wow, Charlie, it looks like Coste brought his quick hands with him this year!”

“Well, he did hit twenty bombs last year in Scranton,” the manager responded. I whipped around and looked at Charlie, pleasantly surprised that he knew my stats. The twenty home runs in 2005 was a career high for me. He gave me a quick wink, and I stepped back into the batter’s box. Before I was finished, I’d cracked several more solid hits, including a few that disappeared over the fence. The Grapefruit League games, set to start in a few days, were the real tryouts, of course. Still, I drove back to the Hampton Inn that afternoon satisfied that I’d forced the team’s decision-makers to notice me.

Two days later we held an intrasquad game so that some of the pitchers could get in an inning of work against hitters in a gamelike setting, and the rest of us could get acclimated to game-speed situations. We were all looking forward to the games, which would put an end to days spent practicing the same drills over and over: blocking balls in the dirt, throwing to bases, fielding bunts and pop flies. Five minutes before the intrasquad contest, I stood in the dugout, expecting to watch it from the bench. Gary Varsho, the bench coach, came up to me and asked, “Hey, Coastey, do you have your first baseman’s mitt out here?” On my own time at the end of each day, I’d been taking infield practice with some of the minor-league coaches in camp.

“I’ve got all my gloves, Varsh,” trying to remind him how versatile I was.

“Well, go get it. You’re playing first base.”

“Um... right now?” I assumed he meant that I would fill in at first toward the end of the game.

“Yes, right now!” he answered.

To be honest, I felt a bit startled and unprepared. Ryan Howard was scheduled to play first base. Ordinarily, he would have gotten two or three at-bats, then maybe I or someone else would take over in the sixth or seventh inning. I unloaded a mouthful of sunflower seeds–the ballplayer’s chewing tobacco of the twenty-first century–scrambled to find my hat, and yanked out my dusty old first baseman’s mitt from the bottom of my catcher’s bag. I searched around for some sunglasses, then out to first base I trotted, excited not to be sitting on the bench for three hours like the other minor leaguers from my side of the clubhouse.

My first at-bat, against Phillies ace right-hander Brett Myers, 13—8 the year before, brought a harsh reminder of the difference between facing a hot phenom and an established major-league pitcher. Unfortunately, I was a bit tentative and got around late on a slider, flying out weakly to short right field. While running back to the dugout, I chastised myself for not being my normally aggressive self. The second time up, however, I attacked the ball and doubled off the wall in left-center. Just like that, my confidence surged. Today was going to be a good day; I could feel it.

In the fifth inning, I came up with a runner on second and nobody out. Aaron Myette, another hard-throwing Canadian, stood on the mound. He’d signed with the Phillies after spending the previous season in Japan. Like me, the tall right-hander was fighting to make an impression and full of the same intensity.

I looked down to third-base coach Bill Dancy for the sign. He didn’t flash any–just yelled at the top of his lungs, “Okay, Coastey, do your job!” With a runner on second and no one out, “do your job” meant to hit the ball to the right side or deep to the outfield so I could at least move him to third. This can be a very difficult situation for a right-handed hitter, especially against a pitcher with a good fastball like Myette.

Knowing where I was trying to hit the ball, he threw his best fastball inside for a ball. I looked down at Dusty Wathan and said, “I am really not a big fan of the ‘get the runner over’ situation.” He just looked up at me and smiled.

I dug back into the batter’s box and waited for the next pitch, knowing that another inside fastball was coming. This time the ball wandered over the plate, and I windmilled it. Crack! Off it sailed, high and deep over the wall in left. As I trotted around the bases, a voice from the dugout yelled, “Somebody on that!” a common expression after someone hits a home run in minor-league camp. It means “Retrieve that ball!” During a typical minor-league spring training, players who are not part of the game will be assigned to either home run or foul ball duty. Remember, there aren’t any fans in the stands to toss it back. But since this was major-league spring training, “Somebody on that” was a joke used by minor-league lifers like me to lighten the mood.

Rounding third, I slapped a high-five with Bill Dancy. “Attaway to get the runner over!” he said jokingly.

I whacked another double in my fourth at-bat. So when I stepped up in the ninth inning, my day looked like this: 3-for-4, two doubles, one home run, four runs batted in. I need to finish strong, I thought to myself. On the second pitch I nailed an opposite-field single to right, driving in another run, solidifying me as the unofficial player of the game.

A bevy of Philadelphia reporters, down south for spring training, mobbed me as I entered the clubhouse, making for an odd scene. Ordinarily they would be found on the other side of the room, huddled around the locker of a Phillies star like Howard or Utley, but they were thrilled to have an interesting story emerge so early in camp. My mind raced as I answered their questions.

I wondered if any Japanese scouts had been in the stands. Damn, if they’d seen me, I probably would have been offered a contract for a half million dollars. Well, I consoled myself, at least Charlie Manuel was paying attention, and Pat Gillick, too. I hope Pat was watching.

I came to find out later that day that Ryan Howard had been sickened by food poisoning. Although I certainly would never wish illness or injury on anyone, his absence had opened the door for me, putting me on a path to an eventual unforgettable and amazing spring.

The next day we traveled to nearby Tampa to face the New York Yankees for our first official game. Replacing Howard at first base in the sixth inning, I flied out to right off the sidearming veteran lefty reliever Mike Myers. I got one more chance to make a statement in the top of the eighth, this time with twenty-one-year-old J. B. Cox on the mound. The highly regarded Texan boasted a wicked two-seam fastball that dropped off the table and, like a good two-seamer, induced countless ground balls. I took the first pitch, a two-seamer, for a ball. Normally I would have swung, but I wanted to get a good look at it first. Cox didn’t want to fall further behind in the count, so he laid the next pitch right down the middle of the plate. Big mistake. My first memory after making contact with the ball was almost missing first base as I watched the left fielder run out of room while the ball sailed over his head for a home run. My next memory was thinking that Yankees skipper Joe Torre, one of the winningest managers in baseball history, was watching me, Chris Coste, round the bases. And my childhood hero, Reggie Jackson–Mr. October!–was at Legends Field in his capacity as spring training consultant. Maybe he saw it, too. Then I reminded myself that I needed to be more concerned about making an impression on Charlie Manuel than on Joe Torre.

We went on to win the game 6—3, and as I entered the clubhouse afterward, pitcher Ryan Madson gave me a high five. “That was awesome!” he said. “Keep it up, man, stay hot!”

The next day we faced the Yankees again, only this time at Bright House Networks Field, our home stadium in Clearwater. Once again I took over for Ryan Howard at first base in the sixth inning. With the score tied at ten apiece in the bottom of the ninth, I came to the plate amid a mix of cheers and disappointed jeers. We had two men out and runners on first and second, and it’s safe to say that the remaining Phillies fans in attendance would much rather have seen Ryan Howard come to the plate with the game on the line.

“Hey, Charlie, put Howard back in the game!” yelled an angry fan. “This Cawstee guy has no shot! Besides, we didn’t pay to see guys that have number sixty-seven on their back!” This pissed me off! Not because this fan had no faith in me but because he’d mispronounced my name, calling me “Cawstee” instead of “Coast.” Silent e. Presumably, Ryan Howard has never encountered this problem. But it’s something that has motivated me my entire baseball life. I can remember how embarrassed I felt the first time I heard my name mangled over a loudspeaker when I was fourteen. Back then I promised myself I would become the best baseball player who ever lived so that everyone in the world would know how to pronounce Chris Coste.

On the flip side, I could somewhat understand where the fan was coming from. I had replaced Howard earlier in the game after he had gone 4for-4 with two long home runs and five RBIs. If I were a fan, I too would have had a lot more confidence in Howard than a nobody with 67 on his back. Fortunately, after swinging and missing at the first pitch, I drilled the next pitch into the left-field corner for a game-ending RBI single.

The first person to greet me back in the clubhouse was center fielder Aaron Rowand. “Dude, you are unbelievable!” he exclaimed. “I was telling everyone that the game was over as you walked to the plate. If there was one guy that was guaranteed to get a hit and end the game, it was you!”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Because you are locked in, and other than Howard, you are our hottest hitter.” For a guy like Aaron Rowand to have that much confidence in me was incredibly uplifting. He was the center fielder for the 2005 World Champion Chicago White Sox before coming to Philadelphia in a big winter trade for popular slugger Jim Thome. Maybe the biggest off-season acquisition for the 2006 season, Phillies fans would put a lot of pressure on him.

Once again, I was besieged by reporters at my locker. They knew I had little or no chance of making the team, but they were going to ride this feel-good story as far as it would take them. That day’s headline on the team website read “Coste’s Single Lifts Phils over Yanks.” Quite a compliment considering Ryan Howard’s five-RBI day and Rowand’s first homer in a Phillies uniform. Best of all, the manager was starting to take notice, with Charlie telling the papers, “He’s got it going. You can tell he loves to play baseball.”

Two days later, we faced the National League champion Houston Astros in Clearwater. After I sat on the bench for most of the game, Charlie told me before the ninth inning to be ready to pinch hit in the event we could get a runner into scoring position. I was excited to hear this because it meant he had confidence in me to come up big in a clutch situation. Well, we were down by two runs going into the inning, so clutch is what he was looking for. After scoring a run early in the frame, I came to the plate with two outs and a runner on second base. This is a golden moment, I told myself as I walked to the plate. If I can get a hit here, who knows what could happen. I was having a good spring to that point, and already had one walk-off base hit. Now I had to show everyone, especially Charlie, that it wasn’t just a fluke, that I was indeed a clutch hitter.

Not wasting any time, I stroked the first pitch I saw up the middle to tie the game at three. We went on to win it in the bottom of the tenth, bringing our spring record to 4—0. My average stood at .700. Make that a gaudy .700, as sportswriters are fond of saying.

After the game my new friends from the press paid yet another visit to my locker. We joked about how they’d never spent so much time on the minor-league side of the clubhouse. Then one of them said, “You’ve been having a great spring so far. With David Bell suffering from a bad back and unlikely to be ready for the season opener in April, how do you like your chances of making the team?” Bell was the Phillies’ thirty-threeyear-old starting third baseman. I had no idea that he was out of action. Not that you ever want to see a teammate get hurt, but if he wasn’t going to be ready for the start of the season, my chances of making the team definitely went up, still a long shot, but seemingly rising by the day.

A few days later I was sitting at my locker when Charlie Manuel told me I was finally going to catch against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. Better still, I’d be giving the signs to veteran right-hander Jon Lieber, a seventeen-game winner who carried a lot of clout with the coaches. He approached me right before the game.

“Hey, bro, I was hoping you were going to catch me today. Let’s have a good day.” I’d caught him in a few bullpen sessions earlier in the spring, and he went on to tell me that he liked the way I caught the ball and my big setup. “It feels like I can’t help but throw it to the middle of your mitt,” he said. I actually had to suppress a giggle, because I’d heard that same line, almost word for word, from many other pitchers in the past.

“Well, feel free to tell that to Charlie and Dubee!” I replied. Dubee referred to Rich Dubee, the Phillies’ pitching coach.

“Believe me, I have,” said Lieber. “Several of us have told both of ’em the same thing.”

“That’s awesome. I have fought my whole career to prove I am a catcher, and the pitchers have always said those kinds of things. Unfortunately, nobody has ever listened.”

“Well, Charlie will listen.”

Although Tampa Bay edged us out 4—3, scoring two in the ninth to take the lead, I had a good day. I went 1-for-2 against young fireballing lefty Scott Kazmir, but more important, Lieber threw great and I had a great day catching, even throwing out Ty Wigginton trying to steal second base in the first inning. I would have also thrown out another guy in the third inning, but the umpire, having clearly missed the play, called the runner safe at second.

Charlie Manuel lifted me at the start of the sixth. “Damn, Coastey, you can catch, son!” he exclaimed.

“Damn right! I’ve been telling you that all spring!” I had a big smile on my face, and Charlie flashed me his patented wink.

Still, several days would pass before I received a second opportunity behind the plate, and then only in a minor-league spring training game. Ordinarily, I wouldn’t have been too excited to see action against the Toronto Blue Jays’ triple-A team, except that I’d be handling another one of the Phillies’ top starters, Cory Lidle, who needed to get in some work. He’d posted a 13—11 record in 2005. If I could impress him with my catching ability, I’d open some more eyes among the decision-makers.

Following Lidle’s five shutout innings, the right-hander pulled me aside and had some great comments. “You know, Coastey, I had no idea you were such a good catcher. I really thought of you as an infielder. I am amazed! With the way you hit, how are you not in the big leagues somewhere–at least as a back-up catcher? Not only that, but we were on the same page all day long; I shook you off maybe only twice. You can catch me anytime!” That was the best comment of all. Cory had a repertoire of five pitches, which made it incredibly difficult at times to figure out which one he wanted to throw. I must have developed a psychic ability that day, because he seemed to throw every pitch I called.

“Well, if you are serious, feel free to tell that to Charlie,” I said. “For him to believe in me as a catcher, he has to hear that kind of stuff from his pitchers.”

“Absolutely, I will tell both Charlie and Dubee.”

I knew this was the start of something good. Cory was not the kind of guy to keep his mouth shut; on the contrary, he always spoke his mind. Sometimes, in fact, his candor got him into trouble. The next morning, he called me over to a table in the clubhouse, where he was polishing off his usual breakfast from Chick-fil-A.

“Hey, Coastey, I just talked to both Charlie and Dubee, and I told them exactly what I told you yesterday.”

“How did they take it?”

“They joked about how they’re getting tired of all the pitchers saying the same thing. Apparently they have been hearing the same thing about your catching ability from a lot of the pitchers. It’s not just me and Lieber.”

It had been quite a spring so far. With several of the pitchers wearing out Charlie’s and Dubee’s ears, I knew I would earn more opportunities to impress. And with David Bell’s back still acting up, there was likely to be an open roster spot. I had gone from an anonymous number 67 suiting up on the minor-league side of the clubhouse to a guy with a legitimate shot at making the opening day roster for the Philadelphia Phillies. But the best was yet to come a day later against the Pittsburgh Pirates.

After sitting in the hot sun out in the bullpen for the first six innings, I took over at catcher for Mike Lieberthal in the seventh. Earlier in the day I had come across some bats left behind by a former Phillies outfielder, Jason Michaels, who’d been traded to Cleveland shortly before the start of spring training. Normally I was fanatical about using only my model from Louisville Slugger, but I took Jason’s bats in my hands and just knew they had hits in them. Knew it! They felt great–even looked great, with a dark-flamed finish that gave them a cool and unique look.

Now, like many ballplayers, I can be superstitious. Maybe it’s because we play a sport where failing to get a hit seven times out of ten is good enough to land you in the Hall of Fame, so we figure we can use all the help we can get.

For example, I’ll often smell my bat after I hit a foul ball. Why? I suppose it’s because I used to go to the lake a lot while growing up in Minnesota. And I just love the smell of wood burning, like from a campfire; I associate it with my childhood. Sometimes if you foul off a baseball that’s hurtling toward you at ninety, ninety-five miles per hour, the friction produces that same burnt-wood aroma. Or maybe it’s the smell of the leather. Or both. Anyway, one time early in my career, I just got a piece of a fastball, then held the bat up to my nose. For a moment, there I was, a kid again, back at West McDonald Lake in Minnesota. I proceeded to send the next pitch into the bleachers for a grand slam. Ever since then, I will often sniff my bat, partly out of superstition and partly because I just plain like the smell.

Back to Jason Michaels’s leftover lumber. In the bottom of the seventh inning against the Pirates, I stepped up to the batter’s box with one of his bats. We trailed by four runs and had a runner on first. On a 1—0 count, I sent the next pitch deep over the wall in left center, cutting the deficit to 8—6.

If you’ve ever listened to a Phillies game on the radio, you’re probably familiar with the resonant voice of Harry Kalas, the team’s play-by-play announcer since 1971. From the day I signed with the organization in January, one of my goals was to hear the Hall of Fame broadcaster call one of my home runs. With the crack of the bat, here’s how he called it: “Ooooh, watch that baby... deep to left field... and that ball is outta here! Chris Coste, a two-run home run, and it is now an eight-to-six game as the Phillies come fighting back.”

If the game had ended right there, I would have been thrilled. But in the bottom of the ninth, with our team still trailing by two, I was due up fourth. We had the tying run on first and one out as Ryan Howard, getting a day of rest, was announced as the pinch hitter. The reigning NL Rookie of the Year had already launched seven home runs that spring. Unfortunately, he lofted a high fly ball that just missed going out and tying the game. As soon as the ball parachuted into the outfielder’s glove, the capacity crowd of eight thousand started making its way for the exits.

Wait a minute, I thought to myself. I hit a two-run homer just two innings ago! We still have one out left. How can all these fans leave?

Meanwhile, out in the bullpen, catching instructor Mick Billmeyer and minor-league catcher Dusty Wathan were prognosticating my future. As they told me after the game, Dusty remarked, “Another home run by Coastey would be nice right now.”

“If he hits another homer here, he can almost guarantee himself a spot to go north with the team,” replied Mick.

“Well, if he hits another home run here, not only will he guarantee himself a spot on the team, he can probably pilot the team plane to Philly.”

“Giddyup with that!”

As the count made its way to 3—1, I called time out to gather my thoughts and to clear my eyes. I’d noticed that the wind, which had blown out to center field for most of the game, was now coming in from left field. It would be difficult to pull the ball over the left-field wall against the wind; I’d be better off trying to drive the pitch into the right-field gap. Maybe get a double, which would put the tying run in scoring position. I can also remember telling myself not to chase ball four–after all, I was the tying run and if I could at least get on base it would bring the winning run to the plate. My final thought was how much I despised being the guy who made the last out of the game. In my mind, having to walk off the field as the batter who made the last out was one of the most humiliating situations a ballplayer can be in.

In dramatic fashion, I nailed the ball on a line to deep left field and over the left fielder’s head. To my surprise, it sliced through the wind and cleared the left-field wall by the slimmest of margins, landing safely in the Pirates’ bullpen. Once again, here is how Harry Kalas called the action:

“There’s a long drive, and this game is gonna be tied...I believe ... yes! Into the bullpen! How about Chris Coste! A two-run home run in the ninth inning with two outs. Coste has had two at-bats, two homers, four runs batted in! Amazing!”

As I touched home plate and trotted toward the dugout, I thought happily, There is no way they can keep me off the team now! A barrage of high fives from my teammates greeted me. They all knew the kind of spring I was having and the significance of the situation. If there was any doubt that I was the front runner for David Bell’s open roster spot, they had all been erased after that game.

For the first time in a week, my friends from the Philly media were back around my locker. “I didn’t think you guys were ever going to come back here again,” I joked. After they got their quotes and drifted off, reliever Clay Condrey planted himself in front of me with an angry expression on his face. Like me, he was a journeyman ballplayer; in fact, he’d signed with Philadelphia the same day that I did. Clay was also one of my spring training roommates.

We both broke up laughing. Without his saying a word, I knew what was on his mind: We’d planned to go golfing with our other roommate, pitcher Brian Sanches, later that afternoon; my two home runs sent the game into extra innings, causing us to miss our scheduled tee time.

“I’m so sorry,” I said sarcastically, “I forgot all about our tee time. If I’d remembered, I never would have hit both those home runs today! I would have only hit one and then maybe only a triple in my other at-bat.”

“A triple? You haven’t hit a triple since the Clinton administration,” Clay retorted.

“Okay, maybe a double, and then I would have gotten thrown out trying to stretch it into a triple.”

“That sounds better. Seriously,” he added, “you’d better be careful, because if you keep messing around like this and continue to get all these big hits, you might actually make this team. And guys with number sixty-seven don’t make big-league teams.”

I was still on a high the next day when Charlie Manuel put me in at first base in the eighth inning against the Cincinnati Reds. I’d have just one at-bat, against the well-traveled forty-year-old lefty Chris Hammond, to keep my springtime momentum going. This was his fifth major-league team in the last five seasons, and his ninth major-league stop overall. Why he pinballed around baseball is a bit of a mystery; in the previous four seasons, pitching for the Braves, Yankees, A’s, and Padres, he posted a 19—6 record including an amazing 0.95 ERA with the Braves in 2002. I knew Chris well, having caught him for the triple-A Buffalo Bisons club in 2001. Not blessed with an overpowering fastball, he featured a devastatingly slow changeup–so slow that even if you were waiting for it, you were likely to be way out in front. And when he did fire his version of a fastball, the contrast in speeds made it hard to catch up to it. You never quite found your balance against him.

Facing Chris, now in a Reds uniform, I pretended that I was playing slow-pitch softball. Sure enough, on the second pitch, his changeup came floating toward me, and I hammered it into the left-center gap for a stand-up double. As Hammond got the ball back from the shortstop, he looked at me with a grin as if to say that he knew I’d been sitting on his changeup. If he’d thrown me three straight eighty-five-mile-per-hour fastballs over the heart of the plate, I would have stared at each one dumbfounded.

By the way, with less than two weeks left in spring training, my batting average now stood at .478.

From the Hardcover edition.

Spring Training 2006

SPRING training did not get off to a promising start. And this was even before I so much as strapped on my shin guards.

I arrived in Clearwater, Florida, in February 2006 with the rest of the pitchers and catchers for my second spring with the Phillies. My only hope to put myself on the club’s radar, as in each of the other four spring camps I’d attended, was to prove that I could catch at the major-league level. Going in, I knew that Philadelphia had its two catchers in Mike Lieberthal and Sal Fasano, and there was nothing I could do to take either one’s spot on the twenty-five-man roster for opening day. The most that a player in my position could hope for was to make enough of a positive impression that if someone went down during the season, I might get called up.

After pulling into the parking lot of the Hampton Inn in our rental car, Marcia, Casey, and I got out and began unpacking the car. I went straight to the trunk for the heavy bags and was dubiously greeted by one of the small Florida birds. I felt something soft and wet hit my head and couldn’t believe what had just happened.

“Mommy!” yelled Casey with exhilarating laughter in her voice. “Did you see that? A birdie just flew by and pooped on Daddy’s head!” My sixyear-old daughter could barely contain her laughter at seeing her big and strong daddy getting pooped on the head by a tiny bird. Marcia didn’t know whether to laugh or not because she was unsure how I would react. I normally have a good sense of humor, but to have a bird poop on your head certainly is not a pleasant experience. Fortunately, seeing the joy and laughter on Casey’s face made me instantly realize that it was funny.

You have got to be kidding me, I thought to myself. My first instinct was that a bird pooping on my head was not a good way to begin spring training.

No sooner had we settled into our hotel room than I received a phone call from Steve Noworyta, the Phillies’ director of minor-league operations. Simply put, he’s like the general manager of the organization’s minor-league teams and oversees all of its minor-league players.

“Hi, Chris,” he said in a concerned tone. “Are you in Clearwater already?”

“Yes.” Why wouldn’t I be? I thought.

“Oh . . .” He sighed an ominous sigh. “Well, I guess we had a bit of a miscommunication. We didn’t want you to show up with the pitchers and catchers, we wanted you to show up next week with the position players. As of right now, it looks like you will play mostly first or third base in triple-A. But since you are already here, I guess you can show up tomorrow and help catch some bullpens and stuff like that.”

To put it mildly, I was pissed off. I had hoped to prove to anyone who would pay attention that I was a good catcher. I knew it, my teammates knew it, and virtually every pitcher who’d ever thrown to me always had great comments regarding my catching ability. By no means was I another Johnny Bench, but they always praised my game calling, my soft hands, my ability to catch the low pitch for a strike, and how I always gave a great target. Over the years, many pitchers had remarked, “Chris, I stare in at your glove, and it’s like I can’t help but throw a perfect strike into it!”

In fact, many of my batterymates had gone to the manager and requested that I catch them in their next start. All catching instructors preach the importance of earning the pitchers’ confidence. “A catcher may be able to hit great, block every ball, and throw every guy out trying to steal, but the only thing that matters is if the pitching staff likes throwing to him,” they’ll stress. “If a pitcher insists that you catch him, that is the best compliment you can receive. And it is that kind of catcher that will not only get to the big leagues but stay there.”

Well, I was that kind of catcher. So why hadn’t I made it?

One reason, I’m pretty sure, was that my ability to play other positions actually undermined my career, in a way. What was my best position? Catcher? First base? Third base? It was always a mystery to them. I always considered myself a catcher who could play elsewhere if needed. However, the decision makers inevitably mistook me for a utility man who could play multiple positions–with catching being just one of them. It seems similar, right? But in the world of professional baseball, there’s a huge difference between the two perceptions. The term utility player tends to refer to guys who play shortstop and second base, maybe third base, too. No team will put its trust in a catcher who is not primarily a catcher.

So to hear that the Phillies had no plans for me to catch during spring training made no sense to me. And they wanted me at first base, of all positions? They had to be kidding. Ryan Howard, the reigning NL Rookie of the Year, played there. All he did in 2005 was hit .288 with 22 homers and 63 RBIs in just half a season.

I hung up the phone in disgust.

“What did you expect?” my wife asked. “Did you really think things were ever going to be easy for you? This is totally par for the course.”

“I really hoped the Phillies would be different,” I replied. “And I’m thirty-three, Marcia. Time is more than running out. If they won’t give me the chance to prove I can catch, I will never make it. Catching is my only hope. They will never call me up as an infielder, especially not at first base.”

No one understood what I had gone through more than Marcia. As many times as I had received great comments from pitchers over the years, oddly enough, she also received the same kind of comments from pitchers’ wives. “Is your husband catching tomorrow?” a wife would ask. “My husband is pitching tomorrow and he loves it when Chris catches.” She heard things like that on a regular basis.

Her response was usually the same as my response to the pitcher. “He loves to catch, but your husband needs to tell that to the manager or the pitching coach–they are the only ones who will listen,” Marcia would say. I had almost taught her word for word what to say when a wife would say these things to her. The typical response from the wife was that her husband had gone into the manager’s office on several occasions and told him that I should be catching.

HERE’S how you know you’re a long shot to crack the opening day roster: When I reported to training camp, I was handed a uniform with a big red 67 on the back. Generally, the higher your number, the lower your status. I also took note that my locker was on the “hopeless” side of the locker room with all the other players destined for the minors. Or oblivion.

I decided to use my frustration as motivation. It may have been only spring training, but I approached every catching drill as though I were preparing for the World Series. Just as important, each and every day I was in Charlie Manuel’s ear, reminding him that catching was my best position. He knew I could hit: In 2002, when he was managing the Indians, I batted .318, 8 HR, 67 RBI for the triple-A Buffalo Bisons and was named team MVP; the previous spring, Charlie’s first as Phillies skipper, I hit at a .313 clip. Now I had to prove to him that I was good defensively. “Just keep your eyes open,” I’d say before morning workouts. “I promise I will surprise you.” He wouldn’t reply, just smile and nod, as if to say, “Okay, go prove it.”

One other factor would make this spring training difficult: It was the first spring that I would be mostly on my own, as Marcia and Casey had to leave the following week. In previous years, they had accompanied me throughout the entire baseball season. But with Casey now in first grade, she could no longer miss so much school. We would all have to try to get used to seeing each other for short stints up until school let out in June.

Through the first weeks of spring training, I knew I was making a bit of a statement. Three days before our first official spring training game, against the New York Yankees, the team’s main catching instructor, Mick Billmeyer, approached me with some positive words. “Coastey,” he said, “after watching you catch bullpens, seeing you in our catching drills, and going by what the pitchers are saying about you, I have been telling Charlie every day that I think you can catch in the big leagues. He also asks about you every day and tells me to keep an eye on you because he wants to know how good of a catcher you really are. He knows you can hit, and he definitely wants to give you a shot at catching in some spring training games. So be ready, you might actually get a chance to impress him.” Mick, a former catcher, seemed empathetic, perhaps because he’d languished in the minors for eight seasons before turning to coaching in the 1990s.

“Also,” he continued, “Carlos Ruiz will be gone for a while to catch for Panama in the World Baseball Classic, so that should also allow you to slip in and catch some innings.” Ruiz had a lock on the starting catcher’s job at Scranton/Wilkes-Barre and figured to put in a lot of time behind the plate during the spring. With him away to participate in the first-ever international baseball tournament, I’d get a few extra innings to show what I could do.

That brief exchange with Mick Billmeyer improved my outlook dramatically. Whether it was a coincidence or not, later that day I really put myself on the map as far as the Phillies were concerned. I got a chance to take live batting practice off Scott Mathieson, a hard-throwing righthander from Vancouver whose fastball had been clocked as high as ninety-nine miles an hour in double-A the previous season. He’d just turned twenty-two and was viewed by many as a can’t-miss prospect. Scott had been tossing bullpen sessions in preparation for the World Baseball Classic, slated to begin the first week of March; I was selected as one of the hitters to face him in his final practice before leaving to join his Canadian teammates. (Several other members of the Phillies would be going to the games, held in the U.S., Japan, and Puerto Rico, including Chase Utley, Philadelphia’s representative on the American team.)

Excited at the opportunity to face live pitching, I was also a little nervous–especially after I glanced behind the batting cage and saw Charlie Manuel standing next to most of the Phillies’ brain trust. There was new general manager Pat Gillick; Ruben Amaro Jr., the assistant GM; and Gillick’s special advisor, Dallas Green, the man who’d managed Philadelphia to its only World Championship, back in 1980. If I was going to open some eyes, this would definitely be an opportune moment to shine. Maybe my only moment.

As I stepped into the batter’s box, catcher Dusty Wathan lifted up his mask and said with a sigh, “Don’t you just hate these live batting practice sessions? Especially against a guy with a fastball like Mathieson’s?”

“Not really,” I said. “I kind of like this stuff.” Most hitters dreaded taking live batting practice off their teammates, for a couple of reasons. One, they don’t like to compete against one of their own, and, two, suddenly the ball is coming in much faster at a time when their reflexes and bat speed aren’t ready for gamelike activity. Me, I’d always enjoyed it, in part because I was good at it. Batting practice is the only time when the pitcher tells the hitter what pitches are coming. Also, there’s really nothing to lose. Either you hit the ball hard, impressing everyone; or you don’t hit the ball hard, and people think you’re not really trying because you don’t like to hit off your team’s own pitchers.

Scott’s first pitch blew by me at around ninety-five miles per hour, according to the radar gun, but high and out of the zone. As it snapped into the catcher’s mitt, I heard Charlie Manuel’s distinctive West Virginia drawl: “How ’bout that Scott Mathieson? He’s throwin’ some heat today. Be careful, Coste!”

I looked back at Charlie, and in my best southern accent, said, “Gotta hit, Charlie,” one of his pet phrases. He’d spent several years as the Cleveland Indians’ hitting coach, and he loves guys who can hit. He’ll walk through the clubhouse, saying to all the hitters, “Gotta hit, son! Gotta hit!”

“All right, then,” he replied, a wide grin on his face. “Go hit him, son! Gotta hit!”

I have always prided myself on being able to hit any fastball. If I know it’s coming, I’ll catch up to it, regardless of its speed. As Mathieson released the next pitch, I gripped the bat tight and let it fly, rocketing the ball at least fifty feet over the fence in left-center field. “How about that Chris Coste!” Charlie exclaimed with a small laugh under his breath. “Be careful out there, Mathieson!”

Next Scott hummed a fastball middle-in, and once again I brought the bat around and sent it over the left-field wall, this time by some seventy-five feet. Dallas Green, once a Phillies pitcher himself, yelled out, “Wow, Charlie, it looks like Coste brought his quick hands with him this year!”

“Well, he did hit twenty bombs last year in Scranton,” the manager responded. I whipped around and looked at Charlie, pleasantly surprised that he knew my stats. The twenty home runs in 2005 was a career high for me. He gave me a quick wink, and I stepped back into the batter’s box. Before I was finished, I’d cracked several more solid hits, including a few that disappeared over the fence. The Grapefruit League games, set to start in a few days, were the real tryouts, of course. Still, I drove back to the Hampton Inn that afternoon satisfied that I’d forced the team’s decision-makers to notice me.

Two days later we held an intrasquad game so that some of the pitchers could get in an inning of work against hitters in a gamelike setting, and the rest of us could get acclimated to game-speed situations. We were all looking forward to the games, which would put an end to days spent practicing the same drills over and over: blocking balls in the dirt, throwing to bases, fielding bunts and pop flies. Five minutes before the intrasquad contest, I stood in the dugout, expecting to watch it from the bench. Gary Varsho, the bench coach, came up to me and asked, “Hey, Coastey, do you have your first baseman’s mitt out here?” On my own time at the end of each day, I’d been taking infield practice with some of the minor-league coaches in camp.

“I’ve got all my gloves, Varsh,” trying to remind him how versatile I was.

“Well, go get it. You’re playing first base.”

“Um... right now?” I assumed he meant that I would fill in at first toward the end of the game.

“Yes, right now!” he answered.

To be honest, I felt a bit startled and unprepared. Ryan Howard was scheduled to play first base. Ordinarily, he would have gotten two or three at-bats, then maybe I or someone else would take over in the sixth or seventh inning. I unloaded a mouthful of sunflower seeds–the ballplayer’s chewing tobacco of the twenty-first century–scrambled to find my hat, and yanked out my dusty old first baseman’s mitt from the bottom of my catcher’s bag. I searched around for some sunglasses, then out to first base I trotted, excited not to be sitting on the bench for three hours like the other minor leaguers from my side of the clubhouse.

My first at-bat, against Phillies ace right-hander Brett Myers, 13—8 the year before, brought a harsh reminder of the difference between facing a hot phenom and an established major-league pitcher. Unfortunately, I was a bit tentative and got around late on a slider, flying out weakly to short right field. While running back to the dugout, I chastised myself for not being my normally aggressive self. The second time up, however, I attacked the ball and doubled off the wall in left-center. Just like that, my confidence surged. Today was going to be a good day; I could feel it.

In the fifth inning, I came up with a runner on second and nobody out. Aaron Myette, another hard-throwing Canadian, stood on the mound. He’d signed with the Phillies after spending the previous season in Japan. Like me, the tall right-hander was fighting to make an impression and full of the same intensity.

I looked down to third-base coach Bill Dancy for the sign. He didn’t flash any–just yelled at the top of his lungs, “Okay, Coastey, do your job!” With a runner on second and no one out, “do your job” meant to hit the ball to the right side or deep to the outfield so I could at least move him to third. This can be a very difficult situation for a right-handed hitter, especially against a pitcher with a good fastball like Myette.

Knowing where I was trying to hit the ball, he threw his best fastball inside for a ball. I looked down at Dusty Wathan and said, “I am really not a big fan of the ‘get the runner over’ situation.” He just looked up at me and smiled.

I dug back into the batter’s box and waited for the next pitch, knowing that another inside fastball was coming. This time the ball wandered over the plate, and I windmilled it. Crack! Off it sailed, high and deep over the wall in left. As I trotted around the bases, a voice from the dugout yelled, “Somebody on that!” a common expression after someone hits a home run in minor-league camp. It means “Retrieve that ball!” During a typical minor-league spring training, players who are not part of the game will be assigned to either home run or foul ball duty. Remember, there aren’t any fans in the stands to toss it back. But since this was major-league spring training, “Somebody on that” was a joke used by minor-league lifers like me to lighten the mood.

Rounding third, I slapped a high-five with Bill Dancy. “Attaway to get the runner over!” he said jokingly.

I whacked another double in my fourth at-bat. So when I stepped up in the ninth inning, my day looked like this: 3-for-4, two doubles, one home run, four runs batted in. I need to finish strong, I thought to myself. On the second pitch I nailed an opposite-field single to right, driving in another run, solidifying me as the unofficial player of the game.

A bevy of Philadelphia reporters, down south for spring training, mobbed me as I entered the clubhouse, making for an odd scene. Ordinarily they would be found on the other side of the room, huddled around the locker of a Phillies star like Howard or Utley, but they were thrilled to have an interesting story emerge so early in camp. My mind raced as I answered their questions.

I wondered if any Japanese scouts had been in the stands. Damn, if they’d seen me, I probably would have been offered a contract for a half million dollars. Well, I consoled myself, at least Charlie Manuel was paying attention, and Pat Gillick, too. I hope Pat was watching.

I came to find out later that day that Ryan Howard had been sickened by food poisoning. Although I certainly would never wish illness or injury on anyone, his absence had opened the door for me, putting me on a path to an eventual unforgettable and amazing spring.

The next day we traveled to nearby Tampa to face the New York Yankees for our first official game. Replacing Howard at first base in the sixth inning, I flied out to right off the sidearming veteran lefty reliever Mike Myers. I got one more chance to make a statement in the top of the eighth, this time with twenty-one-year-old J. B. Cox on the mound. The highly regarded Texan boasted a wicked two-seam fastball that dropped off the table and, like a good two-seamer, induced countless ground balls. I took the first pitch, a two-seamer, for a ball. Normally I would have swung, but I wanted to get a good look at it first. Cox didn’t want to fall further behind in the count, so he laid the next pitch right down the middle of the plate. Big mistake. My first memory after making contact with the ball was almost missing first base as I watched the left fielder run out of room while the ball sailed over his head for a home run. My next memory was thinking that Yankees skipper Joe Torre, one of the winningest managers in baseball history, was watching me, Chris Coste, round the bases. And my childhood hero, Reggie Jackson–Mr. October!–was at Legends Field in his capacity as spring training consultant. Maybe he saw it, too. Then I reminded myself that I needed to be more concerned about making an impression on Charlie Manuel than on Joe Torre.

We went on to win the game 6—3, and as I entered the clubhouse afterward, pitcher Ryan Madson gave me a high five. “That was awesome!” he said. “Keep it up, man, stay hot!”

The next day we faced the Yankees again, only this time at Bright House Networks Field, our home stadium in Clearwater. Once again I took over for Ryan Howard at first base in the sixth inning. With the score tied at ten apiece in the bottom of the ninth, I came to the plate amid a mix of cheers and disappointed jeers. We had two men out and runners on first and second, and it’s safe to say that the remaining Phillies fans in attendance would much rather have seen Ryan Howard come to the plate with the game on the line.

“Hey, Charlie, put Howard back in the game!” yelled an angry fan. “This Cawstee guy has no shot! Besides, we didn’t pay to see guys that have number sixty-seven on their back!” This pissed me off! Not because this fan had no faith in me but because he’d mispronounced my name, calling me “Cawstee” instead of “Coast.” Silent e. Presumably, Ryan Howard has never encountered this problem. But it’s something that has motivated me my entire baseball life. I can remember how embarrassed I felt the first time I heard my name mangled over a loudspeaker when I was fourteen. Back then I promised myself I would become the best baseball player who ever lived so that everyone in the world would know how to pronounce Chris Coste.

On the flip side, I could somewhat understand where the fan was coming from. I had replaced Howard earlier in the game after he had gone 4for-4 with two long home runs and five RBIs. If I were a fan, I too would have had a lot more confidence in Howard than a nobody with 67 on his back. Fortunately, after swinging and missing at the first pitch, I drilled the next pitch into the left-field corner for a game-ending RBI single.

The first person to greet me back in the clubhouse was center fielder Aaron Rowand. “Dude, you are unbelievable!” he exclaimed. “I was telling everyone that the game was over as you walked to the plate. If there was one guy that was guaranteed to get a hit and end the game, it was you!”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Because you are locked in, and other than Howard, you are our hottest hitter.” For a guy like Aaron Rowand to have that much confidence in me was incredibly uplifting. He was the center fielder for the 2005 World Champion Chicago White Sox before coming to Philadelphia in a big winter trade for popular slugger Jim Thome. Maybe the biggest off-season acquisition for the 2006 season, Phillies fans would put a lot of pressure on him.

Once again, I was besieged by reporters at my locker. They knew I had little or no chance of making the team, but they were going to ride this feel-good story as far as it would take them. That day’s headline on the team website read “Coste’s Single Lifts Phils over Yanks.” Quite a compliment considering Ryan Howard’s five-RBI day and Rowand’s first homer in a Phillies uniform. Best of all, the manager was starting to take notice, with Charlie telling the papers, “He’s got it going. You can tell he loves to play baseball.”

Two days later, we faced the National League champion Houston Astros in Clearwater. After I sat on the bench for most of the game, Charlie told me before the ninth inning to be ready to pinch hit in the event we could get a runner into scoring position. I was excited to hear this because it meant he had confidence in me to come up big in a clutch situation. Well, we were down by two runs going into the inning, so clutch is what he was looking for. After scoring a run early in the frame, I came to the plate with two outs and a runner on second base. This is a golden moment, I told myself as I walked to the plate. If I can get a hit here, who knows what could happen. I was having a good spring to that point, and already had one walk-off base hit. Now I had to show everyone, especially Charlie, that it wasn’t just a fluke, that I was indeed a clutch hitter.

Not wasting any time, I stroked the first pitch I saw up the middle to tie the game at three. We went on to win it in the bottom of the tenth, bringing our spring record to 4—0. My average stood at .700. Make that a gaudy .700, as sportswriters are fond of saying.

After the game my new friends from the press paid yet another visit to my locker. We joked about how they’d never spent so much time on the minor-league side of the clubhouse. Then one of them said, “You’ve been having a great spring so far. With David Bell suffering from a bad back and unlikely to be ready for the season opener in April, how do you like your chances of making the team?” Bell was the Phillies’ thirty-threeyear-old starting third baseman. I had no idea that he was out of action. Not that you ever want to see a teammate get hurt, but if he wasn’t going to be ready for the start of the season, my chances of making the team definitely went up, still a long shot, but seemingly rising by the day.

A few days later I was sitting at my locker when Charlie Manuel told me I was finally going to catch against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. Better still, I’d be giving the signs to veteran right-hander Jon Lieber, a seventeen-game winner who carried a lot of clout with the coaches. He approached me right before the game.

“Hey, bro, I was hoping you were going to catch me today. Let’s have a good day.” I’d caught him in a few bullpen sessions earlier in the spring, and he went on to tell me that he liked the way I caught the ball and my big setup. “It feels like I can’t help but throw it to the middle of your mitt,” he said. I actually had to suppress a giggle, because I’d heard that same line, almost word for word, from many other pitchers in the past.

“Well, feel free to tell that to Charlie and Dubee!” I replied. Dubee referred to Rich Dubee, the Phillies’ pitching coach.

“Believe me, I have,” said Lieber. “Several of us have told both of ’em the same thing.”

“That’s awesome. I have fought my whole career to prove I am a catcher, and the pitchers have always said those kinds of things. Unfortunately, nobody has ever listened.”

“Well, Charlie will listen.”

Although Tampa Bay edged us out 4—3, scoring two in the ninth to take the lead, I had a good day. I went 1-for-2 against young fireballing lefty Scott Kazmir, but more important, Lieber threw great and I had a great day catching, even throwing out Ty Wigginton trying to steal second base in the first inning. I would have also thrown out another guy in the third inning, but the umpire, having clearly missed the play, called the runner safe at second.

Charlie Manuel lifted me at the start of the sixth. “Damn, Coastey, you can catch, son!” he exclaimed.

“Damn right! I’ve been telling you that all spring!” I had a big smile on my face, and Charlie flashed me his patented wink.

Still, several days would pass before I received a second opportunity behind the plate, and then only in a minor-league spring training game. Ordinarily, I wouldn’t have been too excited to see action against the Toronto Blue Jays’ triple-A team, except that I’d be handling another one of the Phillies’ top starters, Cory Lidle, who needed to get in some work. He’d posted a 13—11 record in 2005. If I could impress him with my catching ability, I’d open some more eyes among the decision-makers.

Following Lidle’s five shutout innings, the right-hander pulled me aside and had some great comments. “You know, Coastey, I had no idea you were such a good catcher. I really thought of you as an infielder. I am amazed! With the way you hit, how are you not in the big leagues somewhere–at least as a back-up catcher? Not only that, but we were on the same page all day long; I shook you off maybe only twice. You can catch me anytime!” That was the best comment of all. Cory had a repertoire of five pitches, which made it incredibly difficult at times to figure out which one he wanted to throw. I must have developed a psychic ability that day, because he seemed to throw every pitch I called.

“Well, if you are serious, feel free to tell that to Charlie,” I said. “For him to believe in me as a catcher, he has to hear that kind of stuff from his pitchers.”

“Absolutely, I will tell both Charlie and Dubee.”

I knew this was the start of something good. Cory was not the kind of guy to keep his mouth shut; on the contrary, he always spoke his mind. Sometimes, in fact, his candor got him into trouble. The next morning, he called me over to a table in the clubhouse, where he was polishing off his usual breakfast from Chick-fil-A.

“Hey, Coastey, I just talked to both Charlie and Dubee, and I told them exactly what I told you yesterday.”

“How did they take it?”

“They joked about how they’re getting tired of all the pitchers saying the same thing. Apparently they have been hearing the same thing about your catching ability from a lot of the pitchers. It’s not just me and Lieber.”

It had been quite a spring so far. With several of the pitchers wearing out Charlie’s and Dubee’s ears, I knew I would earn more opportunities to impress. And with David Bell’s back still acting up, there was likely to be an open roster spot. I had gone from an anonymous number 67 suiting up on the minor-league side of the clubhouse to a guy with a legitimate shot at making the opening day roster for the Philadelphia Phillies. But the best was yet to come a day later against the Pittsburgh Pirates.

After sitting in the hot sun out in the bullpen for the first six innings, I took over at catcher for Mike Lieberthal in the seventh. Earlier in the day I had come across some bats left behind by a former Phillies outfielder, Jason Michaels, who’d been traded to Cleveland shortly before the start of spring training. Normally I was fanatical about using only my model from Louisville Slugger, but I took Jason’s bats in my hands and just knew they had hits in them. Knew it! They felt great–even looked great, with a dark-flamed finish that gave them a cool and unique look.

Now, like many ballplayers, I can be superstitious. Maybe it’s because we play a sport where failing to get a hit seven times out of ten is good enough to land you in the Hall of Fame, so we figure we can use all the help we can get.

For example, I’ll often smell my bat after I hit a foul ball. Why? I suppose it’s because I used to go to the lake a lot while growing up in Minnesota. And I just love the smell of wood burning, like from a campfire; I associate it with my childhood. Sometimes if you foul off a baseball that’s hurtling toward you at ninety, ninety-five miles per hour, the friction produces that same burnt-wood aroma. Or maybe it’s the smell of the leather. Or both. Anyway, one time early in my career, I just got a piece of a fastball, then held the bat up to my nose. For a moment, there I was, a kid again, back at West McDonald Lake in Minnesota. I proceeded to send the next pitch into the bleachers for a grand slam. Ever since then, I will often sniff my bat, partly out of superstition and partly because I just plain like the smell.

Back to Jason Michaels’s leftover lumber. In the bottom of the seventh inning against the Pirates, I stepped up to the batter’s box with one of his bats. We trailed by four runs and had a runner on first. On a 1—0 count, I sent the next pitch deep over the wall in left center, cutting the deficit to 8—6.

If you’ve ever listened to a Phillies game on the radio, you’re probably familiar with the resonant voice of Harry Kalas, the team’s play-by-play announcer since 1971. From the day I signed with the organization in January, one of my goals was to hear the Hall of Fame broadcaster call one of my home runs. With the crack of the bat, here’s how he called it: “Ooooh, watch that baby... deep to left field... and that ball is outta here! Chris Coste, a two-run home run, and it is now an eight-to-six game as the Phillies come fighting back.”

If the game had ended right there, I would have been thrilled. But in the bottom of the ninth, with our team still trailing by two, I was due up fourth. We had the tying run on first and one out as Ryan Howard, getting a day of rest, was announced as the pinch hitter. The reigning NL Rookie of the Year had already launched seven home runs that spring. Unfortunately, he lofted a high fly ball that just missed going out and tying the game. As soon as the ball parachuted into the outfielder’s glove, the capacity crowd of eight thousand started making its way for the exits.

Wait a minute, I thought to myself. I hit a two-run homer just two innings ago! We still have one out left. How can all these fans leave?

Meanwhile, out in the bullpen, catching instructor Mick Billmeyer and minor-league catcher Dusty Wathan were prognosticating my future. As they told me after the game, Dusty remarked, “Another home run by Coastey would be nice right now.”

“If he hits another homer here, he can almost guarantee himself a spot to go north with the team,” replied Mick.

“Well, if he hits another home run here, not only will he guarantee himself a spot on the team, he can probably pilot the team plane to Philly.”

“Giddyup with that!”

As the count made its way to 3—1, I called time out to gather my thoughts and to clear my eyes. I’d noticed that the wind, which had blown out to center field for most of the game, was now coming in from left field. It would be difficult to pull the ball over the left-field wall against the wind; I’d be better off trying to drive the pitch into the right-field gap. Maybe get a double, which would put the tying run in scoring position. I can also remember telling myself not to chase ball four–after all, I was the tying run and if I could at least get on base it would bring the winning run to the plate. My final thought was how much I despised being the guy who made the last out of the game. In my mind, having to walk off the field as the batter who made the last out was one of the most humiliating situations a ballplayer can be in.

In dramatic fashion, I nailed the ball on a line to deep left field and over the left fielder’s head. To my surprise, it sliced through the wind and cleared the left-field wall by the slimmest of margins, landing safely in the Pirates’ bullpen. Once again, here is how Harry Kalas called the action:

“There’s a long drive, and this game is gonna be tied...I believe ... yes! Into the bullpen! How about Chris Coste! A two-run home run in the ninth inning with two outs. Coste has had two at-bats, two homers, four runs batted in! Amazing!”

As I touched home plate and trotted toward the dugout, I thought happily, There is no way they can keep me off the team now! A barrage of high fives from my teammates greeted me. They all knew the kind of spring I was having and the significance of the situation. If there was any doubt that I was the front runner for David Bell’s open roster spot, they had all been erased after that game.

For the first time in a week, my friends from the Philly media were back around my locker. “I didn’t think you guys were ever going to come back here again,” I joked. After they got their quotes and drifted off, reliever Clay Condrey planted himself in front of me with an angry expression on his face. Like me, he was a journeyman ballplayer; in fact, he’d signed with Philadelphia the same day that I did. Clay was also one of my spring training roommates.

We both broke up laughing. Without his saying a word, I knew what was on his mind: We’d planned to go golfing with our other roommate, pitcher Brian Sanches, later that afternoon; my two home runs sent the game into extra innings, causing us to miss our scheduled tee time.

“I’m so sorry,” I said sarcastically, “I forgot all about our tee time. If I’d remembered, I never would have hit both those home runs today! I would have only hit one and then maybe only a triple in my other at-bat.”

“A triple? You haven’t hit a triple since the Clinton administration,” Clay retorted.

“Okay, maybe a double, and then I would have gotten thrown out trying to stretch it into a triple.”

“That sounds better. Seriously,” he added, “you’d better be careful, because if you keep messing around like this and continue to get all these big hits, you might actually make this team. And guys with number sixty-seven don’t make big-league teams.”

I was still on a high the next day when Charlie Manuel put me in at first base in the eighth inning against the Cincinnati Reds. I’d have just one at-bat, against the well-traveled forty-year-old lefty Chris Hammond, to keep my springtime momentum going. This was his fifth major-league team in the last five seasons, and his ninth major-league stop overall. Why he pinballed around baseball is a bit of a mystery; in the previous four seasons, pitching for the Braves, Yankees, A’s, and Padres, he posted a 19—6 record including an amazing 0.95 ERA with the Braves in 2002. I knew Chris well, having caught him for the triple-A Buffalo Bisons club in 2001. Not blessed with an overpowering fastball, he featured a devastatingly slow changeup–so slow that even if you were waiting for it, you were likely to be way out in front. And when he did fire his version of a fastball, the contrast in speeds made it hard to catch up to it. You never quite found your balance against him.

Facing Chris, now in a Reds uniform, I pretended that I was playing slow-pitch softball. Sure enough, on the second pitch, his changeup came floating toward me, and I hammered it into the left-center gap for a stand-up double. As Hammond got the ball back from the shortstop, he looked at me with a grin as if to say that he knew I’d been sitting on his changeup. If he’d thrown me three straight eighty-five-mile-per-hour fastballs over the heart of the plate, I would have stared at each one dumbfounded.

By the way, with less than two weeks left in spring training, my batting average now stood at .478.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Anyone who has played in the minors can respect what Chris went through to reach his goal. He endured eleven minor league seasons and should be applauded for never giving up. We have all fought through difficulties to achieve our dreams and Chris’s story speaks volumes about determination, drive, and perseverance.”

–Cal Ripken, Jr., baseball’s all-time “Iron Man”

“If baseball gave out awards for fortitude or stubbornness, the biggest trophy would go to catcher Chris Coste. . . . Wives less patient than Marcia Coste may want to hide this book from aging husbands who have dreams of their own.”

–USA Today

“[Coste] has a wide-eyed affection for the game that is contagious.”

–Sports Illustrated

“Remarkable . . . may inspire young readers to follow their dreams.”

–The Boston Globe

“What’s not to love? A hardworking, dedicated man overcomes odds and obstacles to fulfill his dream.”