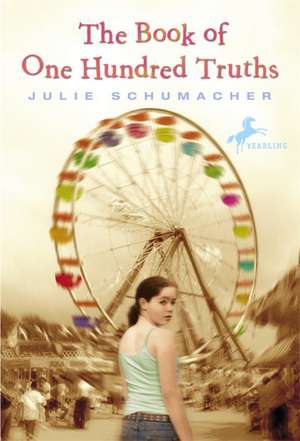

The Book of One Hundred Truths

Autor Julie Schumacheren Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 feb 2008 – vârsta de la 8 până la 12 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Minnesota Book Award (2007)

It's hard for Thea to write four truths a day in the notebook her mother gave her for the summer. Especially when her grandparents' house on the Jersey Shore is even more packed with family than usual, and her cousin Jocelyn wont leave her alone. Jocelyn just might be the world's neatest and nosiest seven-year-old, and she wants to know what's in Thea's notebook. But Thea won't tell anyone about the secret she has promised to keep--or how she lost her best friend (Truth #12), whose name was Gwen.

Now Thea has to babysit in the afternoons, and all Jocelyn wants to do is spy on people. Neither of them expect to see Aunt Ellen and Aunt Celia at the boardwalk in the middle of the day, or for their aunts to lie and insist they were at work. Could it be Thea's not the only one in the family keeping secrets this summer?

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 42.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 64

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.15€ • 8.42$ • 6.78£

8.15€ • 8.42$ • 6.78£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440420859

ISBN-10: 0440420857

Pagini: 182

Dimensiuni: 130 x 191 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

ISBN-10: 0440420857

Pagini: 182

Dimensiuni: 130 x 191 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

Notă biografică

Julie Schumacher is the author of The Book of One Hundred Truths, The Chain Letter, and Grass Angel, a PEN Center USA Literary Award Finalist for Children’s Literature, all published by Delacorte Press. She is also the author of numerous short stories and two books for adults, including The Body Is Water, an Ernest Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award Finalist for First Fiction and an ALA Notable Book of the Year.

Julie Schumacher is the director of the creative writing program and a professor of English at the University of Minnesota. She lives with her husband and their two daughters in St. Paul.

From the Hardcover edition.

Julie Schumacher is the director of the creative writing program and a professor of English at the University of Minnesota. She lives with her husband and their two daughters in St. Paul.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Probably because they didn’t trust me, my parents were grilling me at the airport in Minneapolis, asking all the usual travel questions. Did I have my backpack? Yes. Did I have the claim check for my suitcase? Yes. Did I need to use the bathroom?

“Guess what? They have bathrooms on planes now,” I said.

My father patted his pockets. “Do you need any chewing gum?”

“I already have some.”

“A bottle of water?”

“Dad,” I said. “This is kind of insulting.”

“Okay, I’ll stop. A magazine?”

Every summer since I was six years old, my parents had been sending me to visit my father’s relatives at the beach in New Jersey. They were always more anxious about it than I was. I liked eating lunch on the plane at thirty thousand feet, and I liked staying at my grand- parents’ house, which was full of lumpy, mismatched furniture and old-fashioned wallpaper that would have been seriously ugly anywhere else.

Yes, I said. I had a magazine. I had absolutely everything that a person going on a plane could possibly want.

But then my mother cleared her throat, opened a shopping bag I hadn’t noticed, and offered me a notebook. It was light blue, with thick, heavy unlined paper—a much nicer notebook than the kind I used at school.

“What’s that for?” I felt uneasy. I was already bringing a lot of things with me: a gift for my grandparents, a lunch and some junk food, my CD player and a dozen CDs, and several books that my father insisted I would want to read.

“It’s a notebook of truths,” my mother said. She flipped the pages of the notebook and held it toward me. “You can write anything you want in here, as long as every single thing you write is true.”

“What do you mean, every single thing?” I looked at the notebook but didn’t touch it. On its cover was a white star about the size of my fingertip. All around us, people were pushing strollers and dragging suitcases toward their gates.

“Well, I’m not talking about essays, or even paragraphs,” my mother said. She was standing very close to me; I could smell peppermint on her breath. “I’m only talking about observations. Write a few sentences at first. You can make a list.”

“Gee. A list.” I shifted my backpack to my other shoulder. “That sounds exciting.”

My mother didn’t appreciate sarcasm. “Notebooks are private,” she went on. I was almost exactly her height, and she was looking at me forehead to forehead, eye to eye. “That’s the best thing about them. You can write down any truths at all. Anything you’re thinking.”

“The world is round,” I said. “How’s that for a truth?”

My mother tucked her hair behind her ears and said that the world is round was a fact instead of a truth, and that there was a difference. She said she suspected I knew what it was.

“Time to get on that plane,” my father said. He clapped his hands.

Here was a truth: my father didn’t like goodbyes. He didn’t like train stations or bus depots or airports. I could tell he was nervous by the way he had been jingling the change in his pockets.

A tall blond woman ran over my foot with her rolling suitcase.

“We have one more minute,” my mother said. She straightened the sleeve of my T-shirt and pulled me aside. “You’ll be gone for three weeks. Twenty-two days. If you write down four or five true things every day”—she tapped the cover of the notebook—“you’ll have a hundred. A hundred true things.”

“A hundred,” I repeated. I had to admit that one hundred truths had a certain ring to it.

“You’ll feel better if you use this,” my mother said. “You never know what you might discover. You might learn something new.” Her green eyes were like matching traffic lights. “You might find out something new about who you are.”

I didn’t want to get into that kind of discussion. I took the notebook. It felt good in my hands; the blue cover was soft.

“Off you go, then,” my father said. He gave my ticket to the flight attendant, who wrapped a paper bracelet around my wrist as if I were two years old instead of almost thirteen.

I started down the carpeted hallway and waved. My parents, their arms around each other’s shoulders, waved back.

“We’ll see you soon,” my father said. “Call us when you get there. And have a good time. Behave yourself.”

I told him I would.

But I should probably mention something right now, before this story goes any further: my name is Theodora Grumman, and I am a liar.

From the Hardcover edition.

Probably because they didn’t trust me, my parents were grilling me at the airport in Minneapolis, asking all the usual travel questions. Did I have my backpack? Yes. Did I have the claim check for my suitcase? Yes. Did I need to use the bathroom?

“Guess what? They have bathrooms on planes now,” I said.

My father patted his pockets. “Do you need any chewing gum?”

“I already have some.”

“A bottle of water?”

“Dad,” I said. “This is kind of insulting.”

“Okay, I’ll stop. A magazine?”

Every summer since I was six years old, my parents had been sending me to visit my father’s relatives at the beach in New Jersey. They were always more anxious about it than I was. I liked eating lunch on the plane at thirty thousand feet, and I liked staying at my grand- parents’ house, which was full of lumpy, mismatched furniture and old-fashioned wallpaper that would have been seriously ugly anywhere else.

Yes, I said. I had a magazine. I had absolutely everything that a person going on a plane could possibly want.

But then my mother cleared her throat, opened a shopping bag I hadn’t noticed, and offered me a notebook. It was light blue, with thick, heavy unlined paper—a much nicer notebook than the kind I used at school.

“What’s that for?” I felt uneasy. I was already bringing a lot of things with me: a gift for my grandparents, a lunch and some junk food, my CD player and a dozen CDs, and several books that my father insisted I would want to read.

“It’s a notebook of truths,” my mother said. She flipped the pages of the notebook and held it toward me. “You can write anything you want in here, as long as every single thing you write is true.”

“What do you mean, every single thing?” I looked at the notebook but didn’t touch it. On its cover was a white star about the size of my fingertip. All around us, people were pushing strollers and dragging suitcases toward their gates.

“Well, I’m not talking about essays, or even paragraphs,” my mother said. She was standing very close to me; I could smell peppermint on her breath. “I’m only talking about observations. Write a few sentences at first. You can make a list.”

“Gee. A list.” I shifted my backpack to my other shoulder. “That sounds exciting.”

My mother didn’t appreciate sarcasm. “Notebooks are private,” she went on. I was almost exactly her height, and she was looking at me forehead to forehead, eye to eye. “That’s the best thing about them. You can write down any truths at all. Anything you’re thinking.”

“The world is round,” I said. “How’s that for a truth?”

My mother tucked her hair behind her ears and said that the world is round was a fact instead of a truth, and that there was a difference. She said she suspected I knew what it was.

“Time to get on that plane,” my father said. He clapped his hands.

Here was a truth: my father didn’t like goodbyes. He didn’t like train stations or bus depots or airports. I could tell he was nervous by the way he had been jingling the change in his pockets.

A tall blond woman ran over my foot with her rolling suitcase.

“We have one more minute,” my mother said. She straightened the sleeve of my T-shirt and pulled me aside. “You’ll be gone for three weeks. Twenty-two days. If you write down four or five true things every day”—she tapped the cover of the notebook—“you’ll have a hundred. A hundred true things.”

“A hundred,” I repeated. I had to admit that one hundred truths had a certain ring to it.

“You’ll feel better if you use this,” my mother said. “You never know what you might discover. You might learn something new.” Her green eyes were like matching traffic lights. “You might find out something new about who you are.”

I didn’t want to get into that kind of discussion. I took the notebook. It felt good in my hands; the blue cover was soft.

“Off you go, then,” my father said. He gave my ticket to the flight attendant, who wrapped a paper bracelet around my wrist as if I were two years old instead of almost thirteen.

I started down the carpeted hallway and waved. My parents, their arms around each other’s shoulders, waved back.

“We’ll see you soon,” my father said. “Call us when you get there. And have a good time. Behave yourself.”

I told him I would.

But I should probably mention something right now, before this story goes any further: my name is Theodora Grumman, and I am a liar.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Issues of secrets and lies will resonate with young readers. . . . A compelling novel.”–The Bulletin

“Strong characterizations. . . . Readers will respond to [Jocelyn’s] fortitude.”–Booklist

“Strong characterizations. . . . Readers will respond to [Jocelyn’s] fortitude.”–Booklist

Premii

- Minnesota Book Award Winner, 2007