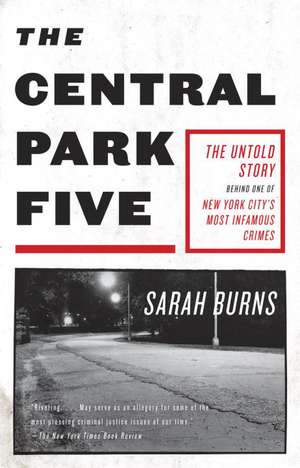

The Central Park Five

Autor Sarah Burnsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 mai 2012

On April 20th, 1989, two passersby discovered the body of the "Central Park jogger" crumpled in a ravine. She'd been raped and severely beaten. Within days five black and Latino teenagers were apprehended, all five confessing to the crime. The staggering torrent of media coverage that ensued, coupled with fierce public outcry, exposed the deep-seated race and class divisions in New York City at the time. The minors were tried and convicted as adults despite no evidence linking them to the victim. Over a decade later, when DNA tests connected serial rapist Matias Reyes to the crime, the government, law enforcement, social institutions and media of New York were exposed as having undermined the individuals they were designed to protect. Here, Sarah Burns recounts this historic case for the first time since the young men's convictions were overturned, telling, at last, the full story of one of New York’s most legendary crimes.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 61.16 lei 3-5 săpt. | +28.51 lei 10-14 zile |

| Hodder & Stoughton – 30 mai 2019 | 61.16 lei 3-5 săpt. | +28.51 lei 10-14 zile |

| Vintage Publishing – 8 mai 2012 | 102.49 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 102.49 lei

Nou

19.61€ • 20.36$ • 16.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 0307387984

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: Illustrations

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Recenzii

“Burns’s gripping tale may serve as an allegory for some of the most pressing criminal justice issues of our time.” ߝThe New York Times Book Review

“This is a controversial and important book, presenting a powerful argument that the minority youths who are convicted of raping and nearly murdering “the Central Park Jogger” were innocent of that crime (though not necessarily of other violent crimes committed in Central Park that night). It demonstrates that our justice system is far from full proof even in the face of alleged confession, eyewitness and forensic evidence. Were these false convictions based on understandable mistakes? Or were they based on racial stereotyping? Read this fine book and make up your own mind.” ߝAlan M. Dershowitz, author of The Trials of Zion

"Burns is a calm, lucid, and concise writer."--NPR

“Gripping from start to finish, The Central Park Five is an unvarnished look at one of the most infamous crimes in New York City history. You may think you know the true story of the Central Park jogger, but you don’t. Sarah Burns tells a harrowing story, in which her only allegiance is to the truth.” ߝKevin Baker, author of Dreamland

“Remarkable…Straightforward, thought-provoking reportage.” ߝBooklist

“A riveting retrospective.” ߝNews Blaze

Notă biografică

Extras

As Raymond sat with his friend in the Taft courtyard that warm afternoon, a bunch of kids who lived there and in the surrounding buildings arrived. One of the boys in the group was Antron McCray, an exceptionally shy fifteen-year-old African-American from Harlem. Antron lived with his mother, Linda, and his stepfather, Bobby McCray, on 111th Street. He had adopted his stepfather's name at an early age and always considered Bobby his real father. The McCrays were devoted to their only son and were involved in his activities. Though he was a tiny five three and weighed only ninety-eight pounds, Antron was a good athlete and played shortstop on a neighborhood baseball team that his stepfather coached. They had gone to Puerto Rico together for an all- star tournament, a highlight of his Little League career. Antron was enrolled in a small public school program called Career Academy, where he enjoyed his social studies classes and got pretty good grades. Antron and Raymond had seen each other before, since they went to different schools housed within the same building, but didn't know each other well.

Over the next hour, the group in the Taft courtyard grew to about fifteen teenagers. Raymond and Antron joined them as they all began to wander south along Madison Avenue, then turned west onto 110th Street, heading toward Central Park. A block ahead, at the corner of the park, was an apartment complex called the Schomburg Plaza. The Schomburg is made up of two narrow thirty-five-story octagonal towers and, behind them, a large, squat, rectangular building. The two towers sit facing the northeast entrance to Central Park on a traffic circle centered at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and 110th Street. They are by far the tallest buildings in the vicinity and dominate, like sentinels, that corner of the park. Built in 1975 as a city development for middle-and low-income families, all three of the unsightly structures are constructed of beige concrete, with deep grooves running vertically like scars up and down the walls.

Yusef Salaam and Korey Wise, both African-Americans, lived in the northwest tower of the Schomburg Plaza complex. Yusef and Korey were good friends but could not have been more different. Yusef was skinny and tall, nearly six three, even at age fifteen. Korey, at sixteen, was only five five, and stockier. Yusef was a talented kid. He had been accepted at LaGuardia High School of Music and Art, a highly selective public school that requires the submission of an art portfolio for admission. Yusef, like Raymond Santana, had been drawing since he was five and was interested in jewelry making and wood sculpture. He also liked to take electronics apart to see how they worked and to try to put them back together. Korey, on the other hand, had had hearing problems from an early age and a learning disability that limited his achievement in school. He was in the ninth grade in April 1989, but his reading skills were nowhere near that level.

Yusef came from a strong family. His mother, a freelance fashion designer and part-time teacher at Parsons School of Design, raised three children on her own, and pushed them to succeed. Yusef was a practicing Muslim and followed the tenets of his religion closely. But he had been kicked out of LaGuardia when a knife was found in his locker. After his expulsion, Yusef switched schools several times; by April of 1989, his mother had placed him at Rice, a private Christian school in Harlem. She had also signed him up for the Big Brothers Big Sisters program, which paired him up with David Nocenti, an assistant U.S. attorney, with whom he'd been spending time for the past four years. Yusef, who was gregarious and laid-back, prided himself on having friends from all over the neighborhood.

Korey Wise was also raised by a single mother, Deloris, who was pregnant in April 1989, and he had three older brothers. Korey was a good friend to Yusef, fiercely loyal, and well liked. At that time, he was dating a girl named Lisa Williams, who lived with a foster family in the same Schomburg tower. But his childhood had been especially difficult. Korey had only recently moved back in with his mother in the Schomburg Plaza; before that, he'd been living in foster care, at a group home in the Bronx. He moved there, he said, because his brothers were "coming and going," and he needed a more stable environment, but Aminah Carroll, a director at the Catholic foster agency that monitored Korey's case, remembered a much more troubled household. Carroll suspected that Korey's hearing problems had resulted from physical abuse, and when she tried to get him treatment, his mother refused to sign the necessary paperwork. A few years earlier, Korey had been on a trip to an amusement park, where he was molested by a group leader.

At sixteen, Korey was a gentle, emotionally stunted boy, his problems amplified by his hearing loss. Carroll remembers his mother as being psychologically as well as physically abusive. Yusef, who knew Korey's family well, remembers Mrs. Wise as an outspoken and strong woman who attended church frequently, but not as someone who was abusive. Whatever the cause, Korey's development was severely delayed and his ability to comprehend his complicated and sometimes dangerous surroundings was woefully inadequate.

That afternoon, Yusef Salaam, Korey Wise, Korey's girlfriend, Lisa, and their friend Eddie were sitting on a bench near the entrance to Central Park. They were watching out for an older boy and his friends, who, they feared, were coming to start a fight. The young man wanted to date Eddie's sister, and Yusef and Korey were prepared to help Eddie fend him off. Korey, true to his loyal personality, had offered to fight the offender on Eddie's behalf. Eddie had taken a metal bar, at least a foot long, from Korey's apartment for protection, and it ended up in the pocket of Yusef's long coat. It was a solid piece of metal wrapped with black tape that was used in the Wise household to brace the apartment door against unwanted intruders.

As they headed back toward the Schomburg towers, Yusef noticed a large group of teenagers approaching along 110th Street from the other direction. He was certain it was the other kid and his gang coming back to fight, until he recognized a friend from his building, Al Morris. The group also included Raymond Santana, Antron McCray, and their friends from the Taft and other nearby housing projects.

Using Yusef's nickname, Al called out to him, "Yo, Kane!" and invited him to come hang out in the park. Yusef saw safety in numbers and joined them. He, in turn, invited Korey, who left Lisa behind and followed Yusef into the park. Still more Schomburg residents joined the crowd that was now headed into Central Park, including a fourteen- year-old African-American named Kevin Richardson.

Kevin lived with his mother, Gracie Cuffee, in the same Schomburg building as Yusef and Korey. Their small apartment was on the thirty- fourth floor of the tower, with a spectacular view of Central Park laid out below from the window. Kevin's parents had split up, but his four older sisters often visited. He was the baby of the family, the boy his mother had always wanted, and the women in his family doted on him and taught him to be polite and thoughtful. Kevin attended Jackie Robinson Junior High School on Madison Avenue at 106th Street, where he played the saxophone and participated in a hip-hop dance troupe called Show Stoppers.

Kevin had started playing football while living in Virginia for a few months when he was twelve, and he had dreams of making the team at Syracuse University. He was quiet and respectful at school and his teachers remembered him as having a good moral compass, though his grades showed that he was having trouble keeping up in class. Kevin looked young for his age, with a round baby face and large features. Kevin recognized Yusef and Korey from the building, but didn't know them well.

As the group, including Kevin Richardson, Korey Wise, Yusef Salaam, Antron McCray, and Raymond Santana, congregated at the northeast entrance to Central Park in the darkening twilight, Raymond counted thirty- three boys.

That same day, Patricia Ellen Meili woke up early, as she always did, so she could be at her office by 7:30 a.m. Trisha, as she was known to her family and friends, often worked long days at the office. She was employed at Salomon Brothers, an investment bank in downtown Manhattan, as a vice president in the Corporate Finance Division. She had been at Salomon since moving to New York after finishing business school at Yale. At five o'clock, Meili decided that she would have to call off her dinner plans because she still had too much to do at the office that evening. She phoned her friend Michael Allen to cancel.

A few hours later, her colleague and former roommate Pat Garrett popped his head over from the adjacent cubicle. He wanted to know about the stereo system Meili had just gotten for her new apartment.

"Why not come over and take a look at it?" she said.

"Sure," he replied.

"Come around ten. That'll give me time to go for a run before you get there." They made a plan to meet at 10:00 p.m. and Meili went home to her apartment on East Eighty-third Street, near York Avenue, where she lived alone. At ten minutes to nine, with the sky already dark, Meili left for her run, wearing black leggings, a long-sleeved white T-shirt over her sports bra, Saucony running shoes, and an AM/FM radio headset. Her keys were in a small Velcro pouch attached to one of her sneakers. She also wore a delicate gold ring in the shape of a bow.

On her way down the stairs from her apartment, she bumped into her neighbor James Lansing, who was on his way back from the gym. They chatted for a few minutes about jogging in the park, and then Meili left the building at five minutes to nine. She headed for Central Park.

The year 1989 had begun with New Yorkers still in shock over the news of a terrorist attack. A bomb smuggled into the luggage hold of Pan Am Flight 103 had detonated as the plane flew over Lockerbie, Scotland, on December 21, 1988. The 747 had been on its way from London Heathrow to New York's JFK Airport, and all 259 people aboard, as well as eleven on the ground, were killed when the plane exploded in midair. It was clear from newspaper articles on January 1, 1989, which included obituaries for some of the victims, that people were still trying to piece together what had happened. Many of the passengers on the flight had been New Yorkers heading home.

The New York they were returning to that winter little resembled the prosperous, vibrant metropolis it had once been. Despite the charms that still made it the place of dreams for many, life in the city had become for others a nightmare that recalled the terrifying, gritty, crime-infested, and corrupt Gotham City of comic books. Over the past decades, New York City had experienced a staggering decline and had reached a low point in its history, with soaring crime rates, which no one had ever seen before or could have imagined just a few decades earlier. It was a place people wished they could leave, and in which today's relative wealth and safety seemed an inconceivable pipe dream.

In Harlem, where Antron, Raymond, Yusef, Kevin, and Korey lived, the streets were filled with thousands of abandoned and burned-out buildings. Bankruptcy for the city had been averted in the seventies, but funding for many services, especially those most valued by residents of poor neighborhoods, had been severely cut or eliminated. Fire stations, libraries, and rehab clinics had been shuttered. After- school programs disappeared and park maintenance faltered. Graffiti covered the subways and buildings throughout Harlem and other parts of the city. Empty lots became repositories for debris and garbage. New Yorkers, especially the poorest among them, mostly African-Americans and Latinos, were desperately in need of services and protection, but the city lacked the resources to fight the increasing challenges that its ghettos faced.

Citywide, muggings were regular events, and no one felt immune. Cars were broken into with startling regularity, often for prizes as minor as a shirt fresh from the dry cleaner's hanging inside the window. Falling asleep on the subway could mean waking up and finding that your pants pockets had been slashed with a box cutter and the contents removed by "lush workers," master pickpockets who preyed especially on drunks. Apartment doors were double-, triple-, and quadruple-bolted, and the "police lock," a piece of steel several feet long that was wedged diagonally between a lock on the inside of the door and a brace on the floor, was a standard protective measure.

Residents had become desensitized to the indignities of city life. When commuters in the Times Square subway station walked down to wait for their train one day, they found a man, stark naked, passed out on the platform. Most simply stepped over him and on to the express train. One woman covered him up with a shopping bag from Saks Fifth Avenue. When a TV producer sitting on the subway realized that a woman near her on the train was relieving herself, the woman could only shrug hopelessly at another passenger across the aisle.

The subways could also be terrifying. One Brooklyn woman was approached on the train by a brazen group of young men who spit into their palms for lubrication before trying to pull the rings from her fingers.

Women especially feared the subways during the winter of 1989, where, among other dangers, a man was on the loose, attacking and dragging women into the endless miles of tunnels beneath the city and then raping, sodomizing, and robbing them. A flyer handed out by the transit police advised women to travel with others and remain close to the token booths while in the stations.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The case of the Central Park Five is being revisited with a new acclaimed Netflix limited series on the subject, When They See Us, directed by Ava DuVernay. This is the only book that is going to tell you all you need to know about one of the most infamous criminal cases in American history. A trial that, thirty years on, still bears a striking, and unsettling, resemblance to our current political climate in the era of President Donald Trump.

In April 1989, a white woman who came to be known as the 'Central Park jogger' was brutally raped and severely beaten, her body left crumpled in a ravine. Amid the staggering torrent of media coverage and public outcry that ensued, exposing the deep-seated race and class divisions in New York City at the time, five teenagers were quickly apprehended - four black and one Hispanic. All five confessed, were tried and convicted as adults despite no evidence linking them to the victim.

Over a decade later, when DNA tests connected serial rapist Matias Reyes to the crime, the government, law enforcement, social institutions and media of New York were exposed as having undermined the individuals they were designed to protect. In The Central Park Five, Sarah Burns, who has worked closely with the young men to uncover and document the truth, recounts the ins and outs of this historic case for the first time since their convictions were overturned, telling, at last, the full story of one of America's most legendary miscarriages of justice.