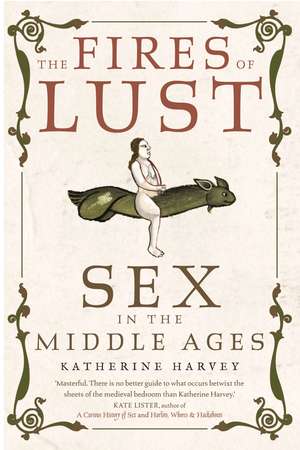

The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages

Autor Katherine Harveyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 2 dec 2022

The medieval humoral system of medicine suggested that it was possible to die from having too much—or too little—sex, while the Roman Catholic Church taught that virginity was the ideal state. Holy men and women committed themselves to lifelong abstinence in the name of religion. Everyone was forced to conform to restrictive rules about who they could have sex with, in what way, how often, and even when, and could be harshly punished for getting it wrong. Other experiences are more familiar. Like us, medieval people faced challenges in finding a suitable partner or trying to get pregnant (or trying not to). They also struggled with many of the same social issues, such as whether prostitution should be legalized. Above all, they shared our fondness for dirty jokes and erotic images. By exploring their sex lives, the book brings ordinary medieval people to life and reveals details of their most personal thoughts and experiences. Ultimately, it provides us with an important and intimate connection to the past.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 84.47 lei 3-5 săpt. | +18.69 lei 5-11 zile |

| REAKTION BOOKS – 2 dec 2022 | 84.47 lei 3-5 săpt. | +18.69 lei 5-11 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 129.52 lei 3-5 săpt. | +26.88 lei 5-11 zile |

| REAKTION BOOKS – 25 noi 2021 | 129.52 lei 3-5 săpt. | +26.88 lei 5-11 zile |

Preț: 84.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.16€ • 16.92$ • 13.45£

16.16€ • 16.92$ • 13.45£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Livrare express 22-28 februarie pentru 28.68 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781789146561

ISBN-10: 1789146569

Pagini: 296

Ilustrații: 17 halftones

Dimensiuni: 159 x 235 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: REAKTION BOOKS

Colecția Reaktion Books

ISBN-10: 1789146569

Pagini: 296

Ilustrații: 17 halftones

Dimensiuni: 159 x 235 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: REAKTION BOOKS

Colecția Reaktion Books

Notă biografică

Katherine Harvey is an honorary research fellow at Birkbeck, University of London. She holds a PhD in medieval history from King’s College London and has published widely on the Middle Ages.

Extras

Since virginity has always been particularly valued as a feminine virtue, it is unsurprising that it was particularly associated with female saints, to the extent that some historians have argued that it was almost impossible for a non-virginal woman to be considered truly holy. The most obvious embodiment of this ideal was the Virgin Mary, to whom many medieval Christians of both sexes were passionately devoted. It was widely believed that she remained a virgin after the conception and birth of Christ, and indeed for her entire life; some even suggested that she had been impregnated by a ray of pure light, possibly through the ear. There was a strong desire to separate the Virgin from not only the indignities of sexual intercourse, but the related contaminations of the female body, so that it was widely believed that the birth of Christ was free from pain and from the polluting effects of afterbirth. Some authorities suggested that, thanks to her Immaculate Conception, Mary would not have menstruated.

Although Mary was pre-eminent among the medieval virgin-saints, she had numerous popular counterparts, notably the Virgin Martyrs. These Roman girls were the heroines of highly formulaic tales in which they converted to Christianity against the wishes of their pagan families and died in defence of their faith and their virginity, often after undergoing extreme physical and mental trials. One of the best known was St Agnes, a thirteen-year-old girl who faced torments including imprisonment in a brothel and a miraculously unsuccessful burning before she was eventually stabbed to death. Moreover, such powerfully disturbing stories were not confined to the history books. When Oda of Hainault’s (d. 1158) parents arranged a marriage for her, she insisted that she intended to preserve her virginity for her heavenly spouse and cut off her nose with a sword. Although Oda lived as a nun for many years after this incident, her hagiographer presented her as a martyr for virginity.

The medieval Church also placed considerable value on male virginity, a virtue embodied by Christ. The Golden Legend notes that John the Baptist was also a lifelong virgin, while St George was ‘like sand . . . dry of the lusts of the flesh’, and John the Evangelist abandoned his wedding feast at Cana to follow Jesus and live a life of perpetual virginity. Again, such figures were not restricted to the distant past. In the eleventh century, the virgin king emerged as a significant figure; Edward the Confessor, the English king whose death without issue in 1066 led to the Norman Conquest, is probably the best known. Many bishops were similarly celebrated for their sexual purity: St Wulfstan of Worcester (1062–95), for example, was ‘so exceptionally chaste that when his life was ended, he displayed in heaven the sign of his virginity which was still intact’.

Despite its high ideals and strong rhetoric, medieval Christianity was ultimately a religion that offered hope and the possibility of forgiveness. The Virgin Mary seemed to have a particular weakness for sexual sinners, and collections of her miracles often include stories of fornicators who were saved by her intervention; the Castilian priest Gonzalo de Berceo (c. 1197–c. 1264) included three examples in his Miracles of Our Lady. The first concerned a sexton who left his abbey at night, in search of sexual adventures. As he returned, he fell into a river and drowned. Devils tried to carry off his soul, but the Queen of Heaven came to his rescue and the monk was restored to life. Henceforth, he was a changed man – although he remained devoted to Mary. She also saved a Cluniac monk who had sex with his mistress before going on pilgrimage, and an abbess who found herself pregnant after a single lapse. This woman’s sin was nearly uncovered, but Mary intervened by spiriting her baby away to be raised by a hermit and eradicating all physical signs of her ordeal.

What all of these individuals had in common, besides their sexual transgressions, was a genuine contrition for their sins. Perhaps the ultimate embodiment of such penitence was Mary Magdalene, whose cult exploded in popularity around 1200. The medieval Magdalene was a composite of several biblical Marys and bore little resemblance to the woman depicted in the Gospels. According to The Golden Legend, she was ‘a woman who gave her body to pleasure’, until she met Jesus. He forgave her sins, and she became one of His most devoted followers. She received many ‘marks of love’ from Christ, who resurrected her brother and allowed her to do the housekeeping on His travels. If Mary Magdalene’s sexual sins did not bar her from Christ’s inner circle, they also offered medieval Christians hope that they too might be redeemed. Consequently, they celebrated her enthusiastically: her feast was one of the most important in the Christian calendar, professions and institutions adopted her as their patron saint, and everything from Oxbridge colleges to daughters were named after her. As Humbert of Romans, the head of the Dominican order, preached in the mid-thirteenth century: ‘no other woman in the world was shown greater reverence, or believed to have greater glory in Heaven.’

Although Mary was pre-eminent among the medieval virgin-saints, she had numerous popular counterparts, notably the Virgin Martyrs. These Roman girls were the heroines of highly formulaic tales in which they converted to Christianity against the wishes of their pagan families and died in defence of their faith and their virginity, often after undergoing extreme physical and mental trials. One of the best known was St Agnes, a thirteen-year-old girl who faced torments including imprisonment in a brothel and a miraculously unsuccessful burning before she was eventually stabbed to death. Moreover, such powerfully disturbing stories were not confined to the history books. When Oda of Hainault’s (d. 1158) parents arranged a marriage for her, she insisted that she intended to preserve her virginity for her heavenly spouse and cut off her nose with a sword. Although Oda lived as a nun for many years after this incident, her hagiographer presented her as a martyr for virginity.

The medieval Church also placed considerable value on male virginity, a virtue embodied by Christ. The Golden Legend notes that John the Baptist was also a lifelong virgin, while St George was ‘like sand . . . dry of the lusts of the flesh’, and John the Evangelist abandoned his wedding feast at Cana to follow Jesus and live a life of perpetual virginity. Again, such figures were not restricted to the distant past. In the eleventh century, the virgin king emerged as a significant figure; Edward the Confessor, the English king whose death without issue in 1066 led to the Norman Conquest, is probably the best known. Many bishops were similarly celebrated for their sexual purity: St Wulfstan of Worcester (1062–95), for example, was ‘so exceptionally chaste that when his life was ended, he displayed in heaven the sign of his virginity which was still intact’.

Despite its high ideals and strong rhetoric, medieval Christianity was ultimately a religion that offered hope and the possibility of forgiveness. The Virgin Mary seemed to have a particular weakness for sexual sinners, and collections of her miracles often include stories of fornicators who were saved by her intervention; the Castilian priest Gonzalo de Berceo (c. 1197–c. 1264) included three examples in his Miracles of Our Lady. The first concerned a sexton who left his abbey at night, in search of sexual adventures. As he returned, he fell into a river and drowned. Devils tried to carry off his soul, but the Queen of Heaven came to his rescue and the monk was restored to life. Henceforth, he was a changed man – although he remained devoted to Mary. She also saved a Cluniac monk who had sex with his mistress before going on pilgrimage, and an abbess who found herself pregnant after a single lapse. This woman’s sin was nearly uncovered, but Mary intervened by spiriting her baby away to be raised by a hermit and eradicating all physical signs of her ordeal.

What all of these individuals had in common, besides their sexual transgressions, was a genuine contrition for their sins. Perhaps the ultimate embodiment of such penitence was Mary Magdalene, whose cult exploded in popularity around 1200. The medieval Magdalene was a composite of several biblical Marys and bore little resemblance to the woman depicted in the Gospels. According to The Golden Legend, she was ‘a woman who gave her body to pleasure’, until she met Jesus. He forgave her sins, and she became one of His most devoted followers. She received many ‘marks of love’ from Christ, who resurrected her brother and allowed her to do the housekeeping on His travels. If Mary Magdalene’s sexual sins did not bar her from Christ’s inner circle, they also offered medieval Christians hope that they too might be redeemed. Consequently, they celebrated her enthusiastically: her feast was one of the most important in the Christian calendar, professions and institutions adopted her as their patron saint, and everything from Oxbridge colleges to daughters were named after her. As Humbert of Romans, the head of the Dominican order, preached in the mid-thirteenth century: ‘no other woman in the world was shown greater reverence, or believed to have greater glory in Heaven.’

Recenzii

"When does sex become rumpy-pumpy? . . . By the Middle Ages sex is indisputably odd. Reading Harvey’s The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages, I found myself thinking: weird, weirder, and, occasionally, whoa! This is an eye-watering, jaw-dropping, blush-raising book. Harvey, a medieval historian and honorary research fellow at Birkbeck, has peeped through the keyhole of the past and caught the Middle Ages in flagrante. The tone is spot-on: curious but not prurient; correct yet amused."

"The story of Simon the goat-lover is just one of hundreds of weird and wonderful anecdotes that rub together in Harvey’s jaunty study of late-medieval sex. . . . Her book is an enjoyable romp, smart as well as funny. It left me fully satisfied, with a big smile on my face."

"An expansive, accessible and highly engaging account of what we do—and don't—know about western European sexual culture in the Middle Ages. The book offers multiple insights into the realities of medieval sex."

"This lively, engaging study combines a scholarly rigor with a sharp eye for telling detail, told in a fluid style that keeps the pages turning. A culture in which clerics commissioned sheelagh-na-gigs—graphic carvings of women displaying their genitals—to adorn their holy buildings perplexes us. Harvey takes great care to explain this complicated culture."

"[An] irresistibly eccentric cultural history. . . . Impeccably researched and impossibly entertaining, The Fires of Lust is a work that transcends its scholarly purpose."

"Harvey takes the reader on a memorable, occasionally eye-watering, journey beneath the medieval bedsheets, from swallowing a bee as contraceptive to applying quicklime to the penis to cure STDs. It's an enjoyable romp."

"When it came to copulation, spinning a good yarn was preferred. Harvey’s The Fires of Lust is part of that venerable tradition. She has written an entertaining but thoughtful study, descriptive without becoming didactic or pedantic. Her message is, depending on your perspective, reassuring: 'then' is not all that different from 'now'—when it comes to sex, la plus ca change, la plus la meme chose."

"I can’t think of more brilliant Christmas book to give to one’s significant other if they have even a passing interest in medieval Europe or the rich and extraordinary sex life of its inhabitants."

“In her provocatively titled book, The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages, Harvey sets out to challenge stereotypes and explode myths about sex and sexuality in the Middle Ages. She does this admirably, conveying the richness, complexity, and diversity of medieval ideas and medieval people’s sexual behaviors. . . . Harvey utilizes a wide body of legal, theological, and medical sources contextualized by a prodigious array of case studies that bring medieval people to life and demonstrate how theory worked (or did not) in practice. . . . Harvey has provided an excellent introduction into the beliefs and the lived experience of sex in the Middle Ages. Her book is rigorous, empathetic, and deeply engaging. Fires of Lust is an excellent overview, especially for non-specialists, students, and general interest readers."

"A lively and readable account rooted in a deep knowledge of the scholarly literature on sexuality in medieval western Europe. Harvey’s specialism in the history of medicine provides particular depth, and is integrated with legal and cultural material to create a sparkling and convincing whole."

“Masterful. There is no better guide to what occurs betwixt the sheets of the medieval bedroom than Harvey. The Fires of Lust—an absolute triumph.”

“With unabashed directness, a delicate touch of wit, and constant humanity, Harvey surveys the world of medieval sex and sexuality. Throughout The Fires of Lust she situates the twin themes of morality and medicine in the social and material world that medieval people inhabited. What those people thought, felt, feared, and hoped for all play a part, alongside the pronouncements of theologians, lawmakers, and intellectuals. Here, in its messy complexity, is medieval life—life laid bare, but always with respect and care. A triumph.”

"Learned, fun, and full of surprises—a fascinating, wide-ranging guide to medieval sexual attitudes and experiences."