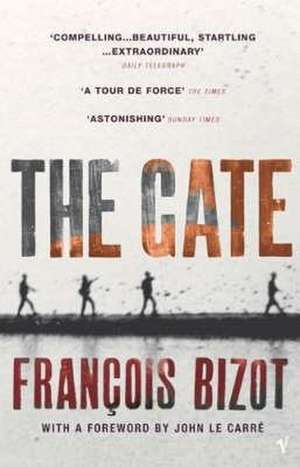

The Gate

Autor Francois Bizoten Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 feb 2004

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 58.16 lei 24-35 zile | +20.45 lei 4-10 zile |

| Vintage Publishing – 5 feb 2004 | 58.16 lei 24-35 zile | +20.45 lei 4-10 zile |

| Vintage Publishing – 31 dec 2003 | 101.69 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 58.16 lei

Preț vechi: 69.59 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 87

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.13€ • 11.60$ • 9.25£

11.13€ • 11.60$ • 9.25£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 ianuarie-04 februarie 25

Livrare express 04-10 ianuarie 25 pentru 30.44 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780099449195

ISBN-10: 0099449196

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: maps

Dimensiuni: 129 x 200 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0099449196

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: maps

Dimensiuni: 129 x 200 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Francois Bizot is an ethnologist who has spent the greater part of his career studying Buddhism. He is the Director of Studies at Ecole Pratique des Hautes-etudes and holds the chair in Southeast Asian Buddhism at the Sorbonne. He lives in Paris.

Extras

Chapter One

FROM AMONG MY MEMORIES there comes up today the image of a gate. It appears before me and I recognize the pathetic hinge which was both a beginning and an end in my life. It is made of two swinging panels, which haunt my dreams, and wire mesh welded onto a tubular frame. It closed off the main entrance to the French Embassy when the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh in April 1975.

I saw it again thirteen years later, when I first returned to Cambodia. That was in 1988, at the onset of the rainy season. This gate seemed much smaller and flimsier. I let my eyes and my hands wander blindly over it, immediately startled by my own temerity, not at all sure what I was looking for and not suspecting what I would find. A lock, slightly askew; evidence of welding; reinforcement plates at each corner: all these scars suddenly seemed to me vitally important. My eyes had always looked past them, never at them. An unexpected blend of confusion and fear overcame me. As the gate became real, and took on an existence of its own, it gave me a sense of pleasure, at the same time as horror welled up inside me.

This was not just the pleasure of releasing tears. It was a new reality, overlaying my memories, which made me think of the workmen who had indifferently welded the metal grille to the framework, and the builders who had pushed the hinges into the cement. Could they ever have imagined that this assemblage would one day be the instrument of such dramatic events? I couldn’t understand why an embassy should have such a shoddy gate, or how such fragile mesh could have resisted so many strong hopes or opened itself to so many heavy wrongs. I remembered a far more imposing structure, heavy and impassable, built to restrain and repulse. I saw—almost with embarrassment—the wrought ironwork suddenly exposed before me: its substance, its lesions, its points of distress, struck me as laughable.

An unexpected sweetness came into me at the same time as the horror welled up again—a fusion that will forever flow in my veins. It made me totter, but did not dispel my stifling unease. I was overwhelmed by the mockery of time, by the shallow nature of things.

The same feelings affected me inside the former embassy, in the chancellery. Both floors of the building had been taken over by an orphanage for girls. The warden was sitting in the corner of an empty room on the ground floor. He accompanied me to our former offices, now converted into bedrooms. Little girls, as if from some abyss, were there, silent, sitting on mats on the floor. Some of them were doing their hair. They had been born shortly before or after 1975; their parents had been massacred when the Khmer Rouge had seized power. The image of their tranquil faces still moves me deeply. I was immediately over- come by suppressed sobbing and ridiculous bubbles formed at the corners of my mouth. Was it the undisguised hardship, the peaceful masks of these young people who had been spared; or these empty walls, with no doors or shutters—which had framed hours of fear, where my distress had taken refuge, from April 17 to May 8, 1975—that caused me such bodily pain?

My whole Cambodian past was just waking in me, and now it ran up against an image of a present with no memory. Until then, it had been no more than signs; now the drama of the Khmer country was suddenly and bluntly revealed to me, in this very inconsistency. A drama “without importance,”* as it were, uncere-

*William Shawcross, Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia.

moniously pinned up in my imagination; all its tangible traces melting away as things evolved, sealed off beneath the marks left behind, movingly distorted on the surface of time.

Crossing the courtyard to leave the embassy, I examined the asphalt: unchanged, with its old pattern of cracks, and yet, to my eyes, it seemed to be coated with the deposit of events. I looked for places where I had set foot twenty years earlier, and my gaze fell on the very spot where Ung Bun Hor, the last president of the National Assembly, had stood, legs trembling, stubbornly and mechanically undoing his trousers. The two French gendarmes who accompanied him and lent support—for the poor man had collapsed at the sight of the Khmer Rouge soldiers waiting for him on the other side of the gate—had hesitated for a long time before realizing that he was losing his mind. A jeep and two covered trucks were parked outside. Princess Manivane, Prince Sihanouk’s third wife, had already climbed into the back of one of the vehicles, accompanied by her daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren, who had merrily come out of their hiding place. .

. .

I will come back to these moments later on. What is more urgent is to pin down where my thoughts lie; they leap about, pressed upon from all sides. To do this I must think back to the beginning. Back to my father’s death, which my thoughts still dwell on. Because the void it carved out left me so alone and so destitute that I had to rebuild my way of thinking, using only basic elements, like a nomad who will not load himself down with anything superfluous. The day my father died, I realized that he had taken with him the masks of protection that I used to put on. To live, to overcome my suffering, I was going to have to erase the slate of the past, just as the revolutionary does, and choose, one by one, whatever gestures promised to be the most immediately effective. It was such a fundamental maneuver that even today—and ever since the day of his death—nothing can be decided, and nothing concluded, without referral to this new point of origin.

At the same time, even though my father’s passing left an inextinguishable rage in me, it reminds me of a love which I often find happiness in thinking about.

The loss of Cambodia, on the other hand, of the villages hidden among foliage, of the copse-lined paddy fields scattered with tufts of borassus palms, only makes me feel despondent. I spoke so much about this to the same friends during the shameful years after 1975—remember them—when the “peasants’ liberation” shone in the West with the fire of revolution; the words were expelled from my mouth by the ignominy I felt, yet gradually the life force ran out of them. As it is for words, so it is, oddly, for the touches and precise strokes of love: one dares not give the same caress to a woman too often. And so, for years now, I no longer speak about my father or about Cambodia, in order to preserve—as a foundered junk is preserved in peat—the life of the monsters I carry, moving in me, even if deep inside, their hellish call fuels the memory.

So the gate does not open onto the agonized cries of the tortured in Tuol Sleng prison but onto absurdity and despair. It is not the events themselves, the brutal facts or their dates that matter. What matters is the weight of the life that gave rise to them, reappearing suddenly out of the silence of things, in the everyday object where those who have borne the events on their flesh can read, thirty years later, the traces of a destiny. This soldier, lying there beneath the stone, is the son or the uncle of someone you know, the lover of the woman you came across, blown to pieces by the side of the road, wearing the new sarong she so carefully chose at the market this morning. Is this not the only reality, this emotion, this link with life and with beings, shut up inside things?

The south panel of the gate is preserved at the far end of the grounds of the French Embassy, which has been rebuilt on the same spot, like a little altar erected to the spirits of the dead. The several million dead. If you hold your breath, you can still hear the heavy footsteps of the exiles as they make their way along the old boulevard with their bundles. The rust that has eaten into the panel has not, in my eyes, affected its radiance. With time, it has taken on a surprising beauty. Like anything beautiful, or accomplished, or enduring—anything finally worthwhile—it has become simple, and the mesh has become regular: like a line in a Matisse drawing. It expresses, in an instant, so many things about the roots of life that you feel all at once like crying, and dying, and living.

I wrote the lines that follow in discomfort, bent forward, with my forehead pressed against that mesh. The Khmer Rouge, some time after 1975, or perhaps the orphan girls who took over the premises in 1980, have treated it to a coat of green cellulose paint; now it is chipped, but beneath it you can, here and there, make out the original gray.

FROM AMONG MY MEMORIES there comes up today the image of a gate. It appears before me and I recognize the pathetic hinge which was both a beginning and an end in my life. It is made of two swinging panels, which haunt my dreams, and wire mesh welded onto a tubular frame. It closed off the main entrance to the French Embassy when the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh in April 1975.

I saw it again thirteen years later, when I first returned to Cambodia. That was in 1988, at the onset of the rainy season. This gate seemed much smaller and flimsier. I let my eyes and my hands wander blindly over it, immediately startled by my own temerity, not at all sure what I was looking for and not suspecting what I would find. A lock, slightly askew; evidence of welding; reinforcement plates at each corner: all these scars suddenly seemed to me vitally important. My eyes had always looked past them, never at them. An unexpected blend of confusion and fear overcame me. As the gate became real, and took on an existence of its own, it gave me a sense of pleasure, at the same time as horror welled up inside me.

This was not just the pleasure of releasing tears. It was a new reality, overlaying my memories, which made me think of the workmen who had indifferently welded the metal grille to the framework, and the builders who had pushed the hinges into the cement. Could they ever have imagined that this assemblage would one day be the instrument of such dramatic events? I couldn’t understand why an embassy should have such a shoddy gate, or how such fragile mesh could have resisted so many strong hopes or opened itself to so many heavy wrongs. I remembered a far more imposing structure, heavy and impassable, built to restrain and repulse. I saw—almost with embarrassment—the wrought ironwork suddenly exposed before me: its substance, its lesions, its points of distress, struck me as laughable.

An unexpected sweetness came into me at the same time as the horror welled up again—a fusion that will forever flow in my veins. It made me totter, but did not dispel my stifling unease. I was overwhelmed by the mockery of time, by the shallow nature of things.

The same feelings affected me inside the former embassy, in the chancellery. Both floors of the building had been taken over by an orphanage for girls. The warden was sitting in the corner of an empty room on the ground floor. He accompanied me to our former offices, now converted into bedrooms. Little girls, as if from some abyss, were there, silent, sitting on mats on the floor. Some of them were doing their hair. They had been born shortly before or after 1975; their parents had been massacred when the Khmer Rouge had seized power. The image of their tranquil faces still moves me deeply. I was immediately over- come by suppressed sobbing and ridiculous bubbles formed at the corners of my mouth. Was it the undisguised hardship, the peaceful masks of these young people who had been spared; or these empty walls, with no doors or shutters—which had framed hours of fear, where my distress had taken refuge, from April 17 to May 8, 1975—that caused me such bodily pain?

My whole Cambodian past was just waking in me, and now it ran up against an image of a present with no memory. Until then, it had been no more than signs; now the drama of the Khmer country was suddenly and bluntly revealed to me, in this very inconsistency. A drama “without importance,”* as it were, uncere-

*William Shawcross, Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia.

moniously pinned up in my imagination; all its tangible traces melting away as things evolved, sealed off beneath the marks left behind, movingly distorted on the surface of time.

Crossing the courtyard to leave the embassy, I examined the asphalt: unchanged, with its old pattern of cracks, and yet, to my eyes, it seemed to be coated with the deposit of events. I looked for places where I had set foot twenty years earlier, and my gaze fell on the very spot where Ung Bun Hor, the last president of the National Assembly, had stood, legs trembling, stubbornly and mechanically undoing his trousers. The two French gendarmes who accompanied him and lent support—for the poor man had collapsed at the sight of the Khmer Rouge soldiers waiting for him on the other side of the gate—had hesitated for a long time before realizing that he was losing his mind. A jeep and two covered trucks were parked outside. Princess Manivane, Prince Sihanouk’s third wife, had already climbed into the back of one of the vehicles, accompanied by her daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren, who had merrily come out of their hiding place. .

. .

I will come back to these moments later on. What is more urgent is to pin down where my thoughts lie; they leap about, pressed upon from all sides. To do this I must think back to the beginning. Back to my father’s death, which my thoughts still dwell on. Because the void it carved out left me so alone and so destitute that I had to rebuild my way of thinking, using only basic elements, like a nomad who will not load himself down with anything superfluous. The day my father died, I realized that he had taken with him the masks of protection that I used to put on. To live, to overcome my suffering, I was going to have to erase the slate of the past, just as the revolutionary does, and choose, one by one, whatever gestures promised to be the most immediately effective. It was such a fundamental maneuver that even today—and ever since the day of his death—nothing can be decided, and nothing concluded, without referral to this new point of origin.

At the same time, even though my father’s passing left an inextinguishable rage in me, it reminds me of a love which I often find happiness in thinking about.

The loss of Cambodia, on the other hand, of the villages hidden among foliage, of the copse-lined paddy fields scattered with tufts of borassus palms, only makes me feel despondent. I spoke so much about this to the same friends during the shameful years after 1975—remember them—when the “peasants’ liberation” shone in the West with the fire of revolution; the words were expelled from my mouth by the ignominy I felt, yet gradually the life force ran out of them. As it is for words, so it is, oddly, for the touches and precise strokes of love: one dares not give the same caress to a woman too often. And so, for years now, I no longer speak about my father or about Cambodia, in order to preserve—as a foundered junk is preserved in peat—the life of the monsters I carry, moving in me, even if deep inside, their hellish call fuels the memory.

So the gate does not open onto the agonized cries of the tortured in Tuol Sleng prison but onto absurdity and despair. It is not the events themselves, the brutal facts or their dates that matter. What matters is the weight of the life that gave rise to them, reappearing suddenly out of the silence of things, in the everyday object where those who have borne the events on their flesh can read, thirty years later, the traces of a destiny. This soldier, lying there beneath the stone, is the son or the uncle of someone you know, the lover of the woman you came across, blown to pieces by the side of the road, wearing the new sarong she so carefully chose at the market this morning. Is this not the only reality, this emotion, this link with life and with beings, shut up inside things?

The south panel of the gate is preserved at the far end of the grounds of the French Embassy, which has been rebuilt on the same spot, like a little altar erected to the spirits of the dead. The several million dead. If you hold your breath, you can still hear the heavy footsteps of the exiles as they make their way along the old boulevard with their bundles. The rust that has eaten into the panel has not, in my eyes, affected its radiance. With time, it has taken on a surprising beauty. Like anything beautiful, or accomplished, or enduring—anything finally worthwhile—it has become simple, and the mesh has become regular: like a line in a Matisse drawing. It expresses, in an instant, so many things about the roots of life that you feel all at once like crying, and dying, and living.

I wrote the lines that follow in discomfort, bent forward, with my forehead pressed against that mesh. The Khmer Rouge, some time after 1975, or perhaps the orphan girls who took over the premises in 1980, have treated it to a coat of green cellulose paint; now it is chipped, but beneath it you can, here and there, make out the original gray.

Recenzii

“A harrowing narrative, worthy of a novel by Graham Greene or John le Carré… [It] possesses the indelible power of a survivor’s testimony.” --The New York Times

“It possesses such truth of feeling, such clarity and conviction of narrative, such a wealth of image and adventure, and such depths of long-held passion that I do believe it is indeed that rarest thing: a classic.” – John le Carré , from the Foreword

“A deeply unsettling account of a particular ordeal that suggests larger questions: the moralities of power's ends and means, the character of revolutionary fanaticism and the indecipherable humanity that flickers within it. . . . by turns evocative, wise and crisscrossed by fury.” – The New York Times Book Review

“[A] fascinating book, to say the least. Passages of The Gate are riveting, some scenes heartbreaking.” –The Wall Street Journal

“It possesses such truth of feeling, such clarity and conviction of narrative, such a wealth of image and adventure, and such depths of long-held passion that I do believe it is indeed that rarest thing: a classic.” – John le Carré , from the Foreword

“A deeply unsettling account of a particular ordeal that suggests larger questions: the moralities of power's ends and means, the character of revolutionary fanaticism and the indecipherable humanity that flickers within it. . . . by turns evocative, wise and crisscrossed by fury.” – The New York Times Book Review

“[A] fascinating book, to say the least. Passages of The Gate are riveting, some scenes heartbreaking.” –The Wall Street Journal