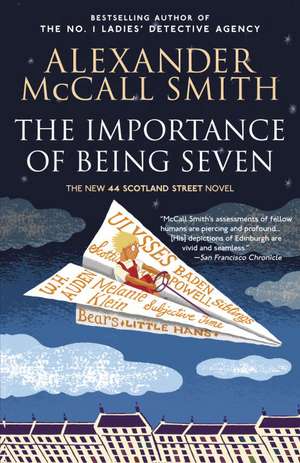

The Importance of Being Seven: 44 Scotland Street Novels, cartea 6

Autor Alexander McCall Smithen Limba Engleză Paperback – 20 aug 2012

The great city of Edinburgh is renowned for its impeccable restraint, so how, then, did the extended family of 44 Scotland Street come to be trembling on the brink of reckless self-indulgence? After seven years and five books, Bertie is—finally!—about to turn seven. But one afternoon he mislays his meddling mother Irene, and learns a valuable lesson: wish-fulfillment can be a dangerous business. Angus and Domenica contemplate whether to give in to romance on holiday in Italy, and even usually down-to-earth Big Lou is overheard discussing cosmetic surgery. Funny, warm, and heartfelt as ever, The Importance of Being Seven offers fresh and wise insights into philosophy and fraternity among Edinburgh's most lovable residents.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 48.00 lei 3-5 săpt. | +23.50 lei 6-10 zile |

| Little Brown Book Group – 2 iun 2011 | 48.00 lei 3-5 săpt. | +23.50 lei 6-10 zile |

| Anchor Books – 20 aug 2012 | 107.92 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 107.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 162

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.65€ • 22.43$ • 17.35£

20.65€ • 22.43$ • 17.35£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 23 aprilie-07 mai

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307739360

ISBN-10: 0307739368

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Anchor Books

Seria 44 Scotland Street Novels

ISBN-10: 0307739368

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Anchor Books

Seria 44 Scotland Street Novels

Notă biografică

Alexander McCall Smith is the author of the international phenomenon The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series, the Isabel Dalhousie series, the Portuguese Irregular Verbs series, the 44 Scotland Street series, and the Corduroy Mansions series. He is professor emeritus of medical law at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and has served with many national and international organizations concerned with bioethics.

www.alexandermccallsmith.com

www.alexandermccallsmith.com

Extras

Chapter 1.

If there was one thing about marriage that surprised Matthew, it was just how quickly he became accustomed to it. There is always the danger that a single person becomes so used to the bachelor or spinster routine that a sudden change in circumstances proves difficult to accommodate. Or so the folk wisdom goes. There is a similar piece of folk wisdom that claims that parents, on launching the last of their children, feel the loss acutely, rapidly declining into the empty-nest syndrome. Both these beliefs are largely false. Married couples – or those choosing to live together as bidies-in (and there is no more appropriate term to express that notion than this couthy Scots expression) – both adjust remarkably quickly to the sharing of bed and board. Indeed, after a few days, in many cases, a previous life is more or less entirely forgotten, and each person believes that he and she, or he and he, or she and she, have lived together for a very long time. In this way Daphnis and Chloë, or Romeo and Juliet, can only too quickly become Darby and Joan, Mr. and Mrs. Bennet, or any other famous domestic couple.

As for the received view about the so-called empty-nest syndrome, like many syndromes, it barely exists. In most cases, parents do feel a slight pang on the leaving of home by their children, but this pang tends to occur before the offspring go, and it is largely a dread of the syndrome itself rather than concern over the actual departure. In this way it is similar to many of the moral panics that afflict an imaginative society from time to time: the fear of what might happen in the future is almost always worse than the future that eventually arrives. So when the child finally goes off to university, or takes a gap year, or moves out to live with coevals, the parents might find themselves feeling strange for a day or two, but often find themselves exhilarated by their new freedom. Very soon it feels entirely normal to have the house to yourself, such is the rapidity with which most people can adjust to new circumstances. And of course if the child has been reluctant to leave home and has remained there until his late twenties, or even beyond, how much more grateful is the parent for this change. Empty-nest syndrome, then, might be redefined altogether, to refer to the feeling of anticipation and longing which affects those whose nest is not emptying quickly enough.

For Matthew and his wife, Elspeth Harmony, the adjustment to married life was both rapid and thoroughly pleasant. Neither had the slightest doubt that the right choice had been made – not only in respect of deciding to get married at all, but also in their choice of partner. Matthew loved Elspeth Harmony – he loved her to the extent that everything that was associated with her, her possessions, her sayings, her friends and connections, were all endowed with a quality of specialness that attached to nothing else. The mug from which she drank her morning coffee was special because her lips had touched it; the tortoiseshell comb that she kept on top of the dressing table was special because it had belonged to Elspeth’s grandmother rather than to any other grandmother; the shopping list that she wrote out to take with her to Valvona & Crolla was special because it was in her handwriting. His affection for her was total, and touching.

For her part, Elspeth could not believe the sheer good fortune that had brought them together. She had always wanted to get married, from her university days onwards, but as the years passed – and she was only twenty-eight at the time of Matthew’s proposal – she had become increasingly concerned that nobody would ask her. There had been one or two boyfriends, but they had not been serious, and her intuitive understanding of this had meant that the relationships had been brief. She saw no point, really, in persisting with a man who would not be with her in a year or two’s time. Why invest emotional energy in something that was not expected to last? In her view that led to disappointment and loss, and this could be avoided by simply not taking up with the man in the first place.

Then Matthew came into her life, and everything changed. It was at such a difficult time, too, very close to that traumatic incident when she had succumbed to her irritation over Olive’s mistreatment of Bertie – Olive had used her junior nurse’s kit to diagnose Bertie as suffering from leprosy – and had pinched Olive’s ear quite hard, something she had wanted to do for some time but which she had refrained from doing because to do so would be contrary to every principle of education and child care she had been taught. The fact that Olive richly deserved this pinch, and indeed might benefit from such a sharp reminder of moral cause and effect, was not a mitigating factor, and she had been obliged to resign from her position at the school. Matthew had been there to save her from the consequences of all this. While other boyfriends might have expressed regret over what she had done, and questioned its wisdom, Matthew sided with her completely and unequivocally, making it clear that he believed that the act of pinching Olive’s ear was a blow for pedagogic sanity.

“There are many children who would be improved by such a pinch,” he observed.

Elspeth thought about this. In normal circumstances she would follow the party line and say that one should never raise a hand to a child or indeed pinch any of its extremities, but mulling over Matthew’s pronouncement she came to the conclusion that she could think of quite a number of children who would benefit from a short, sharp pinch. Tofu, in particular, might be improved by a small amount of judiciously administered physical violence, even if only to stop him spitting at the other children. Perhaps if teachers spat at him he would get the message, but modern educational theory definitely frowned on teachers who spat at their pupils. That was the world in which we lived.

And now all that was behind her. Matthew had rescued her from professional ignominy and given her a new purpose in life. He had showered her with love, and she felt nothing but tenderness for this kind and gentle man, who had given her his name, his home, his fortune, and himself.

If there was one thing about marriage that surprised Matthew, it was just how quickly he became accustomed to it. There is always the danger that a single person becomes so used to the bachelor or spinster routine that a sudden change in circumstances proves difficult to accommodate. Or so the folk wisdom goes. There is a similar piece of folk wisdom that claims that parents, on launching the last of their children, feel the loss acutely, rapidly declining into the empty-nest syndrome. Both these beliefs are largely false. Married couples – or those choosing to live together as bidies-in (and there is no more appropriate term to express that notion than this couthy Scots expression) – both adjust remarkably quickly to the sharing of bed and board. Indeed, after a few days, in many cases, a previous life is more or less entirely forgotten, and each person believes that he and she, or he and he, or she and she, have lived together for a very long time. In this way Daphnis and Chloë, or Romeo and Juliet, can only too quickly become Darby and Joan, Mr. and Mrs. Bennet, or any other famous domestic couple.

As for the received view about the so-called empty-nest syndrome, like many syndromes, it barely exists. In most cases, parents do feel a slight pang on the leaving of home by their children, but this pang tends to occur before the offspring go, and it is largely a dread of the syndrome itself rather than concern over the actual departure. In this way it is similar to many of the moral panics that afflict an imaginative society from time to time: the fear of what might happen in the future is almost always worse than the future that eventually arrives. So when the child finally goes off to university, or takes a gap year, or moves out to live with coevals, the parents might find themselves feeling strange for a day or two, but often find themselves exhilarated by their new freedom. Very soon it feels entirely normal to have the house to yourself, such is the rapidity with which most people can adjust to new circumstances. And of course if the child has been reluctant to leave home and has remained there until his late twenties, or even beyond, how much more grateful is the parent for this change. Empty-nest syndrome, then, might be redefined altogether, to refer to the feeling of anticipation and longing which affects those whose nest is not emptying quickly enough.

For Matthew and his wife, Elspeth Harmony, the adjustment to married life was both rapid and thoroughly pleasant. Neither had the slightest doubt that the right choice had been made – not only in respect of deciding to get married at all, but also in their choice of partner. Matthew loved Elspeth Harmony – he loved her to the extent that everything that was associated with her, her possessions, her sayings, her friends and connections, were all endowed with a quality of specialness that attached to nothing else. The mug from which she drank her morning coffee was special because her lips had touched it; the tortoiseshell comb that she kept on top of the dressing table was special because it had belonged to Elspeth’s grandmother rather than to any other grandmother; the shopping list that she wrote out to take with her to Valvona & Crolla was special because it was in her handwriting. His affection for her was total, and touching.

For her part, Elspeth could not believe the sheer good fortune that had brought them together. She had always wanted to get married, from her university days onwards, but as the years passed – and she was only twenty-eight at the time of Matthew’s proposal – she had become increasingly concerned that nobody would ask her. There had been one or two boyfriends, but they had not been serious, and her intuitive understanding of this had meant that the relationships had been brief. She saw no point, really, in persisting with a man who would not be with her in a year or two’s time. Why invest emotional energy in something that was not expected to last? In her view that led to disappointment and loss, and this could be avoided by simply not taking up with the man in the first place.

Then Matthew came into her life, and everything changed. It was at such a difficult time, too, very close to that traumatic incident when she had succumbed to her irritation over Olive’s mistreatment of Bertie – Olive had used her junior nurse’s kit to diagnose Bertie as suffering from leprosy – and had pinched Olive’s ear quite hard, something she had wanted to do for some time but which she had refrained from doing because to do so would be contrary to every principle of education and child care she had been taught. The fact that Olive richly deserved this pinch, and indeed might benefit from such a sharp reminder of moral cause and effect, was not a mitigating factor, and she had been obliged to resign from her position at the school. Matthew had been there to save her from the consequences of all this. While other boyfriends might have expressed regret over what she had done, and questioned its wisdom, Matthew sided with her completely and unequivocally, making it clear that he believed that the act of pinching Olive’s ear was a blow for pedagogic sanity.

“There are many children who would be improved by such a pinch,” he observed.

Elspeth thought about this. In normal circumstances she would follow the party line and say that one should never raise a hand to a child or indeed pinch any of its extremities, but mulling over Matthew’s pronouncement she came to the conclusion that she could think of quite a number of children who would benefit from a short, sharp pinch. Tofu, in particular, might be improved by a small amount of judiciously administered physical violence, even if only to stop him spitting at the other children. Perhaps if teachers spat at him he would get the message, but modern educational theory definitely frowned on teachers who spat at their pupils. That was the world in which we lived.

And now all that was behind her. Matthew had rescued her from professional ignominy and given her a new purpose in life. He had showered her with love, and she felt nothing but tenderness for this kind and gentle man, who had given her his name, his home, his fortune, and himself.

Recenzii

“Fans of the series (which McCall Smith conducts in daily installments in The Scotsman before book publication) will rejoice at hearing again some of the familiar treads on the fashionable tenement’s stairs. . . . By following an assemblage of characters on and near 44 Scotland Street, McCall Smith manages sidesplitting send-ups of contemporary pretentiousness and wry and often poignant commentary on the roles of chance, cruelty, and fate in our lives. . . . Delightful.”

—Booklist (starred review)

“Life in Scotland Street is a more pleasant, leisurely business than it is for most of the rest of us. . . . There’s plenty of time for idle thoughts, occasional shafts of wit and gentle dissections of absurdity—sometimes all at the same time.” —The Scotsman

“It is that all-prevailing pleasantness, the unfaltering optimism and the gentle pace of life that holds the key to McCall Smith’s success.” —Independent Magazine

“Sweet. . . . Graceful. . . . Wonderful. . . . Gentle but powerfully addicting fiction.”—Entertainment Weekly

“[McCall Smith] is a pro, and he delivers sharp observation, gentle satire . . . as well as the expected romantic complications. . . . [Readers will] relish McCall Smith’s depiction of this place . . . and enjoy his tolerant, good-humored company.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Alexander McCall Smith . . . proves himself a wry but gentle chronicler of humanity and its foibles.” —The Miami Herald

“McCall Smith’s plots offer wit, charm and intrigue in equal doses.” —Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Just about perfect. . . . Contains a healthy helping of McCall Smith’s patented charm.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“McCall Smith’s assessments of fellow humans are piercing and profound. . . . [His] depictions of Edinburgh are vivid and seamless.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Entertaining and witty. . . . A sly send-up of society in Edinburgh.” —Orlando Sentinel

“McCall Smith, a fine writer, paints his hometown of Edinburgh as indelibly as he captures the sunniness of Africa. We can almost feel the mists as we tread the cobblestones.” —The Dallas Morning News

“Alexander McCall Smith is the most genial of writers and the most gentle of satirists. . . . [The] characters are great fun . . . [and] McCall Smith treats all of them with affection.” —Rocky Mountain News

“Irresistible. . . . Smith has rendered another winner, packed with the charming characters, piercing perceptions and shrewd yet generous humor that have become his cachet.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

Descriere

All of the characters are up to new tricks in the sixth novel from this bestselling series. Bertie mislays his meddling mother Irene, Angus and Domenica contemplate whether to give in to romance, and even down-to-earth Big Lou is overheard discussing cosmetic surgery.