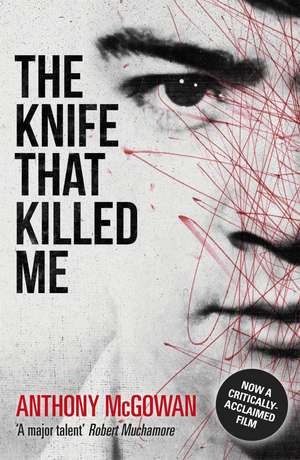

The Knife That Killed Me

Autor Anthony McGowanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 apr 2008

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 47.64 lei 22-33 zile | +16.81 lei 7-13 zile |

| Penguin Random House Children's UK – 3 apr 2008 | 47.64 lei 22-33 zile | +16.81 lei 7-13 zile |

| Ember – 30 sep 2011 | 83.12 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 47.64 lei

Preț vechi: 56.97 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 71

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.12€ • 9.75$ • 7.60£

9.12€ • 9.75$ • 7.60£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-08 aprilie

Livrare express 13-19 martie pentru 26.80 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781862306066

ISBN-10: 1862306060

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: N/A

Dimensiuni: 131 x 198 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Penguin Random House Children's UK

ISBN-10: 1862306060

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: N/A

Dimensiuni: 131 x 198 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Penguin Random House Children's UK

Notă biografică

Anthony McGowan

Extras

ONE

The knife that killed me was a special knife. Its blade was inscribed with magical runes from a lost language, and the metal glimmered with a thousand colors, iridescent as a peacock's tail or the slick of petrol on a puddle. It was made from a meteorite that had plunged to Earth after a journey of a hundred million miles. The heat of entry burned off its crust of brittle rock, leaving a core of iron infused with traces of iridium, titanium, platinum and gold. It was first forged into a blade in ancient Persia, where, set in a hilt of ivory and rhino horn, it passed from hand to hand, worshipped and feared for its power. From Persia it was looted by Alexander the Great, who plucked it from the fingers of King Darius as he lay dying. With Alexander it went to India, where it severed the tendons of the war elephants of Porus, leaving the beasts to vent their fury on the dry earth with thrashing tusks. With Alexander's death the blade was lost to history for three hundred years before it emerged again, taken by Julius Caesar from the royal treasury of Cleopatra. For two centuries it was worn by Roman emperors, and this was the knife that the mad Caligula used to cut the child from his sister's womb. The blade went east again with Valerian, to subdue the barbarians. Five legions perished in the desert, pierced by Parthian arrows, and the emperor's last sight on this earth was his own knife as it cut out his eyes. And for how long did he feel the cool intensity of its edge as he was flayed, and his skin made into a fleshy bag for horseshit, a gory trophy for the victor's temple? From Parthians it passed to Arabs, driven in their conquest by the fervor of faith. And then, at parley, the brave but covetous eye of Richard Coeur de Lion saw the glimmer in Saladin's belt, and that noble Saracen gave up the knife for the sake of peace. With Richard it arrived at last in England. Again a thing of secret worship, dark rites, unholy acts, it moved like an illness of the blood from generation to generation, exquisite but cursed. Until finally, after its journey of eons, it came to me and found its home in my heart.

Yes, a special knife; a cruel knife; a subtle knife.

I wish.

Well, I've had a long time to think about it.

So, now, the truth.

The knife that killed me wasn't a special knife at all. It didn't have any runes on it. Its handle wasn't made of ivory and rhino horn, but cheap black plastic. It was a kitchen knife from Woolworths, and its blade wobbled like a loose tooth.

But it did the job.

TWO

I'm in a gray place now. It could be worse, as hells go. I always thought that hell would burn you, but here I'm cold.

They've told me to write it all out. Why it happened. Why I did it. They said I had to write the truth. But then they said I had to use nice words, so half of this is a lie, because the real words weren't nice at all. You'll have to imagine those words, the ones that aren't nice. I'm sure you can manage that.

No computers here. Just paper and a pen and a big old dictionary, so I get the spelling right.

So I'm remembering. And you know how it is when you remember things. They get jumbled up, the old with the new, the now with the then. But sometimes I find the place and I'm there, utterly, completely, and the people are talking and moving and I'm with them again.

Like now.

I am in a field. The gypsy field, next to the school. There are bodies around me. Bodies entwined. Arms move up and down. Bodies fall. Feet stamp.

When it began, there were shouts, screams, sounds that seemed to come out of the middle of guts and chests, not out of mouths at all. But now there are only the low grunts of hard effort and lower moans from the fallen. And I am among them, but not one of them--one of the fighters, I mean.

I have seen a face I know. Eyes wide with terror. A bigger face is above the face I know, animal hands holding it, the knuckles on the fingers white with the work of it. And the big face has bared its teeth, and the teeth move to the smaller face, the face I know, and the teeth rake down the face, frustrated, not getting purchase, slipping over the tight skin, the shaven head.

I did not know that it would come to this, to biting, to eating.

Are we truly beasts?

I am pushed to the ground, my knees leaving hollows in the wet earth. And I want to move. Either away or toward. To do something. But I have been burned to this spot, like one of the ashy bodies cooked to stillness in Pompeii. Only my eyes can move.

But that's enough for me to see it coming.

The knife that will kill me.

It is in the hand of a boy.

The boy is blurred, but the knife is clear.

He has just taken it from the inside pocket of his blazer.

There is something strange about the way the world is moving. I can see an outline of his arm--I mean, a series of outlines--tracing the motion from his pocket. A ghost trail of outlines. And so there is no motion, just these images, each one still, each one closer to me.

He is coming to kill me.

Now would be a good time to run.

I cannot run.

I am too afraid to run.

But I don't want to die here in the gypsy field, my blood flowing into the wet earth.

I must stop this.

And there is a way.

It comes to me now.

Part of it but not all of it.

Maths. Mr. McHale. A sunny afternoon, and no one listening. He tells us about Zeno's Paradox. The one with fast-running Apollo and the tortoise. If only I could remember it. But I'm not good at school. All I know about is war, battles, armies, learned from my dad, whose chief love is war.

But I have to remember, because the knife is coming. Each moment perfectly still, yet each one closer.

Motion

and

perfect

stillness.

How can that be?

From the Hardcover edition.

The knife that killed me was a special knife. Its blade was inscribed with magical runes from a lost language, and the metal glimmered with a thousand colors, iridescent as a peacock's tail or the slick of petrol on a puddle. It was made from a meteorite that had plunged to Earth after a journey of a hundred million miles. The heat of entry burned off its crust of brittle rock, leaving a core of iron infused with traces of iridium, titanium, platinum and gold. It was first forged into a blade in ancient Persia, where, set in a hilt of ivory and rhino horn, it passed from hand to hand, worshipped and feared for its power. From Persia it was looted by Alexander the Great, who plucked it from the fingers of King Darius as he lay dying. With Alexander it went to India, where it severed the tendons of the war elephants of Porus, leaving the beasts to vent their fury on the dry earth with thrashing tusks. With Alexander's death the blade was lost to history for three hundred years before it emerged again, taken by Julius Caesar from the royal treasury of Cleopatra. For two centuries it was worn by Roman emperors, and this was the knife that the mad Caligula used to cut the child from his sister's womb. The blade went east again with Valerian, to subdue the barbarians. Five legions perished in the desert, pierced by Parthian arrows, and the emperor's last sight on this earth was his own knife as it cut out his eyes. And for how long did he feel the cool intensity of its edge as he was flayed, and his skin made into a fleshy bag for horseshit, a gory trophy for the victor's temple? From Parthians it passed to Arabs, driven in their conquest by the fervor of faith. And then, at parley, the brave but covetous eye of Richard Coeur de Lion saw the glimmer in Saladin's belt, and that noble Saracen gave up the knife for the sake of peace. With Richard it arrived at last in England. Again a thing of secret worship, dark rites, unholy acts, it moved like an illness of the blood from generation to generation, exquisite but cursed. Until finally, after its journey of eons, it came to me and found its home in my heart.

Yes, a special knife; a cruel knife; a subtle knife.

I wish.

Well, I've had a long time to think about it.

So, now, the truth.

The knife that killed me wasn't a special knife at all. It didn't have any runes on it. Its handle wasn't made of ivory and rhino horn, but cheap black plastic. It was a kitchen knife from Woolworths, and its blade wobbled like a loose tooth.

But it did the job.

TWO

I'm in a gray place now. It could be worse, as hells go. I always thought that hell would burn you, but here I'm cold.

They've told me to write it all out. Why it happened. Why I did it. They said I had to write the truth. But then they said I had to use nice words, so half of this is a lie, because the real words weren't nice at all. You'll have to imagine those words, the ones that aren't nice. I'm sure you can manage that.

No computers here. Just paper and a pen and a big old dictionary, so I get the spelling right.

So I'm remembering. And you know how it is when you remember things. They get jumbled up, the old with the new, the now with the then. But sometimes I find the place and I'm there, utterly, completely, and the people are talking and moving and I'm with them again.

Like now.

I am in a field. The gypsy field, next to the school. There are bodies around me. Bodies entwined. Arms move up and down. Bodies fall. Feet stamp.

When it began, there were shouts, screams, sounds that seemed to come out of the middle of guts and chests, not out of mouths at all. But now there are only the low grunts of hard effort and lower moans from the fallen. And I am among them, but not one of them--one of the fighters, I mean.

I have seen a face I know. Eyes wide with terror. A bigger face is above the face I know, animal hands holding it, the knuckles on the fingers white with the work of it. And the big face has bared its teeth, and the teeth move to the smaller face, the face I know, and the teeth rake down the face, frustrated, not getting purchase, slipping over the tight skin, the shaven head.

I did not know that it would come to this, to biting, to eating.

Are we truly beasts?

I am pushed to the ground, my knees leaving hollows in the wet earth. And I want to move. Either away or toward. To do something. But I have been burned to this spot, like one of the ashy bodies cooked to stillness in Pompeii. Only my eyes can move.

But that's enough for me to see it coming.

The knife that will kill me.

It is in the hand of a boy.

The boy is blurred, but the knife is clear.

He has just taken it from the inside pocket of his blazer.

There is something strange about the way the world is moving. I can see an outline of his arm--I mean, a series of outlines--tracing the motion from his pocket. A ghost trail of outlines. And so there is no motion, just these images, each one still, each one closer to me.

He is coming to kill me.

Now would be a good time to run.

I cannot run.

I am too afraid to run.

But I don't want to die here in the gypsy field, my blood flowing into the wet earth.

I must stop this.

And there is a way.

It comes to me now.

Part of it but not all of it.

Maths. Mr. McHale. A sunny afternoon, and no one listening. He tells us about Zeno's Paradox. The one with fast-running Apollo and the tortoise. If only I could remember it. But I'm not good at school. All I know about is war, battles, armies, learned from my dad, whose chief love is war.

But I have to remember, because the knife is coming. Each moment perfectly still, yet each one closer.

Motion

and

perfect

stillness.

How can that be?

From the Hardcover edition.