Extras

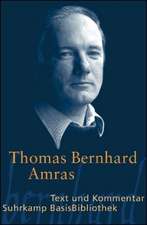

Suicide calculated well in advance, I thought, no spontaneous act of desperation.Even Glenn Gould, our friend and the most im-- portant piano virtuoso of the century, only made it to the age of fifty-one, I thought to myself as I entered the inn.Now of course he didn't kill himself like Wertheimer, but died, as they say, a natural death.Four and a half months in New York and always the Goldberg Variations and the Art of the Fugue, four and a half months of Klavierexerzitien, as Glenn Gould always said only in German, I thought.Exactly twenty-eight years ago we had lived in Leopoldskron and studied with Horowitz and we (at least Wertheimer and I, but of course not Glenn Gould) learned more from Horowitz during a completely rain-drenched summer than during eight previous years at the Mozarteum and the Vienna Academy. Horowitz rendered all our professors null and void. But these dreadful teachers had been necessary to understand Horowitz. For two and a half months it rained without stopping and we locked ourselves in our rooms in Leopoldskron and worked day and night, insomnia (Glenn Gould's) had become a necessary state for us, during the night we worked through what Horowitz had taught us the day before. We ate almost nothing and the whole time never had the backaches we habitually suffered from with our former teachers; with Horowitz the backaches disappeared because we were studying so intensely they couldn't appear. Once our course with Horowitz was over it was clear that Glenn was already a better piano player than Horowitz himself, and from that moment on Glenn was the most important piano virtuoso in the world for me, no matter how many piano players I heard from that moment on, none of them played like Glenn, even Rubinstein, whom I've always loved, wasn't better. Wertheimer and I were equally good, even Wertheimer always said, Glenn is the best, even if we didn't yet dare to say that he was the best player of the century. When Glenn went back to Canada we had actually lost our Canadian friend, we didn't think we'd ever see him again, he was so possessed by his art that we had to assume he couldn't continue in that state for very long and would soon die. But two years after we'd studied together under Horowitz Glenn came to the Salzburg Festival to play the Goldberg Variations, which two years previously he had practiced with us day and night at the Mozarteum and had rehearsed again and again. After the concert the papers wrote that no pianist had ever played the Goldberg Variations so artistically, that is, after his Salzburg concert they wrote what we had already claimed and known two years previously. We had agreed to meet with Glenn after his concert at the Ganshof in Maxglan, an old inn I particularly like. We drank water and didn't say a thing. At this reunion I told Glenn straight off that Wertheimer (who had come to Salzburg from Vienna) and I hadn't believed for a minute we would ever see him, Glenn, again, we were constantly plagued by the thought that Glenn would destroy himself after returning to Canada from Salzburg, destroy himself with his music obsession, with his piano radicalism. I actually said the words piano radicalism to him. My piano radicalism, Glenn always said afterward, and I know that he always used this expression, even in Canada and in America. Even then, almost thirty years before his death, Glenn never loved any composer more than Bach, Handel was his second favorite, he despised Beethoven, even Mozart was no longer the composer I loved above all others when he spoke about him, I thought, as I entered the inn. Glenn never played a single note without humming, I thought, no other piano player ever had that habit. He spoke of his lung disease as if it were his second art. That we had the same illness at the same time and then always came down with it again, I thought, and in the end even Wertheimer got our illness. But Glenn didn't die from this lung disease, I thought. He was killed by the impasse he had played himself into for almost forty years, I thought. He never gave up the piano, I thought, of course not, whereas Wertheimer and I gave up the piano because we never attained the inhuman state that Glenn attained, who by the way never escaped this inhuman state, who didn't even want to escape this inhuman state. Wertheimer had his B~isendorfer grand piano auctioned off in the Dorotheum, I gave away my Steinway one day to the nine-year-old daughter of a schoolteacher in Neukirchen near Altmunster so as not to be tortured by it any longer. The teacher's child ruined my Steinway in the shortest period imaginable, I wasn't pained by this fact, on the contrary, I observed this cretinous destruction of my piano with perverse pleasure. Wertheimer, as he always said, had gone into the human sciences, I had begun my deterioration process. Without my music, which from one day to the next I could no longer tolerate, I deteriorated, without practical music, theoretical music from the very first moment had only a catastrophic effect on me. From one moment to the next I hated my piano, my own, couldn't bear to hear myself play again; I no longer wanted to paw at my instrument. So one day I visited the teacher to announce my gift to him, my Steinway, I'd heard his daughter was musically gifted, I said to him and announced the delivery of my Steinway to his house. I'd convinced myself just in time that personally I wasn't suited for a virtuoso career, I said to the teacher, since I always wanted only the highest in everything I had to separate myself from my instrument, for with it I would surely not reach the highest, as I had suddenly realized, and therefore it was only logical that I should put my piano at the disposal of his gifted daughter, I wouldn't open the cover of my piano even once, I said to the astonished teacher, a rather primitive man who was married to an even more primitive woman, also from Neukirchen near Altmiinster. Naturally I'll take care of the delivery costs! I said to the teacher, whom I've known well since I was a child, just as I've known his simplicity, not to say stupidity. The teacher accepted my gift immediately, I thought as I entered the inn. I hadn't believed in his daughter's talent for a minute; the children of country schoolteachers are always touted as having talent, above all musical talent, but in truth they're not talented in anything, all these children are always completely without talent and even if one of them can blow into a flute or pluck a zither or bang on a piano, that's no proof of talent. I knew I was giving up my expensive instrument to an absolutely worthless individual and precisely for that reason I had it delivered to the teacher. The teacher's daughter took my instrument, one of the very best, one of the rarest and therefore most sought after and therefore also most expensive pianos in the world, and in the shortest period imaginable destroyed it, rendered it worthless. But of course it was precisely this destruction process of my beloved Steinway that I had wanted. Wertheimer went into the human sciences, as he always used to say, I entered my deterioration process, and in bringing my instrument to the teacher's house I had initiated this deterioration process in the best possible manner. Wertheimer continued to play the piano years after I had given my Stein-way to the teacher's daughter because for years he thought himself capable of becoming a piano virtuoso. By the way he played a thousand times better than the majority of our piano virtuosos with public careers, but in the end he wasn't satisfied with being (in the best of cases!) another piano virtuoso like all the others in Europe, and he gave it all up, went into the human sciences. I myself played, I believe, better than Wertheimer, but I would never have been able to play as well as Glenn and for that reason (hence for the same reason as Wertheimer!) I gave up the piano from one moment to the next. I would have had to play better than Glenn, but that wasn't possible, was out of the question, and therefore I gave up playing the piano. I woke up one day in April, I no longer know which one, and said to myself, no more piano. And I never touched the instrument again. I went immediately to the schoolteacher and announced the delivery of my piano. I will now devote myself to philosophical matters, I thought as I walked to the teacher's house, even though of course I didn't have the faintest idea what these philosophical matters might be. I am absolutely not a piano virtuoso, I said to myself, I am not an interpreter, I am not a reproducing artist. No artist at all. The depravity of my idea had appealed to me immediately. The whole time on my way to the teacher's I kept on saying these three words: Absolutely no artist! Absolutely no artist! Absolutely no artist! If I hadn't met Glenn Gould, I probably wouldn't have given up the piano and I would have become a piano virtuoso and perhaps even one of the best piano virtuosos in the world, I thought in the inn. When we meet the very best, we have to give up, I thought. Strangely enough I met Glenn on Monk's Mountain, my childhood mountain. Of course I had seen him previously at the Mozarteum but hadn't exchanged a word with him before our meeting on Monk's Mountain, which is also called Suicide Mountain, since it is especially suited for suicide and every week at least three or four people throw themselves off it into the void. The prospective suicides ride the elevator inside the mountain to the top, take a few steps and hurl themselves down to the city below. Their smashed remains on the street have always fascinated me and I personally (like Wertheimer by the way!) have often climbed or ridden the elevator to the top of Monk's Mountain with the intention of hurling myself into the void, but I didn't throw myself off (nor did Wertheimer!). Several times I had already prepared myself to jump (like Wertheimer!) but didn't jump, like Wertheimer. I turned back. Of course many more people have turned back than have actually jumped, I thought. I met Glenn on Monk's Mountain at the so-called Judge's Peak, where one has the best view of Germany. I spoke first, I said, both of us are studying with Horowitz. Yes, he answered. We looked down at the German plain and Glenn immediately began setting forth his ideas about the Art of the Fugue. I've encountered a highly intelligent man of science, I thought to myself. He had a Rockefeller scholarship, he said. Otherwise his father was a rich man. Hides, furs, he said, speaking German better than our fellow students from the Austrian provinces. Luckily Salzburg is here and not four kilometers farther down in Germany, he said, I wouldn't have gone to Germany. From the first moment ours was a spiritual friendship. The majority of even the most famous piano players haven't a clue about their art, he said. But it's like that in all the arts, I said, just like that in painting, in literature, I said, even philosophers are ignorant of philosophy. Most artists are ignorant of their art. They have a dilettante's notion of art, remain stuck all their lives in dilettantism, even the most famous artists in the world. We understood each other immediately, we were, I have to say it, attracted from the first moment by our differences, which actually were completely opposite in our of course identical conception of art. Just a few days after this encounter on Monk's Mountain we ran into Wertheimer. Glenn, Wertheimer and I, after living separately for the first two weeks, all in completely unacceptable quarters in the Old Town, finally rented a house in Leopoldskron for the duration of our course with Horowitz where we could do what we pleased. In town everything had a debilitating effect on us, the air was unbreathable, the people were intolerable, the damp walls had contaminated us and our instruments. In fact we could only have continued Horowitz's course by moving out of Salzburg, which at bottom is the sworn enemy of all art and culture, a Iicretinous provincial dump with stupid people and cold walls where everything without exception is eventually made cretinous. It was our salvation to pack our worldly goods and move out to Leopoldskron, which at that time was still a green meadow where cows grazed and hundreds of thousands of birds made their home. The town of Salzburg itself, which today is freshly painted even in the darkest corners and is even more disgusting than it was twenty-eight years ago, was and is antagonistic to everything of value in a human being, and in time destroys it; we figured that out at once and took off for Leopoldskron. The people in Salzburg have always been dreadful, like their climate, and when I enter the town today not only is my judgment confirmed, everything is even more dreadful. But to study with Horowitz precisely in this town, the sworn enemy of culture and art, was surely the greatest advantage. We study better in hostile surroundings than in hospitable ones, a student is always well advised to choose a hostile place of study rather than a hospitable one, for the hospitable place will rob him of the better part of his concentration for his studies, the hostile place on the other hand will allow him total concentration, since he must concentrate on his studies to avoid despairing, and to that extent one can absolutely recommend Salzburg, probably like all other so-called beautiful towns, as a place of study, of course only to someone with a strong character, a weak character will inevitably be destroyed in the briefest time. Glenn was charmed by the magic of this town for three days, then he suddenly saw that its magic, as they call it, was rotten, that basically its beauty is disgusting and that the people living in this disgusting beauty are vulgar. The climate in the lower Alps makes for emotionally disturbed people who fall victim to cretinism at a very early age and who in time become malevolent, I said. Whoever lives here knows this if he's honest, and whoever comes here realizes it after a short while and must get away before it's too late, before he becomes just like these cretinous inhabitants, these emotionally disturbed Salzburgers who kill off everything that isn't yet like them with their cretinism.