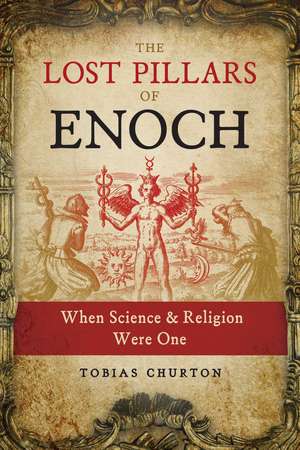

The Lost Pillars of Enoch: When Science and Religion Were One

Autor Tobias Churtonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 mar 2021

• Investigates the Jewish and Egyptian origins of Josephus’s famous story that Seth’s descendants inscribed knowledge on two pillars to save it from global catastrophe

• Reveals how this original knowledge has influenced civilization through Hermetic, Gnostic, Kabbalistic, Masonic, Hindu, and Islamic mystical knowledge

• Examines how “Enoch’s Pillars” relate to the origins of Hermeticism, Freemasonry, Newtonian science, William Blake, and Theosophy

Esoteric tradition has long maintained that at the dawn of human civilization there existed a unified science-religion, a spiritual grasp of the universe and our place in it. The biblical Enoch--also known as Hermes Trismegistus, Thoth, or Idris--was seen as the guardian of this sacred knowledge, which was inscribed on pillars known as Enoch’s or Seth’s pillars.

Examining the idea of the lost pillars of pure knowledge, the sacred science behind Hermetic philosophy, Tobias Churton investigates the controversial Jewish and Egyptian origins of Josephus’s famous story that Seth’s descendants inscribed knowledge on two pillars to save it from global catastrophe. He traces the fragments of this sacred knowledge as it descended through the ages into initiated circles, influencing civilization through Hermetic, Gnostic, Kabbalistic, Masonic, Hindu, and Islamic mystical knowledge. He follows the path of the pillars’ fragments through Egyptian alchemy and the Gnostic Sethites, the Kabbalah, and medieval mystic Ramon Llull. He explores the arrival of the Hermetic manuscripts in Renaissance Florence, the philosophy of Copernicus, Pico della Mirandola, Giordano Bruno, and the origins of Freemasonry, including the “revival” of Enoch in Masonry’s Scottish Rite. He reveals the centrality of primal knowledge to Isaac Newton, William Stukeley, John Dee, and William Blake, resurfacing as the tradition of Martinism, Theosophy, and Thelema. Churton also unravels what Josephus meant when he asserted one Sethite pillar still stood in the “Seiriadic” land: land of Sirius worshippers.

Showing how the lost pillars stand as a twenty-first century symbol for reattaining our heritage, Churton ultimately reveals how the esoteric strands of all religions unite in a gnosis that could offer a basis for reuniting religion and science.

Preț: 99.26 lei

Preț vechi: 130.71 lei

-24% Nou

Puncte Express: 149

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.100€ • 19.72$ • 15.84£

18.100€ • 19.72$ • 15.84£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 07-19 martie

Livrare express 15-21 februarie pentru 63.66 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781644110430

ISBN-10: 1644110431

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: 77 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

ISBN-10: 1644110431

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: 77 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

Notă biografică

Britain’s leading scholar of Western esotericism, Tobias Churton is a world authority on Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Freemasonry, and Rosicrucianism. Holding a master’s degree in theology from Brasenose College, Oxford, he was appointed Honorary Fellow of Exeter University in 2005. The author of many books, including Gnostic Philosophy and Aleister Crowley in America, he lives in the heart of England.

Extras

From Chapter 1. Saving Knowledge from Catastrophe

The World’s First Archaeological Story

Our investigation begins with a little-known story about the origins of knowledge--little known, but not without influence. Arguably the world’s first-ever story of archaeology, Jewish historian Flavius Josephus wrote it down in the 80s of the first century CE, that is about fifty years after his countryman Jesus was crucified.

A guest of the Flavian imperial dynasty in Rome (hence “Flavius”), Josephus hoped his history--The Antiquities of the Jews--would help Greek-reading Romans better appreciate Jewish people. This was timely. Thousands of Jewish warriors had been slaughtered during the previous two decades by imperial troops confronted with religiously motivated “zealots” trying to overthrow Roman jurisdiction. Having joined the rebels himself in the war’s early stages, Josephus shrewdly submitted to Rome, proclaiming that Roman general Vespasian fulfilled the East’s widespread expectation of a savior. When Vespasian established the Flavian dynasty as emperor in 69 CE, Josephus was rewarded.

Josephus wanted Romans to see that not all Jews were persistent rebels, nor were they habitually addicted to crazy beliefs. On the contrary, Josephus’s ancestors were, by Roman standards, rational people maintaining comprehensible traditions, supported by respectable ancient texts compiled long before Roman history began. Confident in his mission, Josephus believed that by presenting Jewish history, he was preserving truth for all humanity because Jewish history took everyone back to the beginning.

The progeny of the first human being is described by Josephus in Antiquities’ second chapter: Adam was not only the Jews’ ancestor, he was the Romans’ ancestor too.

The human race, however, got off to a bad start. Adam’s son Cain fathered a line of wicked reprobates, tainted by Cain’s outrageous murder of pious brother, Abel. Fortunately, Adam and Eve produced a third son, Seth. Seth fathered a lineage distinguished by respect for God and honorable conduct toward God’s creatures: virtues rewarded by access to knowledge of higher things. Josephus describes the higher things in terms of awareness of God, farsighted inventiveness, and knowledge of astronomy.

“They also were the inventors of that peculiar sort of wisdom which is concerned with the heavenly bodies, and their order. And that their inventions might not be lost before they were sufficiently known, upon Adam’s prediction that the world was to be destroyed at one time by the force of fire, and at another time by the violence and quantity of water, they made two pillars, the one of brick, the other of stone: they inscribed their discoveries on them both, that in case the pillar of brick should be destroyed by the flood, the pillar of stone might remain, and exhibit those discoveries to mankind; and also inform them that there was another pillar of brick erected by them. Now this remains in the land of Siriad to this day.”1

Josephus’s compelling image of antediluvian pillars is unique. Nowhere does it appear in the Hebrew Bible. In the Bible, pillars generally receive more bad press than good because Hebrew prophets perennially associated them with idolatry. We don’t know whence Josephus obtained his pillars story, or--and this is important--what the original story may have lost in Josephus’s rather casual telling of it. I say this because Josephus’s history frequently glosses over what non-Jews might find difficult. His pillar story utilizes his distinctive style of ameliorative, urbanely philosophical apologetic. For example, Josephus does not labor the point that conflagrations of fire and water were horrific punishments sent by an outraged deity determined to exterminate humanity--and practically everything else on earth. Josephus may have suspected such an emphasis might offend his Gentile audience with the whiff of unrestrained or fanatical vengeance, and Josephus knew very well that it was apocalyptic predictions of an imminent end of the world in favor of a national savior that had recently motivated Jewish zealots to rise against Rome. Such activities left Jews suspected, and heavily taxed, with Rome commandeering the old temple taxes even after Jerusalem’s temple ceased to exist.

In his rational, universalized account, Josephus’s pillars (or stelae) of brick and stone were erected to preserve discoveries that would otherwise have disappeared in the event of cataclysms, with survivors denied knowledge of them. Josephus emphasizes educative benefit to all human beings. He was aware that predictions of terrestrial deluges were not confined to Jews. Educated Romans knew Greek philosopher Plato’s account in the Timaeus, written in about 360 BCE, of how the great isle of Atlantis sank beneath unforgiving waves. In Plato’s account, an Egyptian priest informs the Greek Solon that Egypt had avoided vastations by flood that ruined other countries thanks to blessed geography and intelligent management of the Nile. Thus, in Josephus’s narrative, Adam’s predictions of water and fire deluges reveal Adam as wise soothsayer rather than unstoical fire-and-brimstone prophet. And, to add a sign of good faith--and a reminder that it was real history about real things the historian was attempting to convey--Josephus added an intriguing codicil: one of the Sethite pillars could still be found.

Given what Josephus says about the stone pillar being the likeliest to survive flood, it was presumably the stone pillar that remained in “Siriad.” That God felt compelled to destroy human beings by water is presented by Josephus as proper punishment invited by provocation: all but Noah and his immediate kin had turned wicked, hell-bent on destruction. God would replace rotten seed with a purified race. Romans understood the necessity for imposing punitive measures upon any who failed to honor divine power, so Josephus was able to tiptoe the tightrope by showing that the Jews’ God likewise favored order, austere justice, and respectful honor, and that God’s punishments, though severe, were nonetheless just, emblematic of an incorruptible judge of humankind. Indeed, the God of Genesis might be compared to stark Roman power as typified in a famous speech Roman historian Tacitus attributed to enemy Caledonian chieftain, Calgacus: “They make a desert, and call it peace.”

The World’s First Archaeological Story

Our investigation begins with a little-known story about the origins of knowledge--little known, but not without influence. Arguably the world’s first-ever story of archaeology, Jewish historian Flavius Josephus wrote it down in the 80s of the first century CE, that is about fifty years after his countryman Jesus was crucified.

A guest of the Flavian imperial dynasty in Rome (hence “Flavius”), Josephus hoped his history--The Antiquities of the Jews--would help Greek-reading Romans better appreciate Jewish people. This was timely. Thousands of Jewish warriors had been slaughtered during the previous two decades by imperial troops confronted with religiously motivated “zealots” trying to overthrow Roman jurisdiction. Having joined the rebels himself in the war’s early stages, Josephus shrewdly submitted to Rome, proclaiming that Roman general Vespasian fulfilled the East’s widespread expectation of a savior. When Vespasian established the Flavian dynasty as emperor in 69 CE, Josephus was rewarded.

Josephus wanted Romans to see that not all Jews were persistent rebels, nor were they habitually addicted to crazy beliefs. On the contrary, Josephus’s ancestors were, by Roman standards, rational people maintaining comprehensible traditions, supported by respectable ancient texts compiled long before Roman history began. Confident in his mission, Josephus believed that by presenting Jewish history, he was preserving truth for all humanity because Jewish history took everyone back to the beginning.

The progeny of the first human being is described by Josephus in Antiquities’ second chapter: Adam was not only the Jews’ ancestor, he was the Romans’ ancestor too.

The human race, however, got off to a bad start. Adam’s son Cain fathered a line of wicked reprobates, tainted by Cain’s outrageous murder of pious brother, Abel. Fortunately, Adam and Eve produced a third son, Seth. Seth fathered a lineage distinguished by respect for God and honorable conduct toward God’s creatures: virtues rewarded by access to knowledge of higher things. Josephus describes the higher things in terms of awareness of God, farsighted inventiveness, and knowledge of astronomy.

“They also were the inventors of that peculiar sort of wisdom which is concerned with the heavenly bodies, and their order. And that their inventions might not be lost before they were sufficiently known, upon Adam’s prediction that the world was to be destroyed at one time by the force of fire, and at another time by the violence and quantity of water, they made two pillars, the one of brick, the other of stone: they inscribed their discoveries on them both, that in case the pillar of brick should be destroyed by the flood, the pillar of stone might remain, and exhibit those discoveries to mankind; and also inform them that there was another pillar of brick erected by them. Now this remains in the land of Siriad to this day.”1

Josephus’s compelling image of antediluvian pillars is unique. Nowhere does it appear in the Hebrew Bible. In the Bible, pillars generally receive more bad press than good because Hebrew prophets perennially associated them with idolatry. We don’t know whence Josephus obtained his pillars story, or--and this is important--what the original story may have lost in Josephus’s rather casual telling of it. I say this because Josephus’s history frequently glosses over what non-Jews might find difficult. His pillar story utilizes his distinctive style of ameliorative, urbanely philosophical apologetic. For example, Josephus does not labor the point that conflagrations of fire and water were horrific punishments sent by an outraged deity determined to exterminate humanity--and practically everything else on earth. Josephus may have suspected such an emphasis might offend his Gentile audience with the whiff of unrestrained or fanatical vengeance, and Josephus knew very well that it was apocalyptic predictions of an imminent end of the world in favor of a national savior that had recently motivated Jewish zealots to rise against Rome. Such activities left Jews suspected, and heavily taxed, with Rome commandeering the old temple taxes even after Jerusalem’s temple ceased to exist.

In his rational, universalized account, Josephus’s pillars (or stelae) of brick and stone were erected to preserve discoveries that would otherwise have disappeared in the event of cataclysms, with survivors denied knowledge of them. Josephus emphasizes educative benefit to all human beings. He was aware that predictions of terrestrial deluges were not confined to Jews. Educated Romans knew Greek philosopher Plato’s account in the Timaeus, written in about 360 BCE, of how the great isle of Atlantis sank beneath unforgiving waves. In Plato’s account, an Egyptian priest informs the Greek Solon that Egypt had avoided vastations by flood that ruined other countries thanks to blessed geography and intelligent management of the Nile. Thus, in Josephus’s narrative, Adam’s predictions of water and fire deluges reveal Adam as wise soothsayer rather than unstoical fire-and-brimstone prophet. And, to add a sign of good faith--and a reminder that it was real history about real things the historian was attempting to convey--Josephus added an intriguing codicil: one of the Sethite pillars could still be found.

Given what Josephus says about the stone pillar being the likeliest to survive flood, it was presumably the stone pillar that remained in “Siriad.” That God felt compelled to destroy human beings by water is presented by Josephus as proper punishment invited by provocation: all but Noah and his immediate kin had turned wicked, hell-bent on destruction. God would replace rotten seed with a purified race. Romans understood the necessity for imposing punitive measures upon any who failed to honor divine power, so Josephus was able to tiptoe the tightrope by showing that the Jews’ God likewise favored order, austere justice, and respectful honor, and that God’s punishments, though severe, were nonetheless just, emblematic of an incorruptible judge of humankind. Indeed, the God of Genesis might be compared to stark Roman power as typified in a famous speech Roman historian Tacitus attributed to enemy Caledonian chieftain, Calgacus: “They make a desert, and call it peace.”

Cuprins

Provenance

A Note about the Timing of This Book

PART ONE

The Lost Pillars in Antiquity

ONE

Saving Knowledge from Catastrophe: The World’s First Archaeological Story

The Nephilim

Where Could Josephus’s Surviving

Pillar Be Found?

TWO

“Sethites” in Egypt?

THREE

Enoch and Hermes: Guardians of Truth

Tracing the Myth

The Emerald Tablet

FOUR

A Sense of Loss Pervades The Fallen Gnostics: Return of the Sethites

FIVE

How Ancient Is the Ancient Theology?

SIX

A Concise History of Religion

SEVEN

From Apocalyptic to Gnosis--and Back to Religion

PART TWO

Hermetic Philosophy

Seeking Concordance, or Reuniting the Fragments

EIGHT

The Unitive Vision

Kabbalah

Ramon Llull (1232-ca. 1316) 100

The Alembic of Florence: Hermetic Philosophy Reborn

NINE

Restoring Harmony: From the Sun to Infinity

Francesco Giorgi: Cosmic Harmony

Copernicus

Giordano Bruno (1548-1600)

TEN

The Lost Pillars of Freemasonry

Late Medieval Evidence for Antediluvian Pillars

Antediluvian Masonry

ELEVEN

Esoteric Masonry and the Mystery of the “Acception”

John Dee and Primal Mathematics

TWELVE

The Return of Enoch

“Out of Egypt I Have Called My Son”

THIRTEEN

Enter Isaac Newton

FOURTEEN

“A History of the Corruption of the Soul of Man”

The Temple of Wisdom

The Ancients Knew Already

Newton and the “Daimon”

FIFTEEN

Antiquarianism: Stukeley and Blake

Stukeley, Freemasonry, and the Prisca Sapientia

SIXTEEN

Blake and the Original Religion

All Religions Are One

SEVENTEEN

From the Enlightenment to Theosophy: Persistence of Antediluvian Unity of Science and Religion

The Tradition

Saint-Yves d’Alveydre

The Secret Doctrine

Problems with Theosophical Influence

EIGHTEEN

The Aim of Religion, the Method of Science: Aleister Crowley and Thelema

Science and Antediluvian Mythology

PART THREE

Paradise Regained?

NINETEEN

Back to the One

Essential Communion in Esoteric Systems

Religion for the Future

TWENTY

Return of the Lost Pillar

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

A Note about the Timing of This Book

PART ONE

The Lost Pillars in Antiquity

ONE

Saving Knowledge from Catastrophe: The World’s First Archaeological Story

The Nephilim

Where Could Josephus’s Surviving

Pillar Be Found?

TWO

“Sethites” in Egypt?

THREE

Enoch and Hermes: Guardians of Truth

Tracing the Myth

The Emerald Tablet

FOUR

A Sense of Loss Pervades The Fallen Gnostics: Return of the Sethites

FIVE

How Ancient Is the Ancient Theology?

SIX

A Concise History of Religion

SEVEN

From Apocalyptic to Gnosis--and Back to Religion

PART TWO

Hermetic Philosophy

Seeking Concordance, or Reuniting the Fragments

EIGHT

The Unitive Vision

Kabbalah

Ramon Llull (1232-ca. 1316) 100

The Alembic of Florence: Hermetic Philosophy Reborn

NINE

Restoring Harmony: From the Sun to Infinity

Francesco Giorgi: Cosmic Harmony

Copernicus

Giordano Bruno (1548-1600)

TEN

The Lost Pillars of Freemasonry

Late Medieval Evidence for Antediluvian Pillars

Antediluvian Masonry

ELEVEN

Esoteric Masonry and the Mystery of the “Acception”

John Dee and Primal Mathematics

TWELVE

The Return of Enoch

“Out of Egypt I Have Called My Son”

THIRTEEN

Enter Isaac Newton

FOURTEEN

“A History of the Corruption of the Soul of Man”

The Temple of Wisdom

The Ancients Knew Already

Newton and the “Daimon”

FIFTEEN

Antiquarianism: Stukeley and Blake

Stukeley, Freemasonry, and the Prisca Sapientia

SIXTEEN

Blake and the Original Religion

All Religions Are One

SEVENTEEN

From the Enlightenment to Theosophy: Persistence of Antediluvian Unity of Science and Religion

The Tradition

Saint-Yves d’Alveydre

The Secret Doctrine

Problems with Theosophical Influence

EIGHTEEN

The Aim of Religion, the Method of Science: Aleister Crowley and Thelema

Science and Antediluvian Mythology

PART THREE

Paradise Regained?

NINETEEN

Back to the One

Essential Communion in Esoteric Systems

Religion for the Future

TWENTY

Return of the Lost Pillar

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Recenzii

“Highly informative, eye-opening, and uplifting, this book takes you on a provocative journey to discover the roots of human knowledge and fills you with hope that we may one day reattain our lost ancient heritage. Since my first encounter with Tobias Churton’s work twenty years ago, I am still amazed by his ability to expertly untangle the complex threads of history.”

“Churton revisits the history of mankind and approaches its attempts to deal with the invisible since the dawn of times with a unique mastery. This book is not only of great erudition but could also be the start of a future global spiritual movement of the digital age.”

“Humanity’s near-manic obsession with lost and rediscovered wisdom is the basis for nearly all esoteric philosophy and practice. Taking the ancient myths and histories as his guide, Churton provides us not only with an interpretation of Enoch and the various ideas around the ‘known-and-lost-wisdom dichotomy’ as they have shaped our views across history, he also gives us a means of shaping and entering the future. It is a future quickly coming upon us, wherein the Pillars of Enoch once again are a depository of the collective wisdom of the past and the guide for a humanity seeking to understand itself and, like Enoch, ‘walk with God.’”

“This ambitious book traces the antediluvian origin of the spiritual wisdom hymned in the Book of Enoch. Churton explores the path of this unifying truth through the teachings of the mystery traditions that have served to initiate humanity ever since. Of central concern to this thesis is that the dichotomy between science and spirit is false. Truth is the unifying bond that excludes only error. The breach between science and religion is an artificial construct that serves to hinder understanding. I highly recommend this book.”

“Churton leads us on a challenging and thought-provoking journey…Churton details traces of what he describes as fragments of this knowledge to be found in such initiated circles as Hermetic, Gnostic, Kabbalistic, Masonic, Hindu and Islamic backgrounds. Furthermore, Churton also strives to show how the esoteric strands of all religions can unite us in a gnosis that could ultimately provide us an opportunity to reunite religion and science as it is meant to be.”

"Overall, I enjoyed The Lost Pillars of Enoch very much. The author presented a large amount of historical information in a balanced and insightful way, along with an occasional dose of humor that lightened the otherwise heavy subject matter. I would recommend this book to anyone interested in esoteric history and hermeticism. I’ve gained insight into how many of our current day ideas about spirituality, prophecy, and science have developed over time, and I’m encouraged that many of the myths we hold dear still have an important message for us."

“Churton revisits the history of mankind and approaches its attempts to deal with the invisible since the dawn of times with a unique mastery. This book is not only of great erudition but could also be the start of a future global spiritual movement of the digital age.”

“Humanity’s near-manic obsession with lost and rediscovered wisdom is the basis for nearly all esoteric philosophy and practice. Taking the ancient myths and histories as his guide, Churton provides us not only with an interpretation of Enoch and the various ideas around the ‘known-and-lost-wisdom dichotomy’ as they have shaped our views across history, he also gives us a means of shaping and entering the future. It is a future quickly coming upon us, wherein the Pillars of Enoch once again are a depository of the collective wisdom of the past and the guide for a humanity seeking to understand itself and, like Enoch, ‘walk with God.’”

“This ambitious book traces the antediluvian origin of the spiritual wisdom hymned in the Book of Enoch. Churton explores the path of this unifying truth through the teachings of the mystery traditions that have served to initiate humanity ever since. Of central concern to this thesis is that the dichotomy between science and spirit is false. Truth is the unifying bond that excludes only error. The breach between science and religion is an artificial construct that serves to hinder understanding. I highly recommend this book.”

“Churton leads us on a challenging and thought-provoking journey…Churton details traces of what he describes as fragments of this knowledge to be found in such initiated circles as Hermetic, Gnostic, Kabbalistic, Masonic, Hindu and Islamic backgrounds. Furthermore, Churton also strives to show how the esoteric strands of all religions can unite us in a gnosis that could ultimately provide us an opportunity to reunite religion and science as it is meant to be.”

"Overall, I enjoyed The Lost Pillars of Enoch very much. The author presented a large amount of historical information in a balanced and insightful way, along with an occasional dose of humor that lightened the otherwise heavy subject matter. I would recommend this book to anyone interested in esoteric history and hermeticism. I’ve gained insight into how many of our current day ideas about spirituality, prophecy, and science have developed over time, and I’m encouraged that many of the myths we hold dear still have an important message for us."