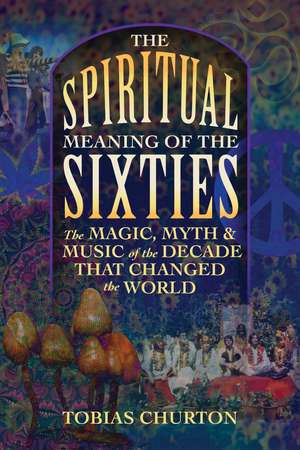

The Spiritual Meaning of the Sixties: The Magic, Myth, and Music of the Decade That Changed the World

Autor Tobias Churtonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 ian 2019

Unveils the spiritual meaning that fueled the artistic, political, and social revolutions of the 1960s

No decade in modern history has generated more controversy and divisiveness than the tumultuous 1960s. For some, the ‘60s were an era of free love, drugs, and social revolution. For others, the Sixties were an ungodly rejection of all that was good and holy. Embarking on a profound search for the spiritual meaning behind the massive social upheavals of the 1960s, Tobias Churton turns a kaleidoscopic lens on religious and esoteric history, industry, science, philosophy, art, and social revolution to identify the meaning behind all these diverse movements.

Engaging with views of mainstream historians, some of whom write off this pivotal decade as heralding an overall decline in moral values and respect for tradition, Churton examines the intricate network of spiritual forces at play in the era. He reveals spiritual principles that united the free love movement, the civil rights and anti-war movements, the hippies’ rejection of materialist culture, and the eventual rise of feminism, gay rights, and environmentalism.

Taking the reader on a long strange trip from crew-cuts and Bermuda shorts to Hair and Woodstock, from liquor to psychedelics, from uncool to cool, and from matter to Soul, Churton shows how the spiritual values of the Sixties are now reemerging, with an astonishing influx of spiritual light, to once again awaken us.

No decade in modern history has generated more controversy and divisiveness than the tumultuous 1960s. For some, the ‘60s were an era of free love, drugs, and social revolution. For others, the Sixties were an ungodly rejection of all that was good and holy. Embarking on a profound search for the spiritual meaning behind the massive social upheavals of the 1960s, Tobias Churton turns a kaleidoscopic lens on religious and esoteric history, industry, science, philosophy, art, and social revolution to identify the meaning behind all these diverse movements.

Engaging with views of mainstream historians, some of whom write off this pivotal decade as heralding an overall decline in moral values and respect for tradition, Churton examines the intricate network of spiritual forces at play in the era. He reveals spiritual principles that united the free love movement, the civil rights and anti-war movements, the hippies’ rejection of materialist culture, and the eventual rise of feminism, gay rights, and environmentalism.

Taking the reader on a long strange trip from crew-cuts and Bermuda shorts to Hair and Woodstock, from liquor to psychedelics, from uncool to cool, and from matter to Soul, Churton shows how the spiritual values of the Sixties are now reemerging, with an astonishing influx of spiritual light, to once again awaken us.

Preț: 136.51 lei

Preț vechi: 205.26 lei

-33% Nou

Puncte Express: 205

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.12€ • 27.27$ • 21.57£

26.12€ • 27.27$ • 21.57£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-09 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781620557112

ISBN-10: 1620557118

Pagini: 672

Ilustrații: 118 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 46 mm

Greutate: 0.77 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

ISBN-10: 1620557118

Pagini: 672

Ilustrații: 118 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 46 mm

Greutate: 0.77 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

Notă biografică

Tobias Churton is a world authority on Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Freemasonry, and Rosicrucianism. Appointed Honorary Fellow of Exeter University in 2005, he holds a master’s degree in Theology from Brasenose College, Oxford, and is the author of many books, including Aleister Crowley in America and Occult Paris. He lives in the heart of England.

Extras

Chapter Fifteen

The Spiritual in Art in the Sixties: The Age of Space

The Real Icon

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) is not a figure one automatically associates with the spiritual in art in the Sixties, but since his untimely death in 1987, Warhol’s spiritual beliefs and the importance to him personally of his religious upbringing have become a little more widely appreciated.

Raised in Pittsburgh, the Warhol family (originally ethnic Lemkos from what is now northeast Slovakia) attended the Saint John Chrysostom Byzantine (or Ruthenian) Church, an experience whose icons, liturgical music, ritual, and vestments left a lifelong impact. Though using the Byzantine Rite of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Ruthenian Church was fully recognized by the Roman Catholic Church. Warhol made regular Mass attendances at the Catholic Saint Vincent Farrer church in Manhattan, sitting at the back, and volunteered at New York’s homeless shelters during the busiest times. I rather think that perhaps only a person who had built his inner life on spiritual foundations could have withstood the many outlandish tremors of his “Factory” life in the Sixties and Seventies without going crazy.

Warhol’s silkscreen diptych Marilyn is probably Warhol’s most, forgive me, “iconic” work, and was first rolled off the process in August 1962, just after Marilyn died in suspicious circumstances a day before Warhol’s thirty-fourth birthday. This might give us a clue to what we ought to mean when we use that very much abused and distorted adjective “iconic.”

Warhol’s church experience was one of the richness of Eastern orthodox architecture. The congregation communicants were used to seeing the saints of the Church in painted portraits surrounded by ornate gold decoration. The paintings were called by the Greek word “icons” (Greek ikōn, an “image” or reflection). These images have a special meaning. When one gazes on a religious icon, one is not worshipping the “image.” That would be idolatry, that is, to place an image before the worship of God. Rather one is enjoined to look spiritually through the image, and pray through the image to the spiritual mystery that the image points toward, inwardly toward, as a sign. The sign is the outer manifestation of an inward reality, a reality that is wholly spiritual, eternal. The icon calls us out of this world and toward the kingdom of God. The individual saint is a being who has brought the light of that kingdom to humankind in such a way that their lives have become a sign to the faithful. An “icon” then, is not simply what we have come to know as an image. It is a visual sacrament.

There seems to me no doubt that Warhol was making an ironic comment, and also a sympathetic, perhaps pitying comment, on the materialism of the predominant culture of the United States, very much in tune with his ironic recognition of commercial art as “art” in the fullest sense nonetheless, if we choose to see it that way. The point about commercial art is that it defies originality insofar as it is mere “image reproduced,” duplicated, or as we say now “cloned.”

However, when we come to the silkscreen image of Marilyn we are seeing two things. First, we are seeing Andy Warhol’s personal response to the undoubtedly tragic demise of the Hollywood “sex goddess,” who was nonetheless a living person, a living, enchanting, troubled soul, and not an image at all. He is elevating her memory by turning her manipulated image from the grip of Hollywood image-manipulators to art, while also saying that all we have now of Marilyn is an image, what passes in an unspiritual world as an “icon,” reproducible and disposable. Life has been lost, and yet the image of Marilyn will go on and on, reproduced on film, in magazines, in the imagination, and so on.

Warhol perhaps has even glimpsed something of the transcendent nature of Marilyn’s personal struggle through life. She said shortly before her death that all she and artists like herself wanted was a chance to twinkle, to reveal the inner star, not merely the outer glamor. She felt the image of Marilyn as something suffocating. Now the world would be plastered with that image.

Clearly, Warhol has been struck by the inverse resonance of the Hollywood image with that of the genuine icon. A genuine icon is a window into heaven. The Hollywood image is a commercial image, superficial, often gaudy, essentially flat, but always spiritually opaque. No light is going to flow through this image to the devoted. The image in cinema is projected onto a screen (a silvery or silvered screen to encourage reflection, not penetration).

I think we do the true icon and Andy Warhol immense disservice when we copy the oft-heard word “iconic” and apply it to this and that reproduced picture, object, or individual. As vulgarly employed today, “iconic” is simply a misleading double for “famous” or “well-known” or “powerful.” Today we hear about a performance being “iconic,” a film being “iconic,” a photo being “iconic.” They are simply images that are reproduced and commonly familiar, and that was inherent to Warhol’s “icons” of the famous. (Remember his famous statement on the transience of democratic fame--everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes--the empty transience of the publicly distributed “selfie”; here today, gone tomorrow. It would only be a matter of time before the “star” him- or herself wanted a silkscreen, not as an ironic comment on their “star-value” or fame and cultural prominence, but as a hip portrait, as their image turned into art by the magician artist Andy Warhol. He would be happy to oblige. One can see the wisdom of the act, for spiritual things are spiritually discerned. Warhol was exposing, even profitably and commercially exposing, reflecting modern life back to itself through the artistic prism of genius.

The Spiritual in Art in the Sixties: The Age of Space

The Real Icon

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) is not a figure one automatically associates with the spiritual in art in the Sixties, but since his untimely death in 1987, Warhol’s spiritual beliefs and the importance to him personally of his religious upbringing have become a little more widely appreciated.

Raised in Pittsburgh, the Warhol family (originally ethnic Lemkos from what is now northeast Slovakia) attended the Saint John Chrysostom Byzantine (or Ruthenian) Church, an experience whose icons, liturgical music, ritual, and vestments left a lifelong impact. Though using the Byzantine Rite of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Ruthenian Church was fully recognized by the Roman Catholic Church. Warhol made regular Mass attendances at the Catholic Saint Vincent Farrer church in Manhattan, sitting at the back, and volunteered at New York’s homeless shelters during the busiest times. I rather think that perhaps only a person who had built his inner life on spiritual foundations could have withstood the many outlandish tremors of his “Factory” life in the Sixties and Seventies without going crazy.

Warhol’s silkscreen diptych Marilyn is probably Warhol’s most, forgive me, “iconic” work, and was first rolled off the process in August 1962, just after Marilyn died in suspicious circumstances a day before Warhol’s thirty-fourth birthday. This might give us a clue to what we ought to mean when we use that very much abused and distorted adjective “iconic.”

Warhol’s church experience was one of the richness of Eastern orthodox architecture. The congregation communicants were used to seeing the saints of the Church in painted portraits surrounded by ornate gold decoration. The paintings were called by the Greek word “icons” (Greek ikōn, an “image” or reflection). These images have a special meaning. When one gazes on a religious icon, one is not worshipping the “image.” That would be idolatry, that is, to place an image before the worship of God. Rather one is enjoined to look spiritually through the image, and pray through the image to the spiritual mystery that the image points toward, inwardly toward, as a sign. The sign is the outer manifestation of an inward reality, a reality that is wholly spiritual, eternal. The icon calls us out of this world and toward the kingdom of God. The individual saint is a being who has brought the light of that kingdom to humankind in such a way that their lives have become a sign to the faithful. An “icon” then, is not simply what we have come to know as an image. It is a visual sacrament.

There seems to me no doubt that Warhol was making an ironic comment, and also a sympathetic, perhaps pitying comment, on the materialism of the predominant culture of the United States, very much in tune with his ironic recognition of commercial art as “art” in the fullest sense nonetheless, if we choose to see it that way. The point about commercial art is that it defies originality insofar as it is mere “image reproduced,” duplicated, or as we say now “cloned.”

However, when we come to the silkscreen image of Marilyn we are seeing two things. First, we are seeing Andy Warhol’s personal response to the undoubtedly tragic demise of the Hollywood “sex goddess,” who was nonetheless a living person, a living, enchanting, troubled soul, and not an image at all. He is elevating her memory by turning her manipulated image from the grip of Hollywood image-manipulators to art, while also saying that all we have now of Marilyn is an image, what passes in an unspiritual world as an “icon,” reproducible and disposable. Life has been lost, and yet the image of Marilyn will go on and on, reproduced on film, in magazines, in the imagination, and so on.

Warhol perhaps has even glimpsed something of the transcendent nature of Marilyn’s personal struggle through life. She said shortly before her death that all she and artists like herself wanted was a chance to twinkle, to reveal the inner star, not merely the outer glamor. She felt the image of Marilyn as something suffocating. Now the world would be plastered with that image.

Clearly, Warhol has been struck by the inverse resonance of the Hollywood image with that of the genuine icon. A genuine icon is a window into heaven. The Hollywood image is a commercial image, superficial, often gaudy, essentially flat, but always spiritually opaque. No light is going to flow through this image to the devoted. The image in cinema is projected onto a screen (a silvery or silvered screen to encourage reflection, not penetration).

I think we do the true icon and Andy Warhol immense disservice when we copy the oft-heard word “iconic” and apply it to this and that reproduced picture, object, or individual. As vulgarly employed today, “iconic” is simply a misleading double for “famous” or “well-known” or “powerful.” Today we hear about a performance being “iconic,” a film being “iconic,” a photo being “iconic.” They are simply images that are reproduced and commonly familiar, and that was inherent to Warhol’s “icons” of the famous. (Remember his famous statement on the transience of democratic fame--everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes--the empty transience of the publicly distributed “selfie”; here today, gone tomorrow. It would only be a matter of time before the “star” him- or herself wanted a silkscreen, not as an ironic comment on their “star-value” or fame and cultural prominence, but as a hip portrait, as their image turned into art by the magician artist Andy Warhol. He would be happy to oblige. One can see the wisdom of the act, for spiritual things are spiritually discerned. Warhol was exposing, even profitably and commercially exposing, reflecting modern life back to itself through the artistic prism of genius.

Cuprins

Acknowledgments

PART ONE

ONE

The Sixties--PHEW!--and Me

TWO

Pro and Anti: The Myth of Progress

Change and Progress

Seeds of ’60s Change

PART TWO

THREE

Defining Terms: What Does “Spiritual Meaning” Mean?

Spirit--What Does It Mean?

How to Discern Spiritual Things

FOUR

As Above, So Below: Models of Spiritual Meaning in History

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin (1743-1803)

Antoine Fabre d’Olivet (1767-1825)

PART THREE

FIVE

Watertown

SIX

1960: Dawn of the Era

SEVEN

Plastic Fantastic

The Great Plastic, Push-Button, Robotic Space Race

“We’re all going on a summer holiday . . .”

EIGHT

Psychology

NINE

Apocalypse Then

Ban the Bomb

Postscript . . . Far Out and Outta Sight

TEN

Education: Loosening the Bonds

Dr. Spock

Game-Change at School

Education in the Movies

ELEVEN

Discomfiting Changes in Theology

We’re More Popular than Jesus Now

John “Hoppy” Hopkins and the London Free School

Dame Frances Yates and the Hermetic Tradition

TWELVE

The Persistence of the Bible

The Bible in Popular Culture

Repression in Russia

From Pilgrimages to Jesus Christ Superstar

THIRTEEN

Civil Rights

James Baldwin

A Few Generally Accepted Facts in Chronological Sequence

PART FOUR

FOURTEEN

The Party’s Over

FIFTEEN

The Spiritual in Art in the Sixties: The Age of Space

The Artists

The Real Icon

Yves Klein (1928-1962)--Prophet

SIXTEEN

The Spiritual in Orchestral, Film, and Jazz Music

SEVENTEEN

What the World Needs Now Is Love: The Spirit in Pop Music

EIGHTEEN

Cinema

Cinema as It Was--in Just One Day

Spiritual Values in Sixties Cinema

NINETEEN

Television

Spiritual Television?

A Day of TV in 1968

PART FIVE

TWENTY

Woman Freeing Helen “Birds”

TWENTY-ONE

Sexual Revolution

Flower Power

Pornography

Homosexuality

TWENTY-TWO

Psychedelics

Hashish

LSD-25

Hip Gnosis

TWENTY-THREE

India

Vedanta and Advaita

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (ca.1918-2008)

Ravi Shankar (1920-2012)

Swami Bhaktivedanta (1896-1977)

TWENTY-FOUR

Shiva: The Destroyer, the Uniter, the Transformer

PART SIX

TWENTY-FIVE

The Turning Point--1965: The Aeon of the Child Made Manifest

TWENTY-SIX

Feeling Groovy: The West Coast

The Human Be-In and Gathering of the Tribes

The Levitation of the Pentagon

TWENTY-SEVEN

The Beast and the Six Six Sixties

The Beast in Sixties America

Wasserman’s Quest

PART SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

New York

New York’s Art and Literature Scene

Axis Bold as Love

TWENTY-NINE

1969 I: No Peace for the Wicked

The Amsterdam Bed-In

THIRTY

1969 II: So Near and Yet So Far, or . . . What the Hell Went Wrong? Not So Easy Rider

And Suddenly, It Was the Seventies

THIRTY-ONE

The Spiritual Meaning of the 1960s

We Blew It

Easy Rider

Notes

Bibliography

Index

PART ONE

ONE

The Sixties--PHEW!--and Me

TWO

Pro and Anti: The Myth of Progress

Change and Progress

Seeds of ’60s Change

PART TWO

THREE

Defining Terms: What Does “Spiritual Meaning” Mean?

Spirit--What Does It Mean?

How to Discern Spiritual Things

FOUR

As Above, So Below: Models of Spiritual Meaning in History

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin (1743-1803)

Antoine Fabre d’Olivet (1767-1825)

PART THREE

FIVE

Watertown

SIX

1960: Dawn of the Era

SEVEN

Plastic Fantastic

The Great Plastic, Push-Button, Robotic Space Race

“We’re all going on a summer holiday . . .”

EIGHT

Psychology

NINE

Apocalypse Then

Ban the Bomb

Postscript . . . Far Out and Outta Sight

TEN

Education: Loosening the Bonds

Dr. Spock

Game-Change at School

Education in the Movies

ELEVEN

Discomfiting Changes in Theology

We’re More Popular than Jesus Now

John “Hoppy” Hopkins and the London Free School

Dame Frances Yates and the Hermetic Tradition

TWELVE

The Persistence of the Bible

The Bible in Popular Culture

Repression in Russia

From Pilgrimages to Jesus Christ Superstar

THIRTEEN

Civil Rights

James Baldwin

A Few Generally Accepted Facts in Chronological Sequence

PART FOUR

FOURTEEN

The Party’s Over

FIFTEEN

The Spiritual in Art in the Sixties: The Age of Space

The Artists

The Real Icon

Yves Klein (1928-1962)--Prophet

SIXTEEN

The Spiritual in Orchestral, Film, and Jazz Music

SEVENTEEN

What the World Needs Now Is Love: The Spirit in Pop Music

EIGHTEEN

Cinema

Cinema as It Was--in Just One Day

Spiritual Values in Sixties Cinema

NINETEEN

Television

Spiritual Television?

A Day of TV in 1968

PART FIVE

TWENTY

Woman Freeing Helen “Birds”

TWENTY-ONE

Sexual Revolution

Flower Power

Pornography

Homosexuality

TWENTY-TWO

Psychedelics

Hashish

LSD-25

Hip Gnosis

TWENTY-THREE

India

Vedanta and Advaita

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (ca.1918-2008)

Ravi Shankar (1920-2012)

Swami Bhaktivedanta (1896-1977)

TWENTY-FOUR

Shiva: The Destroyer, the Uniter, the Transformer

PART SIX

TWENTY-FIVE

The Turning Point--1965: The Aeon of the Child Made Manifest

TWENTY-SIX

Feeling Groovy: The West Coast

The Human Be-In and Gathering of the Tribes

The Levitation of the Pentagon

TWENTY-SEVEN

The Beast and the Six Six Sixties

The Beast in Sixties America

Wasserman’s Quest

PART SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

New York

New York’s Art and Literature Scene

Axis Bold as Love

TWENTY-NINE

1969 I: No Peace for the Wicked

The Amsterdam Bed-In

THIRTY

1969 II: So Near and Yet So Far, or . . . What the Hell Went Wrong? Not So Easy Rider

And Suddenly, It Was the Seventies

THIRTY-ONE

The Spiritual Meaning of the 1960s

We Blew It

Easy Rider

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“The Spiritual Meaning of the Sixties is Tobias Churton’s most personal book. . . . A wonderfully capacious interpretation of the tumultuous decade.”

"All in all, Churton has written a fascinating and important book, and it is a must-read for any reader with an interest in the 60's or contemporary culture generally."

"All in all, Churton has written a fascinating and important book, and it is a must-read for any reader with an interest in the 60's or contemporary culture generally."

Descriere

Unveils the spiritual meaning that fueled the artistic, political, and social revolutions of the 1960s