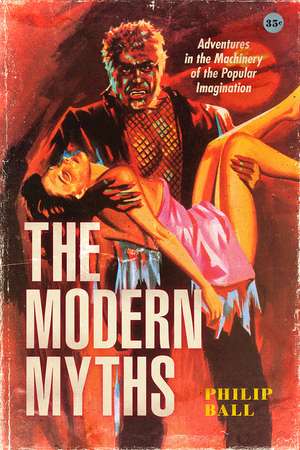

The Modern Myths: Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular Imagination

Autor Philip Ballen Limba Engleză Paperback – 19 oct 2022

Myths are usually seen as stories from the depths of time—fun and fantastical, but no longer believed by anyone. Yet, as Philip Ball shows, we are still writing them—and still living them—today. From Robinson Crusoe and Frankenstein to Batman, many stories written in the past few centuries are commonly, perhaps glibly, called “modern myths.” But Ball argues that we should take that idea seriously. Our stories of Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Sherlock Holmes are doing the kind of cultural work that the ancient myths once did. Through the medium of narratives that all of us know in their basic outline and which have no clear moral or resolution, these modern myths explore some of our deepest fears, dreams, and anxieties. We keep returning to these tales, reinventing them endlessly for new uses. But what are they really about, and why do we need them? What myths are still taking shape today? And what makes a story become a modern myth?

In The Modern Myths, Ball takes us on a wide-ranging tour of our collective imagination, asking what some of its most popular stories reveal about the nature of being human in the modern age.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 135.19 lei 3-5 săpt. | +33.92 lei 7-11 zile |

| University of Chicago Press – 19 oct 2022 | 135.19 lei 3-5 săpt. | +33.92 lei 7-11 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 226.93 lei 3-5 săpt. | +32.46 lei 7-11 zile |

| University of Chicago Press – 21 mai 2021 | 226.93 lei 3-5 săpt. | +32.46 lei 7-11 zile |

Preț: 135.19 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 203

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.87€ • 28.09$ • 21.73£

25.87€ • 28.09$ • 21.73£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Livrare express 18-22 martie pentru 43.91 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780226823843

ISBN-10: 0226823849

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 60 halftones

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: University of Chicago Press

Colecția University of Chicago Press

ISBN-10: 0226823849

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 60 halftones

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: University of Chicago Press

Colecția University of Chicago Press

Notă biografică

Philip Ball is a freelance writer and broadcaster and was an editor at Nature for more than twenty years. He writes regularly in the scientific and popular media and has written many books on the interactions of the sciences, the arts, and wider culture, including H2O: A Biography of Water, Bright Earth: The Invention of Colour, The Music Instinct, and Curiosity: How Science Became Interested in Everything. His book Critical Mass won the 2005 Aventis Prize for Science Books. Ball is also a presenter of Science Stories, the BBC Radio 4 series on the history of science. He trained as a chemist at the University of Oxford and as a physicist at the University of Bristol. He is the author, most recently, of The Book of Minds: How to Understand Ourselves and Other Beings, from Animals to AI to Aliens, also published by the University of Chicago Press. He lives in London.

Extras

HOW CAN A MYTH BE MODERN?

We can start almost anywhere, and there’s no virtue in being highbrow about it. So why not with the 2004 movie Van Helsing, starring Hugh Jackman as the famous vampire-hunter? Aside from his name and calling, this youthful, dark-locked, brawny action hero has nothing in common with Dracula’s venerable nemesis in Bram Stoker’s novel. It’s not only the bloodsucking count he’s pursuing but a legion of monsters that includes Frankenstein’s creature and the brutish Mr. Hyde. We know we are in safe hands here, for Jackman and his screen lover, Kate Beckinsale, are genre stalwarts, much as Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, Boris Karloff, and Bela Lugosi were in their day. The texture of the movie is familiar too: comic-strip gothic, lit by moonlight and bristling with razor-fanged CGI beasts, the framing and aesthetic echoing the graphic novels of Frank Miller and Alan Moore. The imagery is iconic: here is Dracula’s castle, much as it was in the 1931 Lugosi movie directed by Tod Browning. There is Frankenstein’s electrified laboratory, full of sparks and shadows, where Karloff ’s creature rose up in the same year. And here comes the flat-headed monster himself, his patchwork skull apt to fly open, in slapstick fashion, to reveal a sparking brain. We forgive Van Helsing for becoming a werewolf and killing his paramour; heroes these days are prone to such things.

Van Helsing is a stupendously silly homage, about as scary and unsettling as a soap opera, and I rather enjoyed it.

There doesn’t, though, appear to be much we can learn about our modern myths from this sort of good-natured romp, with its relentless computer-game dynamic, cheap sentimentalism, and makeshift, Frankensteinian mosaic of motifs. Surely it does for these myths only what Ray Harryhausen did for the classical myths of Greece, turning them into a parade of cinematic effects with not a care for coherence or poetry. (I don’t mean that in a bad way.)

Still, you know what I’m talking about, don’t you? You know what Van Helsing, in its clumsy, carefree fashion, is up to. You know that the seam it is exploiting, the language it is using, is indeed that of myth.

I hope I am not being condescending when I suspect that few among Van Helsing’s target audience—hormonal adolescents eager for violent action, sexy vampires, and spectacle—will have read Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. These are stories that everyone knows without having to go to that trouble. They have seeped into our consciousness, replete with emblematic visuals, before we reach adulthood. I met Robinson Crusoe in a black-and-white French television series from the 1960s, in which nothing much seemed to happen save for the discovery of that momentous footprint in the sand; like many of my generation, I can hum the theme tune today. Frankenstein arrived as a glowin-the-dark model kit of the Karloff incarnation, arms outstretched to claim his next victim. (It was not actually “Frankenstein,” of course, but his monster, although the box didn’t tell me that.) The stingray alien craft of George Pal’s 1953 movie The War of the Worlds were ominous enough to distract us from the wires from which they dangled. Dracula—well, he was Christopher Lee, everyone knew that.

This cultural osmosis is how we learn our modern myths. For myths are what these stories are, and to suggest (as some purists do) that the Hammer films or Hollywood adaptations traduced the “real” story is to miss their point. In this book I propose that the Western world has, over the past three centuries or so, produced narratives that have as authentic a claim to mythic status as the psychological dramas of Oedipus, Medea, Narcissus, and Midas and the ancient universal myths of creation, flood, redemption, and heroism.

Myths have no authors, although they must have an origin. They escape those origins (and their originators) not simply because they are constantly retold with an accumulation of mutations, appendages, and misconceptions. Rather, their creators have given body to stories for which retellings are deemed necessary. What is it in these special tales that compels us so compulsively to return to them? Each age finds different answers, and this too is in the nature of myth.

Why are we still making myths? Why do we need new myths? And what sort of stories attain this status?

In posing these questions and seeking answers, I shall need to make some bold proposals about the nature of storytelling, the condition of modernity, and the categories of literature. I don’t claim that any of these suggestions is new in itself, but the notion of a modern myth can give them some focus and unity. We have been skating around that concept for many years now, and I can’t help wondering if some of the reticence to acknowledge and accept it stems from puzzlement, and perhaps too a sense of unease, that Van Helsing is a part of the story. Not just that movie, but also the likes of I Was a Teenage Werewolf and Zombie Apocalypse, as well as children’s literature and detective pulp fiction, not to mention queer theory, alien abduction fantasies, video games, body horror, and artificial intelligence.

In short, there are a great many academic silos, cultural prejudices, and intellectual exclusion zones trammeling an exploration of our mythopoeic impulse. Even in 2019, for example, a celebrated literary novelist dipping his toe into a robot narrative could suppose that real science fiction deals in “travelling at 10 times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots,” as opposed to “looking at the human dilemmas of being close up.” It is precisely because our modern myths go everywhere that they earn that label, and for this same reason we fail to see (or resist seeing) them for what they are. As classical myths did for the cultures that conceived them, modern myths help us to frame and come to terms with the conditions of our existence.

Evidently, this is not all about literary books. Myths are promiscuous; they were postmodern before the concept existed, infiltrating and being shaped by popular culture. To discern their content, we need to look at comic books and B-movies as well as at Romantic poetry and German Expressionist cinema. We need to peruse the scientific literature, books of psychoanalysis, and made-for-television melodramas. Myths are not choosy about where they inhabit, and I am not going to be choosy about where to find them.

We can start almost anywhere, and there’s no virtue in being highbrow about it. So why not with the 2004 movie Van Helsing, starring Hugh Jackman as the famous vampire-hunter? Aside from his name and calling, this youthful, dark-locked, brawny action hero has nothing in common with Dracula’s venerable nemesis in Bram Stoker’s novel. It’s not only the bloodsucking count he’s pursuing but a legion of monsters that includes Frankenstein’s creature and the brutish Mr. Hyde. We know we are in safe hands here, for Jackman and his screen lover, Kate Beckinsale, are genre stalwarts, much as Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, Boris Karloff, and Bela Lugosi were in their day. The texture of the movie is familiar too: comic-strip gothic, lit by moonlight and bristling with razor-fanged CGI beasts, the framing and aesthetic echoing the graphic novels of Frank Miller and Alan Moore. The imagery is iconic: here is Dracula’s castle, much as it was in the 1931 Lugosi movie directed by Tod Browning. There is Frankenstein’s electrified laboratory, full of sparks and shadows, where Karloff ’s creature rose up in the same year. And here comes the flat-headed monster himself, his patchwork skull apt to fly open, in slapstick fashion, to reveal a sparking brain. We forgive Van Helsing for becoming a werewolf and killing his paramour; heroes these days are prone to such things.

Van Helsing is a stupendously silly homage, about as scary and unsettling as a soap opera, and I rather enjoyed it.

There doesn’t, though, appear to be much we can learn about our modern myths from this sort of good-natured romp, with its relentless computer-game dynamic, cheap sentimentalism, and makeshift, Frankensteinian mosaic of motifs. Surely it does for these myths only what Ray Harryhausen did for the classical myths of Greece, turning them into a parade of cinematic effects with not a care for coherence or poetry. (I don’t mean that in a bad way.)

Still, you know what I’m talking about, don’t you? You know what Van Helsing, in its clumsy, carefree fashion, is up to. You know that the seam it is exploiting, the language it is using, is indeed that of myth.

I hope I am not being condescending when I suspect that few among Van Helsing’s target audience—hormonal adolescents eager for violent action, sexy vampires, and spectacle—will have read Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. These are stories that everyone knows without having to go to that trouble. They have seeped into our consciousness, replete with emblematic visuals, before we reach adulthood. I met Robinson Crusoe in a black-and-white French television series from the 1960s, in which nothing much seemed to happen save for the discovery of that momentous footprint in the sand; like many of my generation, I can hum the theme tune today. Frankenstein arrived as a glowin-the-dark model kit of the Karloff incarnation, arms outstretched to claim his next victim. (It was not actually “Frankenstein,” of course, but his monster, although the box didn’t tell me that.) The stingray alien craft of George Pal’s 1953 movie The War of the Worlds were ominous enough to distract us from the wires from which they dangled. Dracula—well, he was Christopher Lee, everyone knew that.

This cultural osmosis is how we learn our modern myths. For myths are what these stories are, and to suggest (as some purists do) that the Hammer films or Hollywood adaptations traduced the “real” story is to miss their point. In this book I propose that the Western world has, over the past three centuries or so, produced narratives that have as authentic a claim to mythic status as the psychological dramas of Oedipus, Medea, Narcissus, and Midas and the ancient universal myths of creation, flood, redemption, and heroism.

Myths have no authors, although they must have an origin. They escape those origins (and their originators) not simply because they are constantly retold with an accumulation of mutations, appendages, and misconceptions. Rather, their creators have given body to stories for which retellings are deemed necessary. What is it in these special tales that compels us so compulsively to return to them? Each age finds different answers, and this too is in the nature of myth.

Why are we still making myths? Why do we need new myths? And what sort of stories attain this status?

In posing these questions and seeking answers, I shall need to make some bold proposals about the nature of storytelling, the condition of modernity, and the categories of literature. I don’t claim that any of these suggestions is new in itself, but the notion of a modern myth can give them some focus and unity. We have been skating around that concept for many years now, and I can’t help wondering if some of the reticence to acknowledge and accept it stems from puzzlement, and perhaps too a sense of unease, that Van Helsing is a part of the story. Not just that movie, but also the likes of I Was a Teenage Werewolf and Zombie Apocalypse, as well as children’s literature and detective pulp fiction, not to mention queer theory, alien abduction fantasies, video games, body horror, and artificial intelligence.

In short, there are a great many academic silos, cultural prejudices, and intellectual exclusion zones trammeling an exploration of our mythopoeic impulse. Even in 2019, for example, a celebrated literary novelist dipping his toe into a robot narrative could suppose that real science fiction deals in “travelling at 10 times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots,” as opposed to “looking at the human dilemmas of being close up.” It is precisely because our modern myths go everywhere that they earn that label, and for this same reason we fail to see (or resist seeing) them for what they are. As classical myths did for the cultures that conceived them, modern myths help us to frame and come to terms with the conditions of our existence.

Evidently, this is not all about literary books. Myths are promiscuous; they were postmodern before the concept existed, infiltrating and being shaped by popular culture. To discern their content, we need to look at comic books and B-movies as well as at Romantic poetry and German Expressionist cinema. We need to peruse the scientific literature, books of psychoanalysis, and made-for-television melodramas. Myths are not choosy about where they inhabit, and I am not going to be choosy about where to find them.

Recenzii

"Ball does an impressive job with the literary histories behind each iconic title, assembling a set of origin stories rich in cultural history and imagination. . . . To Ball, mythic writing is where the conditions of irrationality, superstition, and enchantment persist: forms of wonder that depend on the disconnect between what we know for sure and what we simply believe."

"Myths themselves commonly embody the religious beliefs of ancient or preliterate peoples, but Ball suggests that we are still generating them. Subtitled Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular Imagination, his book, The Modern Myths, cogently argues for the originality and potent cultural resonance of Robinson Crusoe, Victor Frankenstein and his creature, Sherlock Holmes, Dracula, alien invaders like those of H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds, Batman, and even zombies. All these soon escaped from their original creators’ control and are now at large, their stories capable of multiple and even conflicting interpretations. The key to the mythic mode, asserts Ball, is ambivalence."

"A persistent myth of the modern West is that it has outgrown the need for myths, along with religion, magic and other 'irrational' beliefs of the benighted past. This triumphalist story of rationality was proclaimed by Enlightenment philosophers and documented by later social scientists; through the 1990s, 'the disenchantment of the world' became an incantation within the parched groves of academe. Ball is among those who counter that enchantment and modernity aren’t incompatible. In The Modern Myths, he makes a persuasive case that myth isn’t gone but can be found in stories closer to our current obsessions such as science and technology, globalization and individual psychology. . . . His provocations to debate are among the book's many pleasures."

"Ball makes a case that myths are not things of the past. Modern myths, Ball posits, are still being written and are just as crucial and revelatory as ancient ones."

"From acclaimed popular science writer Ball comes a fresh look at the modern legends that shape our perception of reality. Stories like Dracula, Batman, Sherlock Holmes, or Frankenstein, which we keep retelling and reimagining, are doing the kind of cultural work that ancient myths and fairy tales once did. How do they operate, and why do we need them? And what tales will come to be the new myths of the future?"

"Modern myths—of which Ball identifies seven, starting with Robinson Crusoe and ending with Batman—are not, despite their origins in specific texts, so much singular narratives as ‘evolving web[s] of many stories—interweaving, interacting, contradicting each other’—but with one thing in common: ‘[A] rugged, elemental, irreducible kernel charged with the magical power of generating versions of the story.’ This fecund capacity to produce new narratives is what allows these myths to do their ‘cultural work’: they ‘erect a rough-hewn framework on which to hang our anxieties, fears, and dreams.’"

“Aquarians love people, and they love their stories, too—that’s one of the reasons they make such great writers (and readers). They will be fascinated and inspired by this book, which investigates many of our ‘modern myths’—what they are, why we love them, and why we need them, from Dracula to Sherlock Holmes. They’re all stories we know—but what do they know about us?”

Most Anticipated Books of May 2021

"To Ball, 'myth' doesn’t just mean a set of ancient stories—Greek mythology as one canon, Norse another, etc. Instead, it refers to a mode of story-making that still exists today. In fact, it seems to be a way of telling stories that we can’t help but enact; Ball believes these modern myths are coming into being almost without our realizing it, and that, by recognizing their existence and being more alert to their power, we might better understand ourselves."

"Ball’s fascinating study concerns itself with seven stories from the eighteenth century through the present that have become 'modern myths,' a concept he blueprints in the opening chapter and elaborates along the way. . . . An admirable amount of research has clearly gone into each of the seven case studies. The material is well-organized and the writing lucid, often snappy. . . . Our exuberantly guided tour of these modern myths is enlivened by fun facts."

"Funny and insightful reading for anybody interested in popular culture and how it was impacted by the current hunger for myths and their modern incarnations."

"Ball is an exceptional writer and researcher, but with this and his other books, he demonstrates that there is an audience and appetite, beyond the field’s confines, for works that tell sophisticated stories about science and society. The book also affirms the value of the humanities for understanding the field’s central problems."

"There are different ideas about what makes a myth exactly, but most agree that myths tell us something fundamental about human nature. We’re familiar with Greek myths, but Philip Ball wonders what more recent stories may have been elevated to mythic status, even if we might not think of them in those specific terms. Ball, a writer on science, here ascends the cliff and climbs into the cave to wrestle with those unscientific, literary creations that have become embedded in our collective psyche."

"Admirably clear-headed."

"Compulsively readable literary criticism. . . . Valid and persuasive. . . . Worth a look."

"Ball begins by making the case for the modern myth, highlighting the attributes that allow some stories to grow beyond their origins and disregarding notions that the modern cannot be mythical. Ball shows how these characters and stories have seeped into collective consciousness—so much so that one no longer has to read the original texts to understand the stories or characters. He further illustrates how modern myths have been reimagined and repackaged to reflect modern worries, allowing the reader to come to terms with the conditions of existence. The Modern Myths is well researched, as evidenced by twenty-two pages of notes, eight pages of bibliography, and footnotes and images scattered throughout. Ball draws parallels between original works and modern interpretations and representations in films, television, comic books, and B-movies. Readers will find Ball’s arguments clear and easy to understand. Highly recommended."

"For those of us who care about mythopoetic fiction, this is a ringing endorsement of the significance of what we study."

“Ball always brings your attention to things that were in your field of vision all along but you just hadn't noticed. He gives you the tools to investigate and dig deeper. The Modern Myths makes the world a more thrilling place. This is a book filled with delight and curiosity that will change the way you see the stories that are all around you.”

“The Modern Myths is a very impressive piece of writing. It is sharp. It is witty. It is deeply insightful in too many places to list. Ball’s erudition on these topics is extraordinary, really. How did he read all of this? And how did he see all of these movies? Does he sleep? A very fine study of seven really important stories in modern literature, fantasy, and film.”