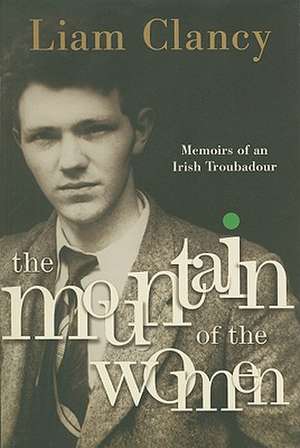

The Mountain of the Women: Memoirs of an Irish Troubadour

Autor Liam Clancyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2002

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Listen Up (2002)

Following in the grand tradition of such Irish memoirs as Angela’s Ashes and Are You Somebody?, Liam Clancy relates his life’s story in a raucously funny and star-studded account of moving from provincial Ireland to the bars and clubs of New York City, to the cusp of fame as a member of Tommy Makem and the Clancy Brothers. Born in 1935, the eleventh out of as many children, young Liam was a naive and innocent lad of the Old Country. His memories of childhood include bounding over hills, streams, and the occasional mountain, getting lost, and eventually found, and making mischief in the way of a typical Irish boy.

As an aimless nineteen-year-old, Clancy met a strange and wonderfully energetic lover of music, Ms. Diane Guggenheim, an American heiress. She and a colleague from America had set out to record regional Irish folk music, and their undertaking led them to Carrick-on-Suir in the shadow of Slievenamon, "The Mountain of the Women," where Mammie Clancy had been known to carry a tune or two in her kitchen. Guggenheim fell for young Liam and swept him along on her travels through the British Isles, the American Appalachians, and finally Greenwich Village, the undisputed Mecca for aspiring artists of every ilk in the late 1950s.

Clancy was in New York to become an actor. But on the side, he played and sang with his brothers, Paddy and Tom, and fellow countryman Tommy Makem, in pubs like the legendary White Horse Tavern. In the heady atmosphere of the Village, Clancy’s life was a party filled with music, sex, and McSorley’s. His friendships with then-unknown artists such as Bob Dylan, Maya Angelou, Robert Redford, Lenny Bruce, Pete Seeger and Barbra Streisand form the backdrop of the charming adventures of a small-town boy making it big in the biggest of cities.

In music circles, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem are known as the Beatles of Irish music. The band’s music continues to play on jukeboxes in pubs and bars, in living rooms of folk music fans, and in Irish American homes throughout the country. Liam Clancy’s lively memoir captures their wild adventures on the road to fame and fortune, and brings to life a man who never lets himself off the hook for his sins, and happily views his success as a blessing.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 109.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 164

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.98€ • 22.80$ • 17.64£

20.98€ • 22.80$ • 17.64£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385520508

ISBN-10: 0385520506

Pagini: 294

Ilustrații: 8 PAGE INSERT

Dimensiuni: 155 x 231 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0385520506

Pagini: 294

Ilustrații: 8 PAGE INSERT

Dimensiuni: 155 x 231 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

LIAM CLANCY was a founding member of The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, whose records have sold millions of copies over the past forty years. He lives in County Waterford, Ireland, and continues to record and perform in concerts around the world.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Not far from my hometown in Ireland there is a mountain called Slievenamon. It is shaped like a beautiful female breast and on its summit sits a cairn of stones, like a nipple. The name Slievenamon comes from the Gaelic, Sliabh na mBan, the mountain of the women. My blood tells me that my origins are there.

Some say the mountain got its name from the profile it presents when seen from Carrick-on-Suir, the town in which I was born. A more intriguing story tells how the legendary giant, Fionn McCool, would need a new wife each year and, because of his mighty demands, would put all the candidates vying for the job to a test. On a certain day of the year they would all race to the top of Slievenamon and back. The winner, he considered, might have the stamina to cope with his virility for the next year.

Our town is in the valley of the river Suir at the top of the tide that surges all the way up the estuary from the sea, thirty or so miles to the east. The wooded hills rise up from the river to the south to good farmland that stretches the eight miles or so to the ice-carved Comeragh Mountains. To the north the land rises to a plain that reaches for the beautiful breast of Slievenamon and its foothills, four miles away. The valley to the west is known as the Golden Vale, the land of milk and honey. It is small wonder that wave after wave of invaders wanted to get their hands on this rich land. Just recently, archaeologists have started excavating local tumulus mounds as old as or older than Newgrange, which predates the pyramids of Egypt by some two centuries. Two groups of burial monuments called portal dolmens attest to the fact that humans have settled in this place since the Stone Age. There is something fascinating and humbling, as the Carrick poet Michael Coady dwells on in his writing, about occupying spaces which others have vacated and which we, in turn, will vacate for the next generation. In the nature of things the people of each generation assume, of course, that theirs is the only important one. In time, others will realize that they weren't the first ones here and try, perhaps, to unearth some knowledge of us.

On the south-facing slope of Slievenamon stand the ruins of a castle or great house of the 1700s with the remnants of walled gardens and old outlying walls with gable shapes of long-gone buildings. These ruins speak to us, as a well-known song about the place does, of the time when Cill Cais, the great house, was full of life and industry, of plenty and hospitality. The song also tells of the Great Lady--an Deigh Bhean, as she was called in the Irish--who held sway over this revered and wondrous place.

An ait ud 'na g'conaiodh an Deigh Bhean,

Fuair gradam is meidhir thar mna.

--"Cill Cais" (old song)

What shall we do for timber?

The last of the woods is down.

Kilcash and the house of its glory

And the bell of the house is gone,

The spot where that lady waited

Who shamed all women for grace

When earls came sailing to greet her

And Mass was said in the place.

--"Kilcash" (translated by Frank O'Connor)

I learned that song at school as a boy in Carrick-on-Suir. Like all songs of past times, it was peopled with what I thought of as mythical figures, but one day I happened on a scene which brought the myth and the reality together before my very eyes. As my kids and I wandered about the ruins of Kilcash, a man who lived in one of the cottages nearby recognized me as one of the Clancys.

"You're one of the singers, aren't you? Liam, isn't it? I knew your father, Bob, from the insurance business. He used to call you by the English version of your name, Willie. Well, now, this is good. Do you see the old church down there below the castle? That's been there since the seventh century and inside that church there's a headstone with your name on it--William Clancy. The Board of Works are trying to save what's left of the early church, and the big stones are pulled back from the underground vault." There was a hint of awe in his voice. "They've cleared away decades of debris. If you go down the steps and let yer eyes get used to the dark, you'll see herself stretched out there, an Deigh Bhean, the Great Lady, Lady Iveagh, with two other skeletons: her husband, a Richard Butler I believe he'd be, and the bishop of the time, whose name I can't recall. Their lead coffins were taken by the IRA to make bullets during the Black and Tan War."

When the three kids and I went down into the chamber of the dead, sure enough, there on the rubble of the vault floor were the bones, red and moldering, of the woman I used to sing about in school. The kids and I gazed a long moment in fascination before beating a retreat back up to daylight.

As with many ruined churches in Ireland, the graves of what I suppose to be the "important people" are inside the church walls, while the lesser folk have to lie outside in the adjoining graveyard. As we made our way up to the main part of the church, an old man wandering from headstone to toppling headstone said, "There's class distinction everywhere, even in the graveyard." Searching through the gravestones within the ruined walls, trying to decipher the weatherworn names, I came upon the one my friend had referred to. Since it was made from hard slate and leaning away from the worst of the weather, it was easy to make out the names.

Among them was one that read: Willm Clancy Died May 11, 1735. He had died two hundred years and nearly four months before I was born. I don't believe in reincarnation, at least not like that, but it did make me stop for a moment and wonder.

Who was he, then? I thought, this namesake of mine. Possibly a brehon lawyer or bard attached to the big house. The Clancys were reputed to be brehon lawyers or bards since medieval times. Lady Iveagh may have been William Clancy's patroness. In my own case it was a wealthy American lady who took me under her patronage and started my career off in the New World. I wanted to know more about the man. Was he a relative? What was life like in his day? I wished he could tell his story, but the grave is a silent place.

The words of the Greek poet Nikos Kazantzakis came to mind: "When [a man] dies, that aspect of the universe which is his own particular vision and the unique play of his mind also crashes in ruins forever."

I hear a challenge in that. So I take up the challenge and tell my story for what it's worth.

Now in my sixties, I live in a house full of joyous activity, a house I'd always dreamed of building in my boyhood, full of family and friends and people I love. But as I start my story, I lie in a hospital bed because my sixtieth birthday party was full of song and food and music and drink. At some point in the night (I learned later it was four in the morning) I saw someone dive into the swimming pool outside, and since it was my birthday, I dressed appropriately, in my birthday suit, and declaimed:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

With that I plunged into the lung-chilling water. Excess, I'm afraid, has always been one of the little failings of my life.

With a lung full of pneumonia, the oxygen hissing through my mask and the antibiotics coursing through my veins, I ruminate upon it all. Like the overtures of the operas my father would entertain us with when we were children, snatches of song and story weave in and out through my fever. I feel like Jose Ferrer as the dying Toulouse-Lautrec in the film Moulin Rouge. All the friends and characters and events of my life come flitting by my bed. Back again comes the "smell of the crowd and the roar of the grease paint," the countless nights on countless stages through forty years of acting, singing, and general foolishness.

In Carnegie Hall a fellow drops his hat from the top balcony to cheers and roars of laughter from the crowd. Tommy Makem shouts up at him, "Aren't you lucky your head isn't in it?"

The cross-eyed girls in Dundee, front row, center aisle at Caird Hall, every time breaking us up with laughter.

The little dancer who joined us on the stage of the Opera House in Chicago, blinded by the lights and dancing closer and closer to the edge of the stage before disappearing into the depths of the orchestra pit.

The great nights when you could do no wrong and the awful nights when, alone onstage, transfixed by thousands of eyes, you're gripped by cold panic and the overwhelming desire to flee.

Here they come now trooping through the door to say their last farewells, the ones I knew in the real world and those I knew only in the realm of imagination. Come one and all. Come round my bed and in delirium we'll sing a chorus.

And it's no, nay, never (clap clap clap clap)

No, nay, never no more (clap clap)

Will I play the wild rover (clap)

No, never no more.

The fire in my head becomes an ember. I drift toward sleep, smiling.

Life spreads out like rings on a lake from the place where the stone was dropped. The first rings are mother, father, family, house. Then your street, your town, the characters, the smells, sounds, tastes, the first sense of place. The rings widen to the valley, the hills and mountains, then beyond to the sea, the plains, the next town, the city, and on to the big world. They lose their physical qualities then and become rings of the imagination, of philosophy, religion, spirituality, and creativity, until they dissipate on the far shores of the eternal mysteries.

I think my first memory was of being in a pram outside our door on William Street on a sunny day. I can see the sides of the pram and hear sounds of laughing and fighting coming from inside the door. There is a pipe on the wall beside the pram. Across the street I see a big purple window and, reflected in it, bright houses. Later I put it together that the pipe is a water chute. The big glass window is Verrington's meat shop with the big purple blind pulled down (it must have been Sunday), and the reflections were the houses on our side of the street.

They called me "the old cow's calf," "the shakin's of the bag," eleventh child of Robert Joseph Clancy and Johanna McGrath Clancy, born when she was forty-seven years old. Of the nine surviving children--one had died before I was born, another when I was six months old--I was the afterthought, six years younger than my sister Peg, who, it was supposed, was definitely the last. My mother blamed my conception on a feed of cockles. Cockles! In January?

After I was born my parents must still have shared a bed for a few years at least because--(good God, how it comes back even now!)--dimly, dimly I see it, feel it, a longing, a need, sobbing in the dark, no answer, no comfort, the longing, the need. Then the arms. I'm raised up. Close warmth. Laid down now in the safest of all places, warm and safe in the nest between two bodies. The safest, snuggest, warmest nest I'll ever know, in the middle, between my father and mother in the back room bed. Fear all gone. Here I can snuggle in forever, in the lovely dark.

Gray light out there. Climb over a big body, out on the floorboards, up on tippy-toes, over to the light--the gray light, the dawn world.

How many times, in later life, will I try to see our backyard with the same eyes, capture the same mood of the yard at dawn as I first saw it? But it's useless. Now I know that that's a wall, those are flower beds and vegetable beds. Lilac is the name of that bush and I know the sweet smell of it. Beyond the wall is the nuns' orchard, which I'll be too timid to rob (not like my brother Bobby), the orchard where I'll see and later be part of the May Procession full of blossoms and lovely joyful hymns of May and the little girls in white and the smell of newness off the boys' clothes. No, try as I will, I'll never see that yard again with the first-time eyes of a child at dawn. I have put it all in a bigger context now and its boundaries won't ever retreat.

What I will learn soon, though, is how to manipulate my parents. I'll hear my father say, "Aw, look! The big salty tears." My God! I can taste them now! "Aw, sure come here, boy! Here in the middle for the golden fiddle." The salty tears will be well used, and the first words I'll string together will be "hock bockilly a poor Willie a haboo bed a mammy house." In other words, "a hot bottle (of milk) for poor Willie to go asleep in mammie's bed."

The bottle must not always have been convenient because I believe I was breast-fed until I was about four. Never lost the taste for it, either.

But in that back room, too, I learned fear. Sometimes I would lie awake between the sleeping bodies of my father and mother and there through the open door was a black tunnel up to somewhere I'd never been. I'd lie in a state of panic and wait for something awful to come down the tunnel from the attic. I would spend hours waiting for one of my parents to wake up, but not daring to wake them for the bigger fear, the fear that the salty tears might not work next time.

The attic, or the garret, as we called it, took on a whole new aspect when I got to know it. It became our castle, our hideout, our rainy-day world, a continent of endless adventure. There were nine of us at home still when I was three or four. Lili was the eldest, then Leish and Cait (twins), Paddy, Tom, Bobby and Joan (more twins), Peg, then me. Willie! God how I hated the name! But my mother insisted on calling me after Father Willie Doyle, a chaplain of the First World War and my mother's hero. It wasn't till years later, when I lived in Dublin and had a walk-on part in The Playboy of the Western World with Cyril Cusack and Siobhan McKenna, that I shed the name like a festered skin. On the first day of rehearsal on the Gaiety stage Cyril Cusack asked me, "What's your name, lad?"

From the Hardcover edition.

Not far from my hometown in Ireland there is a mountain called Slievenamon. It is shaped like a beautiful female breast and on its summit sits a cairn of stones, like a nipple. The name Slievenamon comes from the Gaelic, Sliabh na mBan, the mountain of the women. My blood tells me that my origins are there.

Some say the mountain got its name from the profile it presents when seen from Carrick-on-Suir, the town in which I was born. A more intriguing story tells how the legendary giant, Fionn McCool, would need a new wife each year and, because of his mighty demands, would put all the candidates vying for the job to a test. On a certain day of the year they would all race to the top of Slievenamon and back. The winner, he considered, might have the stamina to cope with his virility for the next year.

Our town is in the valley of the river Suir at the top of the tide that surges all the way up the estuary from the sea, thirty or so miles to the east. The wooded hills rise up from the river to the south to good farmland that stretches the eight miles or so to the ice-carved Comeragh Mountains. To the north the land rises to a plain that reaches for the beautiful breast of Slievenamon and its foothills, four miles away. The valley to the west is known as the Golden Vale, the land of milk and honey. It is small wonder that wave after wave of invaders wanted to get their hands on this rich land. Just recently, archaeologists have started excavating local tumulus mounds as old as or older than Newgrange, which predates the pyramids of Egypt by some two centuries. Two groups of burial monuments called portal dolmens attest to the fact that humans have settled in this place since the Stone Age. There is something fascinating and humbling, as the Carrick poet Michael Coady dwells on in his writing, about occupying spaces which others have vacated and which we, in turn, will vacate for the next generation. In the nature of things the people of each generation assume, of course, that theirs is the only important one. In time, others will realize that they weren't the first ones here and try, perhaps, to unearth some knowledge of us.

On the south-facing slope of Slievenamon stand the ruins of a castle or great house of the 1700s with the remnants of walled gardens and old outlying walls with gable shapes of long-gone buildings. These ruins speak to us, as a well-known song about the place does, of the time when Cill Cais, the great house, was full of life and industry, of plenty and hospitality. The song also tells of the Great Lady--an Deigh Bhean, as she was called in the Irish--who held sway over this revered and wondrous place.

An ait ud 'na g'conaiodh an Deigh Bhean,

Fuair gradam is meidhir thar mna.

--"Cill Cais" (old song)

What shall we do for timber?

The last of the woods is down.

Kilcash and the house of its glory

And the bell of the house is gone,

The spot where that lady waited

Who shamed all women for grace

When earls came sailing to greet her

And Mass was said in the place.

--"Kilcash" (translated by Frank O'Connor)

I learned that song at school as a boy in Carrick-on-Suir. Like all songs of past times, it was peopled with what I thought of as mythical figures, but one day I happened on a scene which brought the myth and the reality together before my very eyes. As my kids and I wandered about the ruins of Kilcash, a man who lived in one of the cottages nearby recognized me as one of the Clancys.

"You're one of the singers, aren't you? Liam, isn't it? I knew your father, Bob, from the insurance business. He used to call you by the English version of your name, Willie. Well, now, this is good. Do you see the old church down there below the castle? That's been there since the seventh century and inside that church there's a headstone with your name on it--William Clancy. The Board of Works are trying to save what's left of the early church, and the big stones are pulled back from the underground vault." There was a hint of awe in his voice. "They've cleared away decades of debris. If you go down the steps and let yer eyes get used to the dark, you'll see herself stretched out there, an Deigh Bhean, the Great Lady, Lady Iveagh, with two other skeletons: her husband, a Richard Butler I believe he'd be, and the bishop of the time, whose name I can't recall. Their lead coffins were taken by the IRA to make bullets during the Black and Tan War."

When the three kids and I went down into the chamber of the dead, sure enough, there on the rubble of the vault floor were the bones, red and moldering, of the woman I used to sing about in school. The kids and I gazed a long moment in fascination before beating a retreat back up to daylight.

As with many ruined churches in Ireland, the graves of what I suppose to be the "important people" are inside the church walls, while the lesser folk have to lie outside in the adjoining graveyard. As we made our way up to the main part of the church, an old man wandering from headstone to toppling headstone said, "There's class distinction everywhere, even in the graveyard." Searching through the gravestones within the ruined walls, trying to decipher the weatherworn names, I came upon the one my friend had referred to. Since it was made from hard slate and leaning away from the worst of the weather, it was easy to make out the names.

Among them was one that read: Willm Clancy Died May 11, 1735. He had died two hundred years and nearly four months before I was born. I don't believe in reincarnation, at least not like that, but it did make me stop for a moment and wonder.

Who was he, then? I thought, this namesake of mine. Possibly a brehon lawyer or bard attached to the big house. The Clancys were reputed to be brehon lawyers or bards since medieval times. Lady Iveagh may have been William Clancy's patroness. In my own case it was a wealthy American lady who took me under her patronage and started my career off in the New World. I wanted to know more about the man. Was he a relative? What was life like in his day? I wished he could tell his story, but the grave is a silent place.

The words of the Greek poet Nikos Kazantzakis came to mind: "When [a man] dies, that aspect of the universe which is his own particular vision and the unique play of his mind also crashes in ruins forever."

I hear a challenge in that. So I take up the challenge and tell my story for what it's worth.

Now in my sixties, I live in a house full of joyous activity, a house I'd always dreamed of building in my boyhood, full of family and friends and people I love. But as I start my story, I lie in a hospital bed because my sixtieth birthday party was full of song and food and music and drink. At some point in the night (I learned later it was four in the morning) I saw someone dive into the swimming pool outside, and since it was my birthday, I dressed appropriately, in my birthday suit, and declaimed:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

With that I plunged into the lung-chilling water. Excess, I'm afraid, has always been one of the little failings of my life.

With a lung full of pneumonia, the oxygen hissing through my mask and the antibiotics coursing through my veins, I ruminate upon it all. Like the overtures of the operas my father would entertain us with when we were children, snatches of song and story weave in and out through my fever. I feel like Jose Ferrer as the dying Toulouse-Lautrec in the film Moulin Rouge. All the friends and characters and events of my life come flitting by my bed. Back again comes the "smell of the crowd and the roar of the grease paint," the countless nights on countless stages through forty years of acting, singing, and general foolishness.

In Carnegie Hall a fellow drops his hat from the top balcony to cheers and roars of laughter from the crowd. Tommy Makem shouts up at him, "Aren't you lucky your head isn't in it?"

The cross-eyed girls in Dundee, front row, center aisle at Caird Hall, every time breaking us up with laughter.

The little dancer who joined us on the stage of the Opera House in Chicago, blinded by the lights and dancing closer and closer to the edge of the stage before disappearing into the depths of the orchestra pit.

The great nights when you could do no wrong and the awful nights when, alone onstage, transfixed by thousands of eyes, you're gripped by cold panic and the overwhelming desire to flee.

Here they come now trooping through the door to say their last farewells, the ones I knew in the real world and those I knew only in the realm of imagination. Come one and all. Come round my bed and in delirium we'll sing a chorus.

And it's no, nay, never (clap clap clap clap)

No, nay, never no more (clap clap)

Will I play the wild rover (clap)

No, never no more.

The fire in my head becomes an ember. I drift toward sleep, smiling.

Life spreads out like rings on a lake from the place where the stone was dropped. The first rings are mother, father, family, house. Then your street, your town, the characters, the smells, sounds, tastes, the first sense of place. The rings widen to the valley, the hills and mountains, then beyond to the sea, the plains, the next town, the city, and on to the big world. They lose their physical qualities then and become rings of the imagination, of philosophy, religion, spirituality, and creativity, until they dissipate on the far shores of the eternal mysteries.

I think my first memory was of being in a pram outside our door on William Street on a sunny day. I can see the sides of the pram and hear sounds of laughing and fighting coming from inside the door. There is a pipe on the wall beside the pram. Across the street I see a big purple window and, reflected in it, bright houses. Later I put it together that the pipe is a water chute. The big glass window is Verrington's meat shop with the big purple blind pulled down (it must have been Sunday), and the reflections were the houses on our side of the street.

They called me "the old cow's calf," "the shakin's of the bag," eleventh child of Robert Joseph Clancy and Johanna McGrath Clancy, born when she was forty-seven years old. Of the nine surviving children--one had died before I was born, another when I was six months old--I was the afterthought, six years younger than my sister Peg, who, it was supposed, was definitely the last. My mother blamed my conception on a feed of cockles. Cockles! In January?

After I was born my parents must still have shared a bed for a few years at least because--(good God, how it comes back even now!)--dimly, dimly I see it, feel it, a longing, a need, sobbing in the dark, no answer, no comfort, the longing, the need. Then the arms. I'm raised up. Close warmth. Laid down now in the safest of all places, warm and safe in the nest between two bodies. The safest, snuggest, warmest nest I'll ever know, in the middle, between my father and mother in the back room bed. Fear all gone. Here I can snuggle in forever, in the lovely dark.

Gray light out there. Climb over a big body, out on the floorboards, up on tippy-toes, over to the light--the gray light, the dawn world.

How many times, in later life, will I try to see our backyard with the same eyes, capture the same mood of the yard at dawn as I first saw it? But it's useless. Now I know that that's a wall, those are flower beds and vegetable beds. Lilac is the name of that bush and I know the sweet smell of it. Beyond the wall is the nuns' orchard, which I'll be too timid to rob (not like my brother Bobby), the orchard where I'll see and later be part of the May Procession full of blossoms and lovely joyful hymns of May and the little girls in white and the smell of newness off the boys' clothes. No, try as I will, I'll never see that yard again with the first-time eyes of a child at dawn. I have put it all in a bigger context now and its boundaries won't ever retreat.

What I will learn soon, though, is how to manipulate my parents. I'll hear my father say, "Aw, look! The big salty tears." My God! I can taste them now! "Aw, sure come here, boy! Here in the middle for the golden fiddle." The salty tears will be well used, and the first words I'll string together will be "hock bockilly a poor Willie a haboo bed a mammy house." In other words, "a hot bottle (of milk) for poor Willie to go asleep in mammie's bed."

The bottle must not always have been convenient because I believe I was breast-fed until I was about four. Never lost the taste for it, either.

But in that back room, too, I learned fear. Sometimes I would lie awake between the sleeping bodies of my father and mother and there through the open door was a black tunnel up to somewhere I'd never been. I'd lie in a state of panic and wait for something awful to come down the tunnel from the attic. I would spend hours waiting for one of my parents to wake up, but not daring to wake them for the bigger fear, the fear that the salty tears might not work next time.

The attic, or the garret, as we called it, took on a whole new aspect when I got to know it. It became our castle, our hideout, our rainy-day world, a continent of endless adventure. There were nine of us at home still when I was three or four. Lili was the eldest, then Leish and Cait (twins), Paddy, Tom, Bobby and Joan (more twins), Peg, then me. Willie! God how I hated the name! But my mother insisted on calling me after Father Willie Doyle, a chaplain of the First World War and my mother's hero. It wasn't till years later, when I lived in Dublin and had a walk-on part in The Playboy of the Western World with Cyril Cusack and Siobhan McKenna, that I shed the name like a festered skin. On the first day of rehearsal on the Gaiety stage Cyril Cusack asked me, "What's your name, lad?"

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- Listen Up Editor's Choice, 2002