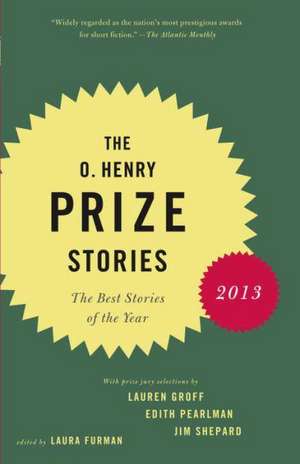

The O. Henry Prize Stories: American Moses: Pen / O. Henry Prize Stories

Editat de Laura Furmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 9 sep 2013

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 96.12 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Random House Value Publishing – 31 aug 2003 | 96.12 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Anchor Books – 9 sep 2013 | 127.20 lei 17-23 zile | +11.02 lei 6-10 zile |

Preț: 127.20 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 191

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.34€ • 25.11$ • 20.31£

24.34€ • 25.11$ • 20.31£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-07 martie

Livrare express 18-22 februarie pentru 21.01 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345803252

ISBN-10: 0345803256

Pagini: 475

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:2013

Editura: Anchor Books

Seria Pen / O. Henry Prize Stories

ISBN-10: 0345803256

Pagini: 475

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:2013

Editura: Anchor Books

Seria Pen / O. Henry Prize Stories

Notă biografică

Laura Furman, series editor of The O. Henry Prize Stories since 2003, is the winner of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts for her fiction. The author of seven books, including her recent story collection The Mother Who Stayed, she taught writing for many years at the University of Texas at Austin. She lives in Central Texas.

Extras

Excerpted from Your Duck Is My Duck

Way back—oh, not all that long ago, actually, just a couple of years, but back before I’d gotten a glimpse of the gears and levers and pulleys that dredge the future up from the earth’s core to its surface—I was going to a lot of parties.

And at one of these parties there was a couple, Ray and Christa, who hung out with various people I sort of knew, or, anyhow, whose names I knew. We’d never had much of a conversation, just hey there, kind of thing, but I’d seen them at parties over the years and at that particular party they seemed to forget that we weren’t actually friends ourselves.

Ray and Christa had a lot of money, a serious quantity, and they were also both very good-looking, so they could live the way they felt like living. Sometimes they split up, and one of them, usually Ray, was with someone else for a while, always a splashy, public business that made their entourage scatter like flummoxed chickens, but inevitably they got back together, and afterwards, you couldn’t detect a scar.

Ray had a chummy arm around me and Christa was swaying to the music, which was almost drowned out by the din of voices in the metallic room, and smiling absently in my direction. I was a little taken aback that I was being, I guess, anointed, but it was up to them how well they knew you, and I could only assume that their cordiality meant either that something good had happened to me which was not yet perceptible to me but was already perceptible to them, or else that something good was about to happen to me.

So, we were talking, shouting, really, over the noise, and after a bit I realized that what they were saying meant that they now owned my painting Blue Hill.

They owned Blue Hill? I had given Blue Hill to Graham once, in a happy moment, and he must have sold it to them when he up and moved to Barcelona. Blue Hill is not a bad painting, in my opinion, it’s one of my best, still, the expression that I could feel taking charge of my face came and went without making trouble for anyone, thanks to the fact that, obviously, there were a lot of people in the room for Ray and Christa to be looking at, other than me.

How are you these days, they asked, and at this faint suggestion that they’d been monitoring me, a great wave of childish gratitude and relief washed over me, dissolving my dignity and leaving me stranded in self-pity.

Why did I keep going to these stupid parties? Night after night, parties, parties—was I hoping to meet someone? No one met people in person any longer—you couldn’t hear what they were saying. Except for the younger women, who had piercing, high voices and sounded like Donald Duck, from whom they had evidently learned to talk. When had that happened? An adaptation? You could certainly hear them.

It was getting on my nerves and making me feel old. I’m exhausted, I told Ray and Christa. I can’t sleep. I can’t take the winter. I’m sick of my day job at Howard’s photo studio, but on the other hand, Howard’s having some problems—last week there were three of us, and this week there are two, and I’m scared I’m going to be the next to go. And as I told them that I was frightened, that I was sick of the winter and my job, I understood how deeply, deeply sick of the winter and my job, how frightened, I really was.

Yeah, that’s terrible, they said. Well, why don’t you come stay with us? We’re taking off for our beach place on Wednesday. There’s plenty of room, and you can paint. We love your work. It’s a great place to work, everyone says so, really serene. The light is great, the vistas are great.

I’m having some trouble painting these days, I said, I’m not really, I don’t know.

Hey, everyone needs some downtime, they said; you’ll be inspired, everyone who visits is inspired. You won’t have to deal with anything. There’s a cook. You can lie around in the sun and recuperate. You can take donkey rides down into the town, or there are bicycles or the driver. What languages do you speak? Well, it doesn’t matter. You won’t need to speak any.

Naturally I assumed they’d forget all about their invitation, so I was startled, the day after the party, to get an email from Christa, asking when I could get away. One of their people would deal with the flights. I could stay as long as I liked, she said, and if I wanted to send heavy working materials on ahead, that would be fine. Lots of their guests did that. It could get cool at night, so I should bring something warm, and if I wanted to hike, I should bring boots, because snakes, as I knew, could be an issue, though insects were generally not. I would not need a visa these days, so not to worry about that, and not to worry about Wi-Fi—that was all set up.

I doubted that anybody else who visited them would not know exactly how to prepare, and yet there was Christa, informing me so tactfully of everything, like snakes and visas, that I’d need to know about, by pretending that of course I’d already have thought of those things. A week or so later, a messenger brought a plane ticket up the five flights of stairs to my little apartment, which was when it dawned on me that the good thing Ray and Christa had perceived happening to me was that they now owned one of my paintings, which meant, obviously, that it most likely was, or would soon be, worth acquiring.

My job at Howard’s studio expired, along with the studio itself, at the end of the following month, just in time to save Howard and me from my quitting right before I got on the plane. At least it was no problem to sublet my apartment, even at a little profit, to a guy who liked cats, because, as everyone was observing with wonder, the real estate collapse had not flattened rents one bit.

Howard looked around at all the stuff that represented his last thirty years. “Bon voyage,” he said. He gave me a little hug.

The plane took off in frosty grime and floated down across water, from which the sun was rising in sheer pink and yellow flounces. It was a different time here—must that not mean that different things were happening? I’d brought my computer, but maybe I could actually just not turn it on, and the dreary growth of little obligations that overran my screen would just disappear; maybe the news, which—like a magic substance in a fairy tale—was producing perpetually increasing awfulness from rock-bottom bad, would just disappear.

Way back—oh, not all that long ago, actually, just a couple of years, but back before I’d gotten a glimpse of the gears and levers and pulleys that dredge the future up from the earth’s core to its surface—I was going to a lot of parties.

And at one of these parties there was a couple, Ray and Christa, who hung out with various people I sort of knew, or, anyhow, whose names I knew. We’d never had much of a conversation, just hey there, kind of thing, but I’d seen them at parties over the years and at that particular party they seemed to forget that we weren’t actually friends ourselves.

Ray and Christa had a lot of money, a serious quantity, and they were also both very good-looking, so they could live the way they felt like living. Sometimes they split up, and one of them, usually Ray, was with someone else for a while, always a splashy, public business that made their entourage scatter like flummoxed chickens, but inevitably they got back together, and afterwards, you couldn’t detect a scar.

Ray had a chummy arm around me and Christa was swaying to the music, which was almost drowned out by the din of voices in the metallic room, and smiling absently in my direction. I was a little taken aback that I was being, I guess, anointed, but it was up to them how well they knew you, and I could only assume that their cordiality meant either that something good had happened to me which was not yet perceptible to me but was already perceptible to them, or else that something good was about to happen to me.

So, we were talking, shouting, really, over the noise, and after a bit I realized that what they were saying meant that they now owned my painting Blue Hill.

They owned Blue Hill? I had given Blue Hill to Graham once, in a happy moment, and he must have sold it to them when he up and moved to Barcelona. Blue Hill is not a bad painting, in my opinion, it’s one of my best, still, the expression that I could feel taking charge of my face came and went without making trouble for anyone, thanks to the fact that, obviously, there were a lot of people in the room for Ray and Christa to be looking at, other than me.

How are you these days, they asked, and at this faint suggestion that they’d been monitoring me, a great wave of childish gratitude and relief washed over me, dissolving my dignity and leaving me stranded in self-pity.

Why did I keep going to these stupid parties? Night after night, parties, parties—was I hoping to meet someone? No one met people in person any longer—you couldn’t hear what they were saying. Except for the younger women, who had piercing, high voices and sounded like Donald Duck, from whom they had evidently learned to talk. When had that happened? An adaptation? You could certainly hear them.

It was getting on my nerves and making me feel old. I’m exhausted, I told Ray and Christa. I can’t sleep. I can’t take the winter. I’m sick of my day job at Howard’s photo studio, but on the other hand, Howard’s having some problems—last week there were three of us, and this week there are two, and I’m scared I’m going to be the next to go. And as I told them that I was frightened, that I was sick of the winter and my job, I understood how deeply, deeply sick of the winter and my job, how frightened, I really was.

Yeah, that’s terrible, they said. Well, why don’t you come stay with us? We’re taking off for our beach place on Wednesday. There’s plenty of room, and you can paint. We love your work. It’s a great place to work, everyone says so, really serene. The light is great, the vistas are great.

I’m having some trouble painting these days, I said, I’m not really, I don’t know.

Hey, everyone needs some downtime, they said; you’ll be inspired, everyone who visits is inspired. You won’t have to deal with anything. There’s a cook. You can lie around in the sun and recuperate. You can take donkey rides down into the town, or there are bicycles or the driver. What languages do you speak? Well, it doesn’t matter. You won’t need to speak any.

Naturally I assumed they’d forget all about their invitation, so I was startled, the day after the party, to get an email from Christa, asking when I could get away. One of their people would deal with the flights. I could stay as long as I liked, she said, and if I wanted to send heavy working materials on ahead, that would be fine. Lots of their guests did that. It could get cool at night, so I should bring something warm, and if I wanted to hike, I should bring boots, because snakes, as I knew, could be an issue, though insects were generally not. I would not need a visa these days, so not to worry about that, and not to worry about Wi-Fi—that was all set up.

I doubted that anybody else who visited them would not know exactly how to prepare, and yet there was Christa, informing me so tactfully of everything, like snakes and visas, that I’d need to know about, by pretending that of course I’d already have thought of those things. A week or so later, a messenger brought a plane ticket up the five flights of stairs to my little apartment, which was when it dawned on me that the good thing Ray and Christa had perceived happening to me was that they now owned one of my paintings, which meant, obviously, that it most likely was, or would soon be, worth acquiring.

My job at Howard’s studio expired, along with the studio itself, at the end of the following month, just in time to save Howard and me from my quitting right before I got on the plane. At least it was no problem to sublet my apartment, even at a little profit, to a guy who liked cats, because, as everyone was observing with wonder, the real estate collapse had not flattened rents one bit.

Howard looked around at all the stuff that represented his last thirty years. “Bon voyage,” he said. He gave me a little hug.

The plane took off in frosty grime and floated down across water, from which the sun was rising in sheer pink and yellow flounces. It was a different time here—must that not mean that different things were happening? I’d brought my computer, but maybe I could actually just not turn it on, and the dreary growth of little obligations that overran my screen would just disappear; maybe the news, which—like a magic substance in a fairy tale—was producing perpetually increasing awfulness from rock-bottom bad, would just disappear.

Recenzii

“Widely regarded as the nation’s most prestigious awards for short fiction.” —The Atlantic Monthly

Cuprins

Your Duck Is My Duck, by DEBORAH EISENBERG

Sugarcane, by DEREK PALACIO

The Summer People, by KELLY LINK

Leaving Maverley, by ALICE MUNRO

White Carnations, by POLLY ROSENWAIKE

Sail, by TASH AW

Anecdotes, by ANN BEATTIE

Lay My Head, by L. ANNETTE BINDER

He Knew, by DONALD ANTRIM

The Visitor, by ASAKO SERIZAWA

Where Do You Go? by SAMAR FARAH FITZGERALD

Aphrodisiac, by RUTH PRAWER JHABVALA

Two Opinions, by JOAN SILBER

They Find the Drowned, by MELINDA MOUSTAKIS

The Mexican, by GEORGE MCCORMICK

Tiger, by NALINI JONES

Pérou, by LILY TUCK

Sinkhole, by JAMIE QUATRO

The History of Girls, by AYŞE PAPATYA BUCAK

The Particles, by ANDREA BARRETT

Sugarcane, by DEREK PALACIO

The Summer People, by KELLY LINK

Leaving Maverley, by ALICE MUNRO

White Carnations, by POLLY ROSENWAIKE

Sail, by TASH AW

Anecdotes, by ANN BEATTIE

Lay My Head, by L. ANNETTE BINDER

He Knew, by DONALD ANTRIM

The Visitor, by ASAKO SERIZAWA

Where Do You Go? by SAMAR FARAH FITZGERALD

Aphrodisiac, by RUTH PRAWER JHABVALA

Two Opinions, by JOAN SILBER

They Find the Drowned, by MELINDA MOUSTAKIS

The Mexican, by GEORGE MCCORMICK

Tiger, by NALINI JONES

Pérou, by LILY TUCK

Sinkhole, by JAMIE QUATRO

The History of Girls, by AYŞE PAPATYA BUCAK

The Particles, by ANDREA BARRETT

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Under the direction of a new series editor, this edition features an exciting selection of the best stories of 2003 published in hundreds of literary magazines.

Under the direction of a new series editor, this edition features an exciting selection of the best stories of 2003 published in hundreds of literary magazines.