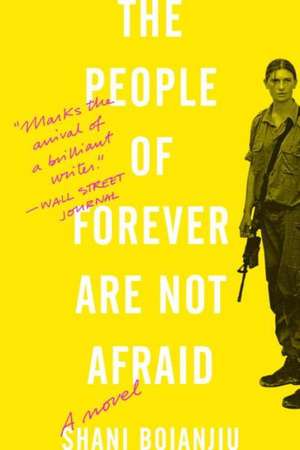

The People of Forever Are Not Afraid

Autor Shani Boianjiuen Limba Engleză Paperback – 24 iun 2013

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

In a relentlessly energetic and arresting voice marked by humor and fierce intelligence, Shani Boianjiu creates an unforgettably intense world, capturing that unique time in a young woman's life when a single moment can change everything.

Now with Extra Libris material, including a reader’s guide and bonus content

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 100.39 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Hogarth – 24 iun 2013 | 111.99 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Vintage Publishing – 30 apr 2014 | 100.39 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 111.99 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.43€ • 22.25$ • 17.87£

21.43€ • 22.25$ • 17.87£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307955975

ISBN-10: 0307955974

Pagini: 354

Dimensiuni: 130 x 209 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Hogarth

ISBN-10: 0307955974

Pagini: 354

Dimensiuni: 130 x 209 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Hogarth

Extras

Other People's Children

History Is Almost Over

There is dust in this caravan of a classroom, and Mira the teacher's hair is fake orange and scorched at the tips. We are seniors now, seventeen, and we have almost finished all of Israeli history. We finished the history of the world in tenth grade. In our textbook, the pages already speak to us of 1982, just a few years before we were born, just a year before this town was built, when there were only pine trees and garbage hills here by the Lebanese border. The words of Mira the teacher, who is also Avishag's mother, almost touch the secret ones of all our parents in their drunken evenings.

History is almost over.

"There are going to be eight definitions in the Peace of the Galilee War quiz next Friday, and there is nothing we haven't covered. PLO, SAM, IAF, RPG children," Mira says. I am pretty sure I know all the terms, except for maybe RPG children. I am not as good with definitions that have real words in them. They scare me a little.

But I don't care about this quiz. I will almost swear; I don't care one bit.

I still have my sandwich waiting for me in my backpack. It has tomatoes and mayo and mustard and salt and nothing more. The best part is that my mother puts it inside a plastic bag and then she wraps it in blue napkins and it takes about two minutes to unwrap it. That way even if it is a day when I am not hungry I can wait for something. That's something, and I can keep from screaming.

It has been eight years since I discovered mustard-mayo-tomato.

I snap my fingers under my jaw. I roll my eyes. I grind my teeth. I have been doing these things since I was little, sitting in class. I can't do this for much longer. My teeth hurt.

Forty minutes till recess, but I can't keep sitting here, and I can't and I won't and I--

How They Make Airplanes

"PLO, SAM, IAF, RPG children," Mira the teacher says. "Who wants to practice reading some definitions out loud before the quiz?"

SAM is some sort of Syrian submarine. And IAF is the Israeli Air Force. I know what children are, and that RPG children were children who tried to shoot RPGs at our soldiers and ended up burning each other because they were uninformed, and children. But that might be a repetitive definition. Last time the bitch took off five points because she said I used the word "very" seven times in the same definition and that I used it in places where you can't really use "very."

She is looking at me, or at Avishag, who is sitting next to me, or at Lea, who is sitting next to her. She sighs. I think she needs to have very corrective eye surgery. Lea shoots a look right back, as if she is convinced Mira was looking at her. She always thinks everyone must be looking at her.

"Can you at least pretend to be writing this down, Yael?" Mira asks me and sits down behind her desk.

I pull my eyes away from Lea. I pick up the pen and write:

when are we going to stop thinking about things that don't matter and start thinking about things that do matter? fuck me raw

I have to go to the bathroom. Outside the classroom caravan there is the bathroom caravan. When I stand on top of the closed toilet and press my nose against the tiny window, I can see the end of the village and breathe the bleach they use to clean this forsaken window till I am dizzy. I can see houses and gardens and mothers of babies on benches, all scattered like Lego parts abandoned by a giant child at the side of the cement road leading to the brown mountains sleeping ahead. Right outside the gates of the school, I see a young man. He is wearing a brown shirt and his skin is light brown and he could almost disappear on this mountain if it weren't for his green eyes, two leaves in the middle of this nothing.

It's Dan. My Dan. Avishag's brother.

I am almost sure.

When I come back to class from the bathroom, I see that someone has written in the old, fat notebook, right below my question. Avishag and I have been writing in notebooks to each other since second grade. For a while we kept the stories we wrote with Lea when we all played Exquisite Corpse in a notebook too, but by seventh grade Lea had stopped playing with us, or with any of her old friends. She started collecting girls, pets, instead, to do as she said. Avishag said the two of us should still write in a notebook, even though two people can't play Exquisite Corpse. She said the notebooks are something we can keep around longer than notes on loose leaf and that this way, when we're eighteen, we'll be able to look back and remember all the people who loved us back then, back when we were young. And that way she'd also have a place for her sketches, and she could make sure I saw each of them. Also, she said when we were fourteen, we could have the word "fuck" in each sentence if we wanted to and not get caught, and we do want to, and we should, and we must. It is a rule.

fuck me rawer

Recently, it is like Avishag doesn't even exist. Everything I say she says a little louder. Then she grows quiet. She plays with the golden necklace on her dark chest. She fine-tunes her bra strap. She watches her hair grow longer and she grows silent. I guess I am growing in the same ways.

But the thing is, for the first time in the history of the world, someone other than Avishag wrote in the notebook while I was gone.

I am almost sure. There is another odd line, and no "fuck."

i am alone all the time. even right now, I am alone

I close the notebook.

I want to ask Avishag if her brother Dan came into the classroom when I was gone, but I don't. Avishag and Dan's mother, Mira, is special among mothers because she is a teacher. She is a teacher because she had to come and be a teacher in a village instead of in Jerusalem. Avishag's dad left them, so they didn't have enough money to stay in Jerusalem. My mother works in the company in the village that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that can make airplanes. Lea's mother works in the company in the village that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that can make airplanes. I am alone all the time.

I have this idea.

I am going to have a party even if it kills me, and I still don't know where the party is going to be, and I can't know, and I won't know anything more in the next twenty minutes because I am in class, but so help me God, Dan is going to come to this party. He will if I call to invite him, that's just manners, and it is this brilliant idea I just thought of, out of nowhere, a party, and if one more person tells me that sometimes it is Ok to be alone, I will scream and it is going to be awkward.

"Peace," I say and get up from my desk. I pick up my backpack. When Avishag gets up, her chair scratches the linoleum floor and makes Mira's lips pucker as if she just ate a whole lemon from the tree of the Levy family.

"There are still twenty minutes left in this class," she says. She might think we'll stay, but we leave.

"Fuck it. Peace," Avishag says. This is rare. Avishag hates it when swear words are said out loud. She only loves them written, so this is rare. Four boys get up as well. In fourth grade one of them ate a whole lemon from the Levy family's tree on a dare, but nothing happened after that.

You Can't Talk to Anyone

Avishag and I are walking up on the main dirt road leading up from the school. When I open my mouth, I can taste specks of the footsteps of our classmates before us and our own from the day before. I can barely speak there is so much in my mouth.

"I'm, like, dying. We have to have a party tonight. We have to make some calls," I say.

"Noam and Emuna told me that Yochai told them that his brother heard from Lea's sister Sarit where to get reception," Avishag says. Her black eyes squint.

All the cellular phones in the town don't work right now. At first there was no reception only at school. Then last Wednesday we didn't have reception even after we jumped behind the wooden gate and cut math. Avishag got two bars for, like, ten seconds, but it wasn't enough to call anyone. Then it became one bar and didn't change back.

We already walked to the grocery store, but there was no reception there, so we bought a pack of Marlboros and some gummy bears and walked to the ATM, but there was no reception there, so we walked to the small park, but there was no reception there, and someone had puked on the only swing big enough for two, so we didn't even stay, and then there was no other place in town we could go.

"It is actually not Noam or Yochai who told me," Avishag says. "Dan told me. He is speaking to me again. Or at least, enough to say that there is reception by the cellular tower."

I don't look at Avishag after she says that. I want to ask her if Dan came in and wrote in the notebook, but I know better.

The cellular tower. Of course. Sometimes I think that if it weren't for people like Dan the whole village would die, we're that stupid.

What Is Love

In my whole entire life I only decided to love one boy, Avishag's brother, Dan. I have had the same boyfriend, Moshe, since I was twelve, but that's not really fair because I didn't really get to decide to love him. He was a family friend who threw apples at me, so I didn't really have a choice. Two weeks ago we broke up. We also broke up nine weeks ago. He has been in the army for about six months now, anyway. Dan is already done with all of that.

Dan used to have this test. That's why I decided to love him. It would drive him fucking crazy, this test.

Right at the end of Jerusalem Street, our town has a view. It has a view of the entire world and its sister. Really, it does. Standing there on top of that tiny hill you can see four mountains bursting with forever-green Mediterranean forest. You can see blankets of red anemones and pillows of purple anemones and circles of yellow daisies. And little caves protected by willows, and well, it hurts almost to look at it. Like seeing other people's children on the other side of the street.

And there are benches, of course, right there at the end of Jerusalem Street, and you would think you could sit and look out at this view, except you can't. Because if you did, your back would be to the view, and you would be staring at house number twenty-four on Jerusalem Street, and all you would notice are the underwear hanging to dry and an orphaned dog leash on the yellow grass and the recycling bin out on the porch.

And he would bring people there, Dan, and he would ask, what is wrong with this picture what is wrong what is wrong, and no one could tell him and he would grow mad, grow loud, and he would say that if it weren't for people like him the whole village would fucking die, we're that stupid. He can be arrogant. And then the person he would bring there from the town, his classmate, his mother's friend, his sister, his younger sister, would sit there staring at the yellow grass of house twenty-four for a while and say, "You said you wanted to hang out. I don't understand." But I understood.

In seventh grade, after I left Avishag's house, Dan jumped at me from behind an olive tree. Above him there were imported sycamore trees and birds, and the birds were invisible but swished around so quickly in circles they made spots of light dance around him, like in a discotheque. He moved one step closer. And then one more. He was so close I could see two eyelashes that had fallen off and were resting on his left cheek. I looked down, embarrassed, and noticed that his feet were bare and long. I snapped my fingers under my neck, nervous. He was so tall, just like Avishag. Or maybe I was short.

"Do you want to hang out?" he asked.

When I sat on that bench I just felt tired for a second. I turned my back around again and again to look away, so Dan wouldn't see how excited I was, so I would have something else beautiful to think about. And then it hit me.

"So a person comes and he has two benches and they tell him, 'Use cement and plant these benches in the ground,' and he, well," I said. I just wanted to have something to say, but Dan's green eyes were beaming, and his thick eyebrows were going up and down.

After that we sat there for a while on the ground, looking at the red blankets and caves ahead, and I told him all my secrets. That night I think I loved him a bit, but I don't know if it was true love because I only loved him because he loved me, or something I said. You could see that he did by the way he was rocking back and forth and also because when I showed him the notebook he promised he would write in it one day, something fucking smart.

I never spoke to him again after that night. Two months later he told Avishag one of my secrets. Two years after that he went into the army, and when he got back, instead of working in the company in the village that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that make airplanes, or going to professional school so he could later be paid more to work in the company in the town that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that make airplanes, he just stayed home and drew pictures of military boots. I know because my sister went there last week to play with his littlest sister, and when she came back she said there were sketches of boots and boots and boots. The entire kitchen wall was black with them, and heavy.

History Is Almost Over

There is dust in this caravan of a classroom, and Mira the teacher's hair is fake orange and scorched at the tips. We are seniors now, seventeen, and we have almost finished all of Israeli history. We finished the history of the world in tenth grade. In our textbook, the pages already speak to us of 1982, just a few years before we were born, just a year before this town was built, when there were only pine trees and garbage hills here by the Lebanese border. The words of Mira the teacher, who is also Avishag's mother, almost touch the secret ones of all our parents in their drunken evenings.

History is almost over.

"There are going to be eight definitions in the Peace of the Galilee War quiz next Friday, and there is nothing we haven't covered. PLO, SAM, IAF, RPG children," Mira says. I am pretty sure I know all the terms, except for maybe RPG children. I am not as good with definitions that have real words in them. They scare me a little.

But I don't care about this quiz. I will almost swear; I don't care one bit.

I still have my sandwich waiting for me in my backpack. It has tomatoes and mayo and mustard and salt and nothing more. The best part is that my mother puts it inside a plastic bag and then she wraps it in blue napkins and it takes about two minutes to unwrap it. That way even if it is a day when I am not hungry I can wait for something. That's something, and I can keep from screaming.

It has been eight years since I discovered mustard-mayo-tomato.

I snap my fingers under my jaw. I roll my eyes. I grind my teeth. I have been doing these things since I was little, sitting in class. I can't do this for much longer. My teeth hurt.

Forty minutes till recess, but I can't keep sitting here, and I can't and I won't and I--

How They Make Airplanes

"PLO, SAM, IAF, RPG children," Mira the teacher says. "Who wants to practice reading some definitions out loud before the quiz?"

SAM is some sort of Syrian submarine. And IAF is the Israeli Air Force. I know what children are, and that RPG children were children who tried to shoot RPGs at our soldiers and ended up burning each other because they were uninformed, and children. But that might be a repetitive definition. Last time the bitch took off five points because she said I used the word "very" seven times in the same definition and that I used it in places where you can't really use "very."

She is looking at me, or at Avishag, who is sitting next to me, or at Lea, who is sitting next to her. She sighs. I think she needs to have very corrective eye surgery. Lea shoots a look right back, as if she is convinced Mira was looking at her. She always thinks everyone must be looking at her.

"Can you at least pretend to be writing this down, Yael?" Mira asks me and sits down behind her desk.

I pull my eyes away from Lea. I pick up the pen and write:

when are we going to stop thinking about things that don't matter and start thinking about things that do matter? fuck me raw

I have to go to the bathroom. Outside the classroom caravan there is the bathroom caravan. When I stand on top of the closed toilet and press my nose against the tiny window, I can see the end of the village and breathe the bleach they use to clean this forsaken window till I am dizzy. I can see houses and gardens and mothers of babies on benches, all scattered like Lego parts abandoned by a giant child at the side of the cement road leading to the brown mountains sleeping ahead. Right outside the gates of the school, I see a young man. He is wearing a brown shirt and his skin is light brown and he could almost disappear on this mountain if it weren't for his green eyes, two leaves in the middle of this nothing.

It's Dan. My Dan. Avishag's brother.

I am almost sure.

When I come back to class from the bathroom, I see that someone has written in the old, fat notebook, right below my question. Avishag and I have been writing in notebooks to each other since second grade. For a while we kept the stories we wrote with Lea when we all played Exquisite Corpse in a notebook too, but by seventh grade Lea had stopped playing with us, or with any of her old friends. She started collecting girls, pets, instead, to do as she said. Avishag said the two of us should still write in a notebook, even though two people can't play Exquisite Corpse. She said the notebooks are something we can keep around longer than notes on loose leaf and that this way, when we're eighteen, we'll be able to look back and remember all the people who loved us back then, back when we were young. And that way she'd also have a place for her sketches, and she could make sure I saw each of them. Also, she said when we were fourteen, we could have the word "fuck" in each sentence if we wanted to and not get caught, and we do want to, and we should, and we must. It is a rule.

fuck me rawer

Recently, it is like Avishag doesn't even exist. Everything I say she says a little louder. Then she grows quiet. She plays with the golden necklace on her dark chest. She fine-tunes her bra strap. She watches her hair grow longer and she grows silent. I guess I am growing in the same ways.

But the thing is, for the first time in the history of the world, someone other than Avishag wrote in the notebook while I was gone.

I am almost sure. There is another odd line, and no "fuck."

i am alone all the time. even right now, I am alone

I close the notebook.

I want to ask Avishag if her brother Dan came into the classroom when I was gone, but I don't. Avishag and Dan's mother, Mira, is special among mothers because she is a teacher. She is a teacher because she had to come and be a teacher in a village instead of in Jerusalem. Avishag's dad left them, so they didn't have enough money to stay in Jerusalem. My mother works in the company in the village that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that can make airplanes. Lea's mother works in the company in the village that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that can make airplanes. I am alone all the time.

I have this idea.

I am going to have a party even if it kills me, and I still don't know where the party is going to be, and I can't know, and I won't know anything more in the next twenty minutes because I am in class, but so help me God, Dan is going to come to this party. He will if I call to invite him, that's just manners, and it is this brilliant idea I just thought of, out of nowhere, a party, and if one more person tells me that sometimes it is Ok to be alone, I will scream and it is going to be awkward.

"Peace," I say and get up from my desk. I pick up my backpack. When Avishag gets up, her chair scratches the linoleum floor and makes Mira's lips pucker as if she just ate a whole lemon from the tree of the Levy family.

"There are still twenty minutes left in this class," she says. She might think we'll stay, but we leave.

"Fuck it. Peace," Avishag says. This is rare. Avishag hates it when swear words are said out loud. She only loves them written, so this is rare. Four boys get up as well. In fourth grade one of them ate a whole lemon from the Levy family's tree on a dare, but nothing happened after that.

You Can't Talk to Anyone

Avishag and I are walking up on the main dirt road leading up from the school. When I open my mouth, I can taste specks of the footsteps of our classmates before us and our own from the day before. I can barely speak there is so much in my mouth.

"I'm, like, dying. We have to have a party tonight. We have to make some calls," I say.

"Noam and Emuna told me that Yochai told them that his brother heard from Lea's sister Sarit where to get reception," Avishag says. Her black eyes squint.

All the cellular phones in the town don't work right now. At first there was no reception only at school. Then last Wednesday we didn't have reception even after we jumped behind the wooden gate and cut math. Avishag got two bars for, like, ten seconds, but it wasn't enough to call anyone. Then it became one bar and didn't change back.

We already walked to the grocery store, but there was no reception there, so we bought a pack of Marlboros and some gummy bears and walked to the ATM, but there was no reception there, so we walked to the small park, but there was no reception there, and someone had puked on the only swing big enough for two, so we didn't even stay, and then there was no other place in town we could go.

"It is actually not Noam or Yochai who told me," Avishag says. "Dan told me. He is speaking to me again. Or at least, enough to say that there is reception by the cellular tower."

I don't look at Avishag after she says that. I want to ask her if Dan came in and wrote in the notebook, but I know better.

The cellular tower. Of course. Sometimes I think that if it weren't for people like Dan the whole village would die, we're that stupid.

What Is Love

In my whole entire life I only decided to love one boy, Avishag's brother, Dan. I have had the same boyfriend, Moshe, since I was twelve, but that's not really fair because I didn't really get to decide to love him. He was a family friend who threw apples at me, so I didn't really have a choice. Two weeks ago we broke up. We also broke up nine weeks ago. He has been in the army for about six months now, anyway. Dan is already done with all of that.

Dan used to have this test. That's why I decided to love him. It would drive him fucking crazy, this test.

Right at the end of Jerusalem Street, our town has a view. It has a view of the entire world and its sister. Really, it does. Standing there on top of that tiny hill you can see four mountains bursting with forever-green Mediterranean forest. You can see blankets of red anemones and pillows of purple anemones and circles of yellow daisies. And little caves protected by willows, and well, it hurts almost to look at it. Like seeing other people's children on the other side of the street.

And there are benches, of course, right there at the end of Jerusalem Street, and you would think you could sit and look out at this view, except you can't. Because if you did, your back would be to the view, and you would be staring at house number twenty-four on Jerusalem Street, and all you would notice are the underwear hanging to dry and an orphaned dog leash on the yellow grass and the recycling bin out on the porch.

And he would bring people there, Dan, and he would ask, what is wrong with this picture what is wrong what is wrong, and no one could tell him and he would grow mad, grow loud, and he would say that if it weren't for people like him the whole village would fucking die, we're that stupid. He can be arrogant. And then the person he would bring there from the town, his classmate, his mother's friend, his sister, his younger sister, would sit there staring at the yellow grass of house twenty-four for a while and say, "You said you wanted to hang out. I don't understand." But I understood.

In seventh grade, after I left Avishag's house, Dan jumped at me from behind an olive tree. Above him there were imported sycamore trees and birds, and the birds were invisible but swished around so quickly in circles they made spots of light dance around him, like in a discotheque. He moved one step closer. And then one more. He was so close I could see two eyelashes that had fallen off and were resting on his left cheek. I looked down, embarrassed, and noticed that his feet were bare and long. I snapped my fingers under my neck, nervous. He was so tall, just like Avishag. Or maybe I was short.

"Do you want to hang out?" he asked.

When I sat on that bench I just felt tired for a second. I turned my back around again and again to look away, so Dan wouldn't see how excited I was, so I would have something else beautiful to think about. And then it hit me.

"So a person comes and he has two benches and they tell him, 'Use cement and plant these benches in the ground,' and he, well," I said. I just wanted to have something to say, but Dan's green eyes were beaming, and his thick eyebrows were going up and down.

After that we sat there for a while on the ground, looking at the red blankets and caves ahead, and I told him all my secrets. That night I think I loved him a bit, but I don't know if it was true love because I only loved him because he loved me, or something I said. You could see that he did by the way he was rocking back and forth and also because when I showed him the notebook he promised he would write in it one day, something fucking smart.

I never spoke to him again after that night. Two months later he told Avishag one of my secrets. Two years after that he went into the army, and when he got back, instead of working in the company in the village that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that make airplanes, or going to professional school so he could later be paid more to work in the company in the town that makes parts that go into machines that help make machines that make airplanes, he just stayed home and drew pictures of military boots. I know because my sister went there last week to play with his littlest sister, and when she came back she said there were sketches of boots and boots and boots. The entire kitchen wall was black with them, and heavy.

Recenzii

A 2013 Sami Rohr Prize Finalist

Longlisted for the Women's Prize for Fiction

A Wall Street Journal Best Fiction Pick of 2012

“Remarkable…Part of this impressive book’s power is that it manages to re-create and rupture that numbness, war’s tedium and the damage it does to memory, intimacy, thought and affection. At a time when so many of America’s best writers seem to be in retreat from realism, championing a return to genre fiction (zombies and ghosts, comic-book characters and thrillers), Boianjiu’s bracing honesty is tonic. It’s a tribute to Boianjiu’s artistry and humanity that she portrays those on both sides of the barbed wire as loved and feared. The People of Forever Are Not Afraid is a fierce and beautiful portrait of the damage done by war.”

—The Washington Post

"A dark, riveting window into the mind-state of Israel's younger generation, The People of Forever Are Not Afraid marks the arrival of a brilliant writer."

—Wall Street Journal

“With its blend of brutal hilarity and heart-stopping anguish, this is a brilliant debut novel.”

—The Boston Globe

“[Boianjiu’s] voice is distinct. It’s confident, raw, amusing — a lot like her women.”

—The New York Times

“Stunning…[a] beautifully rendered account of the absurdities and pathos inherent to everyday life in Israel.”

—Los Angeles Review of Books

“Boianjiu’s searing debut…draws from the author’s own experiences to render the absurdities of life and love on the precipice of violence.” —Vogue

“In her riveting debut novel, 25-year-old Shani Boianjiu gives a rare insider glimpse at what it’s like to be a girl coming of age in the famously fierce Israeli Defense Forces.” —Marie Claire

“In this Bildungsroman, life in the army initiates a metamorphosis from girl to woman…Boianjiu’s depiction of…the psyches of these young women is fascinating… The prose [reads] alternately like a nightmare and a dream, but this feverish indecision is what gives it its power.”

—The Economist

“This powerful novel follows three friends as they come of age in a village ߝ and then are enlisted into the Israeli Defense forces.”

—O, The Oprah Magazine

“That one debut novel to get excited about.”

—New York Magazine

“Must-read.”

—Harper’s Bazaar

“Boianjiu builds a deeply engaging narrative...and shows considerable range, creating surreal, absurd dilemmas for her characters...a promising start to Boianjiu’s career”

—Jewish Book Council

“Eye-opening and brutally honest...In this gripping debut, [Boianjiu] weaves together the familiar coming-of-age milestones such as sexual initiation, the fierce bonds of friendship and the need for independence with the shocking realities of military life—even beyond the battlefield.”

—Bookpage

“[An] elegantly written debut novel…25-year-old Boianjiu, drawing on her own years with the IDF, has written the story of a people’s resignation to living in a world that’s been strange for so long, they can no longer remember how strange it is.”

—The Forward

“An impressive debut…”

—New York Post

“The extraordinarily gifted Shani Boianjiu has published a first novel that is tense and taut as a thriller yet romantic and psychologically astute….. Boianjiu writes with clarity about atrocity and the absurdity of endless war, but it’s her tender acceptance of human frailty that ultimately makes this novel so engrossing.”

—More Magazine

“Boianjiu is clearly a gifted stylist and her first novel easily establishes her as a writer to watch.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“[A] tour de force…Powerfully direct…wonderfully vivid…more than just another promising debut from a talented young writer, [The People of Forever are not Afraid] warrants our full attention.”—Malibu Magazine

“The much-anticipated debut novel from 25-year-old Shani Boianjiu zigzags between the stories of three high-school friends, Yael, Avishag, and Lea, as they leave their small village on the Lebanese border to take up posts in the Israeli army… glimmers of humor and insight flash brightly in what is a brutally dark novel."

—The Daily Beast

“The People of Forever Are Not Afraid provides a fine flavor of what Israeli military life is like for young women — no mean feat — and many of the episodes are engaging and revealing. Read it for that flavor and those stories.”

—The Washington Independent Review of Books

“The novel resonates with considerable power…The People of Forever avoids melodrama; it is a novel of nuance and smart anti-climax…This isn't the constantly detonating Israel of American newspaper headlines. Actually, the country portrayed is a much more interesting and harrowing place. Its citizens and soldiers, we see, live in quiet expectation of calamity.”

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“It is incredibly rare and spectacular to find an author who possesses the literary talent to transport us so completely and persuasively to an utterly foreign realm. First time novelist, 24-year-old Shani Boianjiu, has performed such a feat in The People of Forever Are Not Afraid (Hogarth/Crown, $24), her disturbing and provocative new book about the traumatic experiences of three young Israeli girls serving in the Israeli Defense Forces.”

—The Jewish Journal

"In her complex, gritty first novel, Boianjiu portrays young women drafted into the Israeli army as they come of age. This is a great choice for literary fiction readers who can appreciate a thoroughly distinctive narrative voice.”

—Library Journal, starred review

"Shani Boianjiu has found a way to expose the effects of war and national doctrine on the lives of young Israelis. So her subject is serious, but lest I make her work sound in any way heavy let me point out how funny she is, how disarming and full of life. Even when she is writing about death, Boianjiu is more full of life than any young writer I've come across in a long time."

—Nicole Krauss, author of Great House and The History of Love

“[An] excellent debut novel…like Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? meets…The Things They Carried. Irreverent, sometimes touching and often deeply weird, we fell in love with Boianjiu’s voice from the first page. Bottom line? It sucked us in and carried us off at gunpoint.”

—Flavorwire.com

“This haunting coming-of-age story skillfully portrays the individual side of a war not often spoke of, much less written about. Destined to be an award-winner, this novel gives the reader a unique perspective of war and the devastation experienced by those fighting it.”

—SheKnows.com

“The People of Forever Are Not Afraid is... carefully wrought, consciously structured, creatively imagined.”

—The New Republic

"[An] impressive debut.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Readers will embrace the complexity of the writing.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Boianjiu’s debut novel chronicles the gritty, restless experiences of three young women during their compulsory service in the Israeli Defense Forces…The bold, matter-of-fact narrative…[mirrors] the complexity of a landscape in perpetual transition.”

—Booklist

“The term ‘a distinct new voice in literature” had became a cliché long before Shani Boianjiu was born, but there is no better way to describe her unique piercing tone. Reading it feels like having your heart sawn in to two by a very dull knife. The People of Forever are Not Afraid is one of those rare books that truly make you want to cry but at the same time doesn’t allow you to.”

—Etgar Keret, author of The Nimrod Flipout

“This is big literature ߝ the realism that nests inside the word surrealism.”

—Rivka Galchen, author of Atmospheric Disturbances

“If anyone ever tells you the novel is dead, don't say anything, just give them this book. Shani Boianjiu is an enormous new talent. This is one of the boldest debuts I can think of---it reads like it was written in bullets, tear gas, road flares and love. I demand another book from her, immediately."

—Alexander Chee, author of Edinburgh

“I was hooked on Shani Boianjiu's remarkable voice from the first sentence of this book. It's urgent, funny, horrifying, fresh, the kind of thing I've been dying to read for ages.”

—Miriam Toews, author of Irma Voth and A Complicated Kindness

“Boianjiu is a writer who should be talked about for literary reasons, not the least of which is that her stories refuse to submit to moral clichés.”

—The Times of Israel

Longlisted for the Women's Prize for Fiction

A Wall Street Journal Best Fiction Pick of 2012

“Remarkable…Part of this impressive book’s power is that it manages to re-create and rupture that numbness, war’s tedium and the damage it does to memory, intimacy, thought and affection. At a time when so many of America’s best writers seem to be in retreat from realism, championing a return to genre fiction (zombies and ghosts, comic-book characters and thrillers), Boianjiu’s bracing honesty is tonic. It’s a tribute to Boianjiu’s artistry and humanity that she portrays those on both sides of the barbed wire as loved and feared. The People of Forever Are Not Afraid is a fierce and beautiful portrait of the damage done by war.”

—The Washington Post

"A dark, riveting window into the mind-state of Israel's younger generation, The People of Forever Are Not Afraid marks the arrival of a brilliant writer."

—Wall Street Journal

“With its blend of brutal hilarity and heart-stopping anguish, this is a brilliant debut novel.”

—The Boston Globe

“[Boianjiu’s] voice is distinct. It’s confident, raw, amusing — a lot like her women.”

—The New York Times

“Stunning…[a] beautifully rendered account of the absurdities and pathos inherent to everyday life in Israel.”

—Los Angeles Review of Books

“Boianjiu’s searing debut…draws from the author’s own experiences to render the absurdities of life and love on the precipice of violence.” —Vogue

“In her riveting debut novel, 25-year-old Shani Boianjiu gives a rare insider glimpse at what it’s like to be a girl coming of age in the famously fierce Israeli Defense Forces.” —Marie Claire

“In this Bildungsroman, life in the army initiates a metamorphosis from girl to woman…Boianjiu’s depiction of…the psyches of these young women is fascinating… The prose [reads] alternately like a nightmare and a dream, but this feverish indecision is what gives it its power.”

—The Economist

“This powerful novel follows three friends as they come of age in a village ߝ and then are enlisted into the Israeli Defense forces.”

—O, The Oprah Magazine

“That one debut novel to get excited about.”

—New York Magazine

“Must-read.”

—Harper’s Bazaar

“Boianjiu builds a deeply engaging narrative...and shows considerable range, creating surreal, absurd dilemmas for her characters...a promising start to Boianjiu’s career”

—Jewish Book Council

“Eye-opening and brutally honest...In this gripping debut, [Boianjiu] weaves together the familiar coming-of-age milestones such as sexual initiation, the fierce bonds of friendship and the need for independence with the shocking realities of military life—even beyond the battlefield.”

—Bookpage

“[An] elegantly written debut novel…25-year-old Boianjiu, drawing on her own years with the IDF, has written the story of a people’s resignation to living in a world that’s been strange for so long, they can no longer remember how strange it is.”

—The Forward

“An impressive debut…”

—New York Post

“The extraordinarily gifted Shani Boianjiu has published a first novel that is tense and taut as a thriller yet romantic and psychologically astute….. Boianjiu writes with clarity about atrocity and the absurdity of endless war, but it’s her tender acceptance of human frailty that ultimately makes this novel so engrossing.”

—More Magazine

“Boianjiu is clearly a gifted stylist and her first novel easily establishes her as a writer to watch.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“[A] tour de force…Powerfully direct…wonderfully vivid…more than just another promising debut from a talented young writer, [The People of Forever are not Afraid] warrants our full attention.”—Malibu Magazine

“The much-anticipated debut novel from 25-year-old Shani Boianjiu zigzags between the stories of three high-school friends, Yael, Avishag, and Lea, as they leave their small village on the Lebanese border to take up posts in the Israeli army… glimmers of humor and insight flash brightly in what is a brutally dark novel."

—The Daily Beast

“The People of Forever Are Not Afraid provides a fine flavor of what Israeli military life is like for young women — no mean feat — and many of the episodes are engaging and revealing. Read it for that flavor and those stories.”

—The Washington Independent Review of Books

“The novel resonates with considerable power…The People of Forever avoids melodrama; it is a novel of nuance and smart anti-climax…This isn't the constantly detonating Israel of American newspaper headlines. Actually, the country portrayed is a much more interesting and harrowing place. Its citizens and soldiers, we see, live in quiet expectation of calamity.”

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“It is incredibly rare and spectacular to find an author who possesses the literary talent to transport us so completely and persuasively to an utterly foreign realm. First time novelist, 24-year-old Shani Boianjiu, has performed such a feat in The People of Forever Are Not Afraid (Hogarth/Crown, $24), her disturbing and provocative new book about the traumatic experiences of three young Israeli girls serving in the Israeli Defense Forces.”

—The Jewish Journal

"In her complex, gritty first novel, Boianjiu portrays young women drafted into the Israeli army as they come of age. This is a great choice for literary fiction readers who can appreciate a thoroughly distinctive narrative voice.”

—Library Journal, starred review

"Shani Boianjiu has found a way to expose the effects of war and national doctrine on the lives of young Israelis. So her subject is serious, but lest I make her work sound in any way heavy let me point out how funny she is, how disarming and full of life. Even when she is writing about death, Boianjiu is more full of life than any young writer I've come across in a long time."

—Nicole Krauss, author of Great House and The History of Love

“[An] excellent debut novel…like Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? meets…The Things They Carried. Irreverent, sometimes touching and often deeply weird, we fell in love with Boianjiu’s voice from the first page. Bottom line? It sucked us in and carried us off at gunpoint.”

—Flavorwire.com

“This haunting coming-of-age story skillfully portrays the individual side of a war not often spoke of, much less written about. Destined to be an award-winner, this novel gives the reader a unique perspective of war and the devastation experienced by those fighting it.”

—SheKnows.com

“The People of Forever Are Not Afraid is... carefully wrought, consciously structured, creatively imagined.”

—The New Republic

"[An] impressive debut.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Readers will embrace the complexity of the writing.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Boianjiu’s debut novel chronicles the gritty, restless experiences of three young women during their compulsory service in the Israeli Defense Forces…The bold, matter-of-fact narrative…[mirrors] the complexity of a landscape in perpetual transition.”

—Booklist

“The term ‘a distinct new voice in literature” had became a cliché long before Shani Boianjiu was born, but there is no better way to describe her unique piercing tone. Reading it feels like having your heart sawn in to two by a very dull knife. The People of Forever are Not Afraid is one of those rare books that truly make you want to cry but at the same time doesn’t allow you to.”

—Etgar Keret, author of The Nimrod Flipout

“This is big literature ߝ the realism that nests inside the word surrealism.”

—Rivka Galchen, author of Atmospheric Disturbances

“If anyone ever tells you the novel is dead, don't say anything, just give them this book. Shani Boianjiu is an enormous new talent. This is one of the boldest debuts I can think of---it reads like it was written in bullets, tear gas, road flares and love. I demand another book from her, immediately."

—Alexander Chee, author of Edinburgh

“I was hooked on Shani Boianjiu's remarkable voice from the first sentence of this book. It's urgent, funny, horrifying, fresh, the kind of thing I've been dying to read for ages.”

—Miriam Toews, author of Irma Voth and A Complicated Kindness

“Boianjiu is a writer who should be talked about for literary reasons, not the least of which is that her stories refuse to submit to moral clichés.”

—The Times of Israel

Notă biografică

Shani Boianjiu was born in Jerusalem in 1987 and grew up in the Galilee. She served in the Israeli Defense Forces for two years. She graduated from Harvard in 2011. Her debut novel has been published or will soon be published in 23 countries. It has been longlisted for the UK’s Women’s Prize for Fiction and selected as one of the ten best fiction titles of 2012 by the Wall Street Journal. She is the youngest recipient ever of the National Book Foundation’s 5 under 35 award. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, The New Yorker, Zoetrope, Vice, the Wall Street Journal, The Globe and Mail, Dazed and Confused, the Guardian and NPR.Com. She lives in Israel.

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Longlisted for the Women's Prize for Fiction Yael, Avishag and Lea grow up together in a tiny, dusty village in Israel. Yael trains marksmen, Avishag stands guard watching refugees throw themselves at barbed-wire fences and Lea, posted at a checkpoint, imagines the stories behind the familiar faces that pass by her day after day.

Longlisted for the Women's Prize for Fiction Yael, Avishag and Lea grow up together in a tiny, dusty village in Israel. Yael trains marksmen, Avishag stands guard watching refugees throw themselves at barbed-wire fences and Lea, posted at a checkpoint, imagines the stories behind the familiar faces that pass by her day after day.

Premii

- Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction Nominee, 2013