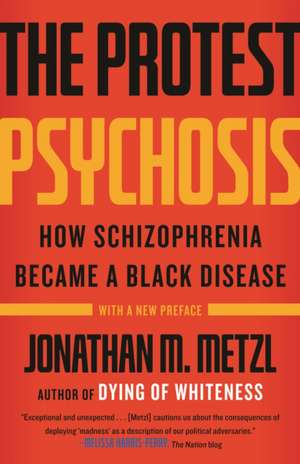

The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease

Autor Jonathan M. Metzlen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2011

The civil rights era is largely remembered as a time of sit-ins, boycotts, and riots. But a very different civil rights history evolved at the Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Ionia, Michigan. In The Protest Psychosis, psychiatrist and cultural critic Jonathan Metzl tells the shocking story of how schizophrenia became the diagnostic term overwhelmingly applied to African American protesters at Ionia—for political reasons as well as clinical ones. Expertly sifting through a vast array of cultural documents, Metzl shows how associations between schizophrenia and blackness emerged during the tumultuous decades of the 1960s and 1970s—and he provides a cautionary tale of how anxieties about race continue to impact doctor-patient interactions in our seemingly postracial America.

Preț: 149.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 224

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.51€ • 29.85$ • 23.59£

28.51€ • 29.85$ • 23.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Livrare express 28 februarie-06 martie pentru 26.99 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807001271

ISBN-10: 0807001279

Pagini: 246

Dimensiuni: 155 x 227 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807001279

Pagini: 246

Dimensiuni: 155 x 227 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Notă biografică

Jonathan M. Metzl is associate professor of psychiatry and women’s studies and director of the Culture, Health, and Medicine Program at the University of Michigan. A 2008 Guggenheim Fellowship recipient, Metzl has written extensively for medical, psychiatry, and popular publications. His books include Prozac on the Couch and Difference and Identity in Medicine. He lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Extras

Chapter 1: Homicidal

Cecil Peterson had no history with the police. Even on the day the white stranger insulted his mother, Peterson simply wanted to eat lunch. He sat in his usual seat at the counter of the diner on Woodward Street and ordered his usual BLT and coffee. Somehow he caught the stranger’s eye in the squinted way that begets immediate conflict between men. The stranger glared. Peterson was not one to walk away from confrontation, but he knew the implications of glaring back. One should not glare back at a white man. So he looked down. But the two men crossed paths again after Peterson paid his tab and walked outside. And then came the remark. And then came the fight.

Two white Detroit police officers happened to be passing by the diner that September day in 1966. They ran to the altercation and tried to separate the combatants. At that point, according to their formal report, Peterson turned on the officers and struck them “without provocation.” According to the report, Peterson knocked one officer down and “kicked him in the side.” A second police team arrived and assisted in apprehending the “agitated” Mr. Peterson. Medics took the first officers on the scene to the Wayne County Hospital emergency room. The ER physician’s report noted that both officers had “bruises,” though neither required treatment. The white stranger was not charged.

Peterson was twenty-nine, African American, and an unmarried father of four who worked the line at Cadillac Motor Company. He had not previously come to the attention of the state. He had not been diagnosed or treated for any physical or mental illness. Nor had he been held for crimes or misdemeanors. He had limited interactions with white people and preferred to stay close to home. But on that September day in 1966 his life changed along with his identity. He became a prisoner. And then he became a patient.

The Wayne County court convicted Mr. Peterson of two counts of “assault on a police officer causing injury requiring medical attention” and sent him to the Wayne County jail on a two- to ten-year sentence. After several weeks of incarceration, prison notes described Mr. Peterson as “extremely paranoid and potentially explosive,” screaming that “the white stranger” had “insulted my mother” and that his “civil rights” were being violated. The prison psychiatrist provided a diagnosis of “sociopathic personality disturbance with antisocial reaction,” and recommended seclusion, restraint, and continuous doses of Thorazine at 200 milligrams. Within six months, Mr. Peterson’s unprovoked outbursts became so severe that he earned the distinction of being a “problem inmate” who was “dangerous on the basis of his presenting a threat to the guards.” Soon thereafter, he began to ramble incoherently. One guard’s note explained that Mr. Peterson “occasionally grimaces, remains silent for long minutes, then looks up toward the ceiling with his eyes rolling in all directions.” A year into his incarceration, Mr. Peterson loudly accused the prison staff of “depriving him of women.” They observed him to be “hostile, suspicious, and increasingly annoyed” without any apparent provocation. He soon escalated, and the prison psychiatrist was called again. This time the psychiatrist recommended transferring Mr. Peterson to the notorious Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. The transfer sheet described Mr. Peterson as “HOMICIDAL.”

The drive to Ionia took four hours, much of which Mr. Peterson slept off in the back of the police car. But he stiffened when the vehicle pulled into the winding drive that led up to Ionia Hospital; and his attention reached the level of panic when the car doors opened onto the expansive, forty-onebuilding campus of bricks and chimneys and yards and fences and crazy people as far as the eye could see.

Dragged inside one of the largest of these buildings, Mr. Peterson shouted and struggled to get away. He said he was an “African warrior” and spoke gibberish, which he claimed to be his native African language. Then, in English, he loudly accused the guards of detaining him against his will. He claimed to be under attack by all white men.

Sylvan Cabrioto was not fazed. He had been the on-call physician at the Ionia receiving hospital since 1958, fully ten years before Cecil Peterson appeared in his examination room. A first-generation psychiatrist and secondgeneration American, Cabrioto was an authoritative, robust man of fifty-three who had a different bow tie for each day of the week. Treating the steady flow of burglars, peeping toms, pedophiles, and murderers who came through the Ionia doors gave Cabrioto a detached air of competence that undoubtedly resulted from having seen it all before. So he was not intimidated, at least not overtly, when Peterson appeared in the receiving hospital, or when the two prison guards drove off, or even when, after his handcuffs were taken off, Mr. Peterson “doubled up his fists” and gestured in a manner that was “irritable, disturbed, and sarcastic.”

It was, after all, a stance Cabrioto had seen in nearly every one of the growing number of “Negro” patients brought to the Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in the 1960s. One man heard the voice of Jesus telling him to come home. Another was certain that loved ones were trying to poison him. Another performed “mystic voodoo movements” while claiming an “eternal struggle against the white man.”

Like Peterson, most of the men came from “deteriorated neighborhoods” of Detroit. Most nonetheless held gainful employment. Like Peterson, each was convicted of a crime against person or property, ranging from larceny to murder to various forms of civil unrest. Few of the men had seen psychiatrists prior to their convictions, though this was not surprising since few psychiatrists resided in the urban sections of Detroit in the 1960s and 1970s. The men passed through various courts, prisons, and other state institutions. By the time they arrived at Ionia, they were nothing if not psychotic. Like Peterson, they hallucinated and ideated, or acted withdrawn, suspicious, paranoid, or combative. They argued, and fought, and resisted, and projected. And, according to Cabrioto and his colleagues, these actions were easily explained with a single diagnosis.

Cecil Peterson had no history with the police. Even on the day the white stranger insulted his mother, Peterson simply wanted to eat lunch. He sat in his usual seat at the counter of the diner on Woodward Street and ordered his usual BLT and coffee. Somehow he caught the stranger’s eye in the squinted way that begets immediate conflict between men. The stranger glared. Peterson was not one to walk away from confrontation, but he knew the implications of glaring back. One should not glare back at a white man. So he looked down. But the two men crossed paths again after Peterson paid his tab and walked outside. And then came the remark. And then came the fight.

Two white Detroit police officers happened to be passing by the diner that September day in 1966. They ran to the altercation and tried to separate the combatants. At that point, according to their formal report, Peterson turned on the officers and struck them “without provocation.” According to the report, Peterson knocked one officer down and “kicked him in the side.” A second police team arrived and assisted in apprehending the “agitated” Mr. Peterson. Medics took the first officers on the scene to the Wayne County Hospital emergency room. The ER physician’s report noted that both officers had “bruises,” though neither required treatment. The white stranger was not charged.

Peterson was twenty-nine, African American, and an unmarried father of four who worked the line at Cadillac Motor Company. He had not previously come to the attention of the state. He had not been diagnosed or treated for any physical or mental illness. Nor had he been held for crimes or misdemeanors. He had limited interactions with white people and preferred to stay close to home. But on that September day in 1966 his life changed along with his identity. He became a prisoner. And then he became a patient.

The Wayne County court convicted Mr. Peterson of two counts of “assault on a police officer causing injury requiring medical attention” and sent him to the Wayne County jail on a two- to ten-year sentence. After several weeks of incarceration, prison notes described Mr. Peterson as “extremely paranoid and potentially explosive,” screaming that “the white stranger” had “insulted my mother” and that his “civil rights” were being violated. The prison psychiatrist provided a diagnosis of “sociopathic personality disturbance with antisocial reaction,” and recommended seclusion, restraint, and continuous doses of Thorazine at 200 milligrams. Within six months, Mr. Peterson’s unprovoked outbursts became so severe that he earned the distinction of being a “problem inmate” who was “dangerous on the basis of his presenting a threat to the guards.” Soon thereafter, he began to ramble incoherently. One guard’s note explained that Mr. Peterson “occasionally grimaces, remains silent for long minutes, then looks up toward the ceiling with his eyes rolling in all directions.” A year into his incarceration, Mr. Peterson loudly accused the prison staff of “depriving him of women.” They observed him to be “hostile, suspicious, and increasingly annoyed” without any apparent provocation. He soon escalated, and the prison psychiatrist was called again. This time the psychiatrist recommended transferring Mr. Peterson to the notorious Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. The transfer sheet described Mr. Peterson as “HOMICIDAL.”

The drive to Ionia took four hours, much of which Mr. Peterson slept off in the back of the police car. But he stiffened when the vehicle pulled into the winding drive that led up to Ionia Hospital; and his attention reached the level of panic when the car doors opened onto the expansive, forty-onebuilding campus of bricks and chimneys and yards and fences and crazy people as far as the eye could see.

Dragged inside one of the largest of these buildings, Mr. Peterson shouted and struggled to get away. He said he was an “African warrior” and spoke gibberish, which he claimed to be his native African language. Then, in English, he loudly accused the guards of detaining him against his will. He claimed to be under attack by all white men.

Sylvan Cabrioto was not fazed. He had been the on-call physician at the Ionia receiving hospital since 1958, fully ten years before Cecil Peterson appeared in his examination room. A first-generation psychiatrist and secondgeneration American, Cabrioto was an authoritative, robust man of fifty-three who had a different bow tie for each day of the week. Treating the steady flow of burglars, peeping toms, pedophiles, and murderers who came through the Ionia doors gave Cabrioto a detached air of competence that undoubtedly resulted from having seen it all before. So he was not intimidated, at least not overtly, when Peterson appeared in the receiving hospital, or when the two prison guards drove off, or even when, after his handcuffs were taken off, Mr. Peterson “doubled up his fists” and gestured in a manner that was “irritable, disturbed, and sarcastic.”

It was, after all, a stance Cabrioto had seen in nearly every one of the growing number of “Negro” patients brought to the Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in the 1960s. One man heard the voice of Jesus telling him to come home. Another was certain that loved ones were trying to poison him. Another performed “mystic voodoo movements” while claiming an “eternal struggle against the white man.”

Like Peterson, most of the men came from “deteriorated neighborhoods” of Detroit. Most nonetheless held gainful employment. Like Peterson, each was convicted of a crime against person or property, ranging from larceny to murder to various forms of civil unrest. Few of the men had seen psychiatrists prior to their convictions, though this was not surprising since few psychiatrists resided in the urban sections of Detroit in the 1960s and 1970s. The men passed through various courts, prisons, and other state institutions. By the time they arrived at Ionia, they were nothing if not psychotic. Like Peterson, they hallucinated and ideated, or acted withdrawn, suspicious, paranoid, or combative. They argued, and fought, and resisted, and projected. And, according to Cabrioto and his colleagues, these actions were easily explained with a single diagnosis.

Cuprins

Preface The Protest Psychosis

Part I Ionia

1 Homicidal

2 Ionia

Part II Alice Wilson

3 She Tells Very Little about Her Behavior Yet Shows a Lot

4 Loosening Associations

5 Like a Family

Part III Octavius Greene

6 The Other Direction

7 Categories

8 Octavius Greene Had No Exit Interview

9 The Persistence of Memory

Part IV Caeser Williams

10 Too Close for Comfort

11 His Actions Are Determined Largely by His Emotions

12 Revisionist Mystery

13 A Racialized Disease

14 A Metaphor for Race

Part V Rasheed Karim

15 Turned Loose

16 Deinstitutionalization

17 Raised in a Slum Ghetto

18 Power, Knowledge, and Diagnostic Revision

19 Return of the Repressed

20 Rashomon

21 Something Else Instead

Part VI Remnants

22 Locked Away

23 Diversity

24 Inside

25 Remnants

26 Controllin’ the Planet

27 Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Part I Ionia

1 Homicidal

2 Ionia

Part II Alice Wilson

3 She Tells Very Little about Her Behavior Yet Shows a Lot

4 Loosening Associations

5 Like a Family

Part III Octavius Greene

6 The Other Direction

7 Categories

8 Octavius Greene Had No Exit Interview

9 The Persistence of Memory

Part IV Caeser Williams

10 Too Close for Comfort

11 His Actions Are Determined Largely by His Emotions

12 Revisionist Mystery

13 A Racialized Disease

14 A Metaphor for Race

Part V Rasheed Karim

15 Turned Loose

16 Deinstitutionalization

17 Raised in a Slum Ghetto

18 Power, Knowledge, and Diagnostic Revision

19 Return of the Repressed

20 Rashomon

21 Something Else Instead

Part VI Remnants

22 Locked Away

23 Diversity

24 Inside

25 Remnants

26 Controllin’ the Planet

27 Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Recenzii

“A terrific new book . . . exceptional and unexpected.”—Melissa Harris-Lacewell, The Nation blog

“A fascinating, penetrating book by one of medicine’s most exceptional young scholars.”—Delese Wear, JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association

“A stunning and disturbing book . . . [A] compelling cultural history that exposes postwar psychiatry’s racist character and its enduring legacy.”—Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

“Part reportage, part analysis, part theory . . . Metzl challenges readers to peel back the layered complexities of race and medicine.”—Felicia Pride, The Root

“[Metzl] make[s] a powerful case for the way schizophrenia was transformed into a racialized disease.”—Christopher Lane, Psychology Today

“Metzl addresses a long-standing diagnostic tension in psychiatry with insight, clarity, and informative historical detail.”—Health Affairs

“A fascinating, penetrating book by one of medicine’s most exceptional young scholars.”—Delese Wear, JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association

“A stunning and disturbing book . . . [A] compelling cultural history that exposes postwar psychiatry’s racist character and its enduring legacy.”—Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

“Part reportage, part analysis, part theory . . . Metzl challenges readers to peel back the layered complexities of race and medicine.”—Felicia Pride, The Root

“[Metzl] make[s] a powerful case for the way schizophrenia was transformed into a racialized disease.”—Christopher Lane, Psychology Today

“Metzl addresses a long-standing diagnostic tension in psychiatry with insight, clarity, and informative historical detail.”—Health Affairs