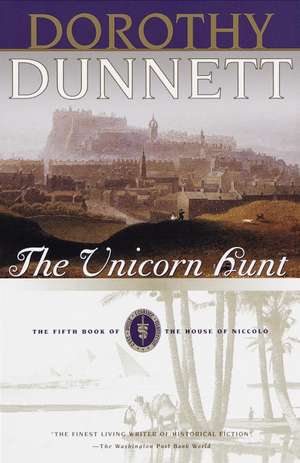

The Unicorn Hunt: The Fifth Book of the House of Niccolo: House of Niccolo, cartea 05

Autor Dorothy Dunnetten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 1999

Scotland, 1468: a nation at the edge of Europe, a civilization on the threshold of the Modern Age. Merchants, musicians, politicians, and pageantry fill the court of King James III. In its midst, Nicholas seeks to avenge his bride's claim that she carries the bastard of his archenemy, Simon St. Pol. When she flees before Nicholas can determine whether or not the rumored child is his own—or exists at all—Nicholas gives chase. So begins the deadly game of cat and mouse that will lead him from the infested cisterns of Cairo to the misted canals of Venice at carnival. Breathlessly paced, sparkling with wit. The Unicorn Hunt confirms Dorothy Dunnett as the genre's finest practitioner.

Toate formatele și edițiile

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 121.63 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Penguin Books – 23 noi 1994 | 121.63 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Vintage Publishing – 31 mai 1999 | 136.69 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 136.69 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 205

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.16€ • 28.43$ • 21.99£

26.16€ • 28.43$ • 21.99£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 19 aprilie-03 mai

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375704819

ISBN-10: 0375704817

Pagini: 688

Ilustrații: WITH 1 MAP AND GENEALOGY

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.56 kg

Ediția:VINTAGE BOOKS.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria House of Niccolo

ISBN-10: 0375704817

Pagini: 688

Ilustrații: WITH 1 MAP AND GENEALOGY

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.56 kg

Ediția:VINTAGE BOOKS.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria House of Niccolo

Notă biografică

Dorothy Dunnett was born in 1923 in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. Her time at Gillespie's High School for Girls overlapped with that of the novelist Muriel Spark. From 1940-1955, she worked for the Civil Service as a press officer. In 1946, she married Alastair Dunnett, later editor of The Scotsman.

Dunnett started writing in the late 1950s. Her first novel, The Game of Kings, was published in the United States in 1961, and in the United Kingdom the year after. She published 22 books in total, including the six-part Lymond Chronicles and the eight-part Niccolo Series, and co-authored another volume with her husband. Also an accomplished professional portrait painter, Dunnett exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy on many occasions and had portraits commissioned by a number of prominent public figures in Scotland.

She also led a busy life in public service, as a member of the Board of Trustees of the National Library of Scotland, a Trustee of the Scottish National War Memorial, and Director of the Edinburgh Book Festival. She served on numerous cultural committees, and was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. In 1992 she was awarded the Office of the British Empire for services to literature. She died on November 9, 2001, at the age of 78.

Dunnett started writing in the late 1950s. Her first novel, The Game of Kings, was published in the United States in 1961, and in the United Kingdom the year after. She published 22 books in total, including the six-part Lymond Chronicles and the eight-part Niccolo Series, and co-authored another volume with her husband. Also an accomplished professional portrait painter, Dunnett exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy on many occasions and had portraits commissioned by a number of prominent public figures in Scotland.

She also led a busy life in public service, as a member of the Board of Trustees of the National Library of Scotland, a Trustee of the Scottish National War Memorial, and Director of the Edinburgh Book Festival. She served on numerous cultural committees, and was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. In 1992 she was awarded the Office of the British Empire for services to literature. She died on November 9, 2001, at the age of 78.

Extras

Chapter 1

HENRY HAD OFTEN considered killing his grandfather; there was so much of him, and Henry disliked all of it.

Today the impulse came back quite strongly when, sticking his head upside down through the casement, he discovered the old man himself riding over the Kilmirren drawbridge. He could see his big hat, and the pennants, and the baggage-mules, and the men in half-armour to protect what was in all the boxes. They hadn't sounded their trumpets, and below in the courtyard people were scampering in every direction, attempting to help with the horses or even running away. No one liked Henry's grandfather.

Monseigneur Jourdain, the servants called him. It meant Chamberpot. His real name was Jordan de St Pol, vicomte de Rib?rac, and all this castle of Kilmirren was his, and the yards and trees and bothies that Henry looked down on, and the good farmlands and villages just beyond that Henry's father was supposed to look after. This was Monseigneur's Scottish castle, which he came to examine most years. The rest of the time he stayed in France.

Usually, everybody knew when to expect him. The message would come, and his father would curse, and then there would be a week when everyone was in a bad temper, trying to put things to rights. Then on the day, his father would stand in the doorway with Henry, his only son, at his side, and they would both welcome the old man as if they meant it. Fat Father Jordan was how his father referred to him.

Today, there had been no warning, which was terrible. No one knew better than Henry just how terrible it actually was. Henry set aside the hawk he had been feeding and, whirling down from his room, shoved open the door to his father's great chamber.

The bedcurtains were only half closed, so that he could see, with a pang of admiration and interest, what was happening behind them. Even now, in an emergency, he knew better than to interrupt. When it was finished (the signs were familiar) he said shrilly, 'Father! Father! Monseigneur is here!'

The first face to appear was the lady's. He had seen her before. She looked flushed, but didn't giggle like Beth or conceal herself with the sheet like the other one. This lady frowned at him, certainly, but bent and picked up her robe like an ordinary person. Like all his father's ladies, she was well set up as to the chest. Henry's friends all mentioned that, and the servants. They, too, were proud of his father. Henry used to wonder, now and then, if his mother had been flat in front like himself. She had died when Henry was three, but he didn't miss her. He didn't know why people thought he ought to miss her. He said, 'Father?' again, in case he had gone back to sleep.

'God's blood and bones,' said his father, and rolled over and pushed himself up.

Even angry, his father Simon was beautiful. Blond and blue-eyed and beautiful, and the finest jouster, the most splendid chevalier in the whole of Scotland. When Henry's grandfather was dead, Henry's father would be the lord of this castle and its grazing in the mid-west of Scotland. He would own his grandfather's castle in France, and his ships and his mills and his vineyards. His father would be Simon de St Pol, vicomte de Rib?rac, and Henry would be his sole son and heir, and a knight, with ladies to bounce with in bed. Flattish ladies, to be truthful, for preference.

God smote Henry then in the back. Henry was nervous of God. At once he saw, with relief, that it was the door, flung crashing open, which had pushed him aside. Then the relief promptly died, for in the entrance stood Jordan de St Pol, vicomte de Rib?rac, who was fatter than God and clean-shaven. Monseigneur Jourdain, his grandfather.

His grandfather said, 'Get rid of the bawd.'

'Bawd!' said the lady.

'I beg your pardon,' said his grandfather, looking at her. 'My lady, will you excuse us? And-Henry? I see your father is furthering your education?'

He didn't know what to say. 'Go!' muttered his father in no special direction.

'I should prefer to dress,' said the lady.

'Then pray do,' said Monseigneur. 'We see you don't mind an audience. I might even be more appreciative than a seven-year-old. Henry, I shall speak to you later.'

'Simon?' said the lady.

'I think you'd better dress in Henry's room,' said his father. 'Henry will show you the way. I apologise for the vicomte. Although he does not lodge in this wing, he seems to feel entitled to go where he pleases. Henry?'

Henry said, 'She can go somewhere else. I've got hawks in my room.'

'That, of course, must take precedence. So take her somewhere else, Henry,' said his grandfather. 'And then return to your room until I call for you.'

He took her somewhere else, but instead of returning to his room, he crept back to the half-open door, behind which his grandfather was haranguing his father. He could see them by holding the tapestry back just a little. If he were his father, he would knock him down. If his grandfather lifted a hand to his father he, Henry, would rush in and kill him. With the fire-tongs. With anything. He listened.

It was the old story. You would think that at last it didn't matter, whether the crops were sown a bit late or the hides not always cured to perfection or the smithwork patchy, or the peats left cut and lying too long. With the money from Madeira and the African voyage, they had enough to buy clothes with for years-even his silly aunt Lucia said so. And silver harness, and hawks, and jousting-armour. He had seen his father's new jousting-armour. You would think even his grandfather would be impressed, instead of threatening to get rid of Hugo and Steen, who had run the house and the land all the time his father was in Madeira and Flanders and Portugal. If Hugo and Steen were no good, why was his father being blamed for not staying in Flanders?

Flanders was a country far to the south, further south than England, across the Narrow Sea. Flanders was ruled by the Duke of Burgundy, the richest prince in the world. Henry had never been to Flanders.

'I cut short my visit to Bruges,' his grandfather said, 'because I bear a French title, and should be far from welcome at the Duke of Burgundy's wedding. But Kilmirren sends cargoes to Flanders. Why did you leave?'

Chamberpot Jordan. He occupied the only big chair like a throne. Everything about his father's father was big: his height, his width, the huge rolled hat on his head, the thick coat, the long robe, the solid boots. His hair was grey, and the whites of his eyes were yellow. He was old. He was over sixty years old and would live for ever, his father said, because he kept the accounts of the devil. His father had got out of bed and, without hurrying, had pulled on a gown without fastening it. His father had a narrow, ridged shape like Jesus. The old man said, 'You had a meeting with Nicholas.'

'Who?' said his father. He sat down on the platform-base of the bed and pulled on his slippers. Then he got up without an excuse and busied himself round the door of the privy. Henry felt hot. He knew who Nicholas was. Nicholas vander Poele, a wicked tradesman from Bruges who hated and cheated his father, if he could. But his father always won.

His father came back and sat down on the bed-base. 'Good. Are you comfortable?' said his grandfather. 'How unfortunate that we always seem to meet when your physique and intellect are both at their feeblest. I asked about your meeting with Nicholas. It was, as I remember, to determine the fate of two court cases. What was the outcome?'

His father laughed. The colour had come back to his skin. 'What do you think? He gave in. He promised not to take us to law over one ship, if we would agree not to contest possession of the other. We were lucky. He could have caused us some trouble.'

'So why didn't he?' the old man said.

His father had started to dress. Since Madeira, all his clothes were of silk. 'Who knows? Jellied in the brain from the African suns. He doesn't even claim us as kin any more. I wish he'd told me beforehand. I might have spared the mattress a little.'

The look that Henry feared had congealed upon his grandfather's face. His grandfather said, 'I am not sure what you mean.'

'I mean I got Gelis van Borselen under me,' his father said. 'Here, this summer. She made a little visit to Scotland six weeks before vander Poele married her. Now he's wedded my leavings. How's that?' He went on tying his points to his shirt. After a while, he looked up.

'Your late wife's sister,' said Grandfather Jordan reflectively. 'You seduced your sister by marriage, Gelis van Borselen of Veere, related to the rulers of Scotland and Burgundy? You raped her in advance of her wedding, because Nicholas vander Poele was her affianced husband?'

'Raped her!' his father said in mild protest. 'When did I ever need to do that? The girl was born with an itch, like her sister.'

The old man made a sound with his teeth, then resumed. 'In spite of which, she went back to Bruges. She did marry?'

'Of course she did!' his father said. 'He's settled half his fortune on her-half the gold he brought back from Africa. She'll be the richest woman in Flanders, and safe. He'd never know on the night. A well-trodden path, as they say, shows no prints.'

He smiled at the thought, and the smile broadened into a yawn. 'I've no complaints, and she won't soon forget it. She wanted to find out what her sister enjoyed, and she did.' He stopped smiling and flung up an arm. 'Damn you!' he exclaimed.

It was so quick, the movement of his grandfather's wrist, the pomander striking its target, the crash as the pierced silver ball fell to the floor, that Henry had no time to move. He heard his father cry out and saw the punch-mark on his brow where the skin began to turn bluish-red. Then his father roared, 'Damn you!' again.

It was why Henry was there, to protect him. He had his fists; he could kick. He jumped to his feet but failed to dash through the door, being arrested by the clutch of four arms, and silenced by a hardened hand over his mouth. The men had come from behind, and wore the livery, he saw, of his aunt.

They took him away. He struggled as much as he could but they lifted him up from the step and swept him down the stairs of the turnpike, while his father's sister Lucia-the spy! the traitor!-actually knelt at the door in his place.

Unwitnessed by Henry de St Pol, the vicomte de Rib?rac remained seated inside the chamber and watched his cursing son clutch his bruised head.

'I should have done it before,' said his lordship. 'Your choice of language would disgrace a pig-gutter. The topic is distasteful enough as it is. Let us finish. You and the girl served each other. She married. Now the wedding is over, will it amuse her to tell vander Poele what has happened?'

'Christ!' said Simon de St Pol. 'How do I know? I hope not. I want to tell him myself. I'd like him to know whose lap she came to him from. I'd planned to tell him in Bruges, once they'd married, and we'd got our concessions.'

'But you didn't?' said the vicomte de Rib?rac.

'No. Well, there was the threat of plague in the town. You didn't stay for the Burgundy wedding. After it, the Duke rode off to Holland, and his Duchess left on her tour. There was no one left.'

'Not even vander Poele?' Jordan de Rib?rac said. 'He didn't go with his bride?'

'He could hardly go with the Duchess,' said Simon. 'He may have finished up in the suite of the Duke, but I couldn't reach him. I left. But don't worry, I'll tell him. I'll pick a moment he'll never forget.'

'You think so,' said his father. He got to his feet, drawing his sword. Crossing the floor, he lowered the tip and threaded the fallen pomander on the point of the steel, so that it hung on the blade like an apple. He lifted the weapon, viewing it from end to end. Then he raised his eyes to his son.

'How wrong you are. You will now listen to me. You will not boast to vander Poele that you have ravished his lady. You will ensure that his wife admits nothing. You will, if it pleases you, oppose him as much as you like in sport, or business, or chivalry, and you will prevail if you can. But you will not, you will not advertise your misconduct with a member of the van Borselen family. They are too powerful to offend.'

'Old Henry? Wolfaert?' said Simon. 'You expect them to take ship and challenge me?'

'I expect your trade-our trade-with Flanders to come to a halt. I remind you that Henry van Borselen, lord of Veere, is the grand-uncle of the unfortunate child who was present just now, and the uncle of Gelis van Borselen. I further remind you that Gelis van Borselen held royal office in Scotland: a Burgundian position of honour with the King's older sister. And lastly, although I am sure you would rank this the least, I should point out that there is someone who, if he knew, would certainly abandon his truce and take ship forthwith to challenge you.'

'Vander Poele?' his son said. 'You are trying to frighten me with the cuckold himself?'

'On the contrary,' said the vicomte. 'I said you would perceive it as the least of your worries. But I have given you other reasons enough. You will not broadcast this unfortunate conquest.'

'Or you will do what?' said Simon de St Pol. 'Run me through? Cease to settle my wine bills? What harm can you do to me now?'

The old man regarded him. Despite the weight of the sword, he had not allowed it to lower. He said, 'I could strike you again. And this time you might permit yourself to respond. Is that a threat, or merely a rash invitation? Only you know.'

'It is a rash invitation,' said Simon. Round the bruise, he had become very pale.

'I think,' said his father, 'that you understand yourself very little. But still. Let me summon my auxiliary arguments . . .'

HENRY HAD OFTEN considered killing his grandfather; there was so much of him, and Henry disliked all of it.

Today the impulse came back quite strongly when, sticking his head upside down through the casement, he discovered the old man himself riding over the Kilmirren drawbridge. He could see his big hat, and the pennants, and the baggage-mules, and the men in half-armour to protect what was in all the boxes. They hadn't sounded their trumpets, and below in the courtyard people were scampering in every direction, attempting to help with the horses or even running away. No one liked Henry's grandfather.

Monseigneur Jourdain, the servants called him. It meant Chamberpot. His real name was Jordan de St Pol, vicomte de Rib?rac, and all this castle of Kilmirren was his, and the yards and trees and bothies that Henry looked down on, and the good farmlands and villages just beyond that Henry's father was supposed to look after. This was Monseigneur's Scottish castle, which he came to examine most years. The rest of the time he stayed in France.

Usually, everybody knew when to expect him. The message would come, and his father would curse, and then there would be a week when everyone was in a bad temper, trying to put things to rights. Then on the day, his father would stand in the doorway with Henry, his only son, at his side, and they would both welcome the old man as if they meant it. Fat Father Jordan was how his father referred to him.

Today, there had been no warning, which was terrible. No one knew better than Henry just how terrible it actually was. Henry set aside the hawk he had been feeding and, whirling down from his room, shoved open the door to his father's great chamber.

The bedcurtains were only half closed, so that he could see, with a pang of admiration and interest, what was happening behind them. Even now, in an emergency, he knew better than to interrupt. When it was finished (the signs were familiar) he said shrilly, 'Father! Father! Monseigneur is here!'

The first face to appear was the lady's. He had seen her before. She looked flushed, but didn't giggle like Beth or conceal herself with the sheet like the other one. This lady frowned at him, certainly, but bent and picked up her robe like an ordinary person. Like all his father's ladies, she was well set up as to the chest. Henry's friends all mentioned that, and the servants. They, too, were proud of his father. Henry used to wonder, now and then, if his mother had been flat in front like himself. She had died when Henry was three, but he didn't miss her. He didn't know why people thought he ought to miss her. He said, 'Father?' again, in case he had gone back to sleep.

'God's blood and bones,' said his father, and rolled over and pushed himself up.

Even angry, his father Simon was beautiful. Blond and blue-eyed and beautiful, and the finest jouster, the most splendid chevalier in the whole of Scotland. When Henry's grandfather was dead, Henry's father would be the lord of this castle and its grazing in the mid-west of Scotland. He would own his grandfather's castle in France, and his ships and his mills and his vineyards. His father would be Simon de St Pol, vicomte de Rib?rac, and Henry would be his sole son and heir, and a knight, with ladies to bounce with in bed. Flattish ladies, to be truthful, for preference.

God smote Henry then in the back. Henry was nervous of God. At once he saw, with relief, that it was the door, flung crashing open, which had pushed him aside. Then the relief promptly died, for in the entrance stood Jordan de St Pol, vicomte de Rib?rac, who was fatter than God and clean-shaven. Monseigneur Jourdain, his grandfather.

His grandfather said, 'Get rid of the bawd.'

'Bawd!' said the lady.

'I beg your pardon,' said his grandfather, looking at her. 'My lady, will you excuse us? And-Henry? I see your father is furthering your education?'

He didn't know what to say. 'Go!' muttered his father in no special direction.

'I should prefer to dress,' said the lady.

'Then pray do,' said Monseigneur. 'We see you don't mind an audience. I might even be more appreciative than a seven-year-old. Henry, I shall speak to you later.'

'Simon?' said the lady.

'I think you'd better dress in Henry's room,' said his father. 'Henry will show you the way. I apologise for the vicomte. Although he does not lodge in this wing, he seems to feel entitled to go where he pleases. Henry?'

Henry said, 'She can go somewhere else. I've got hawks in my room.'

'That, of course, must take precedence. So take her somewhere else, Henry,' said his grandfather. 'And then return to your room until I call for you.'

He took her somewhere else, but instead of returning to his room, he crept back to the half-open door, behind which his grandfather was haranguing his father. He could see them by holding the tapestry back just a little. If he were his father, he would knock him down. If his grandfather lifted a hand to his father he, Henry, would rush in and kill him. With the fire-tongs. With anything. He listened.

It was the old story. You would think that at last it didn't matter, whether the crops were sown a bit late or the hides not always cured to perfection or the smithwork patchy, or the peats left cut and lying too long. With the money from Madeira and the African voyage, they had enough to buy clothes with for years-even his silly aunt Lucia said so. And silver harness, and hawks, and jousting-armour. He had seen his father's new jousting-armour. You would think even his grandfather would be impressed, instead of threatening to get rid of Hugo and Steen, who had run the house and the land all the time his father was in Madeira and Flanders and Portugal. If Hugo and Steen were no good, why was his father being blamed for not staying in Flanders?

Flanders was a country far to the south, further south than England, across the Narrow Sea. Flanders was ruled by the Duke of Burgundy, the richest prince in the world. Henry had never been to Flanders.

'I cut short my visit to Bruges,' his grandfather said, 'because I bear a French title, and should be far from welcome at the Duke of Burgundy's wedding. But Kilmirren sends cargoes to Flanders. Why did you leave?'

Chamberpot Jordan. He occupied the only big chair like a throne. Everything about his father's father was big: his height, his width, the huge rolled hat on his head, the thick coat, the long robe, the solid boots. His hair was grey, and the whites of his eyes were yellow. He was old. He was over sixty years old and would live for ever, his father said, because he kept the accounts of the devil. His father had got out of bed and, without hurrying, had pulled on a gown without fastening it. His father had a narrow, ridged shape like Jesus. The old man said, 'You had a meeting with Nicholas.'

'Who?' said his father. He sat down on the platform-base of the bed and pulled on his slippers. Then he got up without an excuse and busied himself round the door of the privy. Henry felt hot. He knew who Nicholas was. Nicholas vander Poele, a wicked tradesman from Bruges who hated and cheated his father, if he could. But his father always won.

His father came back and sat down on the bed-base. 'Good. Are you comfortable?' said his grandfather. 'How unfortunate that we always seem to meet when your physique and intellect are both at their feeblest. I asked about your meeting with Nicholas. It was, as I remember, to determine the fate of two court cases. What was the outcome?'

His father laughed. The colour had come back to his skin. 'What do you think? He gave in. He promised not to take us to law over one ship, if we would agree not to contest possession of the other. We were lucky. He could have caused us some trouble.'

'So why didn't he?' the old man said.

His father had started to dress. Since Madeira, all his clothes were of silk. 'Who knows? Jellied in the brain from the African suns. He doesn't even claim us as kin any more. I wish he'd told me beforehand. I might have spared the mattress a little.'

The look that Henry feared had congealed upon his grandfather's face. His grandfather said, 'I am not sure what you mean.'

'I mean I got Gelis van Borselen under me,' his father said. 'Here, this summer. She made a little visit to Scotland six weeks before vander Poele married her. Now he's wedded my leavings. How's that?' He went on tying his points to his shirt. After a while, he looked up.

'Your late wife's sister,' said Grandfather Jordan reflectively. 'You seduced your sister by marriage, Gelis van Borselen of Veere, related to the rulers of Scotland and Burgundy? You raped her in advance of her wedding, because Nicholas vander Poele was her affianced husband?'

'Raped her!' his father said in mild protest. 'When did I ever need to do that? The girl was born with an itch, like her sister.'

The old man made a sound with his teeth, then resumed. 'In spite of which, she went back to Bruges. She did marry?'

'Of course she did!' his father said. 'He's settled half his fortune on her-half the gold he brought back from Africa. She'll be the richest woman in Flanders, and safe. He'd never know on the night. A well-trodden path, as they say, shows no prints.'

He smiled at the thought, and the smile broadened into a yawn. 'I've no complaints, and she won't soon forget it. She wanted to find out what her sister enjoyed, and she did.' He stopped smiling and flung up an arm. 'Damn you!' he exclaimed.

It was so quick, the movement of his grandfather's wrist, the pomander striking its target, the crash as the pierced silver ball fell to the floor, that Henry had no time to move. He heard his father cry out and saw the punch-mark on his brow where the skin began to turn bluish-red. Then his father roared, 'Damn you!' again.

It was why Henry was there, to protect him. He had his fists; he could kick. He jumped to his feet but failed to dash through the door, being arrested by the clutch of four arms, and silenced by a hardened hand over his mouth. The men had come from behind, and wore the livery, he saw, of his aunt.

They took him away. He struggled as much as he could but they lifted him up from the step and swept him down the stairs of the turnpike, while his father's sister Lucia-the spy! the traitor!-actually knelt at the door in his place.

Unwitnessed by Henry de St Pol, the vicomte de Rib?rac remained seated inside the chamber and watched his cursing son clutch his bruised head.

'I should have done it before,' said his lordship. 'Your choice of language would disgrace a pig-gutter. The topic is distasteful enough as it is. Let us finish. You and the girl served each other. She married. Now the wedding is over, will it amuse her to tell vander Poele what has happened?'

'Christ!' said Simon de St Pol. 'How do I know? I hope not. I want to tell him myself. I'd like him to know whose lap she came to him from. I'd planned to tell him in Bruges, once they'd married, and we'd got our concessions.'

'But you didn't?' said the vicomte de Rib?rac.

'No. Well, there was the threat of plague in the town. You didn't stay for the Burgundy wedding. After it, the Duke rode off to Holland, and his Duchess left on her tour. There was no one left.'

'Not even vander Poele?' Jordan de Rib?rac said. 'He didn't go with his bride?'

'He could hardly go with the Duchess,' said Simon. 'He may have finished up in the suite of the Duke, but I couldn't reach him. I left. But don't worry, I'll tell him. I'll pick a moment he'll never forget.'

'You think so,' said his father. He got to his feet, drawing his sword. Crossing the floor, he lowered the tip and threaded the fallen pomander on the point of the steel, so that it hung on the blade like an apple. He lifted the weapon, viewing it from end to end. Then he raised his eyes to his son.

'How wrong you are. You will now listen to me. You will not boast to vander Poele that you have ravished his lady. You will ensure that his wife admits nothing. You will, if it pleases you, oppose him as much as you like in sport, or business, or chivalry, and you will prevail if you can. But you will not, you will not advertise your misconduct with a member of the van Borselen family. They are too powerful to offend.'

'Old Henry? Wolfaert?' said Simon. 'You expect them to take ship and challenge me?'

'I expect your trade-our trade-with Flanders to come to a halt. I remind you that Henry van Borselen, lord of Veere, is the grand-uncle of the unfortunate child who was present just now, and the uncle of Gelis van Borselen. I further remind you that Gelis van Borselen held royal office in Scotland: a Burgundian position of honour with the King's older sister. And lastly, although I am sure you would rank this the least, I should point out that there is someone who, if he knew, would certainly abandon his truce and take ship forthwith to challenge you.'

'Vander Poele?' his son said. 'You are trying to frighten me with the cuckold himself?'

'On the contrary,' said the vicomte. 'I said you would perceive it as the least of your worries. But I have given you other reasons enough. You will not broadcast this unfortunate conquest.'

'Or you will do what?' said Simon de St Pol. 'Run me through? Cease to settle my wine bills? What harm can you do to me now?'

The old man regarded him. Despite the weight of the sword, he had not allowed it to lower. He said, 'I could strike you again. And this time you might permit yourself to respond. Is that a threat, or merely a rash invitation? Only you know.'

'It is a rash invitation,' said Simon. Round the bruise, he had become very pale.

'I think,' said his father, 'that you understand yourself very little. But still. Let me summon my auxiliary arguments . . .'

Recenzii

"The finest living writer of historical fiction" —The Washington Post Book World

"Alive with spectacle and pageantry....[Her] army of fans...should continue to swell.... Dunnett has done it again." —The Washington Post Book World

"Another rousing, utterly convincing adventure.... Readers are bound to ask for more." —Kirkus Reviews

"Alive with spectacle and pageantry....[Her] army of fans...should continue to swell.... Dunnett has done it again." —The Washington Post Book World

"Another rousing, utterly convincing adventure.... Readers are bound to ask for more." —Kirkus Reviews

Descriere

The fifth book in the House of Niccolo series finds Nicholas on a chase from Scotland to Venice to avenge his bride's claim that she carries the bastard of his arch enemy, Simon St. Pol. Map.