The Virgins

Autor Pamela Erensen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 ian 2014

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 67.81 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| HODDER AND STOUGHTON LTD – 29 ian 2014 | 67.81 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Tin House Books – 5 aug 2013 | 91.11 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 132.93 lei 17-23 zile | |

| John Murray Publishers – 30 ian 2014 | 132.93 lei 17-23 zile |

Preț: 67.81 lei

Preț vechi: 88.96 lei

-24% Nou

Puncte Express: 102

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.98€ • 14.09$ • 10.90£

12.98€ • 14.09$ • 10.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781848549906

ISBN-10: 1848549903

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 214 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: HODDER AND STOUGHTON LTD

Colecția John Murray

ISBN-10: 1848549903

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 214 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: HODDER AND STOUGHTON LTD

Colecția John Murray

Recenzii

* A New York Times Editor's Choice selection

* A Chicago Tribune Editor's Choice selection

* A Best Book of 2013, The New Yorker

* A Best Book of 2013, The New Republic

* A Critics' Choice selection for 2013, Salon

* A Best Indie Title of 2013, Library Journal

* One of Redbook's "Top Ten Beach Reads of 2013"

* One of O Magazine's "Ten Titles to Pick Up Now," August 2013

* Featured in The Millions's "Most-Anticipated" List 2013

* A "This Week's Hot Reads" selection, The Daily Beast

* A Vanity Fair Hot Type selection

* The Virgins was a finalist for the John Gardner Award

* Publishers Weekly named The Virgins one of the best boarding school books of all time

". . .The Virgins is both skillfully crafted and dangerous . . .Pamela Erens [has] told a devastating story. The Virgins is a brutal book, but it's flawlessly executed and irrefutably true."

—John Irving, New York Times Book Review

"Adroitly capturing the anguish of adolescent desire, Erens's latest is a lesson in love, loss, and tragedy."

—Publishers Weekly

"Erens writes with great believability and sensitivity about the teenage years, when school and family pressures, along with sexual awakening, can seem like life-and-death issues. Whether she's describing a visit to an ice cream stand or Seung and Aviva's explorations of lovemaking, her prose is sensual and lyrical. . .Many readers will want to investigate this work."

—Library Journal

"As in many budding relationships, the best part of Erens’s recent novel is simply the suggestion of sex. In The Virgins, we join the author’s two college characters for their early explorations of one another and watch them through the voyeuristic perspective of another student."

—Time Out New York

"This newest addition to the 'boarding school novels we love' category mixes the unsettling drama of A Separate Peace with the sexual juiciness of Prep. . .The dark twist of an ending will haunt you for days."

—Redbook.com

"Perhaps it is going too far to say that The Virgins is primarily about the fundamental flaws of white, male narrators in fiction. It is also about sex, fear—especially of authority—class, desire, shame and jealousy. But in reveling in the power of narrative, the book asks the reader to think about who is—and who has been—allowed to wield it."

—The New York Observer

"With The Virgins, Pamela Erens' intricate second novel, she has done a star turn with the prep school tale, giving it meaning for those who might not usually care about that world."

—The Chicago Tribune, Editor's Choice

"It's rare to find a book that summons the delicate emotional state of teenagers — especially when it comes to sex — without being precious or cynical, but Pamela Erens' The Virgins beautifully manages that feat."

—Los Angeles Times

"[Erens] manages a delicate bit of witchcraft such that, by halfway through the novel, our fingertips are humming on the page. And that is due to the way she summons so intensely the momentousness of adolescence, when everything feels big and important, and every moment feels like the one after which you will never be the same again."

—The Guardian

"On par with the likes of Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides and Sheila Kohler’s Cracks, The Virgins is a devastating tour de force that sets a new bar for unreliable narrators."

—The Independent

"A devilish narrator looks back on his boarding school days, when he and another young man develop an obsession with the new girl on campus. But he tells their story in a voyeuristic way, to make this one of the most troubling and serpentine novels of the year."

—The Daily Beast

"Outsiders at a prestigious East Coast boarding school in 1979, Aviva Rossner and Seung Jung find and then tragically lose each other. Rarely has the anguish of young love, self-discovery, and sexual jealousy—heightened by the sting of class division—been rendered so tellingly."

—Library Journal

"In her second novel, The Virgins, Pamela Erens paints an arresting portrait of adolescent sexuality — at once beautiful, erotic, awkward, and shameful. With its racial tensions, vile narrator, and tragic climax, The Virgins reads like a prep school Othello, set to a soundtrack of Devo and Jethro Tull."

—Leigh Stein, Los Angeles Review of Books

"In Pamela Erens’s evocative second book, The Virgins, boarding school is a microcosm of society, with its strict social norms that frown on blatant sexuality."

—The Rumpus

"With a lyrical voice, Pamela Erens has written a novel about first love and sexual awakening that is multilayers and perceptive...[The Virgins] is thickly layered with prose that intrigues the mind and captivates the senses."

—Foreword Reviews

"The metaphysics of The Virgins [is] that the potential eroticism in all things makes them all secretly significant."

—Slate

"Erens brilliantly captures that time when someone is determined to give up virginity and how all-consuming sex becomes. She writes about the mystique, the slow building and the machinations Seung and Aviva experience."

—New Jersey Star Ledger

"The Virgins does qualify as a new classic and students of the form will read it again and again."

—Gently Read Literature

"Virginity is treated with. . .grace and subtlety in Pamela Erens’s latest novel, The Virgins (Tin House Books), a beautifully written story about two outcasts who form an all-consuming bond at an exclusive boarding school, as told, in secretive, sweaty detail, by a rather odious classmate."

—Vulture.com

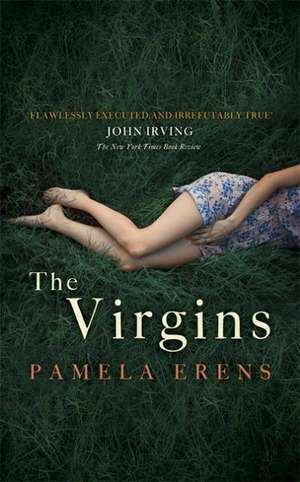

"With a cover like this, who could resist a peek? What lay inside was even more riveting than the titillating, slightly disturbing, Lolita-esque photo that first encouraged me to have a go. A prep-school saga about sex, rumors, young love, and adult regret,The Virgins encouraged its readers to feel as frenzied, and libidinous, and strung out as a 17-year-old in the throes of first lust. This small, smart masterpiece is a beautiful shot of adrenaline—with a terrifying come down."

—Hillary Kelly, The New Republic

"This is some of the strongest literary fiction I've read in a while..."

—The Tattered Cover

"The Virgins reminded me how gratifying it is to fall into a good novel—one that feeds the senses and makes us think."

—The Common Online

"As an editor, I can say this is one of the most finely crafted books I’ve read. The fresh approach of a narrator who is imagining our scenes adds a compelling filter who still feels trustworthy. . .Erens handling of the characters sexuality and the grace with which she handles the sex scenes—with teenagers—deserves a separate round of applause. . .As a reader, I was simply moved."

—The Painted Bride Quarterly, Drexel University

"Now that James Salter is in his twilight years, his considerable fan base will be ecstatic to encounter his heiress apparent, Pamela Erens, whose erotically charged prose reaches for naming the ineffable, honoring the elusive, and celebrating the bodily majesty of life. An extraordinary novel."

—Antonya Nelson, author of Bound

"A sensual and haunting story of sexual awakening, Pamela Erens’s exquisitely written The Virgins vividly captures the thrill of youthful innocence and the crushing pain of its loss. This is a profound—and profoundly moving—novel. I couldn't put it down, and I didn't want it to end."

—Will Allison, author of Long Drive Home

"Suspenseful and swift and well made, The Virgins, Pamela Erens's exciting new fiction, ratchets up the heat on the boarding school novel with ferociously sensual descriptions of frustrated love—love imagined and love experienced. Easy to fall for this book and fall hard."

—Christine Schutt, author of Prosperous Friends

“Like the unforgettable Aviva Rossner, The Virgins is small but not slight—intense, sublime, vivid, uncanny, irresistible. It joins the ranks of the great boarding school novels while somehow evoking the twisted, obsessive narrations of Nabokov’s Pale Fire or Wharton’s Ethan Frome. Pamela Erens is that rare writer who can articulate—and gorgeously—the secrets we never knew about ourselves."

—Rebecca Makkai, author of The Borrower

“The Virgins is a stunningly beautiful novel. It is precisely observed, skillfully constructed, and brilliantly written. This is possibly the best novel of the many good ones set in a New England prep school, that terrain of elegance and envy, of flowering and blight.”

—John Casey, National Book Award-winning author of Spartina

* A Chicago Tribune Editor's Choice selection

* A Best Book of 2013, The New Yorker

* A Best Book of 2013, The New Republic

* A Critics' Choice selection for 2013, Salon

* A Best Indie Title of 2013, Library Journal

* One of Redbook's "Top Ten Beach Reads of 2013"

* One of O Magazine's "Ten Titles to Pick Up Now," August 2013

* Featured in The Millions's "Most-Anticipated" List 2013

* A "This Week's Hot Reads" selection, The Daily Beast

* A Vanity Fair Hot Type selection

* The Virgins was a finalist for the John Gardner Award

* Publishers Weekly named The Virgins one of the best boarding school books of all time

". . .The Virgins is both skillfully crafted and dangerous . . .Pamela Erens [has] told a devastating story. The Virgins is a brutal book, but it's flawlessly executed and irrefutably true."

—John Irving, New York Times Book Review

"Adroitly capturing the anguish of adolescent desire, Erens's latest is a lesson in love, loss, and tragedy."

—Publishers Weekly

"Erens writes with great believability and sensitivity about the teenage years, when school and family pressures, along with sexual awakening, can seem like life-and-death issues. Whether she's describing a visit to an ice cream stand or Seung and Aviva's explorations of lovemaking, her prose is sensual and lyrical. . .Many readers will want to investigate this work."

—Library Journal

"As in many budding relationships, the best part of Erens’s recent novel is simply the suggestion of sex. In The Virgins, we join the author’s two college characters for their early explorations of one another and watch them through the voyeuristic perspective of another student."

—Time Out New York

"This newest addition to the 'boarding school novels we love' category mixes the unsettling drama of A Separate Peace with the sexual juiciness of Prep. . .The dark twist of an ending will haunt you for days."

—Redbook.com

"Perhaps it is going too far to say that The Virgins is primarily about the fundamental flaws of white, male narrators in fiction. It is also about sex, fear—especially of authority—class, desire, shame and jealousy. But in reveling in the power of narrative, the book asks the reader to think about who is—and who has been—allowed to wield it."

—The New York Observer

"With The Virgins, Pamela Erens' intricate second novel, she has done a star turn with the prep school tale, giving it meaning for those who might not usually care about that world."

—The Chicago Tribune, Editor's Choice

"It's rare to find a book that summons the delicate emotional state of teenagers — especially when it comes to sex — without being precious or cynical, but Pamela Erens' The Virgins beautifully manages that feat."

—Los Angeles Times

"[Erens] manages a delicate bit of witchcraft such that, by halfway through the novel, our fingertips are humming on the page. And that is due to the way she summons so intensely the momentousness of adolescence, when everything feels big and important, and every moment feels like the one after which you will never be the same again."

—The Guardian

"On par with the likes of Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides and Sheila Kohler’s Cracks, The Virgins is a devastating tour de force that sets a new bar for unreliable narrators."

—The Independent

"A devilish narrator looks back on his boarding school days, when he and another young man develop an obsession with the new girl on campus. But he tells their story in a voyeuristic way, to make this one of the most troubling and serpentine novels of the year."

—The Daily Beast

"Outsiders at a prestigious East Coast boarding school in 1979, Aviva Rossner and Seung Jung find and then tragically lose each other. Rarely has the anguish of young love, self-discovery, and sexual jealousy—heightened by the sting of class division—been rendered so tellingly."

—Library Journal

"In her second novel, The Virgins, Pamela Erens paints an arresting portrait of adolescent sexuality — at once beautiful, erotic, awkward, and shameful. With its racial tensions, vile narrator, and tragic climax, The Virgins reads like a prep school Othello, set to a soundtrack of Devo and Jethro Tull."

—Leigh Stein, Los Angeles Review of Books

"In Pamela Erens’s evocative second book, The Virgins, boarding school is a microcosm of society, with its strict social norms that frown on blatant sexuality."

—The Rumpus

"With a lyrical voice, Pamela Erens has written a novel about first love and sexual awakening that is multilayers and perceptive...[The Virgins] is thickly layered with prose that intrigues the mind and captivates the senses."

—Foreword Reviews

"The metaphysics of The Virgins [is] that the potential eroticism in all things makes them all secretly significant."

—Slate

"Erens brilliantly captures that time when someone is determined to give up virginity and how all-consuming sex becomes. She writes about the mystique, the slow building and the machinations Seung and Aviva experience."

—New Jersey Star Ledger

"The Virgins does qualify as a new classic and students of the form will read it again and again."

—Gently Read Literature

"Virginity is treated with. . .grace and subtlety in Pamela Erens’s latest novel, The Virgins (Tin House Books), a beautifully written story about two outcasts who form an all-consuming bond at an exclusive boarding school, as told, in secretive, sweaty detail, by a rather odious classmate."

—Vulture.com

"With a cover like this, who could resist a peek? What lay inside was even more riveting than the titillating, slightly disturbing, Lolita-esque photo that first encouraged me to have a go. A prep-school saga about sex, rumors, young love, and adult regret,The Virgins encouraged its readers to feel as frenzied, and libidinous, and strung out as a 17-year-old in the throes of first lust. This small, smart masterpiece is a beautiful shot of adrenaline—with a terrifying come down."

—Hillary Kelly, The New Republic

"This is some of the strongest literary fiction I've read in a while..."

—The Tattered Cover

"The Virgins reminded me how gratifying it is to fall into a good novel—one that feeds the senses and makes us think."

—The Common Online

"As an editor, I can say this is one of the most finely crafted books I’ve read. The fresh approach of a narrator who is imagining our scenes adds a compelling filter who still feels trustworthy. . .Erens handling of the characters sexuality and the grace with which she handles the sex scenes—with teenagers—deserves a separate round of applause. . .As a reader, I was simply moved."

—The Painted Bride Quarterly, Drexel University

"Now that James Salter is in his twilight years, his considerable fan base will be ecstatic to encounter his heiress apparent, Pamela Erens, whose erotically charged prose reaches for naming the ineffable, honoring the elusive, and celebrating the bodily majesty of life. An extraordinary novel."

—Antonya Nelson, author of Bound

"A sensual and haunting story of sexual awakening, Pamela Erens’s exquisitely written The Virgins vividly captures the thrill of youthful innocence and the crushing pain of its loss. This is a profound—and profoundly moving—novel. I couldn't put it down, and I didn't want it to end."

—Will Allison, author of Long Drive Home

"Suspenseful and swift and well made, The Virgins, Pamela Erens's exciting new fiction, ratchets up the heat on the boarding school novel with ferociously sensual descriptions of frustrated love—love imagined and love experienced. Easy to fall for this book and fall hard."

—Christine Schutt, author of Prosperous Friends

“Like the unforgettable Aviva Rossner, The Virgins is small but not slight—intense, sublime, vivid, uncanny, irresistible. It joins the ranks of the great boarding school novels while somehow evoking the twisted, obsessive narrations of Nabokov’s Pale Fire or Wharton’s Ethan Frome. Pamela Erens is that rare writer who can articulate—and gorgeously—the secrets we never knew about ourselves."

—Rebecca Makkai, author of The Borrower

“The Virgins is a stunningly beautiful novel. It is precisely observed, skillfully constructed, and brilliantly written. This is possibly the best novel of the many good ones set in a New England prep school, that terrain of elegance and envy, of flowering and blight.”

—John Casey, National Book Award-winning author of Spartina

Notă biografică

Pamela Erens was raised in Chicago and attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Yale University, where she concentrated on literary theory and women’s studies. For many years she worked as a magazine editor, including at Glamour. Her editing and freelance journalism have won national awards.

Erens’s first novel, The Understory, published in 2007, was the winner of the Ironweed Press Fiction Prize and a finalist for both the 2007 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for First Fiction and the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing. Erens has also published short fiction, poetry, and essays in literary journals and magazines ranging from Chicago Review and New England Review to O: The Oprah Magazine. She is the recipient of two New Jersey State Council on the Arts fellowships in fiction and was a Tennessee Williams Scholar at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference.

Erens’s first novel, The Understory, published in 2007, was the winner of the Ironweed Press Fiction Prize and a finalist for both the 2007 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for First Fiction and the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing. Erens has also published short fiction, poetry, and essays in literary journals and magazines ranging from Chicago Review and New England Review to O: The Oprah Magazine. She is the recipient of two New Jersey State Council on the Arts fellowships in fiction and was a Tennessee Williams Scholar at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference.

Extras

Chapter 1:

1979

We sit on the benches and watch the buses unload. Cort, Voss, and me.

We’re high school seniors, at long last, and it’s the privilege of seniors to take up these spots in front of the dormitories, checking out the new bodies and faces. Boys with big glasses and bangs in their eyes, girls with Farrah Fawcett hair. Last year’s girls have already been accounted for: too ugly or too studious or too strange, or already hitched up, or too gorgeous even to think about.

It’s long odds, we know: one girl here for every two boys. And the new kids don’t tend to come on these buses shuttling from the airport or South Station. Their anxious parents cling to the last hours of control and drive them, carry their things inside the neat brick buildings, fuss, complain about the drab, spartan rooms. If there’s a pretty girl among them, you can’t get close to her for the mother, the father, the scowling little brother who didn’t want to drive hundreds of miles to get here. We don’t care about the new boys, of course. We’ll get to know them later. Or not.

She turns her ankle as she comes down the bus steps--just a little wobble--laughs, and rights herself again. Her sandals are tapered and high. Only a tiny heel connects with the rubber-coated steps. She wears a silky purple dress, slit far up the side, and a white blazer. Her outfit is as strange in this place--this place of crew-neck sweaters and Docksiders--as a clown’s nose and paddle feet. Her eyes are heavily made up, blackened somehow, sleepy, deep. She waits on the pavement while the driver yanks up the storage doors at the side. She points and he pulls out two enormous matching suitcases, fabric-sided, bright yellow. His muscles bulge lifting them onto the pavement.

I jump up. Cort and Voss are still computing, trying to figure this girl out, but I don’t intend to wait. Voss makes a popping sound with his lips, to mock me and to offer his respectful surprise. After all, I supposedly already have a girlfriend.

“Do you need some help?” I ask her.

She smiles slowly, theatrically. Her teeth are very straight, very white. Orthodontia or maybe fluoride in the water. I wonder where she’s from. City, fancy suburb? It suddenly hits me. She’s one of those. I can see it in her dark eyes, the bump in her nose, her thick, dark, kinky hair.

“I’m in Hiram,” she says.

Let me recreate her journey.

She awakens in her big room at an hour when it is still dark, pushes open the curtains of her four-poster bed. Little princess. Across the hall, her brother is still sleeping. He’s four years younger than she is: twelve. She makes herself breakfast: a bagel with cream cheese, O.J., and a bowl of Cheerios; she’s always ravenous in the morning. She eats alone. Her mother, in her bathrobe, reads stacks of journals upstairs. Her father is shaving. He doesn’t like to eat in the morning. He brings her to the airport but they say nothing during the long drive through the flat gray streets of Chicago. She hopes that he’ll say he’ll miss her, that he’ll pretend this parting takes something out of him. She was the one who asked to go away, but in the car her belly acts up, she’s queasy. She thinks she may need to rush to the bathroom as soon as they get to O’Hare. She wishes she hadn’t eaten so much. If her father would act like he might miss her, is afraid for her, she could be a little less afraid for herself. She has practiced her walk, her talk, everything she needs to present herself. She is terrified of going somewhere new simply to end up invisible again.

One long heel sinks into the mud. The past days have brought late-summer rains to New Hampshire, and although the air is now dry, the grass between the parking areas and the dormitories is soft and mucky. This is a girl used to walking on city pavement, concrete. She laughs and pulls herself out. She is determined to make it seem as if everything that happens to her is something she meant to happen, or can gracefully control. She avoids the wetter grass but in a moment she sinks again. “Oh boy,” she says. Her dress is long, almost to her ankles. I put down her suitcases and hold out my hand; she takes it and I pull. Her freed shoe makes a sucking sound. When I go over the sound in my mind later, it strikes me as obscene. Her suitcases are heavy, heavy as I’ve since learned only a woman’s luggage can be. It’s only a little farther to her dorm. She tells me that she’s an upper--what other high schools call a junior--and we exchange names. Aviva Rossner. She repeats mine, Bruce Bennett-Jones, like she’s thinking it over, trying to decide if it’s a good one.

She walks ahead of me instead of following, perhaps intending me to watch her small ass shifting under the white jacket. The wind lifts the hem of her dress, pastes it against her long bare leg. The Academy flag whips around above us and clings to the flagpole in the same way. The smell of ripened apples floods the air. We’re on the pavement, finally; she click-clacks to the heavy door and opens it for me. Strong arms on such a slender girl. Someone’s playing piano in the common room, a ragtime tune. Aviva starts up the stairs, expecting me to bring the bags. It’s strictly against the rules for a boy to go up to the residential floors. I go up.

Inside the dorm, the light is dim. The walls are cream-colored and dingy, the floors ocher. She counts out the door numbers until she finds hers: 21. I put the suitcases by the dresser, the same plain wooden dresser that sits in my room and in every student room on campus. Her suitcases contain—we’ll all see in the days to come—V-necked angora sweaters, slim skirts, socks with little pom-poms at the heels, teeny cut-off shorts, cowboy boots, lots of gold jewelry, many pouches of makeup.

There’s a mirror above the dresser. I catch a view of myself: sweaty forehead, damp curls. Aviva’s roommate is not here yet. The closet yawns open, wire hangers empty.

“Thank you so much,” she says.

I give the front door a push. It hits dully against the frame, doesn’t shut. Aviva has plenty of time to do something: slip into the hallway, order me to go away. She regards me with a patient smile. I am going to slow down the action now, relating this; I want to see it all again very clearly. Like a play being blocked--my stock-in-trade. And so: I push again and the door grinding shut is the loudest and most final sound I have ever heard. Aviva steps back to lean against it and let me approach. She’s a small girl and moving close to her I feel, for once, that I have some size. The waxy collar of her jacket prickles the hair on my forearms. Her neck is damp and slippery, and her mouth, as I kiss it, tastes like cigarettes and chocolate. I picture her smoking rapidly, furtively, in the little bathroom on the plane. Her hair smells a little rancid. The perfume she put on this morning has moldered with sweat and travel and now gives off an odor of decayed pear.

“Don’t open your mouth so wide,” she says.

My feet are sweating in my sneakers. My crotch itches. My scalp itches. She drops her hand and I see that her fingernails are painted a pearly pink.

She tilts her head against the door and laughs. Her thick curls swarm. I could bite her exposed neck. I do not want to get caught, sent home. I see my father’s hand raised up to hit me and know I’m about to step off a great ledge. In a panic I reach for the doorknob, startling Aviva. I open the door carefully, listen to the stairs and hallways. “It’s all right,” she says, although how can she know this? But she happens to be correct. There’s the oddest emptiness and silence as if these moments and this place were set aside just for us amid the busyness of moving-in day at the Academy. Aviva gives the door a bump with her ass to shut it again, but I insert myself into the opening and slide past her, fleeing down the stairs and out into Hiram’s yard.

Cort and Voss are no longer sitting on the bench in front of Weld. A lone bicycle is chained to its arm.

Later I see Voss in the common room reading a New Gods comic book. “How was the chick?” he asks. I shrug. Big nose, I say. Too much makeup. Not my type.

1979

We sit on the benches and watch the buses unload. Cort, Voss, and me.

We’re high school seniors, at long last, and it’s the privilege of seniors to take up these spots in front of the dormitories, checking out the new bodies and faces. Boys with big glasses and bangs in their eyes, girls with Farrah Fawcett hair. Last year’s girls have already been accounted for: too ugly or too studious or too strange, or already hitched up, or too gorgeous even to think about.

It’s long odds, we know: one girl here for every two boys. And the new kids don’t tend to come on these buses shuttling from the airport or South Station. Their anxious parents cling to the last hours of control and drive them, carry their things inside the neat brick buildings, fuss, complain about the drab, spartan rooms. If there’s a pretty girl among them, you can’t get close to her for the mother, the father, the scowling little brother who didn’t want to drive hundreds of miles to get here. We don’t care about the new boys, of course. We’ll get to know them later. Or not.

She turns her ankle as she comes down the bus steps--just a little wobble--laughs, and rights herself again. Her sandals are tapered and high. Only a tiny heel connects with the rubber-coated steps. She wears a silky purple dress, slit far up the side, and a white blazer. Her outfit is as strange in this place--this place of crew-neck sweaters and Docksiders--as a clown’s nose and paddle feet. Her eyes are heavily made up, blackened somehow, sleepy, deep. She waits on the pavement while the driver yanks up the storage doors at the side. She points and he pulls out two enormous matching suitcases, fabric-sided, bright yellow. His muscles bulge lifting them onto the pavement.

I jump up. Cort and Voss are still computing, trying to figure this girl out, but I don’t intend to wait. Voss makes a popping sound with his lips, to mock me and to offer his respectful surprise. After all, I supposedly already have a girlfriend.

“Do you need some help?” I ask her.

She smiles slowly, theatrically. Her teeth are very straight, very white. Orthodontia or maybe fluoride in the water. I wonder where she’s from. City, fancy suburb? It suddenly hits me. She’s one of those. I can see it in her dark eyes, the bump in her nose, her thick, dark, kinky hair.

“I’m in Hiram,” she says.

Let me recreate her journey.

She awakens in her big room at an hour when it is still dark, pushes open the curtains of her four-poster bed. Little princess. Across the hall, her brother is still sleeping. He’s four years younger than she is: twelve. She makes herself breakfast: a bagel with cream cheese, O.J., and a bowl of Cheerios; she’s always ravenous in the morning. She eats alone. Her mother, in her bathrobe, reads stacks of journals upstairs. Her father is shaving. He doesn’t like to eat in the morning. He brings her to the airport but they say nothing during the long drive through the flat gray streets of Chicago. She hopes that he’ll say he’ll miss her, that he’ll pretend this parting takes something out of him. She was the one who asked to go away, but in the car her belly acts up, she’s queasy. She thinks she may need to rush to the bathroom as soon as they get to O’Hare. She wishes she hadn’t eaten so much. If her father would act like he might miss her, is afraid for her, she could be a little less afraid for herself. She has practiced her walk, her talk, everything she needs to present herself. She is terrified of going somewhere new simply to end up invisible again.

One long heel sinks into the mud. The past days have brought late-summer rains to New Hampshire, and although the air is now dry, the grass between the parking areas and the dormitories is soft and mucky. This is a girl used to walking on city pavement, concrete. She laughs and pulls herself out. She is determined to make it seem as if everything that happens to her is something she meant to happen, or can gracefully control. She avoids the wetter grass but in a moment she sinks again. “Oh boy,” she says. Her dress is long, almost to her ankles. I put down her suitcases and hold out my hand; she takes it and I pull. Her freed shoe makes a sucking sound. When I go over the sound in my mind later, it strikes me as obscene. Her suitcases are heavy, heavy as I’ve since learned only a woman’s luggage can be. It’s only a little farther to her dorm. She tells me that she’s an upper--what other high schools call a junior--and we exchange names. Aviva Rossner. She repeats mine, Bruce Bennett-Jones, like she’s thinking it over, trying to decide if it’s a good one.

She walks ahead of me instead of following, perhaps intending me to watch her small ass shifting under the white jacket. The wind lifts the hem of her dress, pastes it against her long bare leg. The Academy flag whips around above us and clings to the flagpole in the same way. The smell of ripened apples floods the air. We’re on the pavement, finally; she click-clacks to the heavy door and opens it for me. Strong arms on such a slender girl. Someone’s playing piano in the common room, a ragtime tune. Aviva starts up the stairs, expecting me to bring the bags. It’s strictly against the rules for a boy to go up to the residential floors. I go up.

Inside the dorm, the light is dim. The walls are cream-colored and dingy, the floors ocher. She counts out the door numbers until she finds hers: 21. I put the suitcases by the dresser, the same plain wooden dresser that sits in my room and in every student room on campus. Her suitcases contain—we’ll all see in the days to come—V-necked angora sweaters, slim skirts, socks with little pom-poms at the heels, teeny cut-off shorts, cowboy boots, lots of gold jewelry, many pouches of makeup.

There’s a mirror above the dresser. I catch a view of myself: sweaty forehead, damp curls. Aviva’s roommate is not here yet. The closet yawns open, wire hangers empty.

“Thank you so much,” she says.

I give the front door a push. It hits dully against the frame, doesn’t shut. Aviva has plenty of time to do something: slip into the hallway, order me to go away. She regards me with a patient smile. I am going to slow down the action now, relating this; I want to see it all again very clearly. Like a play being blocked--my stock-in-trade. And so: I push again and the door grinding shut is the loudest and most final sound I have ever heard. Aviva steps back to lean against it and let me approach. She’s a small girl and moving close to her I feel, for once, that I have some size. The waxy collar of her jacket prickles the hair on my forearms. Her neck is damp and slippery, and her mouth, as I kiss it, tastes like cigarettes and chocolate. I picture her smoking rapidly, furtively, in the little bathroom on the plane. Her hair smells a little rancid. The perfume she put on this morning has moldered with sweat and travel and now gives off an odor of decayed pear.

“Don’t open your mouth so wide,” she says.

My feet are sweating in my sneakers. My crotch itches. My scalp itches. She drops her hand and I see that her fingernails are painted a pearly pink.

She tilts her head against the door and laughs. Her thick curls swarm. I could bite her exposed neck. I do not want to get caught, sent home. I see my father’s hand raised up to hit me and know I’m about to step off a great ledge. In a panic I reach for the doorknob, startling Aviva. I open the door carefully, listen to the stairs and hallways. “It’s all right,” she says, although how can she know this? But she happens to be correct. There’s the oddest emptiness and silence as if these moments and this place were set aside just for us amid the busyness of moving-in day at the Academy. Aviva gives the door a bump with her ass to shut it again, but I insert myself into the opening and slide past her, fleeing down the stairs and out into Hiram’s yard.

Cort and Voss are no longer sitting on the bench in front of Weld. A lone bicycle is chained to its arm.

Later I see Voss in the common room reading a New Gods comic book. “How was the chick?” he asks. I shrug. Big nose, I say. Too much makeup. Not my type.