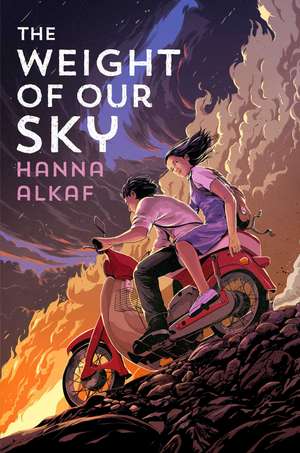

The Weight of Our Sky

Autor Hanna Alkafen Limba Engleză Paperback – 27 mai 2021 – vârsta de la 12 ani

Melati Ahmad looks like your typical movie-going, Beatles-obsessed sixteen-year-old. Unlike most other sixteen-year-olds though, Mel also believes that she harbors a djinn inside her, one who threatens her with horrific images of her mother’s death unless she adheres to an elaborate ritual of counting and tapping to keep him satisfied.

A trip to the movies after school turns into a nightmare when the city erupts into violent race riots between the Chinese and the Malay. When gangsters come into the theater and hold movie-goers hostage, Mel, a Malay, is saved by a Chinese woman, but has to leave her best friend behind to die.

On their journey through town, Mel sees for herself the devastation caused by the riots. In her village, a neighbor tells her that her mother, a nurse, was called in to help with the many bodies piling up at the hospital. Mel must survive on her own, with the help of a few kind strangers, until she finds her mother. But the djinn in her mind threatens her ability to cope.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 46.41 lei 25-37 zile | +20.40 lei 4-10 zile |

| Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers – 27 mai 2021 | 46.41 lei 25-37 zile | +20.40 lei 4-10 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 111.33 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers – 20 feb 2019 | 111.33 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 46.41 lei

Preț vechi: 57.48 lei

-19% Nou

Puncte Express: 70

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.88€ • 9.22$ • 7.42£

8.88€ • 9.22$ • 7.42£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-12 martie

Livrare express 07-13 februarie pentru 30.39 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534426092

ISBN-10: 1534426094

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (no spfx)

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1534426094

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (no spfx)

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

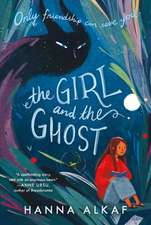

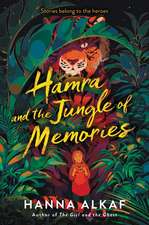

Hanna Alkaf is the author of The Weight of Our Sky, Queen of the Tiles, The Girl and the Ghost, Hamra and the Jungle of Memories, and The Hysterical Girls of St. Bernadette’s, as well as coeditor of the young adult anthology The Grimoire of Grave Fates. She graduated with a degree in journalism from Northwestern University and has spent most of her life working with words, both in fiction and nonfiction. She lives in Kuala Lumpur with her family.

Extras

The Weight of Our Sky

BY THE TIME SCHOOL ENDS on Tuesday, my mother has died seventeen times.

On the way to school, she is run over by a runaway lorry, her insides smeared across the black tar road like so much strawberry jelly. During English, while we recite a poem to remember our parts of speech (“An interjection cries out HARK! I need an EXCLAMATION MARK!” our teacher Mrs. Lalitha declaims, gesturing for us to follow, pulling the most dramatic faces), she is caught in a cross fire between police and gang members and is killed by a stray bullet straight through her chest, blood blossoming in delicate blooms all over her crisp white nurse’s uniform. At recess, she accidentally ingests some sort of dire poison and dies screaming in agony, her face purple, the corners of her open mouth flecked with white foam and spittle. And as we peruse our geography textbooks, my mother is stabbed repeatedly by robbers, the wicked blades of their parangs gliding through her flesh as though it were butter.

I know the signs; this is the Djinn, unfolding himself, stretching out, pricking me gently with his clawed fingers. See what I can do? he whispers, unfurling yet another death scene in all its technicolor glory. See what happens when you disobey? They float to the top of my consciousness unbidden at the most random times and set off a chain reaction throughout my entire body: cold sweat, damp palms, racing heart, nausea, light-headedness, the sensation of a thousand needles pricking me from head to toe.

It seems difficult now to believe that there was ever a time when the only djinns I believed in came from fairy tales, benevolent creatures that poured like smoke from humble old oil lamps and antique rings, granted you your heart’s desire, then disappeared when the transaction was complete. I might even have daydreamed of finding one someday. And later, they took a different shape, one informed by religious teachers and Quran recitation classes: creatures of smoke and fire, who had their own realm on Earth and kept to themselves, for the most part.

I didn’t realize they could be sharp, cruel, insidious little things that crept and wormed their way into your thoughts and made your brain hot and itchy.

The clanging of the final bell echoes through the school corridors. “Te-ri-ma-ka-sih-cik-gu.” The class singsongs their thank-yous in unison as Mrs. Lim nods and strides briskly out the door in her severe, high-necked navy-blue dress, the blackboard covered in complicated mathematical formulas, the floor before it covered in chalk dust. I stuff my books hurriedly into my bag, smiling halfheartedly and waving as other girls pass—“Bye, Mel!” “See you tomorrow!”—and I concentrate on the task at hand. Biggest to smallest, pencil case in the right-hand pocket, tap each item three times before closing the bag, one, two, three. Something feels off. My hands are frozen, suspended above my belongings. Did I do that right? Did I tap three times or four? I break out into a light sweat. Again, the Djinn whispers, again. Think how much better you’ll feel when you finally get it.

No, I tell him firmly, trying to ignore the way my fingers twitch, the wave of panic rising from my stomach.

Yes, he says.

One, two, three. One, two, three. One, two . . .

“Well?”

I look up, startled. My best friend, Safiyah, is standing by my desk, rocking back and forth eagerly on her heels, quivering with high excitement from the tips of her toes to the tip of her perfectly perky ponytail, tied back with a length of white ribbon. “Perfectly perky” is actually a great description of Saf in general, whom my mother often jokes only ever has two modes: “happy” and “asleep.” She bounces away through her days, dispensing ready smiles, compliments, and high fives to all and sundry, while I trail along in her wake, awkward, vaguely melancholy, and in a constant state of semi-embarrassment.

I’m pretty sure Saf is the reason I have friends at all.

“Well, what?”

Saf’s face falls. “Don’t tell me you forgot! You, me, Paul? Remember?”

“Oh, that.” My heart sinks. The last thing I want to do right now is be trapped in the dark, stuffy recesses of the neighborhood cinema as everyone else watches one movie and the Djinn forces me to watch another.

“Do we really have to, Saf?” I sling my bag over my shoulder and make for the door. One, two, three. One, two, three. One, two, three. There is a very specific pattern to adhere to, a rhythm that’s smooth and soothing, like the waltzes Mama likes to listen to on the radio on Sunday afternoons. A method to the madness.

Not that this is madness. It’s the Djinn.

“Of course we do!” Saf scurries along beside me, taking two steps for every one of my strides. “You promised! And anyway, I always back you up when it’s something to do with your Paul. . . .”

“You leave Paul McCartney out of this.” Right foot first out the door—good. “Or any of the Beatles, for that matter,” I add as an afterthought. I mean, I’m a little iffy about Ringo, but even he’s better than Paul Newman.

One, two, three. One, two, three. One, two, three.

“Come on, Mel, please. . . .” Her tone is wheedling now. “You know it has to be today. My dad’s at some kind of meeting until late. He’ll never let me go otherwise. You know how he feels about movies.” She screws up her face and lowers her voice in a dead-on imitation of her father. “?‘Movies? Movies DULL the mind, Safiyah. They are the refuge of the UNCULTURED and the UNEDUCATED. They erode your MORALS.’?”

I snort with laughter in spite of myself. “Fine,” I say grudgingly. “It’s not like Mama expects me at home anyway; she’s on shift at the hospital until tonight. But can’t we go to Cathay or Pavilion? At least they aren’t so far. We could just walk.”

Saf shakes her head firmly. “The Rex,” she says. “We have to go to the Rex.”

I shoot her a glance. “This wouldn’t have anything to do with the fact that Jason’s father’s sugarcane stall happens to be right across the street from there, right?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Saf says innocently, playing with the frayed end of her hair ribbon and doing her best not to look at me, a blush spreading like wildfire across her dimpled cheeks. “I just . . . really happen to prefer watching movies at the Rex.” I can’t help but grin. Saf can fool a lot of people with those good-girl looks and that demure smile. But then again most people haven’t been friends with her since the age of seven, when she marched right up to me on the first day of primary school, while everyone else stood around looking nervous and unsure, and declared cheerfully, “I like you! Let’s be best friends.” On the surface, we’re polar opposites: She is bright where I am dim, cheery smiles where I am worried frowns, pleasing plumpness where I am sharp, uncomfortable angles. But maybe that’s why we fit together so perfectly.

“You are so obvious,” I snigger, jabbing her in the ribs, and we dissolve into giggles as we run for the bus.

I hoist myself up the steps—right foot first: good girl, Mel—and the Djinn suddenly rears up, ready and alert. I feel a sickening weight in my stomach. The right-hand window seat in the third row, my usual choice—the safest choice—is occupied. A Chinese auntie, her loose short-sleeved blouse boasting dark patches of sweat, dozes in the afternoon heat. Whenever she leans too far forward, she quickly jerks her head back, her eyes opening for a split second, her face rearranging itself into something resembling propriety. But before long, she’s nodding off again, lulled by the gentle rolling of the bus.

I can feel the panic start to descend, that telltale prickling starting in my toes and working its way up to claim the rest of me. If you don’t sit in that seat, the safe seat, Mama will die, the Djinn whispers, and I hate how familiar his voice is to my ears, that low, rich rasp like gravel wrapped in velvet. Mama will die, and it’ll be all your fault.

I know it doesn’t make sense. I know it shouldn’t matter. But at the same time, I am absolutely certain that nothing matters more than this, not a single thing in the entire world. My chest heaves, up and down, up and down.

Quickly, I slide into the window seat on the left—still third row, which is good, but on the left, which is most definitely, terribly, awfully not good. But I can make it right. I can make it safe.

The old blue bus coughs and wheezes its way down the road and as Saf waxes lyrical about the dreamy swoop of Paul Newman’s perfect hair and the heavenly blue of his perfect eyes, my mother is floating, floating, floating down into the depths of the Klang River, her face blue, her eyes shut, her lungs filled with murky water.

Quickly, quietly, so that Saf won’t notice, I tap my right foot, then my left, then right again, thirty-three sets of three altogether, all the way to Petaling Street.

Finally, the Djinn subsides. For now.

CHAPTER ONE

BY THE TIME SCHOOL ENDS on Tuesday, my mother has died seventeen times.

On the way to school, she is run over by a runaway lorry, her insides smeared across the black tar road like so much strawberry jelly. During English, while we recite a poem to remember our parts of speech (“An interjection cries out HARK! I need an EXCLAMATION MARK!” our teacher Mrs. Lalitha declaims, gesturing for us to follow, pulling the most dramatic faces), she is caught in a cross fire between police and gang members and is killed by a stray bullet straight through her chest, blood blossoming in delicate blooms all over her crisp white nurse’s uniform. At recess, she accidentally ingests some sort of dire poison and dies screaming in agony, her face purple, the corners of her open mouth flecked with white foam and spittle. And as we peruse our geography textbooks, my mother is stabbed repeatedly by robbers, the wicked blades of their parangs gliding through her flesh as though it were butter.

I know the signs; this is the Djinn, unfolding himself, stretching out, pricking me gently with his clawed fingers. See what I can do? he whispers, unfurling yet another death scene in all its technicolor glory. See what happens when you disobey? They float to the top of my consciousness unbidden at the most random times and set off a chain reaction throughout my entire body: cold sweat, damp palms, racing heart, nausea, light-headedness, the sensation of a thousand needles pricking me from head to toe.

It seems difficult now to believe that there was ever a time when the only djinns I believed in came from fairy tales, benevolent creatures that poured like smoke from humble old oil lamps and antique rings, granted you your heart’s desire, then disappeared when the transaction was complete. I might even have daydreamed of finding one someday. And later, they took a different shape, one informed by religious teachers and Quran recitation classes: creatures of smoke and fire, who had their own realm on Earth and kept to themselves, for the most part.

I didn’t realize they could be sharp, cruel, insidious little things that crept and wormed their way into your thoughts and made your brain hot and itchy.

The clanging of the final bell echoes through the school corridors. “Te-ri-ma-ka-sih-cik-gu.” The class singsongs their thank-yous in unison as Mrs. Lim nods and strides briskly out the door in her severe, high-necked navy-blue dress, the blackboard covered in complicated mathematical formulas, the floor before it covered in chalk dust. I stuff my books hurriedly into my bag, smiling halfheartedly and waving as other girls pass—“Bye, Mel!” “See you tomorrow!”—and I concentrate on the task at hand. Biggest to smallest, pencil case in the right-hand pocket, tap each item three times before closing the bag, one, two, three. Something feels off. My hands are frozen, suspended above my belongings. Did I do that right? Did I tap three times or four? I break out into a light sweat. Again, the Djinn whispers, again. Think how much better you’ll feel when you finally get it.

No, I tell him firmly, trying to ignore the way my fingers twitch, the wave of panic rising from my stomach.

Yes, he says.

One, two, three. One, two, three. One, two . . .

“Well?”

I look up, startled. My best friend, Safiyah, is standing by my desk, rocking back and forth eagerly on her heels, quivering with high excitement from the tips of her toes to the tip of her perfectly perky ponytail, tied back with a length of white ribbon. “Perfectly perky” is actually a great description of Saf in general, whom my mother often jokes only ever has two modes: “happy” and “asleep.” She bounces away through her days, dispensing ready smiles, compliments, and high fives to all and sundry, while I trail along in her wake, awkward, vaguely melancholy, and in a constant state of semi-embarrassment.

I’m pretty sure Saf is the reason I have friends at all.

“Well, what?”

Saf’s face falls. “Don’t tell me you forgot! You, me, Paul? Remember?”

“Oh, that.” My heart sinks. The last thing I want to do right now is be trapped in the dark, stuffy recesses of the neighborhood cinema as everyone else watches one movie and the Djinn forces me to watch another.

“Do we really have to, Saf?” I sling my bag over my shoulder and make for the door. One, two, three. One, two, three. One, two, three. There is a very specific pattern to adhere to, a rhythm that’s smooth and soothing, like the waltzes Mama likes to listen to on the radio on Sunday afternoons. A method to the madness.

Not that this is madness. It’s the Djinn.

“Of course we do!” Saf scurries along beside me, taking two steps for every one of my strides. “You promised! And anyway, I always back you up when it’s something to do with your Paul. . . .”

“You leave Paul McCartney out of this.” Right foot first out the door—good. “Or any of the Beatles, for that matter,” I add as an afterthought. I mean, I’m a little iffy about Ringo, but even he’s better than Paul Newman.

One, two, three. One, two, three. One, two, three.

“Come on, Mel, please. . . .” Her tone is wheedling now. “You know it has to be today. My dad’s at some kind of meeting until late. He’ll never let me go otherwise. You know how he feels about movies.” She screws up her face and lowers her voice in a dead-on imitation of her father. “?‘Movies? Movies DULL the mind, Safiyah. They are the refuge of the UNCULTURED and the UNEDUCATED. They erode your MORALS.’?”

I snort with laughter in spite of myself. “Fine,” I say grudgingly. “It’s not like Mama expects me at home anyway; she’s on shift at the hospital until tonight. But can’t we go to Cathay or Pavilion? At least they aren’t so far. We could just walk.”

Saf shakes her head firmly. “The Rex,” she says. “We have to go to the Rex.”

I shoot her a glance. “This wouldn’t have anything to do with the fact that Jason’s father’s sugarcane stall happens to be right across the street from there, right?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Saf says innocently, playing with the frayed end of her hair ribbon and doing her best not to look at me, a blush spreading like wildfire across her dimpled cheeks. “I just . . . really happen to prefer watching movies at the Rex.” I can’t help but grin. Saf can fool a lot of people with those good-girl looks and that demure smile. But then again most people haven’t been friends with her since the age of seven, when she marched right up to me on the first day of primary school, while everyone else stood around looking nervous and unsure, and declared cheerfully, “I like you! Let’s be best friends.” On the surface, we’re polar opposites: She is bright where I am dim, cheery smiles where I am worried frowns, pleasing plumpness where I am sharp, uncomfortable angles. But maybe that’s why we fit together so perfectly.

“You are so obvious,” I snigger, jabbing her in the ribs, and we dissolve into giggles as we run for the bus.

I hoist myself up the steps—right foot first: good girl, Mel—and the Djinn suddenly rears up, ready and alert. I feel a sickening weight in my stomach. The right-hand window seat in the third row, my usual choice—the safest choice—is occupied. A Chinese auntie, her loose short-sleeved blouse boasting dark patches of sweat, dozes in the afternoon heat. Whenever she leans too far forward, she quickly jerks her head back, her eyes opening for a split second, her face rearranging itself into something resembling propriety. But before long, she’s nodding off again, lulled by the gentle rolling of the bus.

I can feel the panic start to descend, that telltale prickling starting in my toes and working its way up to claim the rest of me. If you don’t sit in that seat, the safe seat, Mama will die, the Djinn whispers, and I hate how familiar his voice is to my ears, that low, rich rasp like gravel wrapped in velvet. Mama will die, and it’ll be all your fault.

I know it doesn’t make sense. I know it shouldn’t matter. But at the same time, I am absolutely certain that nothing matters more than this, not a single thing in the entire world. My chest heaves, up and down, up and down.

Quickly, I slide into the window seat on the left—still third row, which is good, but on the left, which is most definitely, terribly, awfully not good. But I can make it right. I can make it safe.

The old blue bus coughs and wheezes its way down the road and as Saf waxes lyrical about the dreamy swoop of Paul Newman’s perfect hair and the heavenly blue of his perfect eyes, my mother is floating, floating, floating down into the depths of the Klang River, her face blue, her eyes shut, her lungs filled with murky water.

Quickly, quietly, so that Saf won’t notice, I tap my right foot, then my left, then right again, thirty-three sets of three altogether, all the way to Petaling Street.

Finally, the Djinn subsides. For now.

Recenzii

This stunning debut from Malaysian author Alkaf filters Melati’s sympathetic internal narrative through a mental illness barely understood and poorly treated for the era, and the setting and secondary characters convey a visceral, nerve-wracking moment in time. This isn’t an easy story by far; an author’s note warns of “graphic violence, death, racism, OCD, and anxiety triggers”—but their inclusion makes it no less essential, no less unforgettable.

This is a brutally honest, no-holds-barred reimagining of the time: The evocative voice transports readers to 1960s Malaysia, and the brisk pace is enthralling. Above all, the raw emotion splashed across the pages will resonate deeply, no matter one's race or religion. Unabashedly rooted in the author's homeland and confronting timely topics and challenging themes, this book has broad appeal for teen readers.

At the sentence level, Alkaf’s use of first-person narration expertly (and, in some cases, painfully) places readers inside Melati’s head as she experiences internal and external horrors....Echoing contemporary race relations, the subject feels especially relevant. VERDICT Alkaf’s immersive, powerful writing make this a must-purchase for all YA collections.

With her debut young adult novel, The Weight of Our Sky, journalist Hanna Alkaf provides heart-pounding, graphic insight into the seismic life shifts experienced by residents of Kuala Lumpur in the days directly following the May 1969 Malaysian Riots.

Alkaf offers a gripping fictionalized account of the 1969 post-election riots in Malaysia, limning acts of bravery and tolerance that unreel alongside the slaughter perpetrated in the Kuala Lumpur streets.

Melati’s growing strength gives hope to readers: If she can fight her inner demon and save the day, then they can, too.

This is a brutally honest, no-holds-barred reimagining of the time: The evocative voice transports readers to 1960s Malaysia, and the brisk pace is enthralling. Above all, the raw emotion splashed across the pages will resonate deeply, no matter one's race or religion. Unabashedly rooted in the author's homeland and confronting timely topics and challenging themes, this book has broad appeal for teen readers.

At the sentence level, Alkaf’s use of first-person narration expertly (and, in some cases, painfully) places readers inside Melati’s head as she experiences internal and external horrors....Echoing contemporary race relations, the subject feels especially relevant. VERDICT Alkaf’s immersive, powerful writing make this a must-purchase for all YA collections.

With her debut young adult novel, The Weight of Our Sky, journalist Hanna Alkaf provides heart-pounding, graphic insight into the seismic life shifts experienced by residents of Kuala Lumpur in the days directly following the May 1969 Malaysian Riots.

Alkaf offers a gripping fictionalized account of the 1969 post-election riots in Malaysia, limning acts of bravery and tolerance that unreel alongside the slaughter perpetrated in the Kuala Lumpur streets.

Melati’s growing strength gives hope to readers: If she can fight her inner demon and save the day, then they can, too.

Descriere

A music loving teen with OCD does everything she can to find her way back to her mother during the historic race riots in 1969 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in this heart-pounding debut.