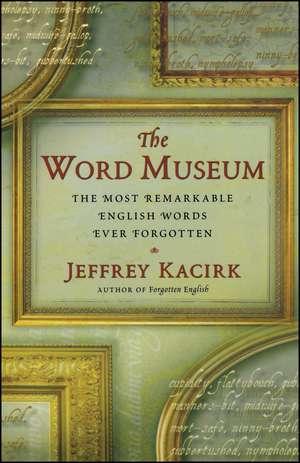

The Word Museum: The Most Remarkable English Words Ever Forgotten

Autor Jeffrey Kacirken Limba Engleză Paperback – 15 ian 2001

Preț: 97.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 146

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.65€ • 19.52$ • 15.47£

18.65€ • 19.52$ • 15.47£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 19 martie-02 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780684857619

ISBN-10: 0684857618

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 40-50 line illustrations t-o

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0684857618

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 40-50 line illustrations t-o

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Jeffrey Kacirk is the author of Forgotten English, The Word Museum, and Altered English, as well as a daily calendar based on Forgotten English. He can be found on the web at www.forgottenenglish.com and lives in Marin County, California.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

The English language, as the largest and most dynamic collection of words and phrases ever assembled, continues to expand, absorbing hundreds of words annually into its official and unofficial rolls, but not without a simultaneous yet imperceptible sacrifice of terms along the way. Fortunately, before their quiet disappearance, many of these reflections of antiquity, the "remnants of history which casually escaped the shipwreck of time," to use a phrase of Francis Bacon, were recorded in a variety of published and unpublished writings, including dictionaries and glossaries.

I still remember my first browse through one of these nineteenth-century lexicons, in which I failed to find a noteworthy entry for some time. Coupled with my initial enchantment was a bit of discouragement brought on by the sheer volume of words that had changed surprisingly little over a century and a half. But a few years later, I found renewed inspiration in Joseph Shipley's Dictionary of Early English, a work densely packed with intriguing vignettes of bygone eras. As I located more of this type of historical reference, I began to realize that, despite their undeniable dusty-dryness, these yellowed time capsules could provide intimate glimpses of the past, while charting the evolution of English. Sensing the story that these archaisms had to tell, I began to compile a notebook of my favorites, and eventually developed the goal of organizing these gems into a form that would allow others to conveniently sample a diverse cross section of the best lexicographers without undue tedium.

Of particular interest to me have been the myriad elusive details of earlier times that tend to go unnoticed. In my schooling, I found that teachers and historians, because of their socially prescribed curricular attention toward larger social concepts, often bypassed the smaller and more personal expressions of social custom and conduct, often leaving the novel as the best lens with which to view forgotten elements of everyday life. Take, for instance, the long-defunct activity called upknocking, the employment of the knocker up, who went house to house in the early morning hours of the nineteenth century to awaken his working-class clients before the advent of affordable alarm clocks. Until encountering this entry, I had never thought about how people of this time managed to awaken with any predictability.

In putting together this retrospective, I was reminded many times of Charles Mackay, who in the introduction to his 1874 glossary, Lost Beauties of the English Language, appealed to his readers, and especially to writers and poets, to consider resurrecting some of the more colorful but obscure words he had highlighted, by using them in place of their drab modern counterparts. Mackay's work is characteristic of a largely nineteenth-century movement to record fading provincial and archaic language, an activity that was perceived to be necessary in part because of the culturally homogenizing influence of the expanding railroad on formerly isolated communities. This surge of interest among both amateur and professional wordsmiths in the British Isles involved the gathering and publication of terms not for their practical application in vocabulary building but because they were recognized as being of historical interest in their own right.

I based my selection of entries for The Word Museum on a number of subjective considerations, an important one being the "Jabberwocky factor" -- the eccentric phonic essence of certain headwords, such as crulge, gubbertushed, and kiddliwink. As a tandem goal of mine was to spotlight endearing, rough-hewn, and humorous aspects of Old World life, other formerly plausible terms, such as idle-worms, blink-fencer, and pastorauling, were also selected. Many of these linguistic fossils are remarkable for their longevity, while others delight us because they describe persistent anachronisms, such as stang, an ancient vigilante-style chastisement for marital infidelity, which managed to survive into the twentieth century. Specifically, my bias has been in favor of expressions that not only offer insights into the nature of our living language but simultaneously illustrate telltale beliefs and customs.

In singling out material for this project, I passed over nearly all commonly understood standard English words, along with place-names and the bulk of the vocabulary from the realm of the naturalist, including the names of plants, animals, minerals, and chemical compounds, except for such noteworthy exceptions as goatmilker. I discarded the names of nearly every type of hardware, despite their sometimes curious meanings, along with almost all foreignisms, which, it might be argued, are often not particularly English anyway. The reader will, however, find a sampling of scientific-sounding Greek- and Latin-based words, like nympholepsy, pornocracy, and ambidexter, which were once known figuratively as inkhorn terms because of their origins in the ink holders of pedantic writers.

When similar or identical entries were found in multiple sources, I presented the best written, most revealing, or oldest descriptions. When an entry was found in a source, such as Wright's Dialect Dictionary, that credited an older one, I generally credited the earlier source. At times I included more than one etymological explanation to add depth to definitions, to allow the reader to decide which might be correct, and to give a sense of how subjective etymology can be. It should be noted that, particularly with regional words, reader familiarity with some entries is inevitable, as my intention was to put forth the most interesting expressions, not necessarily those that have disappeared completely.

Peppered throughout this work is an odd group of once common adjectives, adverbs, and abstract nouns that, while similar to modern words, look and sound strange to us today, such as ruly, anywhen, and thrunched. Certainly these abandoned forms once rolled off the tongue and into the ear without the perceptual thud they might convey to the sensibilities of many modern readers and listeners. A few of these seemed worth shedding light on because they illustrate an informal rule of thumb: modern words and phrases often sound less awkward than their archaic forerunners, which is somewhat akin to the proverb "History is written by the victors."

I gently reconstructed a small minority of definitions solely for the sake of clarity, brevity, and overall readability, yet I made every attempt to retain the integrity and charm of the original passages. Where unavoidable, I took the liberty of modernizing our linguistic ancestors' creative spelling and distinctive punctuation, added bracketed words of explanation, and in a few instances combined noncontiguous sentences by one author into a single, comprehensive description. These changes were often necessary to ensure not only the reader's understanding of an entry but the entry's ability to fit the format.

Author citations, found after each quotation, refer the reader to the bibliography. The dates of publication found there should be viewed as merely a clue to when a given expression was in effect. Most words were used at the time of publication listed, but it should be kept in mind that an entry's usage may well have occurred somewhat or much earlier (as in the glossaries of Shakespeare) and some entries may have remained current well beyond this date, even into modern times.

As important as it may be to examine the early cataloguers of English, my focus has been on showcasing the terms themselves. Nonetheless, an understanding of the lives and individual contributions of certain lexicographers can greatly enhance our appreciation of the formation of modern English. For an in-depth examination of the minds behind the dictionaries, I recommend Jonathon Green's 1996 work, Chasing the Sun, for its well-researched character sketches of prominent dictionary makers and their craft.

Although we are inevitably left with a less than complete profile of many of these abandoned expressions, their remains can kindle in us a sense of wonder about the development of not only the English language but, by extension, many Western social traditions. I hope that these remarkable philological relics, by offering a peep through a fence knothole at vanished times and modes of expression, will provide the reader heartfelt connections with the mystery-laden past.

Copyright © 2000 by Jeffrey Kacirk

The English language, as the largest and most dynamic collection of words and phrases ever assembled, continues to expand, absorbing hundreds of words annually into its official and unofficial rolls, but not without a simultaneous yet imperceptible sacrifice of terms along the way. Fortunately, before their quiet disappearance, many of these reflections of antiquity, the "remnants of history which casually escaped the shipwreck of time," to use a phrase of Francis Bacon, were recorded in a variety of published and unpublished writings, including dictionaries and glossaries.

I still remember my first browse through one of these nineteenth-century lexicons, in which I failed to find a noteworthy entry for some time. Coupled with my initial enchantment was a bit of discouragement brought on by the sheer volume of words that had changed surprisingly little over a century and a half. But a few years later, I found renewed inspiration in Joseph Shipley's Dictionary of Early English, a work densely packed with intriguing vignettes of bygone eras. As I located more of this type of historical reference, I began to realize that, despite their undeniable dusty-dryness, these yellowed time capsules could provide intimate glimpses of the past, while charting the evolution of English. Sensing the story that these archaisms had to tell, I began to compile a notebook of my favorites, and eventually developed the goal of organizing these gems into a form that would allow others to conveniently sample a diverse cross section of the best lexicographers without undue tedium.

Of particular interest to me have been the myriad elusive details of earlier times that tend to go unnoticed. In my schooling, I found that teachers and historians, because of their socially prescribed curricular attention toward larger social concepts, often bypassed the smaller and more personal expressions of social custom and conduct, often leaving the novel as the best lens with which to view forgotten elements of everyday life. Take, for instance, the long-defunct activity called upknocking, the employment of the knocker up, who went house to house in the early morning hours of the nineteenth century to awaken his working-class clients before the advent of affordable alarm clocks. Until encountering this entry, I had never thought about how people of this time managed to awaken with any predictability.

In putting together this retrospective, I was reminded many times of Charles Mackay, who in the introduction to his 1874 glossary, Lost Beauties of the English Language, appealed to his readers, and especially to writers and poets, to consider resurrecting some of the more colorful but obscure words he had highlighted, by using them in place of their drab modern counterparts. Mackay's work is characteristic of a largely nineteenth-century movement to record fading provincial and archaic language, an activity that was perceived to be necessary in part because of the culturally homogenizing influence of the expanding railroad on formerly isolated communities. This surge of interest among both amateur and professional wordsmiths in the British Isles involved the gathering and publication of terms not for their practical application in vocabulary building but because they were recognized as being of historical interest in their own right.

I based my selection of entries for The Word Museum on a number of subjective considerations, an important one being the "Jabberwocky factor" -- the eccentric phonic essence of certain headwords, such as crulge, gubbertushed, and kiddliwink. As a tandem goal of mine was to spotlight endearing, rough-hewn, and humorous aspects of Old World life, other formerly plausible terms, such as idle-worms, blink-fencer, and pastorauling, were also selected. Many of these linguistic fossils are remarkable for their longevity, while others delight us because they describe persistent anachronisms, such as stang, an ancient vigilante-style chastisement for marital infidelity, which managed to survive into the twentieth century. Specifically, my bias has been in favor of expressions that not only offer insights into the nature of our living language but simultaneously illustrate telltale beliefs and customs.

In singling out material for this project, I passed over nearly all commonly understood standard English words, along with place-names and the bulk of the vocabulary from the realm of the naturalist, including the names of plants, animals, minerals, and chemical compounds, except for such noteworthy exceptions as goatmilker. I discarded the names of nearly every type of hardware, despite their sometimes curious meanings, along with almost all foreignisms, which, it might be argued, are often not particularly English anyway. The reader will, however, find a sampling of scientific-sounding Greek- and Latin-based words, like nympholepsy, pornocracy, and ambidexter, which were once known figuratively as inkhorn terms because of their origins in the ink holders of pedantic writers.

When similar or identical entries were found in multiple sources, I presented the best written, most revealing, or oldest descriptions. When an entry was found in a source, such as Wright's Dialect Dictionary, that credited an older one, I generally credited the earlier source. At times I included more than one etymological explanation to add depth to definitions, to allow the reader to decide which might be correct, and to give a sense of how subjective etymology can be. It should be noted that, particularly with regional words, reader familiarity with some entries is inevitable, as my intention was to put forth the most interesting expressions, not necessarily those that have disappeared completely.

Peppered throughout this work is an odd group of once common adjectives, adverbs, and abstract nouns that, while similar to modern words, look and sound strange to us today, such as ruly, anywhen, and thrunched. Certainly these abandoned forms once rolled off the tongue and into the ear without the perceptual thud they might convey to the sensibilities of many modern readers and listeners. A few of these seemed worth shedding light on because they illustrate an informal rule of thumb: modern words and phrases often sound less awkward than their archaic forerunners, which is somewhat akin to the proverb "History is written by the victors."

I gently reconstructed a small minority of definitions solely for the sake of clarity, brevity, and overall readability, yet I made every attempt to retain the integrity and charm of the original passages. Where unavoidable, I took the liberty of modernizing our linguistic ancestors' creative spelling and distinctive punctuation, added bracketed words of explanation, and in a few instances combined noncontiguous sentences by one author into a single, comprehensive description. These changes were often necessary to ensure not only the reader's understanding of an entry but the entry's ability to fit the format.

Author citations, found after each quotation, refer the reader to the bibliography. The dates of publication found there should be viewed as merely a clue to when a given expression was in effect. Most words were used at the time of publication listed, but it should be kept in mind that an entry's usage may well have occurred somewhat or much earlier (as in the glossaries of Shakespeare) and some entries may have remained current well beyond this date, even into modern times.

As important as it may be to examine the early cataloguers of English, my focus has been on showcasing the terms themselves. Nonetheless, an understanding of the lives and individual contributions of certain lexicographers can greatly enhance our appreciation of the formation of modern English. For an in-depth examination of the minds behind the dictionaries, I recommend Jonathon Green's 1996 work, Chasing the Sun, for its well-researched character sketches of prominent dictionary makers and their craft.

Although we are inevitably left with a less than complete profile of many of these abandoned expressions, their remains can kindle in us a sense of wonder about the development of not only the English language but, by extension, many Western social traditions. I hope that these remarkable philological relics, by offering a peep through a fence knothole at vanished times and modes of expression, will provide the reader heartfelt connections with the mystery-laden past.

Copyright © 2000 by Jeffrey Kacirk

Recenzii

Richard Lederer author of Crazy English Through the wabe of The Word Museum gyre and gimble some of the most abracadabrant creations of our word-bethumped English language. You'll be a more verbivorous human being after you take this tour.

Barbara Wallraff author of Word Court What fun The Word Museum is. It is a bouffage -- an absolute yeepsen -- for word-peckers, and that's no scaum.

Justin Kaplan and Anne Bernays authors of The Language of Names It's an absolutely delicious book, a ten-course banquet for anyone with an appetite for words, dictionary games, and just plain fun.

Barbara Wallraff author of Word Court What fun The Word Museum is. It is a bouffage -- an absolute yeepsen -- for word-peckers, and that's no scaum.

Justin Kaplan and Anne Bernays authors of The Language of Names It's an absolutely delicious book, a ten-course banquet for anyone with an appetite for words, dictionary games, and just plain fun.

Descriere

A witty and whimsical A to Z gallery of entertaining vintage expressions from the English language.