Thief Of Time

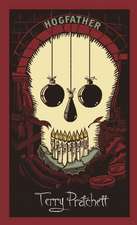

Autor Terry Pratchetten Limba Engleză Hardback – 19 oct 2017

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (4) | 54.97 lei 21-33 zile | +22.11 lei 7-13 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – 27 oct 2022 | 54.97 lei 21-33 zile | +22.11 lei 7-13 zile |

| HarperCollins Publishers – 28 iul 2014 | 58.72 lei 3-5 săpt. | +19.90 lei 7-13 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – 10 oct 2013 | 59.98 lei 21-33 zile | +23.52 lei 7-13 zile |

| Harpercollins – 11 mar 2025 | 98.73 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 82.78 lei 21-33 zile | +33.70 lei 7-13 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – 19 oct 2017 | 82.78 lei 21-33 zile | +33.70 lei 7-13 zile |

Preț: 82.78 lei

Preț vechi: 96.92 lei

-15% Nou

Puncte Express: 124

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.84€ • 16.54$ • 13.11£

15.84€ • 16.54$ • 13.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-26 martie

Livrare express 28 februarie-06 martie pentru 43.69 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780857525031

ISBN-10: 0857525034

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

ISBN-10: 0857525034

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Notă biografică

TERRY PRATCHETT is the acclaimed creator of the global bestselling Discworld series, the first of which, The Colour of Magic, was published in 1983. In all, he is the author of over fifty bestselling books. His novels have been widely adapted for stage and screen, and he is the winner of multiple prizes, including the Carnegie Medal, as well as being awarded a knighthood for services to literature. Worldwide sales of his books now stand at over 75 million, and they have been translated into thirty-seven languages.

Extras

According to the First Scroll of Wen the Eternally Surprised, Wen stepped out of the cave where he had received enlightenment and into the dawning light of the first day of the rest of his life. He stared at the rising sun for some time, because he had never seen it before.

He prodded with a sandal the dozing form of Clodpool the apprentice, and said: 'I have seen. Now I understand.'

Then he stopped, and looked at the thing next to Clodpool.

'What is that amazing thing?' he said.

'Er . . . er . . . it's a tree, master,' said Clodpool, still not quite awake. 'Remember? It was there yesterday.'

'There was no yesterday.'

'Er . . . er . . . I think there was, master,' said Clodpool, struggling to his feet. 'Remember? We came up here and I cooked a meal, and had the rind off your sklang because you didn't want it.'

'I remember yesterday,' said Wen thoughtfully. 'But the memory is in my head now. Was yesterday real? Or is it only the memory that is real? Truly, yesterday I was not born.'

Clodpool's face became a mask of agonized incomprehension.

'Dear stupid Clodpool, I have learned everything,' said Wen. 'In the cup of the hand there is no past, no future. There is only now. There is no time but the present. We have a great deal to do.'

Clodpool hesitated. There was something new about his master. There was a glow in his eyes and, when he moved, there were strange silvery-blue lights in the air, like reflections from liquid mirrors.

'She has told me everything,' Wen went on. 'I know that time was made for men, not the other way round. I have learned how to shape it and bend it. I know how to make a moment last for ever, because it already has. And I can teach these skills even to you, Clodpool. I have heard the heartbeat of the universe. I know the answers to many questions. Ask me.'

The apprentice gave him a bleary look. It was too early in the morning for it to be early in the morning. That was the only thing that he currently knew for sure.

'Er . . . what does master want for breakfast?' he said.

Wen looked down from their camp and across the snowfields and purple mountains to the golden daylight creating the world, and mused upon certain aspects of humanity.

'Ah,' he said. 'One of the difficult ones.'

For something to exist, it has to be observed.

For something to exist, it has to have a position in time and space.

And this explains why nine-tenths of the mass of the universe is unaccounted for.

Nine-tenths of the universe is the knowledge of the position and direction of everything in the other tenth. Every atom has its biography, every star its file, every chemical exchange its equivalent of the inspector with a clipboard. It is unaccounted for because it is doing the accounting for the rest of it, and you cannot see the back of your own head.*

Nine-tenths of the universe, in fact, is the paperwork.

And if you want the story, then remember that a story does not unwind. It weaves. Events that start in different places and different times all bear down on that one tiny point in space-time, which is the perfect moment.

Supposing an emperor was persuaded to wear a new suit of clothes whose material was so fine that, to the common eye, the clothes weren't there. And suppose a little boy pointed out this fact in a loud, clear voice . . .

Then you have The Story of the Emperor Who Had No Clothes.

But if you knew a bit more, it would be The Story of the Boy Who Got a Well-Deserved Thrashing from His Dad for Being Rude to Royalty, and Was Locked Up.

Or The Story of the Whole Crowd Who Were Rounded Up by the Guards and Told 'This Didn't Happen, Okay? Does Anyone Want to Argue?'

Or it could be a story of how a whole kingdom suddenly saw the benefits of the 'new clothes', and developed an enthusiasm for healthy sports* in a lively and refreshing atmosphere which got many new adherents every year, and led to a recession caused by the collapse of the conventional clothing industry.

It could even be a story about The Great Pneumonia Epidemic of '09.

It all depends on how much you know.

Supposing you'd watched the slow accretion of snow over thousands of years as it was compressed and pushed over the deep rock until the glacier calved its icebergs into the sea, and you watched an iceberg drift out through the chilly waters, and you got to know its cargo of happy polar bears and seals as they looked forward to a brave new life in the other hemisphere where they say the ice floes are lined with crunchy penguins, and then wham! Tragedy loomed in the shape of thousands of tons of unaccountably floating iron and an exciting soundtrack . . .

. . . you'd want to know the whole story.

And this one starts with desks.

This is the desk of a professional. It is clear that their job is their life. There are . . . human touches, but these are the human touches that strict usage allows in a chilly world of duty and routine.

Mostly they're on the only piece of real colour in this picture of blacks and greys. It's a coffee mug. Someone somewhere wanted to make it a jolly mug. It bears a rather unconvincing picture of a teddy bear, and the legend 'To The World's Greatest Grandad' and the slight change in the style of lettering on the word 'Grandad' makes it clear that this has come from one of those stalls that have hundreds of mugs like this, declaring that they're for the world's greatest Grandad/Dad/Mum/Granny/Uncle/Aunt/Blank. Only someone whose life contains very little else, one feels, would treasure a piece of gimcrackery like this.

It currently holds tea, with a slice of lemon.

The bleak desktop also contains a paperknife in the shape of a scythe and a number of hourglasses.

Death picks up the mug in a skeletal hand . . .

. . . and took a sip, pausing only to look again at the wording he'd read thousands of times before, and then put it down.

very well, he said, in tones of funeral bells. show me.

The last item on the desktop was a mechanical contrivance. 'Contrivance' was exactly the right kind of word for it. Most of it was two discs. One was horizontal and contained a circlet of very small squares of what would prove to be carpet. The other was set vertically and had a large number of arms, each one of which held a very small slice of buttered toast. Each slice was set so that it could spin freely as the turning of the wheel brought it down towards the carpet disc.

I believe I am beginning to get the idea, said Death.

The small figure by the machine saluted smartly and beamed, if a rat skull could beam. It pulled a pair of goggles over its eye sockets, hitched up its robe and clambered into the machine.

Death was never quite sure why he allowed the Death of Rats to have an independent existence. After all, being Death meant being the Death of everything, including rodents of all descriptions. But perhaps everyone needs a tiny part of themselves that can, metaphorically, be allowed to run naked in the rain*, to think the unthinkable thoughts, to hide in corners and spy on the world, to do the forbidden but enjoyable deeds.

Slowly, the Death of Rats pushed the treadles. The wheels began to spin.

'Exciting, eh?' said a hoarse voice by Death's ear. It belonged to Quoth, the raven, who had attached himself to the household as the Death of Rats' personal transport and crony. He was, he always said, only in it for the eyeballs.

The carpets began to turn. The tiny toasties slapped down randomly, sometimes with a buttery squelch, sometimes without. Quoth watched carefully, in case any eyeballs were involved.

Death saw that some time and effort had been spent devising a mechanism to rebutter each returning slice. An even more complex one measured the number of buttered carpets.

After a couple of complete turns the lever of the buttered carpet ratio device had moved to 60 per cent, and the wheels stopped.

well? said Death. if you did it again, it could well be that-

The Death of Rats shifted a gear lever and began to pedal again.

squeak, it commanded. Death obediently leaned closer.

This time the needle went only as high as 40 per cent.

Death leaned closer still.

The eight pieces of carpet that had been buttered this time were, in their entirety, the pieces that had been missed first time round.

Spidery cogwheels whirred in the machine. A sign emerged, rather shakily, on springs, with an effect that was the visual equivalent of the word 'boing'.

A moment later two sparklers spluttered fitfully into life and sizzled away on either side of the word: MALIGNITY.

Death nodded. It was just as he'd suspected.

He crossed his study, the Death of Rats scampering ahead of him, and reached a full-length mirror. It was dark, like the bottom of a well. There was a pattern of skulls and bones around the frame, for the sake of appearances; Death could not look himself in the skull in a mirror with cherubs and roses around it.

The Death of Rats climbed the frame in a scrabble of claws and looked at Death expectantly from the top. Quoth fluttered over and pecked briefly at his own reflection, on the basis that anything was worth a try.

show me, said Death. show me . . . my thoughts.

A chessboard appeared, but it was triangular, and so big that only the nearest point could be seen. Right on this point was the world - turtle, elephants, the little orbiting sun and all. It was the Discworld, which existed only just this side of total improbability and, therefore, in border country. In border country the border gets crossed, and sometimes things creep into the universe that have rather more on their mind than a better life for their children and a wonderful future in the fruit-picking and domestic service industries.

On every other black or white triangle of the chessboard, all the way to infinity, was a small grey shape, rather like an empty hooded robe.

Why now? thought Death.

He recognized them. They were not life forms. They were . . . non-life forms. They were the observers of the operation of the universe, its clerks, its auditors. They saw to it that things spun and rocks fell.

And they believed that for a thing to exist it had to have a position in time and space. Humanity had arrived as a nasty shock. Humanity practically was things that didn't have a position in time and space, such as imagination, pity, hope, history and belief. Take those away and all you had was an ape that fell out of trees a lot.

Intelligent life was, therefore, an anomaly. It made the filing untidy. The Auditors hated things like that. Periodically, they tried to tidy things up a little.

The year before, astronomers across the Discworld had been puzzled to see the stars wheel gently across the sky as the world-turtle executed a roll. The thickness of the world never allowed them to see why, but Great A'Tuin's ancient head had snaked out and down and had snapped right out of the sky the speeding asteroid that would, had it hit, have meant that no one would have needed to buy a diary ever again.

No, the world could take care of obvious threats like that. So now the grey robes preferred more subtle, cowardly skirmishes in their endless desire for a universe where nothing happened that was not completely predictable.

The butter-side-down effect was only a trivial but telling indicator. It showed an increase in activity. Give up, was their eternal message. Go back to being blobs in the ocean. Blobs are easy.

But the great game went on at many levels, Death knew. And often it was hard to know who was playing.

every cause has its effect, he said aloud. so every effect has its cause.

He nodded at the Death of Rats. show me, said Death. show me . . . a beginning.

Tick

It was a bitter winter's night. The man hammered on the back door, sending snow sliding off the roof.

The girl, who had been admiring her new hat in the mirror, tweaked the already low neckline of her dress for slightly more exposure, just in case the caller was male, and went and opened the door.

A figure was outlined against the freezing starlight. Flakes were already building up on his cloak.

'Mrs Ogg? The midwife?' he said.

'It's Miss, actually,' she said proudly. 'And witch, too, o'course.' She indicated her new black pointy hat. She was still at the stage of wearing it in the house.

'You must come at once. It's very urgent.'

The girl looked suddenly panic-stricken. 'Is it Mrs Weaver?

I didn't reckon she was due for another couple of we-'

'I have come a long way,' said the figure. 'They say you are the best in the world.'

'What? Me? I've only delivered one!' said Miss Ogg, now looking hunted. 'Biddy Spective is a lot more experienced than me! And old Minnie Forthwright! Mrs Weaver was going to be my first solo, 'cos she's built like a wardro-'

'I do beg your pardon. I will not trespass further on your time.'

The stranger retreated into the flake-speckled shadows.

'Hello?' said Miss Ogg. 'Hello?'

But there was nothing there, except footprints. Which stopped in the middle of the snow-covered path . . .

Tick

There was a hammering on the door. Mrs Ogg put down the child that had been sitting on her knee and went and raised the latch.

A dark figure stood outlined against the warm summer evening sky, and there was something strange about its shoulders.

'Mrs Ogg? You are married now?'

'Yep. Twice,' said Mrs Ogg cheerfully. 'What can I do for y-'

'You must come at once. It's very urgent.'

'I didn't know anyone was-'

'I have come a long way,' said the figure.

Mrs Ogg paused. There was something in the way he had pronounced long. And now she could see that the whiteness on the cloak was snow, melting fast. Faint memory stirred.

'Well, now,' she said, because she'd learned a lot in the last twenty years or so, 'that's as may be, and I'll always do the best I can, ask anyone. But I wouldn't say I'm the best. Always learnin' something new, that's me.'

'Oh. In that case I will call at a more convenient . . . moment.'

'Why've you got snow on-?'

But, without ever quite vanishing, the stranger was no longer present . . .

Tick

There was a hammering on the door. Nanny Ogg carefully put down her brandy nightcap and stared at the wall for a moment. Now a lifetime of edge witchery* had honed senses that most people never really knew they had, and something in her head went 'click'.

On the hob the kettle for her hot-water bottle was just coming to the boil.

She laid down her pipe, got up and opened the door on this springtime midnight.

'You've come a long way, I'm thinking,' she said, showing no surprise at the dark figure.

'That is true, Mrs Ogg.'

'Everyone who knows me calls me Nanny.'

She looked down at the melting snow dripping off the cloak. It hadn't snowed up here for a month.

'And it's urgent, I expect?' she said, as memory unrolled.

'Indeed.'

'And now you got to say, "You must come at once."'

'You must come at once.'

'Well, now,' she said. 'I'd say, yes, I'm a pretty good midwife, though I do say it myself. I've seen hundreds into the world. Even trolls, which is no errand for the inexperienced. I know birthing backwards and forwards and damn near sideways at times. Always been ready to learn something new, though.' She looked down modestly. 'I wouldn't say I'm the best,' she said, 'but I can't think of anyone better, I have to say.'

'You must leave with me now.'

'Oh, I must, must I?' said Nanny Ogg.

'Yes!'

An edge witch thinks fast, because edges can shift so quickly. And she learns to tell when a mythology is unfolding, and when the best you can do is put yourself in its path and run to keep up.

'I'll just go and get-'

'There is no time.'

'But I can't just walk right out and-'

'Now.'

Nanny reached behind the door for her birthing bag, always kept there for just such occasions as this, full of the things she knew she'd want and a few of the things she always prayed she'd never need.

'Right,' she said.

She left.

Tick

The kettle was just boiling when Nanny walked back into her kitchen. She stared at it for a moment and then moved it off the fire.

There was still a drop of brandy left in the glass by her chair. She drained that, then refilled the glass to the brim from the bottle.

She picked up her pipe. The bowl was still warm. She pulled on it, and the coals crackled.

Then she took something out of her bag, which was now a good deal emptier, and, brandy glass in her hand, sat down to look at it.

'Well,' she said at last. 'That was . . . very unusual . . .'

Tick

Death watched the image fade. A few flakes of snow that had blown out of the mirror had already melted on the floor, but there was still a whiff of pipe smoke in the air.

ah, i see, he said. a birthing, in strange circumstances. but is that what the problem was or was that what the solution will be?

squeak, said the Death of Rats.

quite so, said Death. you may very well be right. I do know that the midwife will never tell me.

The Death of Rats looked surprised. Squeak?

Death smiled. death? asking after the life of a child? no. she would not.

''scuse me,' said the raven, 'but how come Miss Ogg became Mrs Ogg? Sounds like a bit of a rural arrangement, if you catch my meaning.'

witches are matrilineal, said Death. they find it much easier to change men than to change names.

He went back to his desk and opened a drawer.

There was a thick book there, bound in night. On the cover, where a book like this might otherwise say 'Our Wedding' or 'Acme Photo Album', it said 'MEMORIES'.

Death turned the heavy pages carefully. Some of the memories escaped as he did so, forming brief pictures in the air before the page turned, and they went flying and fading into the distant, dark corners of the room. There were snatches of sound, too, of laughter, tears, screams and for some reason a brief burst of xylophone music, which caused him to pause for a moment.

An immortal has a great deal to remember. Sometimes it's better to put things where they will be safe.

One ancient memory, brown and cracking round the edges, lingered in the air over the desk. It showed five figures, four on horseback, one in a chariot, all apparently riding out of a thunderstorm. The horses were at a flat gallop. There was a lot of smoke and flame and general excitement.

ah, the old days, said Death. before there was this fashion for having a solo career.

squeak? the Death of Rats enquired.

oh, yes, said Death. once there were five of us. five horsemen. but you know how things are. there's always a row. creative disagreements, rooms being trashed, that sort of thing. He sighed. and things said that perhaps should not have been said.

He turned a few more pages and sighed again. When you needed an ally, and you were Death, on whom could you absolutely rely?

His thoughtful gaze fell on the teddy bear mug.

Of course, there was always family. Yes. He'd promised not to do this again, but he'd never got the hang of promises.

He got up and went back to the mirror. There was not a lot of time. Things in the mirror were closer than they appeared.

There was a slithering noise, a breathless moment of silence, and a crash like a bag of skittles being dropped.

The Death of Rats winced. The raven took off hurriedly.

help me up, please, said a voice from the shadows. and then please clean up the damn butter.

Tick

He prodded with a sandal the dozing form of Clodpool the apprentice, and said: 'I have seen. Now I understand.'

Then he stopped, and looked at the thing next to Clodpool.

'What is that amazing thing?' he said.

'Er . . . er . . . it's a tree, master,' said Clodpool, still not quite awake. 'Remember? It was there yesterday.'

'There was no yesterday.'

'Er . . . er . . . I think there was, master,' said Clodpool, struggling to his feet. 'Remember? We came up here and I cooked a meal, and had the rind off your sklang because you didn't want it.'

'I remember yesterday,' said Wen thoughtfully. 'But the memory is in my head now. Was yesterday real? Or is it only the memory that is real? Truly, yesterday I was not born.'

Clodpool's face became a mask of agonized incomprehension.

'Dear stupid Clodpool, I have learned everything,' said Wen. 'In the cup of the hand there is no past, no future. There is only now. There is no time but the present. We have a great deal to do.'

Clodpool hesitated. There was something new about his master. There was a glow in his eyes and, when he moved, there were strange silvery-blue lights in the air, like reflections from liquid mirrors.

'She has told me everything,' Wen went on. 'I know that time was made for men, not the other way round. I have learned how to shape it and bend it. I know how to make a moment last for ever, because it already has. And I can teach these skills even to you, Clodpool. I have heard the heartbeat of the universe. I know the answers to many questions. Ask me.'

The apprentice gave him a bleary look. It was too early in the morning for it to be early in the morning. That was the only thing that he currently knew for sure.

'Er . . . what does master want for breakfast?' he said.

Wen looked down from their camp and across the snowfields and purple mountains to the golden daylight creating the world, and mused upon certain aspects of humanity.

'Ah,' he said. 'One of the difficult ones.'

For something to exist, it has to be observed.

For something to exist, it has to have a position in time and space.

And this explains why nine-tenths of the mass of the universe is unaccounted for.

Nine-tenths of the universe is the knowledge of the position and direction of everything in the other tenth. Every atom has its biography, every star its file, every chemical exchange its equivalent of the inspector with a clipboard. It is unaccounted for because it is doing the accounting for the rest of it, and you cannot see the back of your own head.*

Nine-tenths of the universe, in fact, is the paperwork.

And if you want the story, then remember that a story does not unwind. It weaves. Events that start in different places and different times all bear down on that one tiny point in space-time, which is the perfect moment.

Supposing an emperor was persuaded to wear a new suit of clothes whose material was so fine that, to the common eye, the clothes weren't there. And suppose a little boy pointed out this fact in a loud, clear voice . . .

Then you have The Story of the Emperor Who Had No Clothes.

But if you knew a bit more, it would be The Story of the Boy Who Got a Well-Deserved Thrashing from His Dad for Being Rude to Royalty, and Was Locked Up.

Or The Story of the Whole Crowd Who Were Rounded Up by the Guards and Told 'This Didn't Happen, Okay? Does Anyone Want to Argue?'

Or it could be a story of how a whole kingdom suddenly saw the benefits of the 'new clothes', and developed an enthusiasm for healthy sports* in a lively and refreshing atmosphere which got many new adherents every year, and led to a recession caused by the collapse of the conventional clothing industry.

It could even be a story about The Great Pneumonia Epidemic of '09.

It all depends on how much you know.

Supposing you'd watched the slow accretion of snow over thousands of years as it was compressed and pushed over the deep rock until the glacier calved its icebergs into the sea, and you watched an iceberg drift out through the chilly waters, and you got to know its cargo of happy polar bears and seals as they looked forward to a brave new life in the other hemisphere where they say the ice floes are lined with crunchy penguins, and then wham! Tragedy loomed in the shape of thousands of tons of unaccountably floating iron and an exciting soundtrack . . .

. . . you'd want to know the whole story.

And this one starts with desks.

This is the desk of a professional. It is clear that their job is their life. There are . . . human touches, but these are the human touches that strict usage allows in a chilly world of duty and routine.

Mostly they're on the only piece of real colour in this picture of blacks and greys. It's a coffee mug. Someone somewhere wanted to make it a jolly mug. It bears a rather unconvincing picture of a teddy bear, and the legend 'To The World's Greatest Grandad' and the slight change in the style of lettering on the word 'Grandad' makes it clear that this has come from one of those stalls that have hundreds of mugs like this, declaring that they're for the world's greatest Grandad/Dad/Mum/Granny/Uncle/Aunt/Blank. Only someone whose life contains very little else, one feels, would treasure a piece of gimcrackery like this.

It currently holds tea, with a slice of lemon.

The bleak desktop also contains a paperknife in the shape of a scythe and a number of hourglasses.

Death picks up the mug in a skeletal hand . . .

. . . and took a sip, pausing only to look again at the wording he'd read thousands of times before, and then put it down.

very well, he said, in tones of funeral bells. show me.

The last item on the desktop was a mechanical contrivance. 'Contrivance' was exactly the right kind of word for it. Most of it was two discs. One was horizontal and contained a circlet of very small squares of what would prove to be carpet. The other was set vertically and had a large number of arms, each one of which held a very small slice of buttered toast. Each slice was set so that it could spin freely as the turning of the wheel brought it down towards the carpet disc.

I believe I am beginning to get the idea, said Death.

The small figure by the machine saluted smartly and beamed, if a rat skull could beam. It pulled a pair of goggles over its eye sockets, hitched up its robe and clambered into the machine.

Death was never quite sure why he allowed the Death of Rats to have an independent existence. After all, being Death meant being the Death of everything, including rodents of all descriptions. But perhaps everyone needs a tiny part of themselves that can, metaphorically, be allowed to run naked in the rain*, to think the unthinkable thoughts, to hide in corners and spy on the world, to do the forbidden but enjoyable deeds.

Slowly, the Death of Rats pushed the treadles. The wheels began to spin.

'Exciting, eh?' said a hoarse voice by Death's ear. It belonged to Quoth, the raven, who had attached himself to the household as the Death of Rats' personal transport and crony. He was, he always said, only in it for the eyeballs.

The carpets began to turn. The tiny toasties slapped down randomly, sometimes with a buttery squelch, sometimes without. Quoth watched carefully, in case any eyeballs were involved.

Death saw that some time and effort had been spent devising a mechanism to rebutter each returning slice. An even more complex one measured the number of buttered carpets.

After a couple of complete turns the lever of the buttered carpet ratio device had moved to 60 per cent, and the wheels stopped.

well? said Death. if you did it again, it could well be that-

The Death of Rats shifted a gear lever and began to pedal again.

squeak, it commanded. Death obediently leaned closer.

This time the needle went only as high as 40 per cent.

Death leaned closer still.

The eight pieces of carpet that had been buttered this time were, in their entirety, the pieces that had been missed first time round.

Spidery cogwheels whirred in the machine. A sign emerged, rather shakily, on springs, with an effect that was the visual equivalent of the word 'boing'.

A moment later two sparklers spluttered fitfully into life and sizzled away on either side of the word: MALIGNITY.

Death nodded. It was just as he'd suspected.

He crossed his study, the Death of Rats scampering ahead of him, and reached a full-length mirror. It was dark, like the bottom of a well. There was a pattern of skulls and bones around the frame, for the sake of appearances; Death could not look himself in the skull in a mirror with cherubs and roses around it.

The Death of Rats climbed the frame in a scrabble of claws and looked at Death expectantly from the top. Quoth fluttered over and pecked briefly at his own reflection, on the basis that anything was worth a try.

show me, said Death. show me . . . my thoughts.

A chessboard appeared, but it was triangular, and so big that only the nearest point could be seen. Right on this point was the world - turtle, elephants, the little orbiting sun and all. It was the Discworld, which existed only just this side of total improbability and, therefore, in border country. In border country the border gets crossed, and sometimes things creep into the universe that have rather more on their mind than a better life for their children and a wonderful future in the fruit-picking and domestic service industries.

On every other black or white triangle of the chessboard, all the way to infinity, was a small grey shape, rather like an empty hooded robe.

Why now? thought Death.

He recognized them. They were not life forms. They were . . . non-life forms. They were the observers of the operation of the universe, its clerks, its auditors. They saw to it that things spun and rocks fell.

And they believed that for a thing to exist it had to have a position in time and space. Humanity had arrived as a nasty shock. Humanity practically was things that didn't have a position in time and space, such as imagination, pity, hope, history and belief. Take those away and all you had was an ape that fell out of trees a lot.

Intelligent life was, therefore, an anomaly. It made the filing untidy. The Auditors hated things like that. Periodically, they tried to tidy things up a little.

The year before, astronomers across the Discworld had been puzzled to see the stars wheel gently across the sky as the world-turtle executed a roll. The thickness of the world never allowed them to see why, but Great A'Tuin's ancient head had snaked out and down and had snapped right out of the sky the speeding asteroid that would, had it hit, have meant that no one would have needed to buy a diary ever again.

No, the world could take care of obvious threats like that. So now the grey robes preferred more subtle, cowardly skirmishes in their endless desire for a universe where nothing happened that was not completely predictable.

The butter-side-down effect was only a trivial but telling indicator. It showed an increase in activity. Give up, was their eternal message. Go back to being blobs in the ocean. Blobs are easy.

But the great game went on at many levels, Death knew. And often it was hard to know who was playing.

every cause has its effect, he said aloud. so every effect has its cause.

He nodded at the Death of Rats. show me, said Death. show me . . . a beginning.

Tick

It was a bitter winter's night. The man hammered on the back door, sending snow sliding off the roof.

The girl, who had been admiring her new hat in the mirror, tweaked the already low neckline of her dress for slightly more exposure, just in case the caller was male, and went and opened the door.

A figure was outlined against the freezing starlight. Flakes were already building up on his cloak.

'Mrs Ogg? The midwife?' he said.

'It's Miss, actually,' she said proudly. 'And witch, too, o'course.' She indicated her new black pointy hat. She was still at the stage of wearing it in the house.

'You must come at once. It's very urgent.'

The girl looked suddenly panic-stricken. 'Is it Mrs Weaver?

I didn't reckon she was due for another couple of we-'

'I have come a long way,' said the figure. 'They say you are the best in the world.'

'What? Me? I've only delivered one!' said Miss Ogg, now looking hunted. 'Biddy Spective is a lot more experienced than me! And old Minnie Forthwright! Mrs Weaver was going to be my first solo, 'cos she's built like a wardro-'

'I do beg your pardon. I will not trespass further on your time.'

The stranger retreated into the flake-speckled shadows.

'Hello?' said Miss Ogg. 'Hello?'

But there was nothing there, except footprints. Which stopped in the middle of the snow-covered path . . .

Tick

There was a hammering on the door. Mrs Ogg put down the child that had been sitting on her knee and went and raised the latch.

A dark figure stood outlined against the warm summer evening sky, and there was something strange about its shoulders.

'Mrs Ogg? You are married now?'

'Yep. Twice,' said Mrs Ogg cheerfully. 'What can I do for y-'

'You must come at once. It's very urgent.'

'I didn't know anyone was-'

'I have come a long way,' said the figure.

Mrs Ogg paused. There was something in the way he had pronounced long. And now she could see that the whiteness on the cloak was snow, melting fast. Faint memory stirred.

'Well, now,' she said, because she'd learned a lot in the last twenty years or so, 'that's as may be, and I'll always do the best I can, ask anyone. But I wouldn't say I'm the best. Always learnin' something new, that's me.'

'Oh. In that case I will call at a more convenient . . . moment.'

'Why've you got snow on-?'

But, without ever quite vanishing, the stranger was no longer present . . .

Tick

There was a hammering on the door. Nanny Ogg carefully put down her brandy nightcap and stared at the wall for a moment. Now a lifetime of edge witchery* had honed senses that most people never really knew they had, and something in her head went 'click'.

On the hob the kettle for her hot-water bottle was just coming to the boil.

She laid down her pipe, got up and opened the door on this springtime midnight.

'You've come a long way, I'm thinking,' she said, showing no surprise at the dark figure.

'That is true, Mrs Ogg.'

'Everyone who knows me calls me Nanny.'

She looked down at the melting snow dripping off the cloak. It hadn't snowed up here for a month.

'And it's urgent, I expect?' she said, as memory unrolled.

'Indeed.'

'And now you got to say, "You must come at once."'

'You must come at once.'

'Well, now,' she said. 'I'd say, yes, I'm a pretty good midwife, though I do say it myself. I've seen hundreds into the world. Even trolls, which is no errand for the inexperienced. I know birthing backwards and forwards and damn near sideways at times. Always been ready to learn something new, though.' She looked down modestly. 'I wouldn't say I'm the best,' she said, 'but I can't think of anyone better, I have to say.'

'You must leave with me now.'

'Oh, I must, must I?' said Nanny Ogg.

'Yes!'

An edge witch thinks fast, because edges can shift so quickly. And she learns to tell when a mythology is unfolding, and when the best you can do is put yourself in its path and run to keep up.

'I'll just go and get-'

'There is no time.'

'But I can't just walk right out and-'

'Now.'

Nanny reached behind the door for her birthing bag, always kept there for just such occasions as this, full of the things she knew she'd want and a few of the things she always prayed she'd never need.

'Right,' she said.

She left.

Tick

The kettle was just boiling when Nanny walked back into her kitchen. She stared at it for a moment and then moved it off the fire.

There was still a drop of brandy left in the glass by her chair. She drained that, then refilled the glass to the brim from the bottle.

She picked up her pipe. The bowl was still warm. She pulled on it, and the coals crackled.

Then she took something out of her bag, which was now a good deal emptier, and, brandy glass in her hand, sat down to look at it.

'Well,' she said at last. 'That was . . . very unusual . . .'

Tick

Death watched the image fade. A few flakes of snow that had blown out of the mirror had already melted on the floor, but there was still a whiff of pipe smoke in the air.

ah, i see, he said. a birthing, in strange circumstances. but is that what the problem was or was that what the solution will be?

squeak, said the Death of Rats.

quite so, said Death. you may very well be right. I do know that the midwife will never tell me.

The Death of Rats looked surprised. Squeak?

Death smiled. death? asking after the life of a child? no. she would not.

''scuse me,' said the raven, 'but how come Miss Ogg became Mrs Ogg? Sounds like a bit of a rural arrangement, if you catch my meaning.'

witches are matrilineal, said Death. they find it much easier to change men than to change names.

He went back to his desk and opened a drawer.

There was a thick book there, bound in night. On the cover, where a book like this might otherwise say 'Our Wedding' or 'Acme Photo Album', it said 'MEMORIES'.

Death turned the heavy pages carefully. Some of the memories escaped as he did so, forming brief pictures in the air before the page turned, and they went flying and fading into the distant, dark corners of the room. There were snatches of sound, too, of laughter, tears, screams and for some reason a brief burst of xylophone music, which caused him to pause for a moment.

An immortal has a great deal to remember. Sometimes it's better to put things where they will be safe.

One ancient memory, brown and cracking round the edges, lingered in the air over the desk. It showed five figures, four on horseback, one in a chariot, all apparently riding out of a thunderstorm. The horses were at a flat gallop. There was a lot of smoke and flame and general excitement.

ah, the old days, said Death. before there was this fashion for having a solo career.

squeak? the Death of Rats enquired.

oh, yes, said Death. once there were five of us. five horsemen. but you know how things are. there's always a row. creative disagreements, rooms being trashed, that sort of thing. He sighed. and things said that perhaps should not have been said.

He turned a few more pages and sighed again. When you needed an ally, and you were Death, on whom could you absolutely rely?

His thoughtful gaze fell on the teddy bear mug.

Of course, there was always family. Yes. He'd promised not to do this again, but he'd never got the hang of promises.

He got up and went back to the mirror. There was not a lot of time. Things in the mirror were closer than they appeared.

There was a slithering noise, a breathless moment of silence, and a crash like a bag of skittles being dropped.

The Death of Rats winced. The raven took off hurriedly.

help me up, please, said a voice from the shadows. and then please clean up the damn butter.

Tick

Recenzii

“In a better world he would be acclaimed as a great writer rather than a merely successful one…This is the best Pratchett I’ve read…ought to be a strong contender for the Booker prize.” — Charles Spencer, Sunday Telegraph

“Reads with all the polished fluency and sure-footed pacing that have become Pratchett’s hallmarks over the years.” — Peter Ingham, Times on Saturday

“Terry Pratchett is one of the great inventors of secondary — or imaginative or alternative — worlds. He is not derivative. He is too strong…He has the real energy of the primary storyteller.” — A.S. Byatt, The Times

“The unique selling point of the Discworld novels is their irony, allied to lashings of broad pantomime humour.” — TES

“Fans look to him for brilliantly funny dialogue, high peaks of imagination and a sense of participating in events which are strange, yet filled with everyday occurrences — the real world in disguise.” — The Times

"In a better world he would be acclaimed as a great writer rather than a merely successful one...This is the best Pratchett I've read...ought to be a strong contender for the Booker prize." -- Charles Spencer, "Sunday Telegraph""Reads with all the polished fluency and sure-footed pacing that have become Pratchett's hallmarks over the years." -- Peter Ingham, "Times on Saturday""Terry Pratchett is one of the great inventors of secondary -- or imaginative or alternative -- worlds. He is not derivative. He is too strong...He has the real energy of the primary storyteller." -- A.S. Byatt, "The Times""The unique selling point of the Discworld novels is their irony, allied to lashings of broad pantomime humour." -- "TES""Fans look to him for brilliantly funny dialogue, high peaks of imagination and a sense of participating in events which are strange, yet filled with everyday occurrences -- the real world in disguise." -- "The Times"

“Reads with all the polished fluency and sure-footed pacing that have become Pratchett’s hallmarks over the years.” — Peter Ingham, Times on Saturday

“Terry Pratchett is one of the great inventors of secondary — or imaginative or alternative — worlds. He is not derivative. He is too strong…He has the real energy of the primary storyteller.” — A.S. Byatt, The Times

“The unique selling point of the Discworld novels is their irony, allied to lashings of broad pantomime humour.” — TES

“Fans look to him for brilliantly funny dialogue, high peaks of imagination and a sense of participating in events which are strange, yet filled with everyday occurrences — the real world in disguise.” — The Times

"In a better world he would be acclaimed as a great writer rather than a merely successful one...This is the best Pratchett I've read...ought to be a strong contender for the Booker prize." -- Charles Spencer, "Sunday Telegraph""Reads with all the polished fluency and sure-footed pacing that have become Pratchett's hallmarks over the years." -- Peter Ingham, "Times on Saturday""Terry Pratchett is one of the great inventors of secondary -- or imaginative or alternative -- worlds. He is not derivative. He is too strong...He has the real energy of the primary storyteller." -- A.S. Byatt, "The Times""The unique selling point of the Discworld novels is their irony, allied to lashings of broad pantomime humour." -- "TES""Fans look to him for brilliantly funny dialogue, high peaks of imagination and a sense of participating in events which are strange, yet filled with everyday occurrences -- the real world in disguise." -- "The Times"