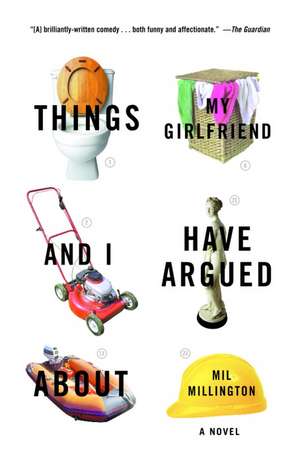

Things My Girlfriend and I Have Argued about

Autor Mil Millingtonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2002

Its fractured thriller plot punctuated by blazingly hilarious set-piece arguments between the hapless Pel and the unflappable Ursula, Things My Girlfriend and I Have Argued About is a brilliant comic novel examining the unique warfare in long-term relationships.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 49.64 lei 3-5 săpt. | +26.27 lei 7-13 zile |

| Orion Publishing Group – 26 ian 2006 | 49.64 lei 3-5 săpt. | +26.27 lei 7-13 zile |

| Villard Books – 31 dec 2002 | 114.38 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 114.38 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.89€ • 22.68$ • 18.27£

21.89€ • 22.68$ • 18.27£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812966664

ISBN-10: 081296666X

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Ediția:Us.

Editura: Villard Books

ISBN-10: 081296666X

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Ediția:Us.

Editura: Villard Books

Extras

A THIN BEAM OF RED LIGHT

Where the hell are the car keys?”

I’m now late. Ten minutes ago I was early. I was wandering about in a too-early limbo, in fact; scratching out a succession of ludicrously trivial and unsatisfying things to do, struggling against the finger-drumming effort of burning away sections of the too-earliness. The children, quick to sense I was briefly doomed to wander the earth without reason or rest, had attached themselves, one to each of my legs. I clumped around the house like a man in magnetic boots while they laughed themselves breathless and shot at each other with wagging fingers and spit-gargling mouth noises from the cover of opposite knees.

Now, however, I’m in a fury of lateness. The responsibility for this rests wholly with the car keys and thereby with their immediate superior—my girlfriend, Ursula.

“Where—where the hell—are the car keys?” I shout down the stairs. Again.

Reason has long since fled. I’ve looked in places where I know there is no possible chance of the car keys lurking. Then I’ve rechecked all those places again. Just in case, you know, I suffered transitory hysterical blindness the first time I looked. Then I’ve looked down, gasping with exhaustion, begged the children to please get off my legs now, and looked a third time. I’m a single degree of enraged frustration away from continuing the search along the only remaining path, which is slashing open the cushion covers, pulling up the floorboards and pickaxing through the plasterboard false wall in the attic.

I do a semi-controlled fall down the stairs to the kitchen, where Ursula is making herself a cup of coffee in a protective bubble of her own, non-late, serene indifference.

“Well?” I’m so clenched I have to shake the word from my head.

“Well what?”

“What do you mean ‘Well what’? I’ve just asked you twice.”

“I didn’t hear you, Pel. I had the radio on.” Ursula nods towards the pocket-sized transistor radio on the shelf. Which is off.

“On what? On stun? Where are the damn car keys?”

“Where they always are.”

“I will kill you.”

“Not, I imagine . . .” Ursula presents a small theater of stirring milk into her coffee. “. . . with exhaust fumes.”

“Arrrrgggh!” Then, again, to emphasize the point, “Arrrrgggh!” That out of my system, I return again to measured debate. “Well, obviously, I didn’t think to look where they always are. Good Lord—how banal would I have to be to go there? However, My Precious, just so we can share a smile at the laughable, prosaic obviousness of it all, WHERE ARE THE CAR KEYS? ALWAYS?”

“They are in the front room. On the shelf. Behind the Lava Lamp.”

“And that’s where they always are, is it? You don’t see any contradiction at all in their always-are place being somewhere they have never been before this morning?”

“It’s where I put them every day.”

I snatch up the keys and hurl myself towards the door, jerking on my jacket as I move; one arm thrust into the air, waggling itself urgently up the sleeve as if it’s attached to a primary school pupil who knows the answer. “That’s a foul and shameless lie.”

As my trailing arm hooks the front door shut behind me, Ursula shouts over the top of her coffee cup, “Bring back some bread—we’re out of bread.” It’s 9:17 a.m.

The story in whose misleadingly calm shallows you’re standing right now is not a tragedy. How do I know? Because a tragedy is the tale of a person who holds the seeds of his own destruction within him. This is entirely contrary to my situation—everyone else holds the seeds of my destruction within them; I just wanted to keep my head down and hope my lottery numbers came up, thanks very much. This story is therefore not a tragedy, for technical rea- sons.

But never mind that now, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let’s just stick a pin in the calendar, shrug “Why not?” and begin on a routine Sunday just after my triumphant car-key offensive. Nothing but the tiniest whiffs of what is to come are about my nostrils. My life is uncluttered with incident and all is tranquil.

Dad, can we go to Laser Wars?”

“It’s six-thirty a.m., Jonathan, Laser Wars isn’t open yet.”

“Dad will take you to Laser Wars after he’s mowed the lawn, Jonathan.”

It appears I’m mowing the lawn today, then.

“Mow the lawn! Mow the lawn!” Peter jumps up and down on the bed, each time landing ever closer to my groin.

“Dad—mow the lawn. Come on, quickly,” instructs Jonathan.

There’s very little chance of my mowing the lawn quickly as we have a sweat-powered mower, rather than an electric- or petrol-driven one. Ursula was insistent—not that she’s ever non-insistent—that we get an ancient, heavy iron affair (clearly built to instill Christian values into the inmates of a Dickensian debtors’ prison) because it is more friendly to the environment than a mower that uses fossil fuels to protect one’s rupturing stomach muscles. Almost without exception, things that are friendly to the environment are the sworn enemies of Pel.

Still, out there grunting my way up and down the grass, my children laughing at the threat of traumatic amputation as they circle around me, girlfriend calling out from the kitchen, “Cup of tea? Can you make me a cup of tea when you’re finished?”—it’s a little picture of domestic heaven, isn’t it? You never realize the value of wearying matter-of-factness until it’s gone.

• • •

Have you finished?” Ursula has watched through the window as I’ve returned from the lawn heaving the mower behind me, placed it by the fence, made to come into the house, caught her eye, gone back to it and wearily removed all the matted grass from the blades and cogs, made to come into the house, caught her eye, returned to sweep all the removed matted grass from the yard and clear it away into the bin, and—staring resolutely ahead—come into the house.

“Yes, I’ve finished.”

“You’re not going to go round the edges with the clippers, then?”

“That’s right. Precisely that meaning of finished.”

“I really can’t understand you. You always do this kind of thing—why do a job badly?”

“Because it’s easier. Duh.”

Ursula is saved the embarrassment of not being able to dispute the solidity of this argument because the phone rings and she darts away to answer it. In a frankly shocking turn of events, the kind of thing that makes you call into question all you thought you knew, the phone call is actually for me. The phone has never rung in this house before and not been for Ursula. She must be gutted.

“It’s Terry,” says Ursula, handing me the receiver with the kind of poor attempt at nonchalance you might display when nodding a casual “hi” to the person who dumped you the previous night. Terry Steven Russell, by the way, is my boss.

“Hi, Terry—it’s Sunday.”

“A detail I didn’t need. Listen, have you got some time to talk today?”

“I suppose so. Apart from going to Laser Wars in an hour or so, I don’t think I’m doing anything all day.” (Across the kitchen I note Ursula raise her eyebrows in an “Oh, that’s what you think, is it?” kind of way.)

“Laser Wars? Great. That’s perfect, in fact. I’ll see you there. ’Bye.”

“Yeah, ’b . . .” But he’s already hung up.

What are you thinking?”

“Nothing.”

“Liar.”

Ursula appears to have an, in my opinion, unhealthy obsession with what I’m thinking. It can’t be normal to ask a person, as often as she asks me, “What are you thinking?” In fact, I know it’s not normal. Because I’m normal, and I virtually never ask her what she’s thinking.

I’m apparently not allowed, ever, to be thinking “nothing.” Odd, really, when you consider the number of times—during an argument over something or other I’ve done—I’ll have “I don’t believe it! What was going through your head? Nothing?” thrown over me. The fact is, I find thinking “nothing” enormously easy. It’s not something I’ve had to work at, either. For me, achieving a sort of Zen state is practically effortless. Perhaps “Zen” is even my natural state. Sit me in a chair and do nothing more than leave me alone and—dink!—there I am: Zenned.

However, this—I think you’ll agree—incandescently impressive reasoning would ching off Ursula into the sightless horizon like a bullet off a tank. “Nothing” is simply not a thing I can possibly be thinking. For a while I did try having something prepared. You know, a standby. A list of things I could fall back on when caught with my synapses down. Thus:

Where the hell are the car keys?”

I’m now late. Ten minutes ago I was early. I was wandering about in a too-early limbo, in fact; scratching out a succession of ludicrously trivial and unsatisfying things to do, struggling against the finger-drumming effort of burning away sections of the too-earliness. The children, quick to sense I was briefly doomed to wander the earth without reason or rest, had attached themselves, one to each of my legs. I clumped around the house like a man in magnetic boots while they laughed themselves breathless and shot at each other with wagging fingers and spit-gargling mouth noises from the cover of opposite knees.

Now, however, I’m in a fury of lateness. The responsibility for this rests wholly with the car keys and thereby with their immediate superior—my girlfriend, Ursula.

“Where—where the hell—are the car keys?” I shout down the stairs. Again.

Reason has long since fled. I’ve looked in places where I know there is no possible chance of the car keys lurking. Then I’ve rechecked all those places again. Just in case, you know, I suffered transitory hysterical blindness the first time I looked. Then I’ve looked down, gasping with exhaustion, begged the children to please get off my legs now, and looked a third time. I’m a single degree of enraged frustration away from continuing the search along the only remaining path, which is slashing open the cushion covers, pulling up the floorboards and pickaxing through the plasterboard false wall in the attic.

I do a semi-controlled fall down the stairs to the kitchen, where Ursula is making herself a cup of coffee in a protective bubble of her own, non-late, serene indifference.

“Well?” I’m so clenched I have to shake the word from my head.

“Well what?”

“What do you mean ‘Well what’? I’ve just asked you twice.”

“I didn’t hear you, Pel. I had the radio on.” Ursula nods towards the pocket-sized transistor radio on the shelf. Which is off.

“On what? On stun? Where are the damn car keys?”

“Where they always are.”

“I will kill you.”

“Not, I imagine . . .” Ursula presents a small theater of stirring milk into her coffee. “. . . with exhaust fumes.”

“Arrrrgggh!” Then, again, to emphasize the point, “Arrrrgggh!” That out of my system, I return again to measured debate. “Well, obviously, I didn’t think to look where they always are. Good Lord—how banal would I have to be to go there? However, My Precious, just so we can share a smile at the laughable, prosaic obviousness of it all, WHERE ARE THE CAR KEYS? ALWAYS?”

“They are in the front room. On the shelf. Behind the Lava Lamp.”

“And that’s where they always are, is it? You don’t see any contradiction at all in their always-are place being somewhere they have never been before this morning?”

“It’s where I put them every day.”

I snatch up the keys and hurl myself towards the door, jerking on my jacket as I move; one arm thrust into the air, waggling itself urgently up the sleeve as if it’s attached to a primary school pupil who knows the answer. “That’s a foul and shameless lie.”

As my trailing arm hooks the front door shut behind me, Ursula shouts over the top of her coffee cup, “Bring back some bread—we’re out of bread.” It’s 9:17 a.m.

The story in whose misleadingly calm shallows you’re standing right now is not a tragedy. How do I know? Because a tragedy is the tale of a person who holds the seeds of his own destruction within him. This is entirely contrary to my situation—everyone else holds the seeds of my destruction within them; I just wanted to keep my head down and hope my lottery numbers came up, thanks very much. This story is therefore not a tragedy, for technical rea- sons.

But never mind that now, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let’s just stick a pin in the calendar, shrug “Why not?” and begin on a routine Sunday just after my triumphant car-key offensive. Nothing but the tiniest whiffs of what is to come are about my nostrils. My life is uncluttered with incident and all is tranquil.

Dad, can we go to Laser Wars?”

“It’s six-thirty a.m., Jonathan, Laser Wars isn’t open yet.”

“Dad will take you to Laser Wars after he’s mowed the lawn, Jonathan.”

It appears I’m mowing the lawn today, then.

“Mow the lawn! Mow the lawn!” Peter jumps up and down on the bed, each time landing ever closer to my groin.

“Dad—mow the lawn. Come on, quickly,” instructs Jonathan.

There’s very little chance of my mowing the lawn quickly as we have a sweat-powered mower, rather than an electric- or petrol-driven one. Ursula was insistent—not that she’s ever non-insistent—that we get an ancient, heavy iron affair (clearly built to instill Christian values into the inmates of a Dickensian debtors’ prison) because it is more friendly to the environment than a mower that uses fossil fuels to protect one’s rupturing stomach muscles. Almost without exception, things that are friendly to the environment are the sworn enemies of Pel.

Still, out there grunting my way up and down the grass, my children laughing at the threat of traumatic amputation as they circle around me, girlfriend calling out from the kitchen, “Cup of tea? Can you make me a cup of tea when you’re finished?”—it’s a little picture of domestic heaven, isn’t it? You never realize the value of wearying matter-of-factness until it’s gone.

• • •

Have you finished?” Ursula has watched through the window as I’ve returned from the lawn heaving the mower behind me, placed it by the fence, made to come into the house, caught her eye, gone back to it and wearily removed all the matted grass from the blades and cogs, made to come into the house, caught her eye, returned to sweep all the removed matted grass from the yard and clear it away into the bin, and—staring resolutely ahead—come into the house.

“Yes, I’ve finished.”

“You’re not going to go round the edges with the clippers, then?”

“That’s right. Precisely that meaning of finished.”

“I really can’t understand you. You always do this kind of thing—why do a job badly?”

“Because it’s easier. Duh.”

Ursula is saved the embarrassment of not being able to dispute the solidity of this argument because the phone rings and she darts away to answer it. In a frankly shocking turn of events, the kind of thing that makes you call into question all you thought you knew, the phone call is actually for me. The phone has never rung in this house before and not been for Ursula. She must be gutted.

“It’s Terry,” says Ursula, handing me the receiver with the kind of poor attempt at nonchalance you might display when nodding a casual “hi” to the person who dumped you the previous night. Terry Steven Russell, by the way, is my boss.

“Hi, Terry—it’s Sunday.”

“A detail I didn’t need. Listen, have you got some time to talk today?”

“I suppose so. Apart from going to Laser Wars in an hour or so, I don’t think I’m doing anything all day.” (Across the kitchen I note Ursula raise her eyebrows in an “Oh, that’s what you think, is it?” kind of way.)

“Laser Wars? Great. That’s perfect, in fact. I’ll see you there. ’Bye.”

“Yeah, ’b . . .” But he’s already hung up.

What are you thinking?”

“Nothing.”

“Liar.”

Ursula appears to have an, in my opinion, unhealthy obsession with what I’m thinking. It can’t be normal to ask a person, as often as she asks me, “What are you thinking?” In fact, I know it’s not normal. Because I’m normal, and I virtually never ask her what she’s thinking.

I’m apparently not allowed, ever, to be thinking “nothing.” Odd, really, when you consider the number of times—during an argument over something or other I’ve done—I’ll have “I don’t believe it! What was going through your head? Nothing?” thrown over me. The fact is, I find thinking “nothing” enormously easy. It’s not something I’ve had to work at, either. For me, achieving a sort of Zen state is practically effortless. Perhaps “Zen” is even my natural state. Sit me in a chair and do nothing more than leave me alone and—dink!—there I am: Zenned.

However, this—I think you’ll agree—incandescently impressive reasoning would ching off Ursula into the sightless horizon like a bullet off a tank. “Nothing” is simply not a thing I can possibly be thinking. For a while I did try having something prepared. You know, a standby. A list of things I could fall back on when caught with my synapses down. Thus:

Recenzii

“[A] brilliantly-written comedy . . . both funny and affectionate.” —The Guardian

“There is little to say about coupledom that is not wittily and often movingly explored here. Sharply-written, brilliantly-observed and absolutely hilarious.” —Daily Mail

“A funny and heart-warming comedy about love, fatherhood and being in the wrong places at all the wrong times.”—Essentials

“There is little to say about coupledom that is not wittily and often movingly explored here. Sharply-written, brilliantly-observed and absolutely hilarious.” —Daily Mail

“A funny and heart-warming comedy about love, fatherhood and being in the wrong places at all the wrong times.”—Essentials

Descriere

This brilliant comic novel examining the warfare in long-term relationships was penned by an author named one of Britain's best first novelists of 2002 by "The Guardian." Millington earned fame a year ago with his Web site--also called "Things My Girlfriend and I Have Argued About"--which gained a cult following on both sides of the Atlantic.

Notă biografică

Mil Millington has written for various magazines, radio, and The Guardian (he also had a weekly column in the Guardian Weekend magazine). His website has achieved cult status, and he is also a cofounder and cowriter of the online magazine The Weekly. He lives in England's West Midlands with his girlfriend and their two children.