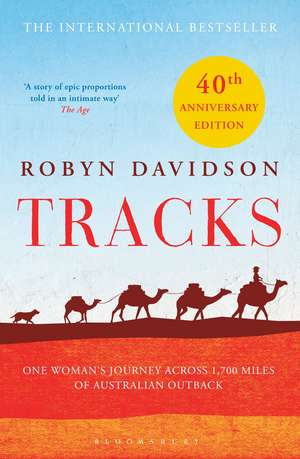

Tracks

Autor Robyn Davidsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – noi 2017

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 48.86 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Bloomsbury Publishing – noi 2017 | 48.86 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Vintage Publishing – 30 apr 1995 | 92.01 lei 3-5 săpt. | +26.35 lei 10-14 zile |

Preț: 48.86 lei

Preț vechi: 63.77 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 73

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.35€ • 9.71$ • 7.80£

9.35€ • 9.71$ • 7.80£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781408896204

ISBN-10: 1408896206

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: 8pp colour

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Anniversary

Editura: Bloomsbury Publishing

Colecția Bloomsbury Paperbacks

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 1408896206

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: 8pp colour

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Anniversary

Editura: Bloomsbury Publishing

Colecția Bloomsbury Paperbacks

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

Caracteristici

This revised edition contains a postscript and a new introduction by the author and an 8pp colour plate section of Rick Smolan's stunning photographs from Robyn's journey

Notă biografică

Robyn Davidson was born on a cattle property in Queensland. She went to Sydney in the late sixties, then returned to study in Brisbane before going to Alice Springs where the events of this book began. Since then she has travelled extensively and has lived in London, New York and India. In the early 1990s she migrated with and wrote about nomads in north west India. She is now based in Melbourne, but spends several months a year in the Indian Himalayas.

Recenzii

A strong, salty fresh book by an original and individual young woman ... This will rank among the best of the books of exploration and travel and, like them, is a record of self-discovery and self-proving

Beautiful, thrilling and ferociously brave, Robyn Davidson's timeless story of her astonishing journey gripped me from the first page to the last. Tracks is an unforgettably powerful book

It gets to the heart of landscape and solitude and becomes a venture to the interior of more than one dimension as its author approaches the hinterland of her own thorny psyche

An absorbing record of human endeavour and courage, a vivid picture of an extraordinary country by a perceptive and sensitive observer, and the story of an inner journey, of "shedding burdens"

As eccentric, undisciplined, flashily brilliant and pig-headed as its author ... Ms Davidson is a born writer, her book deeply moving

Vivid and vivacious ... Davidson is as natural a writer as she is an adventurer

Beautiful, thrilling and ferociously brave, Robyn Davidson's timeless story of her astonishing journey gripped me from the first page to the last. Tracks is an unforgettably powerful book

It gets to the heart of landscape and solitude and becomes a venture to the interior of more than one dimension as its author approaches the hinterland of her own thorny psyche

An absorbing record of human endeavour and courage, a vivid picture of an extraordinary country by a perceptive and sensitive observer, and the story of an inner journey, of "shedding burdens"

As eccentric, undisciplined, flashily brilliant and pig-headed as its author ... Ms Davidson is a born writer, her book deeply moving

Vivid and vivacious ... Davidson is as natural a writer as she is an adventurer

Descriere

A revised, reissued edition of this prize-winning, bestselling account of one woman's solo journey across 1,700 miles of Australian Outback

Extras

1

I arrived in the Alice at five a.m. with a dog, six dollars and a small suitcase full of inappropriate clothes. 'Bring a cardigan for the evenings,' the brochure said. A freezing wind whipped grit down the platform and I stood shivering, holding warm dog flesh, and wondering what foolishness had brought me to this eerie, empty train-station in the centre of nowhere. I turned against the wind, and saw the line of mountains at the edge of town.

There are some moments in life that are like pivots around which your existence turns-small intuitive flashes, when you know you have done something correct for a change, when you think you are on the right track. I watched a pale dawn streak the cliffs with Day-glo and realized this was one of them. It was a moment of pure, uncomplicated confidence-and lasted about ten seconds.

Diggity wriggled out of my arms and looked at me, head cocked, piglet ears flying. I experienced that sinking feeling you get when you know you have conned yourself into doing something difficult and there's no going back. It's all very well, to set off on a train with no money telling yourself that you're really quite a brave and adventurous person, and you'll deal capably with things as they happen, but when you actually arrive at the other end with no one to meet and nowhere to go and nothing to sustain you but a lunatic idea that even you have no real faith in, it suddenly appears much more attractive to be at home on the kindly Queensland coast, discussing plans and sipping gins on the verandah with friends, and making unending lists of lists which get thrown away, and reading books about camels.

The lunatic idea was, basically, to get myself the requisite number of wild camels from the bush and train them to carry my gear, then walk into and about the central desert area. I knew that there were feral camels aplenty in this country. They had been imported in the 1850s along with their Afghani and North Indian owners, to open up the inaccessible areas, to transport food, and to help build the telegraph system and railways that would eventually cause their economic demise. When this happened, those Afghans had let their camels go, heartbroken, and tried to find other work. They were specialists and it wasn't easy. They didn't have much luck with government support either. Their camels, however, had found easy street-it was perfect country for them and they grew and prospered, so that now there are approximately ten thousand roaming the free country and making a nuisance of themselves on cattle properties, getting shot at, and, according to some ecologists, endangering some plant species for which they have a particular fancy. Their only natural enemy is man, they are virtually free of disease, and Australian camels are now rated as some of the best in the world.

The train had been half empty, the journey long. Five hundred miles and two days from Adelaide to Alice Springs. The modern arterial roads around Port Augusta had almost immediately petered out into crinkled, wretched, endless pink tracks leading to the shimmering horizon, and then there was nothing but the dry red parchment of the dead heart, god's majestic hidy-hole, where men are men and women are an afterthought. Snippets of railway car conversation still buzzed around in my head.

'G'day, mind if I sit 'ere?'

(Sighing and looking pointedly out the window or at book.) 'No.'

(Dropping of the eyes to chest level.) 'Where's yer old man?'

'I don't have an old man.'

(Faint gleam in bleary, blood-shot eye, still fixed at chest level.) 'Jesus Christ, mate, you're not goin' to the Alice alone are ya? Listen 'ere, lady, you're fuckin' done for. Them coons'll rape youze for sure. Fuckin' niggers run wild up there ya know. You'll need someone to keep an eye on ya. Tell youze what, I'll shout youze a beer, then we'll go back to your cabin and get acquainted eh? Whaddya reckon?'

I waited until the station had thinned its few bustling arrivals, standing in the vacuum of early morning silence, fighting back my unease, then set off with Diggity towards town.

My first impression as we strolled down the deserted street was of the architectural ugliness of the place, a discomforting contrast to the magnificence of the country which surrounded it. Dust covered everything from the large, dominant corner pub to the tacky, unimaginative shop fronts that lined the main street. Hordes of dead insects clustered in the arcing street lights, and four-wheel-drive vehicles spattered in red dirt, with only two spots swept clean by the windscreen wipers, rattled intermittently through the cement and bitumen town. This grey, cream and hospital-green shopping area gradually gave way to sprawling suburbia until it was stopped short by the great perpendicular red face of the Macdonnell Ranges which borders the southern side of town, and runs unbroken, but for a few spectacular gorges, east and west for several hundred miles. The Todd River, a dry white sandy bed lined with tall columns of silver eucalypts, winds through the town, then cuts into a narrow gap in the mountains. The range, looming menacingly like some petrified prehistoric monster, has, I was to discover, a profound psychological effect on the puny folk below. It sends them troppo. It reminds them of incomprehensible dimensions of time which they almost successfully block out with brick veneer houses and wilted English-style gardens.

I had planned to camp in the creek with the Aborigines until I could find a job and a place to stay, but the harbingers of doom on the train had told me it was suicide to do such a thing. Everyone, from the chronic drunks to the stony men and women with brown wrinkled faces and burnt-out expressions, to the waiters in tuxedos who served and consumed enormous amounts of alcohol, all of them warned me against it. The blacks were unequivocally the enemy. Dirty, lazy, dangerous animals. Stories of young white lasses who innocently strayed down the Todd at night, there to meet their fate worse than death, were told with suspect fervour. It was the only subject anyone had got fired up about. I had heard other stories back home too-of how a young black man was found in an Alice gutter one morning, painted white. Even back in the city where the man in the street was unlikely ever to have seen an Aborigine, let alone spoken to one, that same man could talk at length, with an extraordinary contempt, about what they were like, how lazy and unintelligent they were. This was because of the press, where clich?d images of dirty, stone-age drunks on the dole were about the only coverage Aborigines got, and because everyone had been taught at school that they were not much better than specialized apes, with no culture, no government and no right to existence in a vastly superior white world; aimless wanderers who were backward, primitive and stupid.

It is difficult to sort out fact from fiction, fear from paranoia and goodies from baddies when you are new in a town but something was definitely queer about this one. The place seemed soulless, rootless, but perhaps it was just that which encouraged, in certain circumstances, the extraordinary. Had everyone been trying to put the fear of god into me just because I was an urbanite in the bush? Had I suddenly landed in Ku Klux Klan country? I had spent time before with Aboriginal people-in fact, had had one of the best holidays of my entire life with them. Certainly there had been some heavy drinking and the occasional fight, but that was part of the white Australian tradition too, and could be found in most pubs or parties in the country. If the blacks here were like the blacks there, how could a group of whites be so consumed with fear and hatred? And if they were different here, what had happened to make them that way? Tread carefully, my instincts said. I could sense already a camouflaged violence in this town, and I had to find a safe place to stay. Rabbits, too, have their survival mechanisms.

They say paranoia attracts paranoia: certainly no one else I met ever had such a negative view of Alice Springs. But then I was to get to know it from the gutters up, which may have given me a distorted perspective. It is said that anyone who sees the Todd River flow three times falls in love with the Alice. By the end of the second year, after seeing it freakishly flood more often than that, I had a passionate hatred yet an inexplicable and consuming addiction for it.

There are fourteen thousand people living there of whom one thousand are Aboriginal. The whites consist mainly of government workers, miscellaneous misfits and adventurers, retired cattle or sheep station owners, itinerant station workers, truck drivers and small business operators whose primary function in life is to rip off the tourists, who come by the bus-load from America, Japan and urban Australia, expecting high adventure in this last romantic outpost, and to see the extraordinary desert which surrounds it. There are three major pubs, a few motels, a couple of zed-grade restaurants, and various shops that sell 'I've climbed Ayers Rock' T-shirts, boomerangs made in Taiwan, books on Australiana, and tea towels with noble savages holding spears silhouetted against setting suns. It is a frontier town, characterized by an aggressive masculine ethic and severe racial tensions.

I ate breakfast at a cheap cafe, then stepped out into the glaring street where things were beginning to move, and squinted at my new home. I asked someone where the cheapest accommodation was and they directed me to a caravan park three miles north of town.

It was a hot and dusty walk but interesting. The road followed a tributary of the Todd. Still, straight columns of blue smoke chimneying up through the gum leaves marked Aboriginal camps. On the left were the garages and workshops of industrial Alice-galvanized iron sheds behind which spread the trim lawns and trees of suburbia. When I arrived, the proprietor informed me that it was only three dollars if I had my own tent, otherwise it was eight.

My smile faded. I eyed the cold drinks longingly and went outside for some tepid tap water. I didn't ask if that were free, just in case. Over in the corner of the park some young folk with long hair and patched jeans were pitching a large tent. They looked approachable, so I asked if I could stay with them. They were pleased to offer me shelter and friendliness.

That night, they took me out on the town in their beatup panel-van equipped with all the trappings one associates with free-wheeling urban youth-a five million decibel car stereo and even surf-boards . . . they were heading north. We drove into the dusty lights of the town and stopped by the pub to pick up some booze. The girl, who was shy and very young, suddenly turned to me.

'Oo, look at them, aren't they disgusting. God, they're like apes.'

'Who?'

'The boongs.'

Her boyfriend was leaning up against the bottle-shop, waiting.

'Hurry up, Bill, and let's get out of here. Ugly brutes.' She folded her arms as if she were cold and shivered with repulsion.

I put my head on my arms, bit my tongue, and knew the night was going to be a long one.

The next day I got a job at the pub, starting in two days. Yes, I could stay in a back room of the pub, the payment for which would be deducted from my first week's wages. Meals were provided. Perfect. That gave me time to suss out camel business. I sat in the bar for a while and chatted with the regulars. I discovered there were three camel-men in town-two involved with tourist businesses, and the other an old Afghan who was bringing in camels from the wild to sell to Arabia as meat herds. I met a young geologist who offered to drive me out to meet this man.

The minute I saw Sallay Mahomet it was apparent to me that he knew exactly what he was doing. He exuded the bandy-legged, rope-handling confidence of a man long accustomed to dealing with animals. He was fixing some odd-looking saddles near a dusty yard filled with these strange beasts.

'Yes, what can I do for you?'

'Good morning, Mr Mahomet,' I said confidently. 'My name's Robyn Davidson and um, I've been planning this trip you see, into the central desert and I wanted to get three wild camels and train them for it, and I was wondering if you might be able to help me.'

'Hrrrmppph.'

Sallay glared at me from under bushy white eyebrows. There was a dry grumpiness about him that put me instantly in my place and made me feel like a complete idiot.

'And I suppose you think you'll make it too?'

I looked at the ground, shuffled my feet and mumbled something defensive.

'What do you know about camels then?'

'Ah well, nothing really, I mean these are the first ones I've seen as a matter of fact, but ah . . .'

'Hrrmmph. And what do you know about deserts?'

It was painfully obvious from my silence that I knew very little about anything.

Sallay said he was sorry, he didn't think he could help me, and turned about his business. My cockiness faded. This was going to be harder than I thought, but then it was only the first day.

Next we drove to the tourist place south of town. I met the owner and his wife, a friendly woman who offered me cakes and tea. They looked at one another in silence when I told them of my plan. 'Well, come out here any time you like,' said the man jovially, 'and get to know the animals a bit.' He could barely control the smirk on the other side of his face. My intuition in any case told me to stay away. I didn't like him and I was sure the feeling was mutual. Besides, when I saw how his animals roared and fought, I figured he was probably not the right person to learn from.

The last of the three, the Posel place, was three miles north, and was owned, according to some of the people in the bar, by a maniac.

My geologist friend dropped me off at the pub, and from there I walked north up the Charles River bed. It was a delightful walk, under cool and shady trees. The silence was often broken by packs of camp dogs who raced out with their hackles up to tell me and Diggity to get out of their territory, only to have bottles, cans and curses flung at them by their Aboriginal owners, who none the less smiled and nodded at us.

I arrived in the Alice at five a.m. with a dog, six dollars and a small suitcase full of inappropriate clothes. 'Bring a cardigan for the evenings,' the brochure said. A freezing wind whipped grit down the platform and I stood shivering, holding warm dog flesh, and wondering what foolishness had brought me to this eerie, empty train-station in the centre of nowhere. I turned against the wind, and saw the line of mountains at the edge of town.

There are some moments in life that are like pivots around which your existence turns-small intuitive flashes, when you know you have done something correct for a change, when you think you are on the right track. I watched a pale dawn streak the cliffs with Day-glo and realized this was one of them. It was a moment of pure, uncomplicated confidence-and lasted about ten seconds.

Diggity wriggled out of my arms and looked at me, head cocked, piglet ears flying. I experienced that sinking feeling you get when you know you have conned yourself into doing something difficult and there's no going back. It's all very well, to set off on a train with no money telling yourself that you're really quite a brave and adventurous person, and you'll deal capably with things as they happen, but when you actually arrive at the other end with no one to meet and nowhere to go and nothing to sustain you but a lunatic idea that even you have no real faith in, it suddenly appears much more attractive to be at home on the kindly Queensland coast, discussing plans and sipping gins on the verandah with friends, and making unending lists of lists which get thrown away, and reading books about camels.

The lunatic idea was, basically, to get myself the requisite number of wild camels from the bush and train them to carry my gear, then walk into and about the central desert area. I knew that there were feral camels aplenty in this country. They had been imported in the 1850s along with their Afghani and North Indian owners, to open up the inaccessible areas, to transport food, and to help build the telegraph system and railways that would eventually cause their economic demise. When this happened, those Afghans had let their camels go, heartbroken, and tried to find other work. They were specialists and it wasn't easy. They didn't have much luck with government support either. Their camels, however, had found easy street-it was perfect country for them and they grew and prospered, so that now there are approximately ten thousand roaming the free country and making a nuisance of themselves on cattle properties, getting shot at, and, according to some ecologists, endangering some plant species for which they have a particular fancy. Their only natural enemy is man, they are virtually free of disease, and Australian camels are now rated as some of the best in the world.

The train had been half empty, the journey long. Five hundred miles and two days from Adelaide to Alice Springs. The modern arterial roads around Port Augusta had almost immediately petered out into crinkled, wretched, endless pink tracks leading to the shimmering horizon, and then there was nothing but the dry red parchment of the dead heart, god's majestic hidy-hole, where men are men and women are an afterthought. Snippets of railway car conversation still buzzed around in my head.

'G'day, mind if I sit 'ere?'

(Sighing and looking pointedly out the window or at book.) 'No.'

(Dropping of the eyes to chest level.) 'Where's yer old man?'

'I don't have an old man.'

(Faint gleam in bleary, blood-shot eye, still fixed at chest level.) 'Jesus Christ, mate, you're not goin' to the Alice alone are ya? Listen 'ere, lady, you're fuckin' done for. Them coons'll rape youze for sure. Fuckin' niggers run wild up there ya know. You'll need someone to keep an eye on ya. Tell youze what, I'll shout youze a beer, then we'll go back to your cabin and get acquainted eh? Whaddya reckon?'

I waited until the station had thinned its few bustling arrivals, standing in the vacuum of early morning silence, fighting back my unease, then set off with Diggity towards town.

My first impression as we strolled down the deserted street was of the architectural ugliness of the place, a discomforting contrast to the magnificence of the country which surrounded it. Dust covered everything from the large, dominant corner pub to the tacky, unimaginative shop fronts that lined the main street. Hordes of dead insects clustered in the arcing street lights, and four-wheel-drive vehicles spattered in red dirt, with only two spots swept clean by the windscreen wipers, rattled intermittently through the cement and bitumen town. This grey, cream and hospital-green shopping area gradually gave way to sprawling suburbia until it was stopped short by the great perpendicular red face of the Macdonnell Ranges which borders the southern side of town, and runs unbroken, but for a few spectacular gorges, east and west for several hundred miles. The Todd River, a dry white sandy bed lined with tall columns of silver eucalypts, winds through the town, then cuts into a narrow gap in the mountains. The range, looming menacingly like some petrified prehistoric monster, has, I was to discover, a profound psychological effect on the puny folk below. It sends them troppo. It reminds them of incomprehensible dimensions of time which they almost successfully block out with brick veneer houses and wilted English-style gardens.

I had planned to camp in the creek with the Aborigines until I could find a job and a place to stay, but the harbingers of doom on the train had told me it was suicide to do such a thing. Everyone, from the chronic drunks to the stony men and women with brown wrinkled faces and burnt-out expressions, to the waiters in tuxedos who served and consumed enormous amounts of alcohol, all of them warned me against it. The blacks were unequivocally the enemy. Dirty, lazy, dangerous animals. Stories of young white lasses who innocently strayed down the Todd at night, there to meet their fate worse than death, were told with suspect fervour. It was the only subject anyone had got fired up about. I had heard other stories back home too-of how a young black man was found in an Alice gutter one morning, painted white. Even back in the city where the man in the street was unlikely ever to have seen an Aborigine, let alone spoken to one, that same man could talk at length, with an extraordinary contempt, about what they were like, how lazy and unintelligent they were. This was because of the press, where clich?d images of dirty, stone-age drunks on the dole were about the only coverage Aborigines got, and because everyone had been taught at school that they were not much better than specialized apes, with no culture, no government and no right to existence in a vastly superior white world; aimless wanderers who were backward, primitive and stupid.

It is difficult to sort out fact from fiction, fear from paranoia and goodies from baddies when you are new in a town but something was definitely queer about this one. The place seemed soulless, rootless, but perhaps it was just that which encouraged, in certain circumstances, the extraordinary. Had everyone been trying to put the fear of god into me just because I was an urbanite in the bush? Had I suddenly landed in Ku Klux Klan country? I had spent time before with Aboriginal people-in fact, had had one of the best holidays of my entire life with them. Certainly there had been some heavy drinking and the occasional fight, but that was part of the white Australian tradition too, and could be found in most pubs or parties in the country. If the blacks here were like the blacks there, how could a group of whites be so consumed with fear and hatred? And if they were different here, what had happened to make them that way? Tread carefully, my instincts said. I could sense already a camouflaged violence in this town, and I had to find a safe place to stay. Rabbits, too, have their survival mechanisms.

They say paranoia attracts paranoia: certainly no one else I met ever had such a negative view of Alice Springs. But then I was to get to know it from the gutters up, which may have given me a distorted perspective. It is said that anyone who sees the Todd River flow three times falls in love with the Alice. By the end of the second year, after seeing it freakishly flood more often than that, I had a passionate hatred yet an inexplicable and consuming addiction for it.

There are fourteen thousand people living there of whom one thousand are Aboriginal. The whites consist mainly of government workers, miscellaneous misfits and adventurers, retired cattle or sheep station owners, itinerant station workers, truck drivers and small business operators whose primary function in life is to rip off the tourists, who come by the bus-load from America, Japan and urban Australia, expecting high adventure in this last romantic outpost, and to see the extraordinary desert which surrounds it. There are three major pubs, a few motels, a couple of zed-grade restaurants, and various shops that sell 'I've climbed Ayers Rock' T-shirts, boomerangs made in Taiwan, books on Australiana, and tea towels with noble savages holding spears silhouetted against setting suns. It is a frontier town, characterized by an aggressive masculine ethic and severe racial tensions.

I ate breakfast at a cheap cafe, then stepped out into the glaring street where things were beginning to move, and squinted at my new home. I asked someone where the cheapest accommodation was and they directed me to a caravan park three miles north of town.

It was a hot and dusty walk but interesting. The road followed a tributary of the Todd. Still, straight columns of blue smoke chimneying up through the gum leaves marked Aboriginal camps. On the left were the garages and workshops of industrial Alice-galvanized iron sheds behind which spread the trim lawns and trees of suburbia. When I arrived, the proprietor informed me that it was only three dollars if I had my own tent, otherwise it was eight.

My smile faded. I eyed the cold drinks longingly and went outside for some tepid tap water. I didn't ask if that were free, just in case. Over in the corner of the park some young folk with long hair and patched jeans were pitching a large tent. They looked approachable, so I asked if I could stay with them. They were pleased to offer me shelter and friendliness.

That night, they took me out on the town in their beatup panel-van equipped with all the trappings one associates with free-wheeling urban youth-a five million decibel car stereo and even surf-boards . . . they were heading north. We drove into the dusty lights of the town and stopped by the pub to pick up some booze. The girl, who was shy and very young, suddenly turned to me.

'Oo, look at them, aren't they disgusting. God, they're like apes.'

'Who?'

'The boongs.'

Her boyfriend was leaning up against the bottle-shop, waiting.

'Hurry up, Bill, and let's get out of here. Ugly brutes.' She folded her arms as if she were cold and shivered with repulsion.

I put my head on my arms, bit my tongue, and knew the night was going to be a long one.

The next day I got a job at the pub, starting in two days. Yes, I could stay in a back room of the pub, the payment for which would be deducted from my first week's wages. Meals were provided. Perfect. That gave me time to suss out camel business. I sat in the bar for a while and chatted with the regulars. I discovered there were three camel-men in town-two involved with tourist businesses, and the other an old Afghan who was bringing in camels from the wild to sell to Arabia as meat herds. I met a young geologist who offered to drive me out to meet this man.

The minute I saw Sallay Mahomet it was apparent to me that he knew exactly what he was doing. He exuded the bandy-legged, rope-handling confidence of a man long accustomed to dealing with animals. He was fixing some odd-looking saddles near a dusty yard filled with these strange beasts.

'Yes, what can I do for you?'

'Good morning, Mr Mahomet,' I said confidently. 'My name's Robyn Davidson and um, I've been planning this trip you see, into the central desert and I wanted to get three wild camels and train them for it, and I was wondering if you might be able to help me.'

'Hrrrmppph.'

Sallay glared at me from under bushy white eyebrows. There was a dry grumpiness about him that put me instantly in my place and made me feel like a complete idiot.

'And I suppose you think you'll make it too?'

I looked at the ground, shuffled my feet and mumbled something defensive.

'What do you know about camels then?'

'Ah well, nothing really, I mean these are the first ones I've seen as a matter of fact, but ah . . .'

'Hrrmmph. And what do you know about deserts?'

It was painfully obvious from my silence that I knew very little about anything.

Sallay said he was sorry, he didn't think he could help me, and turned about his business. My cockiness faded. This was going to be harder than I thought, but then it was only the first day.

Next we drove to the tourist place south of town. I met the owner and his wife, a friendly woman who offered me cakes and tea. They looked at one another in silence when I told them of my plan. 'Well, come out here any time you like,' said the man jovially, 'and get to know the animals a bit.' He could barely control the smirk on the other side of his face. My intuition in any case told me to stay away. I didn't like him and I was sure the feeling was mutual. Besides, when I saw how his animals roared and fought, I figured he was probably not the right person to learn from.

The last of the three, the Posel place, was three miles north, and was owned, according to some of the people in the bar, by a maniac.

My geologist friend dropped me off at the pub, and from there I walked north up the Charles River bed. It was a delightful walk, under cool and shady trees. The silence was often broken by packs of camp dogs who raced out with their hackles up to tell me and Diggity to get out of their territory, only to have bottles, cans and curses flung at them by their Aboriginal owners, who none the less smiled and nodded at us.

![[sic]: A Memoir](https://i1.books-express.ro/bt/9781408822463/sic.jpg)