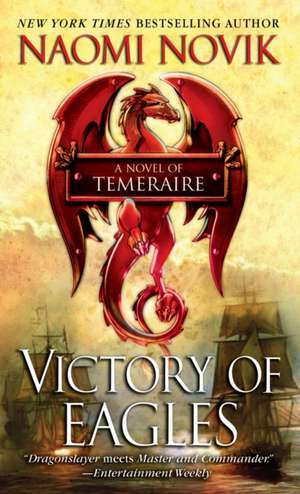

Victory of Eagles: Temeraire

Autor Naomi Noviken Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2009

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (3) | 57.97 lei 17-23 zile | +5.03 lei 7-13 zile |

| Del Rey Books – 30 apr 2009 | 57.97 lei 17-23 zile | +5.03 lei 7-13 zile |

| HarperCollins Publishers – 5 feb 2009 | 69.98 lei 3-5 săpt. | +10.42 lei 7-13 zile |

| Random House LLC US – 12 iul 2022 | 99.35 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 57.97 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 87

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.09€ • 11.54$ • 9.28£

11.09€ • 11.54$ • 9.28£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 18-24 februarie

Livrare express 08-14 februarie pentru 15.02 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345512253

ISBN-10: 0345512251

Pagini: 376

Dimensiuni: 104 x 170 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Colecția Del Rey Books

Seria Temeraire

ISBN-10: 0345512251

Pagini: 376

Dimensiuni: 104 x 170 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Colecția Del Rey Books

Seria Temeraire

Notă biografică

Naomi Novik is the acclaimed author of His Majesty’s Dragon, Throne of Jade, Black Powder War, and Empire of Ivory, the first four volumes of the Temeraire series, recently optioned by Peter Jackson, the Academy Award—winning director of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. A history buff with a particular interest in the Napoleonic era, Novik studied English literature at Brown University, then did graduate work in computer science at Columbia University before leaving to participate in the design and development of the computer game Neverwinter Nights: Shadows of Undrentide. Novik lives in New York City with her husband and six computers.

Extras

Chapter 1

The breeding grounds were called Pen Y Fan, after the hard, jagged slash of the mountain at their heart, like an ax-blade, rimed with ice along its edge and rising barren over the moorlands: a cold, wet Welsh autumn already, coming on towards winter, and the other dragons sleepy and remote, uninterested in anything but their meals. There were a few hundred of them scattered throughout the grounds, mostly established in caves or on rocky ledges, wherever they could fit themselves; nothing of comfort or even order provided for them, except the feedings, and the mowed-bare strip of dirt around the borders, where torches were lit at night to mark the lines past which they might not go, with the town-lights glimmering in the distance, cheerful and forbidden.

Temeraire had hunted out and cleared a large cavern, on his arrival, to sleep in; but it would be damp, no matter what he did in the way of lining it with grass, or flapping his wings to move the air, which in any case did not suit his instinctive notions of dignity: much better to endure every unpleasantness with stoic patience, although that was not very satisfying when no-one would appreciate the effort. The other dragons certainly did not.

He was quite sure he and Laurence had done as they ought, in taking the cure to France, and no-one sensible could disagree; but just in case, Temeraire had steeled himself to meet with either disapproval or contempt, and he had worked out several very fine arguments in his defense. Most importantly, of course, it was just a cowardly, sneaking way of fighting: if the Government wished to beat Napoleon, they ought to fight him directly, and not make his dragons sick to try and make him easy to defeat; as if British dragons could not beat French dragons, without cheating. “And not only that,” he added, “but it would not be only the French dragons who died: our friends from Prussia who are imprisoned in their breeding grounds would also have got sick, and perhaps it might even have gone so far as China; and that would be like stealing someone else’s food, even when you are not hungry; or breaking their eggs.”

He made this impressive speech to the wall of his cave, as practice: they had refused to give him his sand-table, and he had no-one of his crew to jot it down for him, either; he did not have Laurence, who would have helped him work out just what to say. So he repeated the arguments over to himself quietly, instead, so he should not forget them. And if these should not suffice to persuade, he thought, he might point out that after all, he had brought the cure back, in the first place: he and Laurence, with Maximus and Lily and the rest of their formation, and if anyone had a right to say where it should be shared out, they did: no-one would even have known of it if Temeraire had not contrived to be sick in Africa, where the mushrooms which cured it grew.

He might have saved the trouble. No-one accused him of anything, nor, as he had privately, a little wistfully, thought just barely possible, hailed him as a hero; because they did not care.

The older dragons, not feral but retired, were a little curious about the latest developments in the war, but only distantly, more inclined to tell over their own battles of earlier wars; and the rest had plenty of indignation over the recent epidemic, but only in a provincial way. They cared that they and their own fellows had sickened and died; they cared that the cure had taken so long to reach them; but it did not mean anything to them that dragons in France had also been ill, or that the disease would have spread, killing thousands, if Temeraire and Laurence had not taken over the cure; they also did not care that the Lords of the Admiralty had called it treason, and sentenced Laurence to die.

They had nothing to care for. They were fed, and there was enough for everyone. If the shelter was not pleasant, it was no worse than what even the retired dragons were used to, from the days of their active service; they had none of them even heard of a pavilion, or thought they might be made more comfortable than they were. No-one ever molested an egg; the grounds-keepers would take them away, but with infinite care, in waggons lined with straw, hot-water bottles and woolen blankets in the wintertime; and they would bring back reports until the eggs were hatched and no more of anyone’s concern; so everyone knew the eggs were safe in their hands; safer, even, than keeping them oneself, so even the dragons who had not cared to take a captain themselves, at all, would often as not hand over their own eggs. They could not go flying very far, because they were fed at no set time but randomly, from day to day, so if one went away out of ear-shot of the bells, one was likely to come too late, and go hungry all the day. So there was no larger society, no intercourse with the other breeding grounds or with the coverts, except when some other dragon came from afar, to mate; even that was arranged for them. Instead they sat, willing prisoners in their own territory, Temeraire thought bitterly; he would never have endured it if not for Laurence, only for Laurence, who would surely be put to death at once if Temeraire did not obey.

He held himself aloof from their society at first. There was his cave to be arranged: despite its fine prospect it had been left vacant for being inconveniently shallow, and he was rather crammed-in; but there was a much larger chamber beyond, visible through holes in the back wall, which he gradually opened up with the slow and cautious use of his roar. Slower, even, than perhaps necessary—he was very willing to have the task consume several days. The cave had then to be cleared of debris, old gnawed bones and inconvenient boulders, which he scraped out painstakingly even from the corners too small for him to lie in, for neatness’ sake; and he found a few rough boulders in the valley and used them to grind the cave walls a little smoother, by dragging them back and forth, throwing up a great cloud of dust.

It made him sneeze, but he kept on; he was not going to live in a raw untidy hole. He knocked down stalactites from the ceiling, and beat protrusions flat into the floor, and when he was satisfied, he arranged along the sides of what was now his antechamber, with careful nudges of his talons, some attractive rocks and old, dead tree-branches, twisted and bleached white, which he had collected from the woods and ravines. He would have liked a pond and a fountain, but he could not see how to bring the water up, or how to make it run when he had got it there, so he settled for picking out a promontory on Llyn y Fan Fawr which jutted into the lake, and considering it also his own.

To finish he carved the characters of his name into the cliff face by the entrance, and also in English, although the letter R gave him some difficulty and came out looking rather like the reversed numeral 4; then he was done with that, and routine crept up and devoured his days. To rise, when the sun came in at the cave-mouth; to take a little exercise, to nap, to rise again when the herdsmen rang the bell, to eat, then to nap and to exercise again, and then back to sleep; and that was the end of the day, there was nothing more. He hunted for himself, once, and so did not go to the daily feeding; later that day one of the small dragons brought up the grounds- master, Mr. Lloyd, and a surgeon, to be sure that he was not ill; and they lectured him on poaching sternly enough to make him uneasy for Laurence’s sake.

For all that, Lloyd did not think of him as a traitor, either; did not think enough of him to consider him one. The grounds-master only cared about his charges so far as they all stayed inside the borders, and ate, and mated; he recognized neither dignity nor stoicism, and anything which Temeraire did out of the ordinary was only a bit of fussing. “Come now, we have a fresh lady Anglewing visiting to-day,” Lloyd would say, jocularly, “quite a nice little piece; we will have a fine evening, eh? Perhaps we would like a bite of veal, first? Yes, we would, I am sure,” providing the responses with the questions, so Temeraire had nothing to do but sit and listen; and as Lloyd was a little hard of hearing, if Temeraire did try to say, “No, I would rather have some venison, and you might roast it first,” he was sure to be ignored.

It was almost enough to put one off making eggs, and in any case Temeraire was growing uncomfortably sure that his mother would not have approved in the least, how often they wished him to try, and how indiscriminately. Lien would certainly have sniffed in the most insulting way. It was not the fault of the female dragons sent to visit him, they were all very pleasant, but most of them had never managed an egg before, and some had never even been in a real battle or done anything interesting at all. So then they were embarrassed, as they did not have any suitable present for him which might have made up for it; and it was not as though he could pretend that he was not a very remarkable dragon, even if he liked to. Which he did not, very much, although he would have tried for Bellusa, a poor young Malachite Reaper without a single action to her name, sent by the Admiralty from Edinburgh, who miserably offered him a small knotted rug, which was all her confused captain would afford: it might have made a blanket for Temeraire’s largest talon.

“It is very handsome,” Temeraire said awkwardly, “and so cleverly done; I admire the colors very much,” and tried to drape it carefully over a small rock, by the entrance, but the gesture only made her look more wretched, and she burst out, “Oh, I do beg your pardon; he wouldn’t understand in the least, and thought I meant I would not like to, and then he said—” and she stopped abruptly in even worse confusion; so Temeraire was sure that whatever her captain had said, it had not been at all nice. It was as painful as could be, and he had not even the satisfaction of delivering one of his cherished retorts, because it was not as though she herself had said anything rude. So he did not much want to, but he obliged anyway. He was determined he would be patient, and quiet, in all things; he would not cause any trouble. He would be perfectly good.

Temeraire did not let himself think very much about Laurence; he did not trust himself. It was hard to endure the perpetual sensation of deep unease, almost overpowering, when he thought how he did not know how Laurence was, what his condition might be. Temeraire was sure to know every moment where his breastplate was, and his small gold chain, these being in his own possession; his talon-sheaths had been left with Emily, and he was quite certain she was to be trusted to keep them safe. Ordinarily he would have trusted Laurence, too, to keep himself safe; at least, if he were not proposing to do something dangerous for no very good reason, which he was sadly given to, on occasion; but the circumstances were not what they ought to be, and it had been so very long. The Admiralty had promised that so long as he behaved, Laurence would not be hanged, but they were not to be trusted, not at all. Temeraire resolved twice a week that he should go to Dover at once, to London—only to make inquiries, to see they had not, only to be sure—but unwanted reason always asserted itself, before he had even set out. He must not do anything which should persuade the Government he was unmanageable, and therefore Laurence of no use to them. He must be as complaisant and accommodating as ever he might.

It was a resolution already sorely tried by the end of his third week, when Lloyd brought him a visitor, admonishing the gentleman loudly, “Remember now, not to upset the dear creature, but to speak nice and slow and gentle, like to a horse,” infuriating enough, even before the gentleman was named to him as one Reverend Daniel Salcombe.

“Oh, you,” Temeraire said, which made that gentleman look aback, “yes, I know perfectly well who you are; I have read your very stupid letter to the Royal Society, and I suppose you are come to see me behave like a parrot, or a dog.”

Salcombe stammered excuses, but it was plainly the case; he began laboriously to read to Temeraire off a prepared list of questions, something quite nonsensical about predestination, but Temeraire would have none of it. “Pray be quiet; Saint Augustine explained it much better than you, and it still did not make any sense even then. Anyway, I am not going to perform for you, like a circus animal. I really cannot be bothered to speak to anyone so uneducated he has not read the Analects,” he added, guiltily excepting Laurence, in the back of his mind; but then Laurence did not set himself up as a scholar, and write insulting letters about people he did not know. “And as for dragons not understanding mathematics, I am sure I know more of it than do you.”

He scratched out with his claw a triangle, in the dirt, and labeled the two shorter sides. “There; tell me the length of the third, and then you may talk; otherwise, go away, and stop pretending you know anything about dragons.”

The simple diagramme had perplexed several gentlemen, when Temeraire had put it to them at a party in the London covert, rather disillusioning Temeraire as to the general understanding of mathematics among men. The Reverend Salcombe evidently had not paid much attention to that part of his education, either, for he stared, and colored up to his mostly bare pate, and turned to Lloyd furiously, saying, “You have put the creature up to this, I suppose! You prepared the remarks—” The unlikelihood of this accusation striking him, perhaps, as soon as he had made it to Lloyd’s gaping, uncomprehending face, he immediately amended, “They were given you, by someone, and you fed them to him, to embarrass me—”

“I never, sir,” Lloyd protested, to no avail, and it annoyed Temeraire so much that he nearly indulged himself in a small, a very small roar; but in the last moment he exercised great restraint, and only growled. Salcombe fled hastily all the same, Lloyd running after him, calling anxiously for the loss of his tip: he had been paid, then, to let Salcombe come and gawk at Temeraire, as though he really were a circus animal; and Temeraire was only sorry he had not roared, or better yet thrown them both in the lake.

And then his temper faded, and he drooped. He thought, too

late, that perhaps he ought to have talked to Salcombe, after all.

Lloyd would not read to him, or even tell him anything of the world

at all, even if Temeraire asked slowly and clearly enough to be understood,

but only said maddeningly, “Now, let’s not be worrying

ourselves about such things, no sense in getting worked up.” Salcombe,

however ignorant, had wished to have a conversation; and

he might yet have been prevailed upon to read him something from

the latest Proceedings, or a newspaper—oh, what Temeraire would

have done for a newspaper!

All this time the heavy-weight dragons had been finishing their

own dinners; the largest, a big Regal Copper, spat out a wellchewed

grey and bloodstained ball of fleece, belched tremendously,

and lifted away for his cave. His departure cleared a wide space of

the field, and now the rest came in a rush, middle-weights and lightweights

and the smaller courier-weight beasts landing in to take

their own share of the sheep and cattle, calling to one another noisily.

Temeraire did not move, but only hunched himself a little deeper

while they squabbled and played around him, and did not look up

even when one, a middle-weight with narrow blue-green legs, set

herself directly before him to eat, crunching loudly upon sheep

bones.

“I have been considering the matter,” she informed him, after a

little while, around a mouthful, “and in all cases, where the angle is

ninety degrees, as I suppose you meant to draw it, the length of the

longest side must be a number which, multiplied by itself, is equal

to the lengths of the two shorter sides, each multiplied by themselves,

added.” She swallowed noisily, and licked her chops clean.

“Quite an interesting little observation; how did you come to make

it?”

“I never,” Temeraire muttered. “It is the Pythagorean theorem;

everyone knows it who is educated. Laurence taught it me,” he

added, by way of making himself even more miserable.

“Hmh,” the other dragon said, rather haughtily, and flew away.

But she reappeared at Temeraire’s cave the next morning, uninvited,

and poked him awake with her nose, saying, “Perhaps you

would be interested to learn that there is a formula which I have invented,

which can invariably calculate the power of any sum; what

does Pythagoras have to say to that.”

“You never invented it,” Temeraire said, irritable at having been

woken up early, with so empty a day to be faced. “That is the binomial

theorem, Yang Hui made it a very long time ago,” and he put

his head under his wing and tried to lose himself again in sleep.

He thought that would be all, but four days later, while he lay

by his lake, the strange dragon landed beside him bristling and announced

in a furious rush, her words nearly tumbling over one another

in the attempt to get them out, “There, I have just worked out

something quite new: the prime number coming in a particular position,

for instance the tenth prime, is always very near the value of

that position, multiplied by the exponent one must put on the number

p to get that same value—the number p,” she added, “being a

very curious number, which I have also discovered, and named after

myself—”

“Certainly not,” Temeraire said, rousing with comfortable contempt,

when he had made sense of what she was talking about.

“That is e, and you are talking of the natural logarithm, and as for

the rest, about prime numbers, it is all nonsense; only consider the

prime fifteen—” and then he paused, working out the value in his

head.

“You see,” she said, triumphantly, and after working out another

two dozen examples, Temeraire was forced to admit the irritating

stranger might indeed be correct.

“And you needn’t tell me that this Pythagoras invented it first,”

the other dragon added, chest puffed out hugely, “or Yang Hui, because

I have inquired, and no-one has ever heard of either of them;

they do not live in any of the coverts or breeding grounds, so you

may keep your tricks. I thought as much; who ever heard of a

dragon named anything like Yang Hui; nonsense.”

Temeraire was neither despondent nor tired enough, in the moment,

to forget how dreadfully bored he was, and so he was less inclined

to take offense. “He is not a dragon, either of them,” he said,

“and they are both dead anyway, for years and years; Pythagoras

was a Greek, and Yang Hui was from China.”

“Then how do you know they invented it?” she demanded, suspiciously.

“Laurence read it me,” Temeraire said. “Where did you learn

any of it, if not out of books?”

“I worked it out myself,” the dragon said. “There is nothing

much else to do, here.”

Her name was Perscitia. She was an experimental cross-breed of

a Malachite Reaper and a light-weight Pascal’s Blue, who had come

out rather larger, slower, and more nervous than the breeders had

hoped; and her coloring was not ideal for any sort of camouflage:

the body and wings mostly bright blue and streaked with shades of

pale green, with widely scattered spines along her back. She was not

very old, either, unlike most of the once-harnessed dragons in the

breeding grounds: she had given up her captain. “Well,” Perscitia

said, “I did not mind my captain, he showed me how to do equations,

when I was small, but I do not see any use in going to war,

and getting oneself shot at or clawed up, for no reason which anyone

could explain to me. And, when I would not fight, he did not

much want me anymore,” a statement airily delivered, but Perscitia

avoided Temeraire’s eyes, making it.

“If you mean formation-fighting, I do not blame you; it is very

tiresome,” Temeraire said. “They do not approve of me in China,”

he added, to be sympathetic, “because I do fight: Celestials are not

supposed to.”

“China must be a very fine place,” Perscitia said, wistfully, and

Temeraire was by no means inclined to disagree; he thought sadly

that if only Laurence had been willing, they might now be together

in Peking, perhaps strolling in the gardens of the Summer Palace

again; he had not had the chance to see it in autumn.

And then he paused, and abruptly raising his head he said, “You

say you made inquiries: what do you mean by that? You cannot

have gone out.”

“Of course not,” Perscitia said. “I gave Moncey half my dinner,

and he went to Brecon for me and put the question out on the

courier circuit; this morning he went again, and the word was in noone

had ever heard of anybody by those names.”

“Oh—” Temeraire said, his ruff rising, “oh, pray; who is Moncey?

I will give him anything he likes, if only he can find out where

Laurence is; he may have all my dinner, for a week.”

Moncey was a Winchester, who had slipped the leash and eeled

right out the door of the barn where he had hatched, past a candidate

he did not care for, and so made his escape from the Corps. He

had been coaxed eventually into the breeding grounds, more by the

promise of company than anything else, being a gregarious creature.

Small and dark purplish, he looked like any other Winchester

at a distance, and excited no comment if either seen abroad or absent

from the daily feeding; and as long as his missed meals were

properly compensated for, he was very willing to oblige.

“Hm, how about you give me one of those cows, the nice fat

sort they save for you special, when you are mating,” Moncey said.

“I would like to give Laculla a proper treat,” he added, exultingly.

“Highway robbery,” Perscitia said indignantly, but Temeraire

did not care at all; he was learning in any case to hate the taste of

the cows, when it meant yet another miserably awkward evening

session, and nodded on the bargain.

“But no promises, mind,” Moncey cautioned. “I’ll put it about,

no fears, but it’ll be as many as a few weeks to hear back, if you

want it sorted out proper to all the coverts, and to Ireland, and even

so maybe no-one will have heard anything.”

“There is sure to have been word,” Temeraire said, low, “if he is

dead.”

the ball came in down through the ship’s bows and crashed

recklessly the length of the lower deck, the drumroll of its passage

preceding it with castanets of splinters raining against the walls for

accompaniment. The young Marine guarding the brig had been

trembling since the call to go to quarters had sounded above; a mingling,

Laurence thought, of anxiety and the desire to be doing something,

and the frustration at being kept at so useless and miserable

a post: a sentiment he shared from his still more useless place within

the cell. The ball seemed only to be rolling at a leisurely pace by the

time it approached the brig, and offered a first opportunity; the Marine

had put out his foot to stop it before Laurence could say a

word.

He had seen much the same impulse have much the same result

on other battlefields: the ball took off the better part of the foot and

continued unperturbed into and through the metal grating, skewing

the door off its top hinge and finally embedding itself two inches

deep into the solid oak wall of the ship, there remaining. Laurence

pushed the crazily swinging door open and climbed out of the brig,

taking off his neckcloth to tie the Marine’s foot; the young man was

staring amazed at the bloody stump, and needed a little coaxing to

limp along to the orlop. “A clean shot; I am sure the rest will come

off nicely,” Laurence said for comfort, and left him to the surgeons;

the steady roar of cannon-fire was going on overhead.

He went up the stern ladderway and plunged into the confusion

of the gundeck: daylight shining in from her east-pointed bows,

through jagged gaping holes, and making a glittering cloud of the

smoke and dust kicked up from the cannon. Roaring Martha had

jumped her tackling, and five men were fighting to hold her wedged

against the roll of the ship long enough to get her secure again; at

any moment the gun might go running wild across the deck, crushing

men and perhaps smashing through the side. “There girl, hold

fast, hold fast—” The captain of the gun-crew was speaking to her

like a skittish horse, his hands wincing away from the barrel,

smoking-hot; one side of his face was bristling with splinters standing

out like hedgehog spines.

In the smoke, in the red light, no one knew Laurence; he was

only another pair of hands. He had his flight gloves still in his coat

pocket; he clapped on to the metal with them and pushed her by the

mouth of the barrel, his palms stinging even through the thick

leather, and with a final thump she heaved over into the grooves

again. The men tied her down and then stood around her trembling

like well-run horses, panting and sweating.

There was no return firing, no calls passed along from the quarterdeck,

no ship in view through the gunport. The ship was griping

furiously where Laurence put his hand on the side, a sort of low

moaning complaint as if she were trying to go too close to the wind,

and water was glubbing in a curious way against her sides: a sound

wholly unfamiliar, and he knew this ship. He had served on Goliath

four years in her midshipmen’s mess as a boy, as lieutenant for another

two and at the Battle of the Nile; he would have said he could

recognize every note of her voice.

He put his head out the porthole and saw the enemy crossing

their bows and turning to come about for another pass: a frigate

only, a beautiful trim thirty-six-gun ship which could have thrown

not half of Goliath’s broadside; an absurd combat on the face of it,

and he could not understand why they had not turned to rake her

across the stern. Instead there was only a little grumbling from the

bow-chasers above, not much reply to be making. Looking forward

along the ship, he saw that she had been pierced by an enormous

harpoon sticking through her side, as if she were a whale. The end

inside the ship had several ingeniously curved barbs, which had

been jerked sharply back to dig into the wood; and the cable at the

harpoon’s other end swung grandly up and up and up, into the air,

where two enormous heavy-weight dragons were holding on to it:

an older Parnassian, likely traded to France during an earlier peacetime,

and a Grand Chevalier.

It was not the only harpoon: three more cable-lines dangled

down from their grip to the bow, and another two from the stern,

that Laurence could see. The dragons were too far aloft for him to

make out the details, with the ship’s motion underneath him, but

the cables were somehow laced into their harnesses, and merely by

flying together and pulling, they were pivoting the ship’s head into

the wind: all her sails must have been taken aback, and the dragons

were too far aloft for round-shot to reach them. One of them

sneezed from the action of the frantically speaking pepper guns, but

they had only to beat their wings a little more to get away from the

pepper, hauling the ship along while they did it.

“Axes, axes,” the lieutenant was shouting, with a clattering of

iron as the bosun’s mates came spilling weapons across the floor:

hand-axes, cutlasses, knives. The men snatched them up and began

to reach out the portholes to try and hack the ship free, but the harpoons

were two foot long from the hook, and the ropes had enough

slackness to give no good purchase to their efforts. Someone would

have to climb out of a porthole to saw at them: open and exposed

against the hull of the ship, with the frigate coming around again.

No-one moved to go, at first; then Laurence reached out and

took a short cutlass, sharpened, from the heap. The lieutenant

looked into his face and knew him, but said nothing. Turning to the

porthole, Laurence worked his shoulders through and pulled himself

out, many hands quickly coming beneath his feet to support

him and the lieutenant calling again; shortly a rope was flung down

to him from the deck above, so he could brace himself against the

hull. Many faces were peering over at him anxiously: strangers;

then another man came sliding down over the rail, and another, to

work on the other harpoons.

Laurence began the grim effort of sawing away at the cable,

strands going one at a time; the rope was cable-laid, three hawsers

of three strands, well-wormed and thick as a man’s wrist and

parceled in canvas, and meanwhile he made a bright target against

the ship’s paintwork for the guns of the frigate. If he were killed, the

embarrassment of his hanging would at least be spared his family.

He was only alive now to be a chain round Temeraire’s neck, until

the Admiralty should decide the dragon pacified enough by age and

habit that Laurence might be dispensed with and his sentence carried

out; and that might be years, long years, mouldering in gaol or

in the bowels of a ship.

It was not a purposeful thought, no guilty intention; it only

crossed his mind involuntarily, while he worked. He had his back to

the ocean and could not see anything of the frigate or the larger battle

beyond: his horizon was the splintered paint of Goliath’s side,

lacquered shine made rough by splinters and salt, and the cold sea

was climbing up her hull and spraying his back. Distant roars of

cannon-fire spoke, but Goliath had let her guns fall silent, saving

her powder and shot for when they should be of some use. The

loudest noises in his ears were the grunts and effort of the men

hanging nearby, sawing at their own harpoon-lines. Then one of

them gave a startled yell and let go his rope, falling away into the

churning ocean; a small darting courier-beast, a Chasseur-Vocifère,

was plunging at the side of the ship with another harpoon.

The beast held it something like a jouster in a medieval tournament,

with the butt rigged awkwardly into a cup attached to its harness,

for support, and two men on its back bracing the rig. The

harpoon thumped dully against the ship’s side, near to where Laurence

hung, and the dragon’s tail slapped a wash of salt water up

into his face, heavy stinging thickness in his nostrils and dripping

down the back of his throat as he choked it out. The dragon lunged

away again even as the Marines fired off a furious volley, trailing

the harpoon on its line behind it: the barb had not bitten deep

enough to penetrate. The hull was pockmarked with the dents of

earlier attempts, a good dozen for each planted harpoon marring

her spit-and-polish paintwork.

Laurence wiped salt from his face against his arm and shouted,

“Keep working, man, damn you,” at the other seaman still hanging

near him. The first rope of his own cable was gone at last, tough fibres

fraying away from the cutlass edge and fanning out like a

broom; he began on the second, rapidly, although the blade was

going dull.

The frigate was still there to harass them, and he could not help

but look around at the roar of cannon so nearby. A ball came

whistling across the water, skipping two, three times along the

wave-tops, like a stone thrown by a boy. It looked as though it came

straight for him, an illusion: the whole ship groaned as the ball

punched in at the bows, and splinters flew like a sudden blizzard

out of the open portholes. They peppered Laurence’s legs, stinging

like a flock of bees, and his stockings were quickly wet with blood.

He clung on to the harpoon arm and kept sawing; the frigate was

still firing, broadside rolling on, and the round-shot hurtled at them

again and again, a sickening deep sway to Goliath’s motion now as

she took the pounding.

He had to hand the cutlass back in and shout for a fresh to get

through the last strand; then at last the cable was cut loose and

swinging away free, and they pulled him back in; he staggered when

he tried to stand, and went to his knees slipping in blood: stockings

laddered and soaked through red; his best breeches, still the same

ones he had worn for the trial, were pierced and spotted. He was

helped to sit against the wall, and turned the cutlass on his own

shirt for bandages to tie up the worst of the gashes; no-one could be

spared to help him to the surgeons. The other harpoons had been

cut; they were moving at last, coming around; and all the crews

were fixed by their guns, savage in the dim red glow penetrating,

teeth bared and mazed with blood from cracked lips and gums,

faces black with sweat and grime, ready to take vengeance.

A loud pattering like rain or hailstones came suddenly down:

small bombs with short fuses dropped by the French dragons,

flashes like lightning visible through the boards of the deck; some

rolled down through the ladderways and burst in the gundeck, hot

flash-powder smoke and the burning glare of pyrotechnics, painful

to the eyes; then they hove around in view of the frigate and the

order came down to fire, fire.

There was nothing for a long moment but the mindless fury of

the ship’s guns going: impossible to think in that roaring din, smoke

and hellish fire in her bowels choking away all reason. Laurence

reached up for the porthole when they had paused, and hauled himself

up to look. The French frigate was reeling away under the

pounding, her foremast down and hulled below the water-line, so

each wave slapping away poured into her.

There was no cheering. Past the retreating frigate, the breadth of

the Channel spread open before them, and all the great ships of the

blockade, entangled and harassed just as they had been. The

Aboukir and the mighty Sultan, seventy-four guns, were near

enough to recognize: cables rising up to three and four dragons,

French heavy-weights and middle-weights industriously tugging

every which way. The ships were firing steadily but uselessly, clouds

of smoke that did not reach the dragons above.

And between them, half-a-dozen French ships-of-the-line, come

out of harbor at last, were stately going by, escort to an enormous

flotilla. A hundred and more, barges and fishing-boats and even

rafts in lateen rig, all of them crammed with soldiers, the wind at

their backs and the tide carrying them towards the shore, tricolors

streaming proudly from their bows towards England.

With the Navy paralyzed, only the dragons of the Corps were

left to stop the advance. But the French warships were firing regularly

into the air above the flotilla: something like pepper, in vaster

quantities than could have been afforded of spice, and burning. Red

spark fragments glowed like fireflies against the black smoke-cloud

which hung over the boats, shielding them from aerial attack. One

of the transport boats was near enough that Laurence saw the men

had their faces covered with wet kerchiefs and rags, or huddled

under oilcloth sheets. The British dragons made desperate attempts

to dive, but recoiled from the clouds, and had instead to fling down

bombs from too great a height: ten splashing into the wide ocean

for every one which came near enough to make a wave against a

ship’s hull. The smaller French dragons harried them, too, flying

back and forth and jeering in shrill voices. There were so many of

them, Laurence had never seen so many: wheeling almost like birds,

clustering and breaking apart, offering no easy target to the British

dragons in their stately formations.

One great Regal Copper might have been Maximus: red and orange

and yellow against the blue sky, at the head of a formation

with Yellow Reapers in two lines to his either wing, but Laurence

did not see Lily. The Regal roared, audible faintly even over the distance,

and bulled his formation through a dozen French lightweights

to come at a great French warship: flames bloomed from

her sails as the bombs at last hit, but when the formation rose away

again, one of the Reapers was streaming crimson from its belly and

another was listing. A handful of British frigates, too, were valiantly

trying to dash past the French ships to come at the transports: with

some little success, but they were under heavy fire, and if they sank

a dozen boats, half the men were pulled aboard others, so close

were the little transports to one another.

“Every man to his gun,” the lieutenant said sharply. Goliath

was turning to go after the transports. She would be passing between

Majestueux and Héros, a broadside of nearly three tons between

them. Laurence felt it when her sails caught the wind

properly again: the ship leaping forward like an eager racehorse

held too long. She had made all sail. He touched his leg: the blood

had stopped flowing, he thought. He limped back to an empty place

at a gun.

Outside, the first transports were already hurtling themselves

onward to the shore, light-weight dragons wheeling above to shield

them while they ran artillery onto the ground, and one soldier

rammed the standard into the dirt, the golden eagle atop catching

fire with the sunlight: Napoleon had landed in England at last.

From the Hardcover edition.

The breeding grounds were called Pen Y Fan, after the hard, jagged slash of the mountain at their heart, like an ax-blade, rimed with ice along its edge and rising barren over the moorlands: a cold, wet Welsh autumn already, coming on towards winter, and the other dragons sleepy and remote, uninterested in anything but their meals. There were a few hundred of them scattered throughout the grounds, mostly established in caves or on rocky ledges, wherever they could fit themselves; nothing of comfort or even order provided for them, except the feedings, and the mowed-bare strip of dirt around the borders, where torches were lit at night to mark the lines past which they might not go, with the town-lights glimmering in the distance, cheerful and forbidden.

Temeraire had hunted out and cleared a large cavern, on his arrival, to sleep in; but it would be damp, no matter what he did in the way of lining it with grass, or flapping his wings to move the air, which in any case did not suit his instinctive notions of dignity: much better to endure every unpleasantness with stoic patience, although that was not very satisfying when no-one would appreciate the effort. The other dragons certainly did not.

He was quite sure he and Laurence had done as they ought, in taking the cure to France, and no-one sensible could disagree; but just in case, Temeraire had steeled himself to meet with either disapproval or contempt, and he had worked out several very fine arguments in his defense. Most importantly, of course, it was just a cowardly, sneaking way of fighting: if the Government wished to beat Napoleon, they ought to fight him directly, and not make his dragons sick to try and make him easy to defeat; as if British dragons could not beat French dragons, without cheating. “And not only that,” he added, “but it would not be only the French dragons who died: our friends from Prussia who are imprisoned in their breeding grounds would also have got sick, and perhaps it might even have gone so far as China; and that would be like stealing someone else’s food, even when you are not hungry; or breaking their eggs.”

He made this impressive speech to the wall of his cave, as practice: they had refused to give him his sand-table, and he had no-one of his crew to jot it down for him, either; he did not have Laurence, who would have helped him work out just what to say. So he repeated the arguments over to himself quietly, instead, so he should not forget them. And if these should not suffice to persuade, he thought, he might point out that after all, he had brought the cure back, in the first place: he and Laurence, with Maximus and Lily and the rest of their formation, and if anyone had a right to say where it should be shared out, they did: no-one would even have known of it if Temeraire had not contrived to be sick in Africa, where the mushrooms which cured it grew.

He might have saved the trouble. No-one accused him of anything, nor, as he had privately, a little wistfully, thought just barely possible, hailed him as a hero; because they did not care.

The older dragons, not feral but retired, were a little curious about the latest developments in the war, but only distantly, more inclined to tell over their own battles of earlier wars; and the rest had plenty of indignation over the recent epidemic, but only in a provincial way. They cared that they and their own fellows had sickened and died; they cared that the cure had taken so long to reach them; but it did not mean anything to them that dragons in France had also been ill, or that the disease would have spread, killing thousands, if Temeraire and Laurence had not taken over the cure; they also did not care that the Lords of the Admiralty had called it treason, and sentenced Laurence to die.

They had nothing to care for. They were fed, and there was enough for everyone. If the shelter was not pleasant, it was no worse than what even the retired dragons were used to, from the days of their active service; they had none of them even heard of a pavilion, or thought they might be made more comfortable than they were. No-one ever molested an egg; the grounds-keepers would take them away, but with infinite care, in waggons lined with straw, hot-water bottles and woolen blankets in the wintertime; and they would bring back reports until the eggs were hatched and no more of anyone’s concern; so everyone knew the eggs were safe in their hands; safer, even, than keeping them oneself, so even the dragons who had not cared to take a captain themselves, at all, would often as not hand over their own eggs. They could not go flying very far, because they were fed at no set time but randomly, from day to day, so if one went away out of ear-shot of the bells, one was likely to come too late, and go hungry all the day. So there was no larger society, no intercourse with the other breeding grounds or with the coverts, except when some other dragon came from afar, to mate; even that was arranged for them. Instead they sat, willing prisoners in their own territory, Temeraire thought bitterly; he would never have endured it if not for Laurence, only for Laurence, who would surely be put to death at once if Temeraire did not obey.

He held himself aloof from their society at first. There was his cave to be arranged: despite its fine prospect it had been left vacant for being inconveniently shallow, and he was rather crammed-in; but there was a much larger chamber beyond, visible through holes in the back wall, which he gradually opened up with the slow and cautious use of his roar. Slower, even, than perhaps necessary—he was very willing to have the task consume several days. The cave had then to be cleared of debris, old gnawed bones and inconvenient boulders, which he scraped out painstakingly even from the corners too small for him to lie in, for neatness’ sake; and he found a few rough boulders in the valley and used them to grind the cave walls a little smoother, by dragging them back and forth, throwing up a great cloud of dust.

It made him sneeze, but he kept on; he was not going to live in a raw untidy hole. He knocked down stalactites from the ceiling, and beat protrusions flat into the floor, and when he was satisfied, he arranged along the sides of what was now his antechamber, with careful nudges of his talons, some attractive rocks and old, dead tree-branches, twisted and bleached white, which he had collected from the woods and ravines. He would have liked a pond and a fountain, but he could not see how to bring the water up, or how to make it run when he had got it there, so he settled for picking out a promontory on Llyn y Fan Fawr which jutted into the lake, and considering it also his own.

To finish he carved the characters of his name into the cliff face by the entrance, and also in English, although the letter R gave him some difficulty and came out looking rather like the reversed numeral 4; then he was done with that, and routine crept up and devoured his days. To rise, when the sun came in at the cave-mouth; to take a little exercise, to nap, to rise again when the herdsmen rang the bell, to eat, then to nap and to exercise again, and then back to sleep; and that was the end of the day, there was nothing more. He hunted for himself, once, and so did not go to the daily feeding; later that day one of the small dragons brought up the grounds- master, Mr. Lloyd, and a surgeon, to be sure that he was not ill; and they lectured him on poaching sternly enough to make him uneasy for Laurence’s sake.

For all that, Lloyd did not think of him as a traitor, either; did not think enough of him to consider him one. The grounds-master only cared about his charges so far as they all stayed inside the borders, and ate, and mated; he recognized neither dignity nor stoicism, and anything which Temeraire did out of the ordinary was only a bit of fussing. “Come now, we have a fresh lady Anglewing visiting to-day,” Lloyd would say, jocularly, “quite a nice little piece; we will have a fine evening, eh? Perhaps we would like a bite of veal, first? Yes, we would, I am sure,” providing the responses with the questions, so Temeraire had nothing to do but sit and listen; and as Lloyd was a little hard of hearing, if Temeraire did try to say, “No, I would rather have some venison, and you might roast it first,” he was sure to be ignored.

It was almost enough to put one off making eggs, and in any case Temeraire was growing uncomfortably sure that his mother would not have approved in the least, how often they wished him to try, and how indiscriminately. Lien would certainly have sniffed in the most insulting way. It was not the fault of the female dragons sent to visit him, they were all very pleasant, but most of them had never managed an egg before, and some had never even been in a real battle or done anything interesting at all. So then they were embarrassed, as they did not have any suitable present for him which might have made up for it; and it was not as though he could pretend that he was not a very remarkable dragon, even if he liked to. Which he did not, very much, although he would have tried for Bellusa, a poor young Malachite Reaper without a single action to her name, sent by the Admiralty from Edinburgh, who miserably offered him a small knotted rug, which was all her confused captain would afford: it might have made a blanket for Temeraire’s largest talon.

“It is very handsome,” Temeraire said awkwardly, “and so cleverly done; I admire the colors very much,” and tried to drape it carefully over a small rock, by the entrance, but the gesture only made her look more wretched, and she burst out, “Oh, I do beg your pardon; he wouldn’t understand in the least, and thought I meant I would not like to, and then he said—” and she stopped abruptly in even worse confusion; so Temeraire was sure that whatever her captain had said, it had not been at all nice. It was as painful as could be, and he had not even the satisfaction of delivering one of his cherished retorts, because it was not as though she herself had said anything rude. So he did not much want to, but he obliged anyway. He was determined he would be patient, and quiet, in all things; he would not cause any trouble. He would be perfectly good.

Temeraire did not let himself think very much about Laurence; he did not trust himself. It was hard to endure the perpetual sensation of deep unease, almost overpowering, when he thought how he did not know how Laurence was, what his condition might be. Temeraire was sure to know every moment where his breastplate was, and his small gold chain, these being in his own possession; his talon-sheaths had been left with Emily, and he was quite certain she was to be trusted to keep them safe. Ordinarily he would have trusted Laurence, too, to keep himself safe; at least, if he were not proposing to do something dangerous for no very good reason, which he was sadly given to, on occasion; but the circumstances were not what they ought to be, and it had been so very long. The Admiralty had promised that so long as he behaved, Laurence would not be hanged, but they were not to be trusted, not at all. Temeraire resolved twice a week that he should go to Dover at once, to London—only to make inquiries, to see they had not, only to be sure—but unwanted reason always asserted itself, before he had even set out. He must not do anything which should persuade the Government he was unmanageable, and therefore Laurence of no use to them. He must be as complaisant and accommodating as ever he might.

It was a resolution already sorely tried by the end of his third week, when Lloyd brought him a visitor, admonishing the gentleman loudly, “Remember now, not to upset the dear creature, but to speak nice and slow and gentle, like to a horse,” infuriating enough, even before the gentleman was named to him as one Reverend Daniel Salcombe.

“Oh, you,” Temeraire said, which made that gentleman look aback, “yes, I know perfectly well who you are; I have read your very stupid letter to the Royal Society, and I suppose you are come to see me behave like a parrot, or a dog.”

Salcombe stammered excuses, but it was plainly the case; he began laboriously to read to Temeraire off a prepared list of questions, something quite nonsensical about predestination, but Temeraire would have none of it. “Pray be quiet; Saint Augustine explained it much better than you, and it still did not make any sense even then. Anyway, I am not going to perform for you, like a circus animal. I really cannot be bothered to speak to anyone so uneducated he has not read the Analects,” he added, guiltily excepting Laurence, in the back of his mind; but then Laurence did not set himself up as a scholar, and write insulting letters about people he did not know. “And as for dragons not understanding mathematics, I am sure I know more of it than do you.”

He scratched out with his claw a triangle, in the dirt, and labeled the two shorter sides. “There; tell me the length of the third, and then you may talk; otherwise, go away, and stop pretending you know anything about dragons.”

The simple diagramme had perplexed several gentlemen, when Temeraire had put it to them at a party in the London covert, rather disillusioning Temeraire as to the general understanding of mathematics among men. The Reverend Salcombe evidently had not paid much attention to that part of his education, either, for he stared, and colored up to his mostly bare pate, and turned to Lloyd furiously, saying, “You have put the creature up to this, I suppose! You prepared the remarks—” The unlikelihood of this accusation striking him, perhaps, as soon as he had made it to Lloyd’s gaping, uncomprehending face, he immediately amended, “They were given you, by someone, and you fed them to him, to embarrass me—”

“I never, sir,” Lloyd protested, to no avail, and it annoyed Temeraire so much that he nearly indulged himself in a small, a very small roar; but in the last moment he exercised great restraint, and only growled. Salcombe fled hastily all the same, Lloyd running after him, calling anxiously for the loss of his tip: he had been paid, then, to let Salcombe come and gawk at Temeraire, as though he really were a circus animal; and Temeraire was only sorry he had not roared, or better yet thrown them both in the lake.

And then his temper faded, and he drooped. He thought, too

late, that perhaps he ought to have talked to Salcombe, after all.

Lloyd would not read to him, or even tell him anything of the world

at all, even if Temeraire asked slowly and clearly enough to be understood,

but only said maddeningly, “Now, let’s not be worrying

ourselves about such things, no sense in getting worked up.” Salcombe,

however ignorant, had wished to have a conversation; and

he might yet have been prevailed upon to read him something from

the latest Proceedings, or a newspaper—oh, what Temeraire would

have done for a newspaper!

All this time the heavy-weight dragons had been finishing their

own dinners; the largest, a big Regal Copper, spat out a wellchewed

grey and bloodstained ball of fleece, belched tremendously,

and lifted away for his cave. His departure cleared a wide space of

the field, and now the rest came in a rush, middle-weights and lightweights

and the smaller courier-weight beasts landing in to take

their own share of the sheep and cattle, calling to one another noisily.

Temeraire did not move, but only hunched himself a little deeper

while they squabbled and played around him, and did not look up

even when one, a middle-weight with narrow blue-green legs, set

herself directly before him to eat, crunching loudly upon sheep

bones.

“I have been considering the matter,” she informed him, after a

little while, around a mouthful, “and in all cases, where the angle is

ninety degrees, as I suppose you meant to draw it, the length of the

longest side must be a number which, multiplied by itself, is equal

to the lengths of the two shorter sides, each multiplied by themselves,

added.” She swallowed noisily, and licked her chops clean.

“Quite an interesting little observation; how did you come to make

it?”

“I never,” Temeraire muttered. “It is the Pythagorean theorem;

everyone knows it who is educated. Laurence taught it me,” he

added, by way of making himself even more miserable.

“Hmh,” the other dragon said, rather haughtily, and flew away.

But she reappeared at Temeraire’s cave the next morning, uninvited,

and poked him awake with her nose, saying, “Perhaps you

would be interested to learn that there is a formula which I have invented,

which can invariably calculate the power of any sum; what

does Pythagoras have to say to that.”

“You never invented it,” Temeraire said, irritable at having been

woken up early, with so empty a day to be faced. “That is the binomial

theorem, Yang Hui made it a very long time ago,” and he put

his head under his wing and tried to lose himself again in sleep.

He thought that would be all, but four days later, while he lay

by his lake, the strange dragon landed beside him bristling and announced

in a furious rush, her words nearly tumbling over one another

in the attempt to get them out, “There, I have just worked out

something quite new: the prime number coming in a particular position,

for instance the tenth prime, is always very near the value of

that position, multiplied by the exponent one must put on the number

p to get that same value—the number p,” she added, “being a

very curious number, which I have also discovered, and named after

myself—”

“Certainly not,” Temeraire said, rousing with comfortable contempt,

when he had made sense of what she was talking about.

“That is e, and you are talking of the natural logarithm, and as for

the rest, about prime numbers, it is all nonsense; only consider the

prime fifteen—” and then he paused, working out the value in his

head.

“You see,” she said, triumphantly, and after working out another

two dozen examples, Temeraire was forced to admit the irritating

stranger might indeed be correct.

“And you needn’t tell me that this Pythagoras invented it first,”

the other dragon added, chest puffed out hugely, “or Yang Hui, because

I have inquired, and no-one has ever heard of either of them;

they do not live in any of the coverts or breeding grounds, so you

may keep your tricks. I thought as much; who ever heard of a

dragon named anything like Yang Hui; nonsense.”

Temeraire was neither despondent nor tired enough, in the moment,

to forget how dreadfully bored he was, and so he was less inclined

to take offense. “He is not a dragon, either of them,” he said,

“and they are both dead anyway, for years and years; Pythagoras

was a Greek, and Yang Hui was from China.”

“Then how do you know they invented it?” she demanded, suspiciously.

“Laurence read it me,” Temeraire said. “Where did you learn

any of it, if not out of books?”

“I worked it out myself,” the dragon said. “There is nothing

much else to do, here.”

Her name was Perscitia. She was an experimental cross-breed of

a Malachite Reaper and a light-weight Pascal’s Blue, who had come

out rather larger, slower, and more nervous than the breeders had

hoped; and her coloring was not ideal for any sort of camouflage:

the body and wings mostly bright blue and streaked with shades of

pale green, with widely scattered spines along her back. She was not

very old, either, unlike most of the once-harnessed dragons in the

breeding grounds: she had given up her captain. “Well,” Perscitia

said, “I did not mind my captain, he showed me how to do equations,

when I was small, but I do not see any use in going to war,

and getting oneself shot at or clawed up, for no reason which anyone

could explain to me. And, when I would not fight, he did not

much want me anymore,” a statement airily delivered, but Perscitia

avoided Temeraire’s eyes, making it.

“If you mean formation-fighting, I do not blame you; it is very

tiresome,” Temeraire said. “They do not approve of me in China,”

he added, to be sympathetic, “because I do fight: Celestials are not

supposed to.”

“China must be a very fine place,” Perscitia said, wistfully, and

Temeraire was by no means inclined to disagree; he thought sadly

that if only Laurence had been willing, they might now be together

in Peking, perhaps strolling in the gardens of the Summer Palace

again; he had not had the chance to see it in autumn.

And then he paused, and abruptly raising his head he said, “You

say you made inquiries: what do you mean by that? You cannot

have gone out.”

“Of course not,” Perscitia said. “I gave Moncey half my dinner,

and he went to Brecon for me and put the question out on the

courier circuit; this morning he went again, and the word was in noone

had ever heard of anybody by those names.”

“Oh—” Temeraire said, his ruff rising, “oh, pray; who is Moncey?

I will give him anything he likes, if only he can find out where

Laurence is; he may have all my dinner, for a week.”

Moncey was a Winchester, who had slipped the leash and eeled

right out the door of the barn where he had hatched, past a candidate

he did not care for, and so made his escape from the Corps. He

had been coaxed eventually into the breeding grounds, more by the

promise of company than anything else, being a gregarious creature.

Small and dark purplish, he looked like any other Winchester

at a distance, and excited no comment if either seen abroad or absent

from the daily feeding; and as long as his missed meals were

properly compensated for, he was very willing to oblige.

“Hm, how about you give me one of those cows, the nice fat

sort they save for you special, when you are mating,” Moncey said.

“I would like to give Laculla a proper treat,” he added, exultingly.

“Highway robbery,” Perscitia said indignantly, but Temeraire

did not care at all; he was learning in any case to hate the taste of

the cows, when it meant yet another miserably awkward evening

session, and nodded on the bargain.

“But no promises, mind,” Moncey cautioned. “I’ll put it about,

no fears, but it’ll be as many as a few weeks to hear back, if you

want it sorted out proper to all the coverts, and to Ireland, and even

so maybe no-one will have heard anything.”

“There is sure to have been word,” Temeraire said, low, “if he is

dead.”

the ball came in down through the ship’s bows and crashed

recklessly the length of the lower deck, the drumroll of its passage

preceding it with castanets of splinters raining against the walls for

accompaniment. The young Marine guarding the brig had been

trembling since the call to go to quarters had sounded above; a mingling,

Laurence thought, of anxiety and the desire to be doing something,

and the frustration at being kept at so useless and miserable

a post: a sentiment he shared from his still more useless place within

the cell. The ball seemed only to be rolling at a leisurely pace by the

time it approached the brig, and offered a first opportunity; the Marine

had put out his foot to stop it before Laurence could say a

word.

He had seen much the same impulse have much the same result

on other battlefields: the ball took off the better part of the foot and

continued unperturbed into and through the metal grating, skewing

the door off its top hinge and finally embedding itself two inches

deep into the solid oak wall of the ship, there remaining. Laurence

pushed the crazily swinging door open and climbed out of the brig,

taking off his neckcloth to tie the Marine’s foot; the young man was

staring amazed at the bloody stump, and needed a little coaxing to

limp along to the orlop. “A clean shot; I am sure the rest will come

off nicely,” Laurence said for comfort, and left him to the surgeons;

the steady roar of cannon-fire was going on overhead.

He went up the stern ladderway and plunged into the confusion

of the gundeck: daylight shining in from her east-pointed bows,

through jagged gaping holes, and making a glittering cloud of the

smoke and dust kicked up from the cannon. Roaring Martha had

jumped her tackling, and five men were fighting to hold her wedged

against the roll of the ship long enough to get her secure again; at

any moment the gun might go running wild across the deck, crushing

men and perhaps smashing through the side. “There girl, hold

fast, hold fast—” The captain of the gun-crew was speaking to her

like a skittish horse, his hands wincing away from the barrel,

smoking-hot; one side of his face was bristling with splinters standing

out like hedgehog spines.

In the smoke, in the red light, no one knew Laurence; he was

only another pair of hands. He had his flight gloves still in his coat

pocket; he clapped on to the metal with them and pushed her by the

mouth of the barrel, his palms stinging even through the thick

leather, and with a final thump she heaved over into the grooves

again. The men tied her down and then stood around her trembling

like well-run horses, panting and sweating.

There was no return firing, no calls passed along from the quarterdeck,

no ship in view through the gunport. The ship was griping

furiously where Laurence put his hand on the side, a sort of low

moaning complaint as if she were trying to go too close to the wind,

and water was glubbing in a curious way against her sides: a sound

wholly unfamiliar, and he knew this ship. He had served on Goliath

four years in her midshipmen’s mess as a boy, as lieutenant for another

two and at the Battle of the Nile; he would have said he could

recognize every note of her voice.

He put his head out the porthole and saw the enemy crossing

their bows and turning to come about for another pass: a frigate

only, a beautiful trim thirty-six-gun ship which could have thrown

not half of Goliath’s broadside; an absurd combat on the face of it,

and he could not understand why they had not turned to rake her

across the stern. Instead there was only a little grumbling from the

bow-chasers above, not much reply to be making. Looking forward

along the ship, he saw that she had been pierced by an enormous

harpoon sticking through her side, as if she were a whale. The end

inside the ship had several ingeniously curved barbs, which had

been jerked sharply back to dig into the wood; and the cable at the

harpoon’s other end swung grandly up and up and up, into the air,

where two enormous heavy-weight dragons were holding on to it:

an older Parnassian, likely traded to France during an earlier peacetime,

and a Grand Chevalier.

It was not the only harpoon: three more cable-lines dangled

down from their grip to the bow, and another two from the stern,

that Laurence could see. The dragons were too far aloft for him to

make out the details, with the ship’s motion underneath him, but

the cables were somehow laced into their harnesses, and merely by

flying together and pulling, they were pivoting the ship’s head into

the wind: all her sails must have been taken aback, and the dragons

were too far aloft for round-shot to reach them. One of them

sneezed from the action of the frantically speaking pepper guns, but

they had only to beat their wings a little more to get away from the

pepper, hauling the ship along while they did it.

“Axes, axes,” the lieutenant was shouting, with a clattering of

iron as the bosun’s mates came spilling weapons across the floor:

hand-axes, cutlasses, knives. The men snatched them up and began

to reach out the portholes to try and hack the ship free, but the harpoons

were two foot long from the hook, and the ropes had enough

slackness to give no good purchase to their efforts. Someone would

have to climb out of a porthole to saw at them: open and exposed

against the hull of the ship, with the frigate coming around again.

No-one moved to go, at first; then Laurence reached out and

took a short cutlass, sharpened, from the heap. The lieutenant

looked into his face and knew him, but said nothing. Turning to the

porthole, Laurence worked his shoulders through and pulled himself

out, many hands quickly coming beneath his feet to support

him and the lieutenant calling again; shortly a rope was flung down

to him from the deck above, so he could brace himself against the

hull. Many faces were peering over at him anxiously: strangers;

then another man came sliding down over the rail, and another, to

work on the other harpoons.

Laurence began the grim effort of sawing away at the cable,

strands going one at a time; the rope was cable-laid, three hawsers

of three strands, well-wormed and thick as a man’s wrist and

parceled in canvas, and meanwhile he made a bright target against

the ship’s paintwork for the guns of the frigate. If he were killed, the

embarrassment of his hanging would at least be spared his family.

He was only alive now to be a chain round Temeraire’s neck, until

the Admiralty should decide the dragon pacified enough by age and

habit that Laurence might be dispensed with and his sentence carried

out; and that might be years, long years, mouldering in gaol or

in the bowels of a ship.

It was not a purposeful thought, no guilty intention; it only

crossed his mind involuntarily, while he worked. He had his back to

the ocean and could not see anything of the frigate or the larger battle

beyond: his horizon was the splintered paint of Goliath’s side,

lacquered shine made rough by splinters and salt, and the cold sea

was climbing up her hull and spraying his back. Distant roars of

cannon-fire spoke, but Goliath had let her guns fall silent, saving

her powder and shot for when they should be of some use. The

loudest noises in his ears were the grunts and effort of the men

hanging nearby, sawing at their own harpoon-lines. Then one of

them gave a startled yell and let go his rope, falling away into the

churning ocean; a small darting courier-beast, a Chasseur-Vocifère,

was plunging at the side of the ship with another harpoon.

The beast held it something like a jouster in a medieval tournament,

with the butt rigged awkwardly into a cup attached to its harness,

for support, and two men on its back bracing the rig. The

harpoon thumped dully against the ship’s side, near to where Laurence

hung, and the dragon’s tail slapped a wash of salt water up

into his face, heavy stinging thickness in his nostrils and dripping

down the back of his throat as he choked it out. The dragon lunged

away again even as the Marines fired off a furious volley, trailing

the harpoon on its line behind it: the barb had not bitten deep

enough to penetrate. The hull was pockmarked with the dents of

earlier attempts, a good dozen for each planted harpoon marring

her spit-and-polish paintwork.

Laurence wiped salt from his face against his arm and shouted,

“Keep working, man, damn you,” at the other seaman still hanging

near him. The first rope of his own cable was gone at last, tough fibres

fraying away from the cutlass edge and fanning out like a

broom; he began on the second, rapidly, although the blade was

going dull.

The frigate was still there to harass them, and he could not help

but look around at the roar of cannon so nearby. A ball came

whistling across the water, skipping two, three times along the

wave-tops, like a stone thrown by a boy. It looked as though it came

straight for him, an illusion: the whole ship groaned as the ball

punched in at the bows, and splinters flew like a sudden blizzard

out of the open portholes. They peppered Laurence’s legs, stinging

like a flock of bees, and his stockings were quickly wet with blood.

He clung on to the harpoon arm and kept sawing; the frigate was

still firing, broadside rolling on, and the round-shot hurtled at them

again and again, a sickening deep sway to Goliath’s motion now as

she took the pounding.

He had to hand the cutlass back in and shout for a fresh to get

through the last strand; then at last the cable was cut loose and

swinging away free, and they pulled him back in; he staggered when

he tried to stand, and went to his knees slipping in blood: stockings

laddered and soaked through red; his best breeches, still the same

ones he had worn for the trial, were pierced and spotted. He was

helped to sit against the wall, and turned the cutlass on his own

shirt for bandages to tie up the worst of the gashes; no-one could be

spared to help him to the surgeons. The other harpoons had been

cut; they were moving at last, coming around; and all the crews

were fixed by their guns, savage in the dim red glow penetrating,

teeth bared and mazed with blood from cracked lips and gums,

faces black with sweat and grime, ready to take vengeance.

A loud pattering like rain or hailstones came suddenly down:

small bombs with short fuses dropped by the French dragons,

flashes like lightning visible through the boards of the deck; some

rolled down through the ladderways and burst in the gundeck, hot

flash-powder smoke and the burning glare of pyrotechnics, painful

to the eyes; then they hove around in view of the frigate and the

order came down to fire, fire.

There was nothing for a long moment but the mindless fury of

the ship’s guns going: impossible to think in that roaring din, smoke

and hellish fire in her bowels choking away all reason. Laurence

reached up for the porthole when they had paused, and hauled himself

up to look. The French frigate was reeling away under the

pounding, her foremast down and hulled below the water-line, so

each wave slapping away poured into her.

There was no cheering. Past the retreating frigate, the breadth of

the Channel spread open before them, and all the great ships of the

blockade, entangled and harassed just as they had been. The

Aboukir and the mighty Sultan, seventy-four guns, were near

enough to recognize: cables rising up to three and four dragons,

French heavy-weights and middle-weights industriously tugging

every which way. The ships were firing steadily but uselessly, clouds

of smoke that did not reach the dragons above.

And between them, half-a-dozen French ships-of-the-line, come

out of harbor at last, were stately going by, escort to an enormous

flotilla. A hundred and more, barges and fishing-boats and even

rafts in lateen rig, all of them crammed with soldiers, the wind at

their backs and the tide carrying them towards the shore, tricolors

streaming proudly from their bows towards England.

With the Navy paralyzed, only the dragons of the Corps were

left to stop the advance. But the French warships were firing regularly

into the air above the flotilla: something like pepper, in vaster

quantities than could have been afforded of spice, and burning. Red

spark fragments glowed like fireflies against the black smoke-cloud

which hung over the boats, shielding them from aerial attack. One

of the transport boats was near enough that Laurence saw the men

had their faces covered with wet kerchiefs and rags, or huddled

under oilcloth sheets. The British dragons made desperate attempts

to dive, but recoiled from the clouds, and had instead to fling down

bombs from too great a height: ten splashing into the wide ocean

for every one which came near enough to make a wave against a

ship’s hull. The smaller French dragons harried them, too, flying

back and forth and jeering in shrill voices. There were so many of

them, Laurence had never seen so many: wheeling almost like birds,

clustering and breaking apart, offering no easy target to the British

dragons in their stately formations.

One great Regal Copper might have been Maximus: red and orange

and yellow against the blue sky, at the head of a formation

with Yellow Reapers in two lines to his either wing, but Laurence

did not see Lily. The Regal roared, audible faintly even over the distance,

and bulled his formation through a dozen French lightweights

to come at a great French warship: flames bloomed from

her sails as the bombs at last hit, but when the formation rose away

again, one of the Reapers was streaming crimson from its belly and

another was listing. A handful of British frigates, too, were valiantly

trying to dash past the French ships to come at the transports: with

some little success, but they were under heavy fire, and if they sank

a dozen boats, half the men were pulled aboard others, so close

were the little transports to one another.

“Every man to his gun,” the lieutenant said sharply. Goliath

was turning to go after the transports. She would be passing between

Majestueux and Héros, a broadside of nearly three tons between

them. Laurence felt it when her sails caught the wind

properly again: the ship leaping forward like an eager racehorse