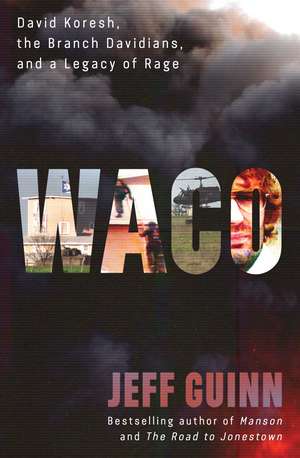

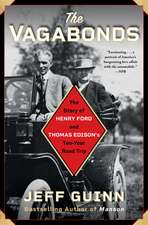

Waco: David Koresh, the Branch Davidians, and A Legacy of Rage

Autor Jeff Guinnen Limba Engleză Hardback – 15 feb 2023

Waco breaks new ground that will change the perception of the dramatic events that happened in Waco, Texas, in 1993. Among other revelations, the book shows how David Koresh directly based his famous End Time prophecies on the writings of a previous “prophet” laying claim to the name Koresh—Cyrus Teed, in Fort Myers, Florida, in the late 1890s.

More than a dozen former AFT agents who participated in the initial February 28, 1993 raid on Mount Carmel speak for the first time on the record about the poor decisions of their raid commanders that led to this deadly confrontation. They also provided Guinn with documents and photographs that have never been published. An FBI agent/analyst who was involved in the fifty-one-day siege offers fresh information about why the FBI agent in charge chose to end the siege with the use of CS gas and about a failed FBI cover-up afterward. There is also documentation of the direct links between the Branch Davidian tragedy and the modern militia movement in America—notorious conspiracist Alex Jones is a part of the Waco story.

Jeff Guinn puts you right alongside the ATF agents as they embarked on the disastrous initial assault, unaware that the Davidians knew they were coming and were armed and prepared to resist—which the agents had been told would not happen. Drawing on new eyewitness accounts, Jeff Guinn again does what he did with his bestselling books about Charles Manson and Jim Jones, shedding new light on a story that everyone thinks they know.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 70.71 lei 3-5 săpt. | +13.10 lei 5-11 zile |

| Simon&Schuster – 22 mai 2024 | 70.71 lei 3-5 săpt. | +13.10 lei 5-11 zile |

| Hardback (2) | 128.79 lei 3-5 săpt. | +24.30 lei 5-11 zile |

| Simon&Schuster – 15 feb 2023 | 128.79 lei 3-5 săpt. | +24.30 lei 5-11 zile |

| Gale, a Cengage Company – 9 aug 2023 | 279.90 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 128.79 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.65€ • 25.64$ • 20.35£

24.65€ • 25.64$ • 20.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 34.29 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982186104

ISBN-10: 1982186100

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8-pg b&w insert

Dimensiuni: 156 x 235 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.59 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1982186100

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8-pg b&w insert

Dimensiuni: 156 x 235 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.59 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Jeff Guinn is the bestselling author of numerous books, including Go Down Together, The Last Gunfight, Manson, The Road to Jonestown, War on the Border, and Waco. He lives in Fort Worth, Texas, and is a member of the Texas Literary Hall of Fame.

Extras

ProloguePROLOGUE ATF, Morning, February 28, 1993

Just before dawn on Sunday, February 28, 1993, an eighty-vehicle caravan departed Fort Hood Army base outside Killeen, Texas, heading northeast toward Waco, sixty-five miles away. Cattle trailers pulled by pickup trucks took the lead and brought up the rear. In between was a hodgepodge of sports cars, station wagons, and nondescript government-issue sedans sporting telltale extended antennas. All had their headlights on—it was that early morning time when darkness and daylight weave together, and a brisk, chilly breeze blew about puffs of ground fog. Rain seemed certain sooner rather than later. The less-than-perfect weather was irritating, but the drivers in the mile-long procession had other things on their minds. They were all agents of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, better known as ATF and tasked with enforcing often unpopular federal laws. For the last two days, they’d been receiving special training at Fort Hood. In another few hours, they were scheduled to participate in the largest and, hopefully, best-publicized raid in agency history, one that might improve perception of their controversial organization.

Since late June 1992, ATF had investigated prophet David Koresh and his followers, collectively known as the Branch Davidians and living in a sprawling, makeshift building (ATF reports described it as a “compound”) called Mount Carmel on seventy-seven hardscrabble acres about eight miles outside Waco. ATF planners believed approximately seventy-five men, women, and children occupied the fire-ant-infested property; it was hard to get an accurate count because they milled in and around their building so incessantly. After eight months, accumulated evidence indicated that the group was illegally altering guns from semi- to fully automatic, with the intent of either selling them or else using the fearsome weapons as part of a plot to bring about the end of the world. This, ATF tactical planners speculated, might involve anything from an assault on outsiders to gory group suicide.

Though specifically what the Branch Davidians believed, and exactly what they intended, wasn’t clear to the ATF, it was still obvious that they at least had illegal guns in their possession, and illegal homemade “improvised explosive devices” (hand grenades), too. This made them lawbreakers, and appropriate targets of agency action. Two days earlier, on Friday, February 26, a U.S. district judge signed off on an ATF search warrant for Mount Carmel; a criminal complaint against, and an arrest warrant for, Vernon Wayne Howell (David Koresh’s given name); and, critically, an order to immediately seal the warrants from public view. ATF organizers feared above all else losing the element of surprise; every possible step to catch the suspects off guard was built into the raid plan.

Traditionally, ATF raids took one of two forms: “surround and call out,” giving suspects a chance to give up peacefully, and “dynamic entry,” bursting into the suspects’ lair before they had time to take up arms and resist. After many meetings and drawn-out discussions, dynamic entry became the plan for Mount Carmel, avoiding any potential for the Branch Davidians fighting back, destroying evidence, or committing mass suicide before arriving agents could stop them. The ATF’s intent was to swoop in, arrest Koresh, find and confiscate critical evidence, and close the raid without a shot fired by either side, with at least some of this efficient, bloodless action captured on film for the benefit of the media and members of Congress. ATF budgetary hearings were scheduled in March.

There were obvious impediments to the plan. The Branch Davidian property was located off a narrow country road, at the end of a long driveway winding up a barren slope with no cover for anyone approaching the front door. The suspects were up at dawn every day, and believed to be handy with their arsenal. But ATF officials based their plan on two factors vouched for by informants, former Branch Davidians who’d turned against Koresh. First, Koresh kept tight control on weapons; all guns were kept in a locked storage room and taken out only on the leader’s personal command. Second, Mount Carmel residents adhered to a rigid daily schedule. Each morning after breakfast there was “the daily,” a gathering for communion (grape juice and crackers rather than wine and wafers) and scripture-based discussion. After that, certainly by 10 a.m., all able-bodied men on the property came outside to continue excavation of a massive pit that surviving Branch Davidians later described as a tornado shelter. The ATF believed it was intended as a bunker to provide cover during firefights.

So, in just a few hours on this damp Sunday morning, the Branch Davidian men would be working outside, their guns would be locked away inside, and seventy-six ATF agents, concealed in two cattle trailers, a common sight on Central Texas country back roads, would rumble up the Mount Carmel driveway, emerge from the trailers on the double, get between the Branch Davidian men and their guns, and gain control of the property. From there, it would be easy. Everything hinged on taking the suspects by surprise. Raid planners were so confident of succeeding that there was not a fully formed Plan B if things didn’t go as anticipated. During their special training at Fort Hood, ATF agent Mike Duncan recalls, someone asked a supervisor, “What happens if things go to shit? There’s no place to take cover.” The response was vague—get out of the trailers, move away from the compound, return any fire. Agent Dave DiBetta remembers, “That sounded like something out of Monty Python and the Holy Grail; our [backup] plan is to get out of the trailers and run away, and then surround the place?” But the agents bought into the basic premise; the Branch Davidians would do as expected, and total surprise would be achieved.

The ATF caravan reached the Bellmead Civic Center around 7:45 a.m. (Six agents arrived several hours earlier, and had already departed to secure the muddy, wooded area behind Mount Carmel and prevent escape in that direction.) This collection of squat public buildings just off Texas State Highway 84 was chosen as the raid staging area for its convenient location—the tiny town of Bellmead was a few miles northeast of Waco and nine miles from Mount Carmel. Despite planners’ fixation on surprising the Branch Davidians, no thought was apparently given to concealing ATF’s presence from Bellmead locals—an ATF official, wearing a jacket emblazoned with the agency’s emblem, and several Bellmead cops stood in the street, directing caravan cars into the parking lot. Bill Buford, leader of an ATF Special Response Team (SRT) from the agency’s New Orleans division, was appalled when he went inside and found “some sweet ladies, ten or twelve of them,” serving coffee and doughnuts. The refreshments were welcome, but, at least to Buford, the civilians weren’t: “It was obvious we were about to do something. [The women] could have told people about it.”

The agents had about ninety minutes to go over raid plans with team leaders, change into combat gear, and prepare to board the cattle trailers for what would be another fifteen- or twenty-minute ride to Mount Carmel. Stacked in three abreast, thirty-seven agents would ride in Trailer #1 and thirty-nine in Trailer #2. Two ladders would also be crammed into the second trailer; some of the agents were expected to scale their way up to a roof just beneath an upper floor on a side of the compound where Koresh supposedly kept the guns locked away in a room.

The atmosphere as agents sipped coffee and chatted was energized rather than nervous. Most were either veterans of the U.S. military with considerable combat experience, or else had previously worked as police officers or members of the Border Patrol. There were elements about this operation that were unique, that made it, in the opinion of agent Rory Heisch, “a BFD, Big Fucking Deal.” For the first time in agency history, agents from multiple divisions—Houston, Dallas, and New Orleans—would combine in a joint operation. Typical ATF raids might involve up to twenty participants: an entry team, a perimeter team, and perhaps one or two members of the local sheriff’s department. But those raids usually took place at houses or apartments no larger than a few thousand square feet.

The Mount Carmel facility, so far as ATF planners could tell, sprawled approximately 43,000 square feet, and there were questions about the actual floor plan inside. Because the Branch Davidians had built the place haphazardly and without outside contractors, there was no blueprint on file for the ATF to study. During training at Fort Hood, masking tape and rope were used to indicate approximate room locations. Beyond the certainty about the group’s daily schedule and that all guns were locked away in an upstairs room, most of the rest of the raid plan for taking control of Mount Carmel’s interior was based on guesswork. One hundred and thirty-seven ATF agents, including support personnel, were on hand that morning to participate in the raid. It was impossible to be certain if that was the right number, too many, or too few.

About half of the seventy-six agents assigned to the dynamic entry were members of ATF Special Response Teams, the agency’s elite tactical units. SRTs were still relatively new; especially with the proliferation of hostage situations occurring across all of law enforcement, ATF agents had badgered their superiors for additional training equivalent to that undertaken by police department SWAT teams. Selection for SRT training didn’t mean more money—it was voluntary—but it brought considerable status within the agency. With that status came risk: SRTs led the way into every major, potentially volatile encounter. Even so, agents’ training and ability to remain cool under extreme pressure was reflected in an astonishing statistic: in the three years previous, ATF’s crack emergency teams executed 603 warrants and gunfire occurred only twice, with a total of three fatalities, all suspects. No one at ATF ever set out intending to injure, let alone kill, anyone.

This was apparent as agents prepared for the Mount Carmel raid. They armed themselves to gain and retain control rather than engage in a firefight. A half dozen agents carried AR-15 semiautomatic rifles, but most of the rest had lower-powered semiautomatic MP5s out of concern that Mount Carmel’s walls, floors, and ceilings were apparently constructed of flimsy materials. If any shooting did occur, agents didn’t want their bullets plowing into adjacent rooms where women and children might be sheltering. A few agents had shotguns. Almost everyone had a holstered handgun, and, particularly among the most veteran agents, a backup handgun. Agent Robert Champion was assigned to lug a fire extinguisher. The Branch Davidians had lots of dogs, some known to be aggressive. If any dogs attacked the raiders, Champion was to spray them with the extinguisher, in hopes that this would subdue the animals without making it necessary to shoot them.

Everyone donned protective vests, though the protective plates in them would not necessarily stop bullets fired from the high-powered guns that ATF believed the Branch Davidians had. Some of the agents who would lead the way through Mount Carmel’s front door even removed these plates from their vests, anticipating that, since the Branch Davidian men wouldn’t have access to guns, there might be some hand-to-hand fighting instead. A front vest plate alone weighed twelve pounds. Removing the plates gave these agents more mobility. Agents’ headgear ranged from a variety of helmets to woolen caps; ATF’s limited budget did not allow for providing much equipment beyond guns, ammunition, and vests. Penny-pinching was a fact of ATF life. Agents had to scrounge their helmets from military surplus outlets (frequently substituted wool caps were cheaper), and most bought their own combat boots, too. But despite forced frugality limiting their gear, the agents knew that, when they swarmed Mount Carmel, they’d still be an intimidating sight. Even the most apparently hard-bitten suspects usually surrendered abjectly when faced with the unexpected appearance of trained, combat-ready professionals. Agent Blake Boteler recalls, “We didn’t think much about them [the Branch Davidians] fighting to the death. A lot of people claim they’ll do that. If ten do, then when we kick down that door, four wet their pants and the other six may curl up like a ball on the floor. Sometimes, there’s one ready to fight. The element of surprise helps. It gets people on their heels. They intend to fight, but self-preservation takes over and overrules whatever doctrine they have in their heads.”

Far from actually fighting, ATF hoped to create a family-friendly atmosphere. Several females were among the seventy-six agents about to participate in the raid. They would enter Mount Carmel after the SRTs secured the building, then separate the Branch Davidian women and children from the men, gently escorting them to another area, where they’d soothe the kids by offering them candy. It was understood that Branch Davidian offspring rarely enjoyed such treats. When things were more settled, one or two agents were assigned to drive to a nearby McDonald’s and bring back sacks of Happy Meals for the youngsters. ATF support staff planned to bring tents to keep the Branch Davidian women and children out of the cold, wet weather, and to set up Port-o-Lets so that they could relieve themselves in privacy, undoubtedly a welcome alternative to the ubiquitous buckets that comprised plumbing-free Mount Carmel’s facilities. At the Bellmead Civic Center, all the women agents stuffed their pockets with candy, and so did some of the male agents. They hoped that the Mount Carmel kids, and perhaps their mothers, too, would feel less panicked thanks to all this bounty.

Even the final go-word signaling agents to exit the trailers and rush the compound was selected to be as nonaggressive as possible. The raid itself had the code name “Trojan Horse.” ATF’s traditional call to action was “Execute,” but the term seemed risky: if that portion of the raid was recorded for public replay, irresponsible members of the media and Congress might cite “Execute” as an indicator of lethal intention. So, for the Mount Carmel raid, the go-word would be “Showtime!”

The raid leaders were Phil Chojnacki and Chuck Sarabyn, the special agent in charge (SAC) and assistant special agent in charge (ASAC) from ATF’s Houston office. They were assigned these roles because Waco was part of their larger Houston region. There was some concern, especially among the more veteran agents, about Chojnacki and Sarabyn as raid leaders. Neither was considered to have much field experience. On this day, Chojnacki was scheduled to observe the raid from above in one of three helicopters provided to the ATF as support by the Texas National Guard, and Sarabyn planned to ride into Mount Carmel in Cattle Trailer #1. For the moment, both were out at ATF’s field headquarters on the campus of Texas State Technical College (TSTC), a site several miles away from the Bellmead Civic Center and Mount Carmel, but handy for an adjacent landing strip that could accommodate the National Guard helicopters.

In early January, ATF had also established what the agency termed an “undercover house” in a rental property directly across the road from Mount Carmel, and staffed it with eight male agents pretending to be TSTC students. One of these agents managed to visit Koresh at Mount Carmel several times. This morning, he was supposed to go into the compound one final time, to ensure that the Branch Davidian day was on its anticipated schedule, and that the suspects still had no inkling of ATF’s imminent arrival. Once the agent confirmed these facts to Sarabyn at the TSTC command post, the second-in-command would come to the Bellmead Civic Center and the raid would commence.

A point of unexpected concern was the first in a series of investigative articles about Koresh that was published on Saturday, February 27, by the Waco Tribune-Herald. Titled “The Sinful Messiah,” the initial stories indicated that Koresh maintained a harem of Mount Carmel women, including underage girls, and that Branch Davidian children were so savagely disciplined that Texas Child Protective Services had investigated, though not enough evidence had been found for CPS staff to bring a case. Learning of the series in advance, ATF officials worried that its publication might goad the Branch Davidians into high alert and thwart the agency’s plans for a surprise raid. At Fort Hood, the ATF agents were informed that the newspaper’s editors had refused the agency’s request to briefly postpone the series. Originally, ATF scheduled its raid for Monday, March 1. After being rebuffed by the Tribune-Herald, agency officials moved the date up one day to Sunday, February 28—Fort Hood training was cut from three full days to two. About the same time on Sunday morning that the ATF convoy left Fort Hood, Koresh and the Branch Davidians were reading a second installment of accusatory stories. The undercover ATF agent’s morning visit to Mount Carmel was especially critical; he was to observe whether the newspaper’s series was in any way disrupting the Branch Davidians’ usual daily schedule.

Just after 9 a.m., operation second-in-command Chuck Sarabyn rushed into the room where agents continued making their preparations for the Mount Carmel raid. He was clearly upset, shouting, “Get geared up, we’ve got to go now,” and several agents remember Sarabyn adding, “They know we’re coming.” To SRT team leaders Bill Buford and Jerry Petrilli, yelling out this news to the room at large was a breach of protocol. As raid tactical leader, Sarabyn should have first quietly summoned the more experienced team leaders to his side and elicited their advice before making and announcing the decision to carry on, even though the critical element of surprise was lost. They tried to calm Sarabyn and get more details. Both Petrilli and Buford recall that he kept repeating, “We’ve got to go right now.”

Sarabyn did share more information: the undercover agent in the Branch Davidian building had said Koresh got a phone call and immediately afterward told his followers that the ATF and National Guard were coming. But Koresh didn’t send the Branch Davidian men to the gun room to arm themselves. Instead, according to Sarabyn, the undercover agent reported that Koresh was sitting and holding a Bible. There was no sign of any weapons. There was still time to get to Mount Carmel before the suspects could prepare themselves to resist, if they planned to at all. All seventy-six participating agents scrambled to complete gearing up. SRT tactical medics used Magic Markers to note blood types on the agents’ necks. This was a new precautionary measure adopted during training at Fort Hood.

Most of the agents in the room felt some degree of skepticism. The plan had been to call off the raid if surprise was lost. The Branch Davidians held the high ground and had higher-powered weapons than the federal agents. If they were ready to fight, then the arriving ATF would face a head-on barrage with limited access to even minimal cover. But a chain-of-command mentality was imbued in them: when orders were given, they must be followed. If, as Sarabyn indicated, Koresh really was reading the Bible instead of rallying his followers to fight, maybe the mission could still be successfully completed. A few agents, mostly younger ones craving the opportunity to be in on some action, remained unabashedly gung ho. There was a general rush to the cattle trailers. Order of trailer entry had been rehearsed to the point of tedium at Fort Hood. Now, everyone hustled into proper position. Light rain began falling. It was still quite chilly. The back gates of the trailers snapped shut, and the pickup trucks pulling the trailers lurched out of the civic center parking lot.

“We were sardined in, bumping up against the next guy,” Mike Russell remembers. “Those trailers didn’t have springs.” The narrow county roads between Bellmead Civic Center and Mount Carmel were roughly paved, “and we were all bouncing around, trying to find something to hang on to, maybe the iron bar overhead or bracing against the side.” Plywood slabs were tacked to the sides of the trailers, and plastic tarp stretched across the roofs, to prevent anyone from seeing in. But it also prevented the agents seeing much on the outside—the only interior light on this drab morning came between sections of plywood, or else seeped through the thin tarp taped overhead. But they could see each other, and most appeared worried. Champion says, “It was pucker time.” They all had radios, and listened for any additional information. But there was nothing until they were almost to Mount Carmel, when word crackled through: “There’s nobody outside.” That chilled everyone. Boteler thought, They’re either inside destroying evidence, or else they’re arming up and we’ll run into a buzz saw.

In Trailer #1, SRT team leader Petrilli wished he could tell Sarabyn one more time “how bad I think this is,” but Petrilli was wedged tight in the middle of the trailer itself, while Sarabyn rode with the driver in the cab of the pickup truck. So Petrilli, bowing to the inevitable, passed the word to his squad: “It’s showtime; goggles down and fingers off the triggers.” In Trailer #2, the driver shouted back to his passengers, “When I stop, you go.”

Russell, struggling to keep his balance like everyone else in Trailer #2 as it made a wide right turn onto Mount Carmel’s driveway, had a final, hopeful thought: Well, maybe Koresh heard we were investigating, and would probably be coming after him. But maybe he doesn’t know that we’re coming right now.

He did.

Just before dawn on Sunday, February 28, 1993, an eighty-vehicle caravan departed Fort Hood Army base outside Killeen, Texas, heading northeast toward Waco, sixty-five miles away. Cattle trailers pulled by pickup trucks took the lead and brought up the rear. In between was a hodgepodge of sports cars, station wagons, and nondescript government-issue sedans sporting telltale extended antennas. All had their headlights on—it was that early morning time when darkness and daylight weave together, and a brisk, chilly breeze blew about puffs of ground fog. Rain seemed certain sooner rather than later. The less-than-perfect weather was irritating, but the drivers in the mile-long procession had other things on their minds. They were all agents of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, better known as ATF and tasked with enforcing often unpopular federal laws. For the last two days, they’d been receiving special training at Fort Hood. In another few hours, they were scheduled to participate in the largest and, hopefully, best-publicized raid in agency history, one that might improve perception of their controversial organization.

Since late June 1992, ATF had investigated prophet David Koresh and his followers, collectively known as the Branch Davidians and living in a sprawling, makeshift building (ATF reports described it as a “compound”) called Mount Carmel on seventy-seven hardscrabble acres about eight miles outside Waco. ATF planners believed approximately seventy-five men, women, and children occupied the fire-ant-infested property; it was hard to get an accurate count because they milled in and around their building so incessantly. After eight months, accumulated evidence indicated that the group was illegally altering guns from semi- to fully automatic, with the intent of either selling them or else using the fearsome weapons as part of a plot to bring about the end of the world. This, ATF tactical planners speculated, might involve anything from an assault on outsiders to gory group suicide.

Though specifically what the Branch Davidians believed, and exactly what they intended, wasn’t clear to the ATF, it was still obvious that they at least had illegal guns in their possession, and illegal homemade “improvised explosive devices” (hand grenades), too. This made them lawbreakers, and appropriate targets of agency action. Two days earlier, on Friday, February 26, a U.S. district judge signed off on an ATF search warrant for Mount Carmel; a criminal complaint against, and an arrest warrant for, Vernon Wayne Howell (David Koresh’s given name); and, critically, an order to immediately seal the warrants from public view. ATF organizers feared above all else losing the element of surprise; every possible step to catch the suspects off guard was built into the raid plan.

Traditionally, ATF raids took one of two forms: “surround and call out,” giving suspects a chance to give up peacefully, and “dynamic entry,” bursting into the suspects’ lair before they had time to take up arms and resist. After many meetings and drawn-out discussions, dynamic entry became the plan for Mount Carmel, avoiding any potential for the Branch Davidians fighting back, destroying evidence, or committing mass suicide before arriving agents could stop them. The ATF’s intent was to swoop in, arrest Koresh, find and confiscate critical evidence, and close the raid without a shot fired by either side, with at least some of this efficient, bloodless action captured on film for the benefit of the media and members of Congress. ATF budgetary hearings were scheduled in March.

There were obvious impediments to the plan. The Branch Davidian property was located off a narrow country road, at the end of a long driveway winding up a barren slope with no cover for anyone approaching the front door. The suspects were up at dawn every day, and believed to be handy with their arsenal. But ATF officials based their plan on two factors vouched for by informants, former Branch Davidians who’d turned against Koresh. First, Koresh kept tight control on weapons; all guns were kept in a locked storage room and taken out only on the leader’s personal command. Second, Mount Carmel residents adhered to a rigid daily schedule. Each morning after breakfast there was “the daily,” a gathering for communion (grape juice and crackers rather than wine and wafers) and scripture-based discussion. After that, certainly by 10 a.m., all able-bodied men on the property came outside to continue excavation of a massive pit that surviving Branch Davidians later described as a tornado shelter. The ATF believed it was intended as a bunker to provide cover during firefights.

So, in just a few hours on this damp Sunday morning, the Branch Davidian men would be working outside, their guns would be locked away inside, and seventy-six ATF agents, concealed in two cattle trailers, a common sight on Central Texas country back roads, would rumble up the Mount Carmel driveway, emerge from the trailers on the double, get between the Branch Davidian men and their guns, and gain control of the property. From there, it would be easy. Everything hinged on taking the suspects by surprise. Raid planners were so confident of succeeding that there was not a fully formed Plan B if things didn’t go as anticipated. During their special training at Fort Hood, ATF agent Mike Duncan recalls, someone asked a supervisor, “What happens if things go to shit? There’s no place to take cover.” The response was vague—get out of the trailers, move away from the compound, return any fire. Agent Dave DiBetta remembers, “That sounded like something out of Monty Python and the Holy Grail; our [backup] plan is to get out of the trailers and run away, and then surround the place?” But the agents bought into the basic premise; the Branch Davidians would do as expected, and total surprise would be achieved.

The ATF caravan reached the Bellmead Civic Center around 7:45 a.m. (Six agents arrived several hours earlier, and had already departed to secure the muddy, wooded area behind Mount Carmel and prevent escape in that direction.) This collection of squat public buildings just off Texas State Highway 84 was chosen as the raid staging area for its convenient location—the tiny town of Bellmead was a few miles northeast of Waco and nine miles from Mount Carmel. Despite planners’ fixation on surprising the Branch Davidians, no thought was apparently given to concealing ATF’s presence from Bellmead locals—an ATF official, wearing a jacket emblazoned with the agency’s emblem, and several Bellmead cops stood in the street, directing caravan cars into the parking lot. Bill Buford, leader of an ATF Special Response Team (SRT) from the agency’s New Orleans division, was appalled when he went inside and found “some sweet ladies, ten or twelve of them,” serving coffee and doughnuts. The refreshments were welcome, but, at least to Buford, the civilians weren’t: “It was obvious we were about to do something. [The women] could have told people about it.”

The agents had about ninety minutes to go over raid plans with team leaders, change into combat gear, and prepare to board the cattle trailers for what would be another fifteen- or twenty-minute ride to Mount Carmel. Stacked in three abreast, thirty-seven agents would ride in Trailer #1 and thirty-nine in Trailer #2. Two ladders would also be crammed into the second trailer; some of the agents were expected to scale their way up to a roof just beneath an upper floor on a side of the compound where Koresh supposedly kept the guns locked away in a room.

The atmosphere as agents sipped coffee and chatted was energized rather than nervous. Most were either veterans of the U.S. military with considerable combat experience, or else had previously worked as police officers or members of the Border Patrol. There were elements about this operation that were unique, that made it, in the opinion of agent Rory Heisch, “a BFD, Big Fucking Deal.” For the first time in agency history, agents from multiple divisions—Houston, Dallas, and New Orleans—would combine in a joint operation. Typical ATF raids might involve up to twenty participants: an entry team, a perimeter team, and perhaps one or two members of the local sheriff’s department. But those raids usually took place at houses or apartments no larger than a few thousand square feet.

The Mount Carmel facility, so far as ATF planners could tell, sprawled approximately 43,000 square feet, and there were questions about the actual floor plan inside. Because the Branch Davidians had built the place haphazardly and without outside contractors, there was no blueprint on file for the ATF to study. During training at Fort Hood, masking tape and rope were used to indicate approximate room locations. Beyond the certainty about the group’s daily schedule and that all guns were locked away in an upstairs room, most of the rest of the raid plan for taking control of Mount Carmel’s interior was based on guesswork. One hundred and thirty-seven ATF agents, including support personnel, were on hand that morning to participate in the raid. It was impossible to be certain if that was the right number, too many, or too few.

About half of the seventy-six agents assigned to the dynamic entry were members of ATF Special Response Teams, the agency’s elite tactical units. SRTs were still relatively new; especially with the proliferation of hostage situations occurring across all of law enforcement, ATF agents had badgered their superiors for additional training equivalent to that undertaken by police department SWAT teams. Selection for SRT training didn’t mean more money—it was voluntary—but it brought considerable status within the agency. With that status came risk: SRTs led the way into every major, potentially volatile encounter. Even so, agents’ training and ability to remain cool under extreme pressure was reflected in an astonishing statistic: in the three years previous, ATF’s crack emergency teams executed 603 warrants and gunfire occurred only twice, with a total of three fatalities, all suspects. No one at ATF ever set out intending to injure, let alone kill, anyone.

This was apparent as agents prepared for the Mount Carmel raid. They armed themselves to gain and retain control rather than engage in a firefight. A half dozen agents carried AR-15 semiautomatic rifles, but most of the rest had lower-powered semiautomatic MP5s out of concern that Mount Carmel’s walls, floors, and ceilings were apparently constructed of flimsy materials. If any shooting did occur, agents didn’t want their bullets plowing into adjacent rooms where women and children might be sheltering. A few agents had shotguns. Almost everyone had a holstered handgun, and, particularly among the most veteran agents, a backup handgun. Agent Robert Champion was assigned to lug a fire extinguisher. The Branch Davidians had lots of dogs, some known to be aggressive. If any dogs attacked the raiders, Champion was to spray them with the extinguisher, in hopes that this would subdue the animals without making it necessary to shoot them.

Everyone donned protective vests, though the protective plates in them would not necessarily stop bullets fired from the high-powered guns that ATF believed the Branch Davidians had. Some of the agents who would lead the way through Mount Carmel’s front door even removed these plates from their vests, anticipating that, since the Branch Davidian men wouldn’t have access to guns, there might be some hand-to-hand fighting instead. A front vest plate alone weighed twelve pounds. Removing the plates gave these agents more mobility. Agents’ headgear ranged from a variety of helmets to woolen caps; ATF’s limited budget did not allow for providing much equipment beyond guns, ammunition, and vests. Penny-pinching was a fact of ATF life. Agents had to scrounge their helmets from military surplus outlets (frequently substituted wool caps were cheaper), and most bought their own combat boots, too. But despite forced frugality limiting their gear, the agents knew that, when they swarmed Mount Carmel, they’d still be an intimidating sight. Even the most apparently hard-bitten suspects usually surrendered abjectly when faced with the unexpected appearance of trained, combat-ready professionals. Agent Blake Boteler recalls, “We didn’t think much about them [the Branch Davidians] fighting to the death. A lot of people claim they’ll do that. If ten do, then when we kick down that door, four wet their pants and the other six may curl up like a ball on the floor. Sometimes, there’s one ready to fight. The element of surprise helps. It gets people on their heels. They intend to fight, but self-preservation takes over and overrules whatever doctrine they have in their heads.”

Far from actually fighting, ATF hoped to create a family-friendly atmosphere. Several females were among the seventy-six agents about to participate in the raid. They would enter Mount Carmel after the SRTs secured the building, then separate the Branch Davidian women and children from the men, gently escorting them to another area, where they’d soothe the kids by offering them candy. It was understood that Branch Davidian offspring rarely enjoyed such treats. When things were more settled, one or two agents were assigned to drive to a nearby McDonald’s and bring back sacks of Happy Meals for the youngsters. ATF support staff planned to bring tents to keep the Branch Davidian women and children out of the cold, wet weather, and to set up Port-o-Lets so that they could relieve themselves in privacy, undoubtedly a welcome alternative to the ubiquitous buckets that comprised plumbing-free Mount Carmel’s facilities. At the Bellmead Civic Center, all the women agents stuffed their pockets with candy, and so did some of the male agents. They hoped that the Mount Carmel kids, and perhaps their mothers, too, would feel less panicked thanks to all this bounty.

Even the final go-word signaling agents to exit the trailers and rush the compound was selected to be as nonaggressive as possible. The raid itself had the code name “Trojan Horse.” ATF’s traditional call to action was “Execute,” but the term seemed risky: if that portion of the raid was recorded for public replay, irresponsible members of the media and Congress might cite “Execute” as an indicator of lethal intention. So, for the Mount Carmel raid, the go-word would be “Showtime!”

The raid leaders were Phil Chojnacki and Chuck Sarabyn, the special agent in charge (SAC) and assistant special agent in charge (ASAC) from ATF’s Houston office. They were assigned these roles because Waco was part of their larger Houston region. There was some concern, especially among the more veteran agents, about Chojnacki and Sarabyn as raid leaders. Neither was considered to have much field experience. On this day, Chojnacki was scheduled to observe the raid from above in one of three helicopters provided to the ATF as support by the Texas National Guard, and Sarabyn planned to ride into Mount Carmel in Cattle Trailer #1. For the moment, both were out at ATF’s field headquarters on the campus of Texas State Technical College (TSTC), a site several miles away from the Bellmead Civic Center and Mount Carmel, but handy for an adjacent landing strip that could accommodate the National Guard helicopters.

In early January, ATF had also established what the agency termed an “undercover house” in a rental property directly across the road from Mount Carmel, and staffed it with eight male agents pretending to be TSTC students. One of these agents managed to visit Koresh at Mount Carmel several times. This morning, he was supposed to go into the compound one final time, to ensure that the Branch Davidian day was on its anticipated schedule, and that the suspects still had no inkling of ATF’s imminent arrival. Once the agent confirmed these facts to Sarabyn at the TSTC command post, the second-in-command would come to the Bellmead Civic Center and the raid would commence.

A point of unexpected concern was the first in a series of investigative articles about Koresh that was published on Saturday, February 27, by the Waco Tribune-Herald. Titled “The Sinful Messiah,” the initial stories indicated that Koresh maintained a harem of Mount Carmel women, including underage girls, and that Branch Davidian children were so savagely disciplined that Texas Child Protective Services had investigated, though not enough evidence had been found for CPS staff to bring a case. Learning of the series in advance, ATF officials worried that its publication might goad the Branch Davidians into high alert and thwart the agency’s plans for a surprise raid. At Fort Hood, the ATF agents were informed that the newspaper’s editors had refused the agency’s request to briefly postpone the series. Originally, ATF scheduled its raid for Monday, March 1. After being rebuffed by the Tribune-Herald, agency officials moved the date up one day to Sunday, February 28—Fort Hood training was cut from three full days to two. About the same time on Sunday morning that the ATF convoy left Fort Hood, Koresh and the Branch Davidians were reading a second installment of accusatory stories. The undercover ATF agent’s morning visit to Mount Carmel was especially critical; he was to observe whether the newspaper’s series was in any way disrupting the Branch Davidians’ usual daily schedule.

Just after 9 a.m., operation second-in-command Chuck Sarabyn rushed into the room where agents continued making their preparations for the Mount Carmel raid. He was clearly upset, shouting, “Get geared up, we’ve got to go now,” and several agents remember Sarabyn adding, “They know we’re coming.” To SRT team leaders Bill Buford and Jerry Petrilli, yelling out this news to the room at large was a breach of protocol. As raid tactical leader, Sarabyn should have first quietly summoned the more experienced team leaders to his side and elicited their advice before making and announcing the decision to carry on, even though the critical element of surprise was lost. They tried to calm Sarabyn and get more details. Both Petrilli and Buford recall that he kept repeating, “We’ve got to go right now.”

Sarabyn did share more information: the undercover agent in the Branch Davidian building had said Koresh got a phone call and immediately afterward told his followers that the ATF and National Guard were coming. But Koresh didn’t send the Branch Davidian men to the gun room to arm themselves. Instead, according to Sarabyn, the undercover agent reported that Koresh was sitting and holding a Bible. There was no sign of any weapons. There was still time to get to Mount Carmel before the suspects could prepare themselves to resist, if they planned to at all. All seventy-six participating agents scrambled to complete gearing up. SRT tactical medics used Magic Markers to note blood types on the agents’ necks. This was a new precautionary measure adopted during training at Fort Hood.

Most of the agents in the room felt some degree of skepticism. The plan had been to call off the raid if surprise was lost. The Branch Davidians held the high ground and had higher-powered weapons than the federal agents. If they were ready to fight, then the arriving ATF would face a head-on barrage with limited access to even minimal cover. But a chain-of-command mentality was imbued in them: when orders were given, they must be followed. If, as Sarabyn indicated, Koresh really was reading the Bible instead of rallying his followers to fight, maybe the mission could still be successfully completed. A few agents, mostly younger ones craving the opportunity to be in on some action, remained unabashedly gung ho. There was a general rush to the cattle trailers. Order of trailer entry had been rehearsed to the point of tedium at Fort Hood. Now, everyone hustled into proper position. Light rain began falling. It was still quite chilly. The back gates of the trailers snapped shut, and the pickup trucks pulling the trailers lurched out of the civic center parking lot.

“We were sardined in, bumping up against the next guy,” Mike Russell remembers. “Those trailers didn’t have springs.” The narrow county roads between Bellmead Civic Center and Mount Carmel were roughly paved, “and we were all bouncing around, trying to find something to hang on to, maybe the iron bar overhead or bracing against the side.” Plywood slabs were tacked to the sides of the trailers, and plastic tarp stretched across the roofs, to prevent anyone from seeing in. But it also prevented the agents seeing much on the outside—the only interior light on this drab morning came between sections of plywood, or else seeped through the thin tarp taped overhead. But they could see each other, and most appeared worried. Champion says, “It was pucker time.” They all had radios, and listened for any additional information. But there was nothing until they were almost to Mount Carmel, when word crackled through: “There’s nobody outside.” That chilled everyone. Boteler thought, They’re either inside destroying evidence, or else they’re arming up and we’ll run into a buzz saw.

In Trailer #1, SRT team leader Petrilli wished he could tell Sarabyn one more time “how bad I think this is,” but Petrilli was wedged tight in the middle of the trailer itself, while Sarabyn rode with the driver in the cab of the pickup truck. So Petrilli, bowing to the inevitable, passed the word to his squad: “It’s showtime; goggles down and fingers off the triggers.” In Trailer #2, the driver shouted back to his passengers, “When I stop, you go.”

Russell, struggling to keep his balance like everyone else in Trailer #2 as it made a wide right turn onto Mount Carmel’s driveway, had a final, hopeful thought: Well, maybe Koresh heard we were investigating, and would probably be coming after him. But maybe he doesn’t know that we’re coming right now.

He did.

Recenzii

"Gripping. . . . [Guinn] tells stories we thought we knew and makes us realize we really didn’t. He takes devils of the popular imagination and carefully explains that they’re actually human — a fact that makes them even more terrifying."

“Impressively researched and written with storytelling verve.”

"Thoroughly researched, the many lingering debates explored with the most rigor. [Guinn] He begins with what may be the best account of the ATF raid on Mount Carmel yet written, stocked with new details from interviews with veteran agents and written with clarity and drama."

"Guinn, whose reporting draws heavily on interviews with ATF agents present at Waco, is sympathetic to the agency’s rank-and-file. . . . But overall, [Waco] sketch[es] a portrait of an operation mishandled at almost every level of government."

“Riveting. . . . As the author did in previous reports on Charles Manson and Jonestown, Guinn dives deeply into his subject to present a vivid combination of well-researched facts, personal testimonials, and controversial perspectives. A convincing and chilling coda to this investigation is the correlations Guinn draws among the Davidian compound raid, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, and the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection.”

“Guinn focuses on the standoff and the myriad bad decisions by the ATF and the FBI, capably tracing a throughline to the increase in anti-government hate groups. . . . Extremely well done and thought-provoking.”

"[A] comprehensive and judicious account. . . . Scrupulous and frequently enthralling, this is a sobering account of a tragedy woven into the fabric of modern America."

“Impressively researched and written with storytelling verve.”

"Thoroughly researched, the many lingering debates explored with the most rigor. [Guinn] He begins with what may be the best account of the ATF raid on Mount Carmel yet written, stocked with new details from interviews with veteran agents and written with clarity and drama."

"Guinn, whose reporting draws heavily on interviews with ATF agents present at Waco, is sympathetic to the agency’s rank-and-file. . . . But overall, [Waco] sketch[es] a portrait of an operation mishandled at almost every level of government."

“Riveting. . . . As the author did in previous reports on Charles Manson and Jonestown, Guinn dives deeply into his subject to present a vivid combination of well-researched facts, personal testimonials, and controversial perspectives. A convincing and chilling coda to this investigation is the correlations Guinn draws among the Davidian compound raid, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, and the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection.”

“Guinn focuses on the standoff and the myriad bad decisions by the ATF and the FBI, capably tracing a throughline to the increase in anti-government hate groups. . . . Extremely well done and thought-provoking.”

"[A] comprehensive and judicious account. . . . Scrupulous and frequently enthralling, this is a sobering account of a tragedy woven into the fabric of modern America."

Descriere

The definitive account of the disastrous siege at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, featuring never-before-seen documents, photographs, and interviews, from former investigative reporter and bestselling author Jeff Guinn.