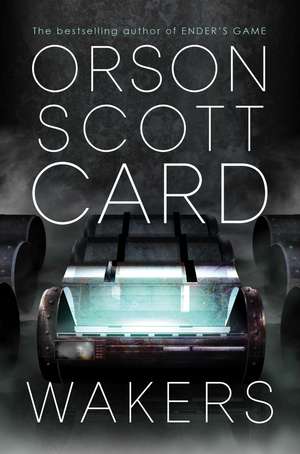

Wakers: The Side Step Trilogy, cartea 1

Autor Orson Scott Carden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 mar 2023 – vârsta de la 14 ani

Laz is a side-stepper: a teen with the incredible power to jump his consciousness to alternate versions of himself in parallel worlds. All his life, there was no mistake that a little side-stepping couldn’t fix.

Until Laz wakes up one day in a cloning facility on a seemingly abandoned Earth.

Laz finds himself surrounded by hundreds of other clones, all dead, and quickly realizes that he too must be a clone of his original self. Laz has no idea what happened to the world he remembers as vibrant and bustling only yesterday, and he struggles to survive in the barren wasteland he’s now trapped in. But the question that haunts him isn’t why was he created, but instead, who woke him up…and why?

There’s only a single bright spot in Laz’s new life: one other clone appears to still be alive, although she remains asleep. Deep down, Laz believes that this girl holds the key to the mysteries plaguing him, but if he wakes her up, she’ll be trapped in this hellscape with him.

This is one problem that Laz can’t just side-step his way out of.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 47.99 lei 25-37 zile | +23.07 lei 5-11 zile |

| Margaret K. McElderry Books – 30 mar 2023 | 47.99 lei 25-37 zile | +23.07 lei 5-11 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 116.47 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Margaret K. McElderry Books – 30 mar 2022 | 116.47 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 47.99 lei

Preț vechi: 58.39 lei

-18% Nou

Puncte Express: 72

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.18€ • 9.55$ • 7.58£

9.18€ • 9.55$ • 7.58£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-09 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 33.06 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781481496209

ISBN-10: 1481496204

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: f-c cvr--no spfx: matte film

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Colecția Margaret K. McElderry Books

Seria The Side Step Trilogy

ISBN-10: 1481496204

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: f-c cvr--no spfx: matte film

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Colecția Margaret K. McElderry Books

Seria The Side Step Trilogy

Notă biografică

Orson Scott Card is the author of numerous bestselling novels and the first writer to receive both the Hugo and Nebula awards two years in a row; first for Ender’s Game and then for the sequel, Speaker for the Dead. He lives with his wife in North Carolina.

Extras

Chapter 11

BECAUSE HE WAS a teenager, and teenagers take pleasure in exploring wacky ideas, Laz Hayerian had wondered since the sixth grade whether we are the same person when we wake up that we were when we went to sleep. Specifically, he wondered if he was the same person, because sometimes his dreams persisted in memory as if they had been real events. Did dream memories change him the way real memories did?

This always led to the deeper question: Since Laz had memories that came, not from dreams, but from timestreams he had stepped out of, did his intertwined memories of other realities make him less sane? Or more experienced? Or both?

Since, as far as he knew, no one else in the world had the ability to side step from one timestream to another, there was no one he could ask, and no philosopher who had written about it.

As he woke up this morning—morning?—he felt very strange, and it wasn’t the residual effect of some dream. He didn’t even remember dreaming. It was his own past that felt like a disjointed dream, as if sometime in the night his whole life played out in his mind, but completely out of order, an incoherent scattering of scenes, facts, feelings, people, places.

When he opened his eyes, he was in nearly complete darkness. Even on mornings at Dad’s place, there was always plenty of light that seeped around the curtains.

All he could see was a tiny amount of green light coming from a few inches to his left.

He was lying on a plastic mattress that felt no more cushioned than the pad in the bottom of a portable crib. Yet he didn’t feel any aches or sore spots, and when he flexed muscles up and down his body, nothing caused him pain.

So Laz did what he had always done since his earliest memories of childhood. He searched for the alternate paths through time that were always close enough for him to take hold and shift, changing the story of events in bold or barely perceptible ways. It didn’t matter which, as long as it got him into a place where things made more sense.

For the first time in his life he could not find any of the alternate timestreams.

No, no, he was finding them, yes, thousands of them—as always. Only none of them went back even a moment earlier than the moment he woke up just now. And none of them showed him doing anything different, so there was no point in side stepping from one to another.

He was afraid. He had never reached out and found that all his pasts and all his futures were identical. It meant he had no choices. Whatever was going on right now, he was like other people—he was trapped.

He didn’t like feeling trapped.

Why was he feeling trapped? He extended his hands away from his sides and they bumped into solid walls. He was in an actual container.

The green light came from some LED letters and numbers on a panel at his left side, inside the box, but he didn’t know what any of them meant. Someone else would explain them to him. If he was in some kind of—what? A medical treatment chamber? An anti-infection box while some damaged part of himself healed without gangrene? If somebody had operated on him, he had no idea where.

Laz reached up, straight out in front of his chest, and his hands almost instantly bumped into some kind of ceiling or lid or cap. It felt like plastic; it had a little bit of give to it. So he was in a sealed environment, though he didn’t feel claustrophobic or even particularly warm. He was definitely a claustrophobe. The time his mother rented an RV and invited him to sleep on one of the bunk beds, he couldn’t sleep that night at all. He didn’t complain, though. His mother loved the RV. And Laz didn’t want to ruin it for her.

He was only about eleven, maybe ten—before she remarried, so he knew that this RV experiment was meant to provide his mother with some kind of bonding opportunity. But when he asked her if he could please stay home instead of gallivanting along all summer, she seemed stricken. She also wanted to feel like a good mother. Now she felt like she had failed.

So Laz figured he had no choice but to side step into a timestream in which his mother had decided not to rent the RV after all. While Laz always remembered the alternate timestreams that he had lived through, even for a single hour, he knew that he had to make sure she never got back on this RV kick again. Now his mother had no idea she had ever rented an RV, and there was no timestream in which Laz told her how claustrophobic he was in an RV bunk bed. As long as she didn’t get another RV, there was no need ever to have that conversation.

Here he was now, reaching out for timestreams that did not provide him with any alternatives at all. Just waking up, feeling the thin plastic mattress, seeing his arm only vaguely in the green light, feeling the plastic lid arching over his bed—box? Container? Coffin?

Got to get things moving. He pushed on the lid. It gave a little, but now he pushed harder, then shifted his hands down near the edges of the lid. This time there was no give at all on the left side, but a lot more give on the right. He pushed harder with his right hand. The lid seemed to separate from the edge of the coffin/box/chamber and rise a few centimeters, then drift down when he stopped pushing.

Now he twisted his body and got both hands to the right-hand edge and pushed upward. An awkward pose, but it worked. The lid rose fairly easily and smoothly, and once it passed about twenty centimeters above the rim, the lid raised itself the rest of the way, and then seemed to slide down into the wall of the coffin.

He sat up. He couldn’t see anything. The green light from the message panel did not illuminate anything outside his box.

Then, when he looked to the left, he saw a lot of blurry, twinkling green lights extending in a direct line away from his own instrument panel. And others, in other rows, above the head of his box and below the foot.

He looked back the other way and saw no lights, but he understood why. His own coffin only had a light on the left side. Therefore if there were boxes extending away on his right, all their green lights would be hidden behind the left wall of each chamber. He could be in the exact center, but only boxes to his left would reveal themselves to him.

Why hadn’t somebody turned on the lights? Why didn’t some kind of generalized lighting come on when his coffin lid opened? At least some mechanical voice could have said, You are fully healed now, Lazarus Hayerian; your parents will arrive to pick you up and take you home within the hour.

Who designed this unfriendly system? Who decided to let somebody wake up with no greeting, no guide, no explanation?

Why couldn’t he remember getting in this box? Or going in for some kind of treatment? Since he had always been able to avoid illness or accident by side stepping into a timestream where he hadn’t caught the disease or hadn’t made the choices that got him in the way of the accident, for him to be sick enough to need incarceration in a box like this one would have been memorable. He felt his abdomen, arms, shoulders; no sign of a healed injury or any kind of scar.

He remembered that he did have a kind of marker on his body. It was a weird toenail growth on his left little toe that had been there since he was four and would never go away. “Nonthreatening,” said every doctor who looked at it, “so clip it if it gets big, there aren’t any nerves in it, and wear socks.” Laz reached with his right foot, rubbed it over the warty toe.

That growth was missing. Just a normal nail on the little toe.

What was really going on? Why would any hospital remove that warty growth on his toe? Accident or no accident, why would they include that in their treatment? Or did the healing box handle it automatically, because genetically it wasn’t supposed to be there?

Laz started pressing every spot on the display panel but nothing gave him any feedback. There were no unlighted buttons or switches or levers, either. Whatever controls this healing cave had, they were on the outside of the box—which made sense, since a patient might accidently hit one of them in his sleep, and no medical professional would allow a patient to have a significant vote on his own treatment.

Maybe he had an illness or accident that attacked his brain and made him unconscious for a while. Then he wouldn’t have memories of it.

His dreams had been an array of memories, playing out in almost random order. And it occurred to him that this box might not have been a healing chamber at all. Maybe his dreams came from recorded memories being played into his brain, his empty brain, because he wasn’t actually the real Lazarus Hayerian. Maybe he was a copy.

He didn’t know whether to be excited or dismayed. How far had cloning technologies advanced? Cloning nonverbal animals didn’t allow for questionnaires about how well the clone remembered being the original animal, though they had experimented with memory recording and playback in sheep, pigs, dogs, and baboons—he had read about that stuff.

Did those experimental clones feel what he was feeling now, with memories forced on him, pushed to the front of his mind, but in no rational order?

While he was thinking, Laz did an ab crunch, and felt that his muscles were taut and strong. It was a feeling of strength beyond anything he’d ever felt before. He was a leisurely hiker, but summers of hiking everywhere left him with a decent core and great thighs and glutes and calves. But now his belly was as tight as a swimmer’s. As a gymnast’s. And sitting up from mid-crunch wasn’t just easy, it was almost automatic. He was built to make this move; it required no particular exertion.

Still, it wasn’t easy to get out of the box. The sides weren’t more than fifteen centimeters high, but that was still an awkward lip to get his feet outside and over, and then raise himself up and slide his bare thighs and butt across the edge.

He was glad that however long he had spent in the box, his muscles hadn’t atrophied. Once he was standing up on the cool hard floor, rubbing his buttocks and thighs to help get over the scraping they had just had, he realized that in some ways he was in better shape than ever. His arms and chest were well muscled and he had very little body fat—for the first time in his life, he actually had washboard abs.

But, feeling his thighs and calves, he realized that these could not be his own legs. His calves were ropy and wiry, his thighs well developed, his glutes tight from having spent all his teenage years taking long, long walks, many times over the mountains from the Valley down into Hollywood or Beverly Glen or to the houses of some of his friends in Brentwood or Highland Park, or even, once or twice, to Malibu or Topanga Canyon.

Southern California was full of long distances that required grown-ups to drive everywhere—but a kid like Laz, with no responsibilities and no fears, had all the time in the world to walk. Nobody ever accosted him or caused him grief, because any situation that had the potential to be dangerous or even just annoying caused Laz to side step into a timestream where the obstacle wasn’t present.

He looked into his parallel timestreams and saw that in some of them, he had already discovered the packet of lightweight clothing on a shelf built into the head of his coffin. It fit loosely. It felt like paper. But it wasn’t uncomfortable.

He could imagine his nonexistent guide explaining, We can’t be sure if any of our clients are allergic to various fabrics, so we made our wakeup clothing out of hypoallergenic paper. If this causes you any discomfort, or if the fit is not just right, merely tell me and I’ll bring you a replacement. We have cotton, rayon, silk, and hemp, though all of those are heavier and warmer than the paper.

There was no guide. But there was a paper costume, and it covered his body adequately. Unlike the normal hospital gown, which left your butt open to the air so you could get injected or bedpanned without formalities, these were genuinely modest.

Or at least no less modest than the pajamas his grandparents sent him every Christmas. Those always had two-snap flies, so that either you flashed other people every time you sat down, making the fly gape open above and below the middle snap, or you wore underwear, so that there was no particular reason for you to have the pajamas at all, since underwear was fine for sleeping in.

Dressed now, right down to the lightweight slippers on his feet, he rested his left hand on the lip of his own coffin and reached out with his right hand. The next coffin was close enough he didn’t have to reach very far.

He leaned over that new coffin and found that it, too, had a green light, though the only numbers it showed were zeroes. He could see the other person’s arm.

Only it wasn’t an arm. It was a radius and ulna, with a humerus above the elbow. There was still some tissue there, stretched like parchment between the bones. Whoever was in that box, they weren’t alive.

Laz suppressed ridiculous thoughts like the zombie apocalypse, which he thought would be even less likely to happen than the Christian rapture. He was still in the real world, where dead was dead.

Could the people here be prisoners? Was this a prison that kept its inmates in boxes where they could be sedated automatically? A prison where three consecutive fifty-year sentences could be served, even if you died thirty years into it. No wonder he woke up feeling groggy.

“Excuse me,” he said aloud.

No, that’s what he meant to say. What he said was more like a strangled whispery cough. He cleared his throat. Some phlegm came up and he didn’t know what to do with it. Spit it onto the grimy floor? That felt too piggish—he was indoors, after all—and he certainly wasn’t going to spit it into his bed. So he swallowed it. Which was difficult because his mouth and throat were really dry.

He hadn’t been aware of thirst, but he certainly needed to get some water into his mouth and throat.

“Excuse me,” he tried again. This time if someone had been there, they might have understood his words. “Drinking fountain, anyone?” he asked. “Bottled water? Don’t care about the brand. Room temperature is fine.”

No sound came back to him; there wasn’t even an echo.

Either he was alone in a room full of healing boxes, or the observers could see him through heat-sensing lenses or infrared scopes and were watching to see what he would do.

Well, what would he do? Sleeping in that box hadn’t hurt him at all—every joint was working smoothly, every muscle clearly had more power than he had ever felt. He thought he could run a marathon. He thought he could do a hundred chin-ups in a row. If the floor weren’t filthy, he’d drop and do push-ups until he got tired of it, and the way he felt right now, that would be never. So whatever his silent observers had done, they hadn’t tortured him, they hadn’t weakened him.

Nobody was watching. He was alone in the room.

Unless Laz could find another timestream in which the other boxed-up human was not dead.

He couldn’t. The timestreams were slightly different now. He dressed more quickly in some than in others. He had already found that his right-hand neighbor was dead in some, and he had not yet checked in others. But there was no reason to make a change, because none of the timestreams had any lights on, or any explanatory signs, and certainly no helpful attendants to make his waking up ceremonies more pleasant or understandable.

I’m a clone, Laz decided. Nothing else made sense.

Of course, being a clone didn’t make sense, either. The process was still experimental and ridiculously expensive. Only the most important people in the world were having their DNA stored and new bodies grown. Not teenagers in SoCal whose sole contribution to humanity was walking every road, sidewalk, bike path, and trail from Oxnard to Koreatown. Who would be crazy enough to clone him?

His parents had a little money, but not like that. Plus, shouldn’t he remember at least some kind of discussion about being cloned?

I can’t figure out anything standing here. The fact that the lights in the coffins were on—even the ones that were zeroed out—suggested that this building had electric power, so that in the rooms where employees worked there were bound to be lights and explanations. Why not look for the light switch in here?

If he just started walking in any direction and kept going, he would eventually come to a wall, because this was an enclosed space and something was holding up the ceiling and keeping wind and weather out. Come to a wall and follow along until you come to a door. Open it if you can, walk through. Or at least search along the walls near the doors to find a light switch. That’s where people put light switches, so they could turn them on as they entered the room.

The pulse display inside the healing cave showed his heart rate as forty-one. But now that he was outside the box and moving around, it must be reporting his last inside-the-box reading.

He put one hand on the long side of his healing cave, and the other hand on the side of the adjacent box. Then he started walking in the direction where his feet had been pointed inside the box. That was “down” and it was a direction, so why not?

Laz tried to count the boxes and he believed he was at fifteen when he thought, No, thirteen, and then he didn’t know anymore. He stuck with fifteen.

At eighteen—or sixteen?—the boxes ended. At this point there was no light at all. The wall might be one meter or a hundred meters away. There might be a steep drop-off, though why there would be he couldn’t guess.

If he got disoriented maybe he’d walk in circles in the dark and never find his way back. But if that happened, he could side step to a reality where he went in a different direction from his healing cave. It was sometimes wrenching to make such a shift, but apart from the concentration it required, it cost him nothing, so he never had to live long with the consequences of bad choices.

He had spent half of fifth grade thinking of ways that he could die without being able to side step in time. Like if somebody sprang from ambush and bashed him in the head with a meat tenderizer, immediately rendering him unconscious. They could stay there beating him until his brain was tartare on the sidewalk, and he would never be awake enough to side step.

Nobody wanted to kill him.

But if somebody did, there would be ways.

Back to his dilemma in the dark in the tomb room. What if no direction led anywhere useful? Would he then return to his healing cave? Take the clothes back off, fold them neatly, and get inside again? He couldn’t pull down the lid because it had slid into some neverland without a trace. Should he choose a reality in which he never caused the lid to open? Then what, wait some long or even infinite time for somebody to notice he was awake?

Why should he go back? He was blind now, but he was blind back there, too, and he wouldn’t learn anything by sitting around. If there were wardens or alien zookeepers watching him (he was flashing now on every movie and TV show he had ever seen) they should at least see him try to add more information to his meager supply.

He used gentle pressure from his fingers to push off simultaneously from both boxes under his hands, and tried to keep a steady direction as he moved out into nothingness. At first he felt gingerly with his toes before taking a step, but that was slow going, and if there was a precipice, he’d find out no matter how careful he was. Maybe there’d be a handrail. Dad worked in risk management for a school district—he would have made the schools put in handrails or guardrails on any floor that led to a drop-off or downward stairs.

How many steps? He hadn’t counted. Eighteen boxes, but no idea how many steps he had taken after leaving them behind.

His foot kicked something. A wall. The slipper offered scant protection, so Laz was relieved that he had been walking so gingerly. He wouldn’t have wanted to jam a toe.

It was a full-height wall, as high as he could reach. Should he go left or right? Left won, so it was his right hand trailing along the wall, feeling for any kind of gap or doorjamb.

It was a doorframe. The door was closed. He couldn’t find a handle at any reasonable height.

There was no light switch or any kind of protuberance or indentation on the wall he had walked along. But on the far side of the door, there was a raised rectangle with two depressions in it, one over the other. A light switch?

He pressed the upper one.

The door opened.

There was a bright light in the corridor on the other side.

The corridor ran parallel to the wall Laz had just walked along. There were no written signs visible from where Laz was. He did not dare walk out into the corridor because the door might close behind him.

But now that some light was spilling into the big room, he could see that it was filled with row after row of healing caves—if that’s what they were.

Would the door stay open?

Laz pressed the lower button. The door closed and everything was dark again.

He pressed the upper button. The door opened back up. Light.

Leaving the door open behind him, Laz walked to the nearest healing box. Now he could see that the lid was fully transparent. That had not been obvious before, because the whole room had been dark. Now, though, there was enough ambient light for him to see that this box was indeed occupied.

By a mummy. A desiccated human shape. This time he could see the whole corpse at once.

Laz cried out and stepped back toward the corridor.

Is that what I would have become, if I had never pushed on the lid and caused it to open?

He forced himself to go back and look into the box with the corpse inside.

The display panel was there, but everything said zero. Clearly this person had not had a heart rate worth recording for a long time.

Laz went to the next box, the next, the next. If these had once been healing caves, they had failed at their function. These occupants were beyond healing.

Most of them seemed to be small. Many were child-sized. Same size box as Laz’s though, as if they were supposed to grow into them, like oversized hand-me-downs from older siblings—a concept which Laz, as an only child, had never experienced for himself.

Now as he looked out over the dim array of boxes, he knew that this was no hospital. It was more like a graveyard. All these boxes must contain dead bodies.

Why had his cave still functioned? Did these boxes all go dark because the clone inside was dead? Or did the occupants die because the boxes went dark?

Why am I alive? And why hasn’t anyone come to meet me? To yell at me for getting out of my box without permission? It would be nice to get into a brisk argument with some idiotic adult who was castigating him for not obeying rules that Laz had never heard of.

Laz enjoyed arguments in which the opponent was locked into positions whose absurdity made it impossible for them to speak sensibly. Other kids would give up and walk away—or get mad and jab at him. But adults always had a completely unjustified certainty that if they just talked long enough at a younger person, they would prevail.

In this case, Laz would have liked the argument for a completely different reason: It would mean that there was another person present. It would mean he was not alone.

Laz walked back to the open door and stepped halfway through, one foot inside, one outside of the room. He saw controls for the door on the outside, too.

He would have to try the outside buttons. If they did not work and the door closed behind him, then he could decide whether to side step into a reality in which he had not chosen to step outside, or just live with the decision and continue exploring the building.

He pressed one set of buttons and the door closed and reopened. He pressed the other, and bright ceiling lamps flooded the interior of the huge room with light.

It turned out the corridor lights had not been bright at all—in fact, they were as dim as the EXIT lights in a theater. Laz realized that even the lights now illuminating the room were probably not all that bright—his eyes just weren’t accustomed to having light at all.

His impressions of the big room had been correct. By chance he had gone the shortest way from his healing cave to the nearest wall; there had to be upwards of fifty rows in every direction. He could see that there were doors about every thirty meters along the walls, leading somewhere. It wasn’t Laz’s job to find out where, unless it turned out that this corridor led nowhere.

Laz turned off the light. He closed the door. Maybe there was another functioning healing cave inside another room, and maybe he would locate it and find a living human being.

Later. First he needed to find out where everybody was. Who was in control of this operation.

No. First he had to find a drink of water.

In the course of wandering around the corridors, he found two drinking fountains, but the chilling unit wasn’t working in either one, and when he pressed the button, water didn’t flow. It didn’t even dribble out. The water seemed to have been cut off.

But I didn’t dry out in my box, thought Laz. Moisture got to me somehow. My box kept me alive. Something in this place is still working.

The corridors formed a maze—or maybe it was a perfectly consistent pattern that he just didn’t understand. There were doors in other walls, but they didn’t respond to a button press.

Then it dawned on him that there was something else that none of the walls had.

Windows.

Maybe he was underground.

He went to the end of a wide corridor. It butted up against a wall.

To the left and right, though, there were buttons. No doors, no numbers, no labels, just buttons. He pressed one.

The whole floor, from the end wall to about six meters out, rose smoothly. A low wall appeared on the outside edge, enough to keep a rolling cart from falling off. The ceiling parted above him. He went past another floor, with dimly lighted corridors. This time when the ceiling above the elevator platform opened, there was a much brighter light. It was daylight, Laz knew, simply from the quality of the light. Nothing artificial. Sun through glass, that’s what he was seeing.

The floor with his healing cave was two floors below daylight.

The elevator stopped—apparently this was as high as it went. The low barrier wall was gone. Laz stepped out into the sunlit corridor, which quickly led to a large open glass-walled reception area.

There was nobody at the reception desk. Nobody at the doors. Nobody on the furniture.

And not much furniture, either. It was as if all the good pieces had been removed, and only the ones with tatty upholstery were left. Like at an underfunded school.

There had once been electronic equipment at the reception station, but all that remained were sockets of various kinds.

This place screamed, Out of business.

Yet one of those healing caves two floors down had contained a living person. Did you all just forget me?

There were big letters on the glass wall. They were backward—they were sending their message out onto the street. But Laz easily read them, though he had to walk through the large open space for a while before he was sure he had seen all the letters.

From the outside, passersby would have read the word “Vivipartum.” It sounded like a company name. Laz thought through his Latin roots and figured that it might mean something like “born alive.” He had once had “parturition”—birth—as a vocabulary word, and “vivid” clearly was related to life.

And that was his confirmation of what this place was. Not a hospital at all. Not even a retirement home for dying people hoping to be kept alive till there was a cure.

He remembered the articles and essays and op-eds and diatribes and slogans from three or four years ago, when the technology for cloning and fast-growing human bodies had been developed. At that time, cloning was justified solely as a means of supplying organs and limbs for the genetic owner, in case things went badly and a transplant was needed. No more hoping for a liver donor or heart donor, no more matching blood types and using immunosuppressants. All transplant needs were met using organs and limbs that were genetically identical to the transplant recipient.

The clones will never be brought to consciousness, the proponents assured everyone. They will never have legal existence as people. They are not citizens. They are organ and limb banks, with individual proprietors whose DNA had been used to create them.

Meanwhile, religions were in a frenzy over the question of whether clones had souls, whether they were tainted by original sin, whether they were eligible for redemption. They were never alive and could not be resurrected; they were definitely alive and to kill one in order to harvest a vital organ was murder. So many people were sure that their view was the only one a decent person could have.

This was all mildly interesting to Laz as a kid. He remembered that the courts had allowed cloning and harvesting to continue, under the legal theory that clones never achieved consciousness or acted upon their own volition in any way, and were therefore nonpersons in the eyes of the law. Property.

The controversy didn’t die down completely, so the big cloning corporations spun off the cloning operations into a lot of smaller companies with different names. They all pretended to be in another line of work, and most of them actually conducted other businesses.

In this Vivipartum building, all the rows of boxed clones were underground.

Maybe when the owners of the clones stopped making their payments, the life support was cut off and the clones all died. That made sense to Laz. These weren’t people, so nobody cared if they died.

But somebody had kept up payments on Laz’s body, so he lived.

And something else. The clones were never supposed to achieve sentience or volitional behavior. Yet here was Laz walking around, full of memories of a childhood that this body had never lived through. If he was in fact a clone.

He was a clone with a memory.

Had the technology moved forward, without anybody reporting on it? Could they take the memories out of the original owner’s brain and then play them into the brain of the clone? Laz had never heard of such a technology, but then, after the huge brouhaha about cloning in the first place, the companies would keep such a development completely under wraps, because it would reopen the whole person/nonperson debate again, and who knew where the courts would land?

Laz had not been cloned to provide body parts for some older version of Laz. Laz had been given the memories of his life up to age seventeen. Laz was being prepared to be a replacement.

Ridiculous. Why replace somebody who wasn’t dead? If his older original self had died, they could only revive him if they had recorded his memories while he was alive. Laz had no memory of that. If somebody judged a teenager like him to be important enough to record, Laz would not have forgotten it.

If his original self was alive, why would they be prepping Laz to replace him?

Maybe they now put memories into all the clones. Maybe so that they could do a brain transplant, if that was necessary. And it was just random chance that Laz’s clone had survived when so many others downstairs had died.

Maybe I’m not a clone at all. Maybe I’ve read this whole situation wrong.

In the whole time he had been standing in the glass-walled reception area, not a single vehicle had passed by on the street outside.

Laz walked to the window, then to another spot in the glass wall, and he saw that the parking lot wasn’t empty. There were a few cars in it, but they were parked any which way. Like nobody cared. And there were a couple of cars with people in them, but they weren’t moving. Neither the cars nor the people.

There were crash bars on the doors—strictly according to fire code—but Laz was afraid again that once he went through the doors and let them close behind him, he wouldn’t be able to get back in. Besides, he didn’t know if the weather outside was sunny and hot or sunny and cold. He sure wasn’t dressed for cold.

He pushed open the outside door. A blast of air came in. Cold. But not bitterly cold. Colder than Los Angeles. More like San Francisco standing near the water.

Holding one door open, he pulled on the handle of the other. Locked.

He looked for a way to unlock it. If nobody had noticed him so far, he wasn’t going to count on being able to knock on the door and have somebody let him back in. He stepped back into the doorway and looked for a way to unlock the door mechanically. No such.

So he pulled one of the tatty sofas over to the door and awkwardly pushed it out between the two doors, to hold them both open. Surely this would bring some kind of security guy into the reception area.

It didn’t.

Laz went outside and walked toward a car with a guy in it.

A dead guy. A guy who had been dead for a long time. A guy with a smashed-in head. Or a blasted head. There was no gun in the car, though, if he had killed himself.

The other car had a couple in it. Also dead. A long time dead. And a bottle that must have held pills. Suicide?

The other cars were all empty.

How long ago had they died? Why hadn’t anybody cleaned up the mess? Why had three people chosen the same parking lot to kill themselves, one by gunshot and two by overdose? And who had removed the gunshot guy’s pistol? Why had they left the empty pill bottle? Somebody had done some cleanup, yet they had left these corpses.

For me to find? thought Laz.

It’s not about you, Laz could hear his mother saying. Don’t be such a drama queen, Laz. The world doesn’t revolve around you.

But what if nobody else was ever going to come out of that building to this parking lot? thought Laz.

The pill guy was wearing a jacket.

Could Laz wear a jacket whose owner had rotted away inside it?

A gust of wind told him, Yes, he could, because it was cold out here. He would try to replace it with something not so disgusting as soon as he could.

The car door opened when he pulled on the handle. Not locked. Laz tugged on the jacket. The body kind of fell apart inside it. Much of the body came out of the car with the jacket, but then fell out of it onto the asphalt. Laz felt a moment of nausea, a moment of horror, but he knew that the people in this car did not pose any danger to him, so he paused a moment to let his rational mind take control again.

Laz unzipped the jacket, shook it, beat it against the car to get all the body parts out of it. Then he pulled it on. It didn’t smell. Well, it did, but not as bad as the inside of the car had smelled, and he could stand it. It blocked the wind. It was long enough to protect Laz’s butt and privates as well as his stomach and chest and arms. It would keep him from dying of exposure wearing paper clothing out here.

Was that why they left these bodies? For him? So he’d realize there had been some kind of cataclysm, that civilization had ended and bodies were left where they died—and so that he could also salvage important articles of clothing from the corpses?

They could have left him a note and a nice warm set of clothes.

He reached back into the car and felt in the guy’s pockets, trying not to stare down into the pelvic cavity surrounded by the waistline of the pants.

Nothing. No wallet, no car keys. No keys in the ignition, though he realized that this car would certainly have had a proximity key.

He went around to the other side because he saw the woman had a purse. He opened it. What would he do with a makeup compact? It had a mirror in the lid. He closed it, put it in his jacket pocket. There was also a small pocket knife. That might come in handy. But that was all. Surely women carried more than this in their purses.

Missing car keys. Missing wallet, missing money, missing almost everything. Somebody had taken from these bodies everything they didn’t want Laz to have. He was allowed to have a small knife and a mirror. He could have a jacket. Nice of them.

He shuddered in the chilly breeze and gathered his thoughts. These things were not directed at him, at Lazarus Davit Hayerian, seventeen-year-old high school senior and smart mouth extraordinaire. Beware narcissism, you stupid heap.

No, this was not according to somebody’s plan, or at least not a plan for him. Laz just happened to wake up right now and happened to be the person who found these bodies and these things.

But somebody took everything from the guy’s pockets and most things from the purse. Somebody had taken the pistol from the guy who shot himself.

And in these cars, in the building, there hadn’t been a scrap of paper with any writing on it. Not a book, not a pamphlet, not a newspaper, not a magazine on the tables in the reception area, not a wad of trash or packaging tumbleweeding down the street in the breeze.

There was nothing to show him the date. Nothing to show even the year. The weather told him it was during a cold season, but Laz didn’t know enough about the sky to judge from the position of the sun whether it was the dead of winter or near one of the equinoxes. Nor could he guess where he was. The name Vivipartum didn’t give him any clue to the latitude and longitude, and therefore whether this was as cold as it ever got around here, or if this was an unusually warm spell.

And still not a car had passed by on the street.

Why had everybody gone away and left him here to wake up alone?

He felt the impulse to get away, to simply leave and return to a better place. With people in it. With his people in it.

But before he could try to act on that impulse, and side step into a different set of conditions, he realized: He had learned before he was twelve years old that he could swap realities only by stepping into a version of himself that already existed in the different reality. That was a rule he had never been able to break. So whenever he side stepped, he got the whole set of memories of the version of Laz that already existed in that reality, plus his memories of the reality he had left behind.

If he was really a clone, though, then there was no version of him in any other reality. He and his original were not the same person, regardless of DNA or physical appearance or shared memories. He couldn’t side step to get out of this situation, because this was the only reality in which he, Clone-Laz, had ever existed.

Then again, what if he was wrong?

He tried to side step, but couldn’t find within his mind any other reality to move to, apart from realities since his waking, in which he was still inside the building, still in the dark, exploring a different wall, lying in the healing cave, walking along different corridors without realizing that there had to be elevators, or shivering in the wind without wearing the dead man’s coat. Petty local differences. Nothing to move him out of this abandoned place. Nothing to put him in living human company.

He was stuck here.

No internet, no blogging. Since I may be the last human being on Earth, there’s nobody to read the blog anyway. Of course, there might be five billion people in Asia, for all I know. But since I haven’t found a working computer since I woke up, I can’t post anything for them to read.

I’m going crazy not having anybody to talk to. I’m beginning to realize that I actually did need friends back in school. I just didn’t notice the fact because I had friends.

So I’m inventing a new thing: the plog. Paper blog. I know, “blog” is itself a conflation of “biographical” and “log,” but it’s a word on its own now. Or it was back when I was alive. (Not sure yet if what I’ve got here is actually living.)

I got the idea of doing this when I broke into a Staples and found that the reams of paper that were wrapped in plastic had survived. So then I started trying pens. They were all dried out, even with their caps on. Paper-eating fungi, bacteria, and the moisture from this damp climate that seeps its way in wherever it can doomed the cardboard. The half-cardboard part of the packaging on the pens crumbled under my fingers. I remember you used to need heavy shears, a sturdy sharp knife, or lightning from heaven to get those packages open in the old days. Now they tear open like toilet paper. Like damp toilet paper.

So I tried mechanical pencils, because you don’t have to sharpen them. But all the mechanisms are either frozen or completely ineffective. If the lead can’t be advanced and then stay in place, you don’t have a pencil, you have a stylus. And even when it did advance, it kept breaking. Really, crumbling. Becoming a smudge of graphite dust on the paper.

You know what I’m writing this with? A regular old-fashioned wooden pencil with an eraser on the end. The eraser is brittle and crumbles pretty easily, but for a while at least it worked, and it doesn’t matter anyway because I’m not going to erase anything, I’m just putting down whatever comes into my head like I’m talking to you instead of writing to you, because I don’t know if you, my future reader, will ever exist.

Here’s the thing. Wooden pencils don’t have any mechanical parts that will rust. Of course fungi and bacteria have been dining out on this pencil, but it still works anyway. And instead of a clunky mechanical sharpener, which I wouldn’t want to lug around anyway, you know what works great? Those cheapo little plastic sharpeners with a razor blade in them to shave the pencil point at the correct angle. I carry a couple of those in my backpack now, along with a dozen pencils, and I have to remind myself that this ancient technology only came into existence in, like, the seventeen hundreds. Or the seventeenth century. Who cares when, but the Romans didn’t have them, and the Babylonians and Egyptians and ancient Chinese didn’t have them, and paper itself is only about a thousand years old or so, and that’s all I remember from a couple of reports in school. Not mine, some other kids’ reports, so this is proof I was awake and I did listen.

BECAUSE HE WAS a teenager, and teenagers take pleasure in exploring wacky ideas, Laz Hayerian had wondered since the sixth grade whether we are the same person when we wake up that we were when we went to sleep. Specifically, he wondered if he was the same person, because sometimes his dreams persisted in memory as if they had been real events. Did dream memories change him the way real memories did?

This always led to the deeper question: Since Laz had memories that came, not from dreams, but from timestreams he had stepped out of, did his intertwined memories of other realities make him less sane? Or more experienced? Or both?

Since, as far as he knew, no one else in the world had the ability to side step from one timestream to another, there was no one he could ask, and no philosopher who had written about it.

As he woke up this morning—morning?—he felt very strange, and it wasn’t the residual effect of some dream. He didn’t even remember dreaming. It was his own past that felt like a disjointed dream, as if sometime in the night his whole life played out in his mind, but completely out of order, an incoherent scattering of scenes, facts, feelings, people, places.

When he opened his eyes, he was in nearly complete darkness. Even on mornings at Dad’s place, there was always plenty of light that seeped around the curtains.

All he could see was a tiny amount of green light coming from a few inches to his left.

He was lying on a plastic mattress that felt no more cushioned than the pad in the bottom of a portable crib. Yet he didn’t feel any aches or sore spots, and when he flexed muscles up and down his body, nothing caused him pain.

So Laz did what he had always done since his earliest memories of childhood. He searched for the alternate paths through time that were always close enough for him to take hold and shift, changing the story of events in bold or barely perceptible ways. It didn’t matter which, as long as it got him into a place where things made more sense.

For the first time in his life he could not find any of the alternate timestreams.

No, no, he was finding them, yes, thousands of them—as always. Only none of them went back even a moment earlier than the moment he woke up just now. And none of them showed him doing anything different, so there was no point in side stepping from one to another.

He was afraid. He had never reached out and found that all his pasts and all his futures were identical. It meant he had no choices. Whatever was going on right now, he was like other people—he was trapped.

He didn’t like feeling trapped.

Why was he feeling trapped? He extended his hands away from his sides and they bumped into solid walls. He was in an actual container.

The green light came from some LED letters and numbers on a panel at his left side, inside the box, but he didn’t know what any of them meant. Someone else would explain them to him. If he was in some kind of—what? A medical treatment chamber? An anti-infection box while some damaged part of himself healed without gangrene? If somebody had operated on him, he had no idea where.

Laz reached up, straight out in front of his chest, and his hands almost instantly bumped into some kind of ceiling or lid or cap. It felt like plastic; it had a little bit of give to it. So he was in a sealed environment, though he didn’t feel claustrophobic or even particularly warm. He was definitely a claustrophobe. The time his mother rented an RV and invited him to sleep on one of the bunk beds, he couldn’t sleep that night at all. He didn’t complain, though. His mother loved the RV. And Laz didn’t want to ruin it for her.

He was only about eleven, maybe ten—before she remarried, so he knew that this RV experiment was meant to provide his mother with some kind of bonding opportunity. But when he asked her if he could please stay home instead of gallivanting along all summer, she seemed stricken. She also wanted to feel like a good mother. Now she felt like she had failed.

So Laz figured he had no choice but to side step into a timestream in which his mother had decided not to rent the RV after all. While Laz always remembered the alternate timestreams that he had lived through, even for a single hour, he knew that he had to make sure she never got back on this RV kick again. Now his mother had no idea she had ever rented an RV, and there was no timestream in which Laz told her how claustrophobic he was in an RV bunk bed. As long as she didn’t get another RV, there was no need ever to have that conversation.

Here he was now, reaching out for timestreams that did not provide him with any alternatives at all. Just waking up, feeling the thin plastic mattress, seeing his arm only vaguely in the green light, feeling the plastic lid arching over his bed—box? Container? Coffin?

Got to get things moving. He pushed on the lid. It gave a little, but now he pushed harder, then shifted his hands down near the edges of the lid. This time there was no give at all on the left side, but a lot more give on the right. He pushed harder with his right hand. The lid seemed to separate from the edge of the coffin/box/chamber and rise a few centimeters, then drift down when he stopped pushing.

Now he twisted his body and got both hands to the right-hand edge and pushed upward. An awkward pose, but it worked. The lid rose fairly easily and smoothly, and once it passed about twenty centimeters above the rim, the lid raised itself the rest of the way, and then seemed to slide down into the wall of the coffin.

He sat up. He couldn’t see anything. The green light from the message panel did not illuminate anything outside his box.

Then, when he looked to the left, he saw a lot of blurry, twinkling green lights extending in a direct line away from his own instrument panel. And others, in other rows, above the head of his box and below the foot.

He looked back the other way and saw no lights, but he understood why. His own coffin only had a light on the left side. Therefore if there were boxes extending away on his right, all their green lights would be hidden behind the left wall of each chamber. He could be in the exact center, but only boxes to his left would reveal themselves to him.

Why hadn’t somebody turned on the lights? Why didn’t some kind of generalized lighting come on when his coffin lid opened? At least some mechanical voice could have said, You are fully healed now, Lazarus Hayerian; your parents will arrive to pick you up and take you home within the hour.

Who designed this unfriendly system? Who decided to let somebody wake up with no greeting, no guide, no explanation?

Why couldn’t he remember getting in this box? Or going in for some kind of treatment? Since he had always been able to avoid illness or accident by side stepping into a timestream where he hadn’t caught the disease or hadn’t made the choices that got him in the way of the accident, for him to be sick enough to need incarceration in a box like this one would have been memorable. He felt his abdomen, arms, shoulders; no sign of a healed injury or any kind of scar.

He remembered that he did have a kind of marker on his body. It was a weird toenail growth on his left little toe that had been there since he was four and would never go away. “Nonthreatening,” said every doctor who looked at it, “so clip it if it gets big, there aren’t any nerves in it, and wear socks.” Laz reached with his right foot, rubbed it over the warty toe.

That growth was missing. Just a normal nail on the little toe.

What was really going on? Why would any hospital remove that warty growth on his toe? Accident or no accident, why would they include that in their treatment? Or did the healing box handle it automatically, because genetically it wasn’t supposed to be there?

Laz started pressing every spot on the display panel but nothing gave him any feedback. There were no unlighted buttons or switches or levers, either. Whatever controls this healing cave had, they were on the outside of the box—which made sense, since a patient might accidently hit one of them in his sleep, and no medical professional would allow a patient to have a significant vote on his own treatment.

Maybe he had an illness or accident that attacked his brain and made him unconscious for a while. Then he wouldn’t have memories of it.

His dreams had been an array of memories, playing out in almost random order. And it occurred to him that this box might not have been a healing chamber at all. Maybe his dreams came from recorded memories being played into his brain, his empty brain, because he wasn’t actually the real Lazarus Hayerian. Maybe he was a copy.

He didn’t know whether to be excited or dismayed. How far had cloning technologies advanced? Cloning nonverbal animals didn’t allow for questionnaires about how well the clone remembered being the original animal, though they had experimented with memory recording and playback in sheep, pigs, dogs, and baboons—he had read about that stuff.

Did those experimental clones feel what he was feeling now, with memories forced on him, pushed to the front of his mind, but in no rational order?

While he was thinking, Laz did an ab crunch, and felt that his muscles were taut and strong. It was a feeling of strength beyond anything he’d ever felt before. He was a leisurely hiker, but summers of hiking everywhere left him with a decent core and great thighs and glutes and calves. But now his belly was as tight as a swimmer’s. As a gymnast’s. And sitting up from mid-crunch wasn’t just easy, it was almost automatic. He was built to make this move; it required no particular exertion.

Still, it wasn’t easy to get out of the box. The sides weren’t more than fifteen centimeters high, but that was still an awkward lip to get his feet outside and over, and then raise himself up and slide his bare thighs and butt across the edge.

He was glad that however long he had spent in the box, his muscles hadn’t atrophied. Once he was standing up on the cool hard floor, rubbing his buttocks and thighs to help get over the scraping they had just had, he realized that in some ways he was in better shape than ever. His arms and chest were well muscled and he had very little body fat—for the first time in his life, he actually had washboard abs.

But, feeling his thighs and calves, he realized that these could not be his own legs. His calves were ropy and wiry, his thighs well developed, his glutes tight from having spent all his teenage years taking long, long walks, many times over the mountains from the Valley down into Hollywood or Beverly Glen or to the houses of some of his friends in Brentwood or Highland Park, or even, once or twice, to Malibu or Topanga Canyon.

Southern California was full of long distances that required grown-ups to drive everywhere—but a kid like Laz, with no responsibilities and no fears, had all the time in the world to walk. Nobody ever accosted him or caused him grief, because any situation that had the potential to be dangerous or even just annoying caused Laz to side step into a timestream where the obstacle wasn’t present.

He looked into his parallel timestreams and saw that in some of them, he had already discovered the packet of lightweight clothing on a shelf built into the head of his coffin. It fit loosely. It felt like paper. But it wasn’t uncomfortable.

He could imagine his nonexistent guide explaining, We can’t be sure if any of our clients are allergic to various fabrics, so we made our wakeup clothing out of hypoallergenic paper. If this causes you any discomfort, or if the fit is not just right, merely tell me and I’ll bring you a replacement. We have cotton, rayon, silk, and hemp, though all of those are heavier and warmer than the paper.

There was no guide. But there was a paper costume, and it covered his body adequately. Unlike the normal hospital gown, which left your butt open to the air so you could get injected or bedpanned without formalities, these were genuinely modest.

Or at least no less modest than the pajamas his grandparents sent him every Christmas. Those always had two-snap flies, so that either you flashed other people every time you sat down, making the fly gape open above and below the middle snap, or you wore underwear, so that there was no particular reason for you to have the pajamas at all, since underwear was fine for sleeping in.

Dressed now, right down to the lightweight slippers on his feet, he rested his left hand on the lip of his own coffin and reached out with his right hand. The next coffin was close enough he didn’t have to reach very far.

He leaned over that new coffin and found that it, too, had a green light, though the only numbers it showed were zeroes. He could see the other person’s arm.

Only it wasn’t an arm. It was a radius and ulna, with a humerus above the elbow. There was still some tissue there, stretched like parchment between the bones. Whoever was in that box, they weren’t alive.

Laz suppressed ridiculous thoughts like the zombie apocalypse, which he thought would be even less likely to happen than the Christian rapture. He was still in the real world, where dead was dead.

Could the people here be prisoners? Was this a prison that kept its inmates in boxes where they could be sedated automatically? A prison where three consecutive fifty-year sentences could be served, even if you died thirty years into it. No wonder he woke up feeling groggy.

“Excuse me,” he said aloud.

No, that’s what he meant to say. What he said was more like a strangled whispery cough. He cleared his throat. Some phlegm came up and he didn’t know what to do with it. Spit it onto the grimy floor? That felt too piggish—he was indoors, after all—and he certainly wasn’t going to spit it into his bed. So he swallowed it. Which was difficult because his mouth and throat were really dry.

He hadn’t been aware of thirst, but he certainly needed to get some water into his mouth and throat.

“Excuse me,” he tried again. This time if someone had been there, they might have understood his words. “Drinking fountain, anyone?” he asked. “Bottled water? Don’t care about the brand. Room temperature is fine.”

No sound came back to him; there wasn’t even an echo.

Either he was alone in a room full of healing boxes, or the observers could see him through heat-sensing lenses or infrared scopes and were watching to see what he would do.

Well, what would he do? Sleeping in that box hadn’t hurt him at all—every joint was working smoothly, every muscle clearly had more power than he had ever felt. He thought he could run a marathon. He thought he could do a hundred chin-ups in a row. If the floor weren’t filthy, he’d drop and do push-ups until he got tired of it, and the way he felt right now, that would be never. So whatever his silent observers had done, they hadn’t tortured him, they hadn’t weakened him.

Nobody was watching. He was alone in the room.

Unless Laz could find another timestream in which the other boxed-up human was not dead.

He couldn’t. The timestreams were slightly different now. He dressed more quickly in some than in others. He had already found that his right-hand neighbor was dead in some, and he had not yet checked in others. But there was no reason to make a change, because none of the timestreams had any lights on, or any explanatory signs, and certainly no helpful attendants to make his waking up ceremonies more pleasant or understandable.

I’m a clone, Laz decided. Nothing else made sense.

Of course, being a clone didn’t make sense, either. The process was still experimental and ridiculously expensive. Only the most important people in the world were having their DNA stored and new bodies grown. Not teenagers in SoCal whose sole contribution to humanity was walking every road, sidewalk, bike path, and trail from Oxnard to Koreatown. Who would be crazy enough to clone him?

His parents had a little money, but not like that. Plus, shouldn’t he remember at least some kind of discussion about being cloned?

I can’t figure out anything standing here. The fact that the lights in the coffins were on—even the ones that were zeroed out—suggested that this building had electric power, so that in the rooms where employees worked there were bound to be lights and explanations. Why not look for the light switch in here?

If he just started walking in any direction and kept going, he would eventually come to a wall, because this was an enclosed space and something was holding up the ceiling and keeping wind and weather out. Come to a wall and follow along until you come to a door. Open it if you can, walk through. Or at least search along the walls near the doors to find a light switch. That’s where people put light switches, so they could turn them on as they entered the room.

The pulse display inside the healing cave showed his heart rate as forty-one. But now that he was outside the box and moving around, it must be reporting his last inside-the-box reading.

He put one hand on the long side of his healing cave, and the other hand on the side of the adjacent box. Then he started walking in the direction where his feet had been pointed inside the box. That was “down” and it was a direction, so why not?

Laz tried to count the boxes and he believed he was at fifteen when he thought, No, thirteen, and then he didn’t know anymore. He stuck with fifteen.

At eighteen—or sixteen?—the boxes ended. At this point there was no light at all. The wall might be one meter or a hundred meters away. There might be a steep drop-off, though why there would be he couldn’t guess.

If he got disoriented maybe he’d walk in circles in the dark and never find his way back. But if that happened, he could side step to a reality where he went in a different direction from his healing cave. It was sometimes wrenching to make such a shift, but apart from the concentration it required, it cost him nothing, so he never had to live long with the consequences of bad choices.

He had spent half of fifth grade thinking of ways that he could die without being able to side step in time. Like if somebody sprang from ambush and bashed him in the head with a meat tenderizer, immediately rendering him unconscious. They could stay there beating him until his brain was tartare on the sidewalk, and he would never be awake enough to side step.

Nobody wanted to kill him.

But if somebody did, there would be ways.

Back to his dilemma in the dark in the tomb room. What if no direction led anywhere useful? Would he then return to his healing cave? Take the clothes back off, fold them neatly, and get inside again? He couldn’t pull down the lid because it had slid into some neverland without a trace. Should he choose a reality in which he never caused the lid to open? Then what, wait some long or even infinite time for somebody to notice he was awake?

Why should he go back? He was blind now, but he was blind back there, too, and he wouldn’t learn anything by sitting around. If there were wardens or alien zookeepers watching him (he was flashing now on every movie and TV show he had ever seen) they should at least see him try to add more information to his meager supply.

He used gentle pressure from his fingers to push off simultaneously from both boxes under his hands, and tried to keep a steady direction as he moved out into nothingness. At first he felt gingerly with his toes before taking a step, but that was slow going, and if there was a precipice, he’d find out no matter how careful he was. Maybe there’d be a handrail. Dad worked in risk management for a school district—he would have made the schools put in handrails or guardrails on any floor that led to a drop-off or downward stairs.

How many steps? He hadn’t counted. Eighteen boxes, but no idea how many steps he had taken after leaving them behind.

His foot kicked something. A wall. The slipper offered scant protection, so Laz was relieved that he had been walking so gingerly. He wouldn’t have wanted to jam a toe.

It was a full-height wall, as high as he could reach. Should he go left or right? Left won, so it was his right hand trailing along the wall, feeling for any kind of gap or doorjamb.

It was a doorframe. The door was closed. He couldn’t find a handle at any reasonable height.

There was no light switch or any kind of protuberance or indentation on the wall he had walked along. But on the far side of the door, there was a raised rectangle with two depressions in it, one over the other. A light switch?

He pressed the upper one.

The door opened.

There was a bright light in the corridor on the other side.

The corridor ran parallel to the wall Laz had just walked along. There were no written signs visible from where Laz was. He did not dare walk out into the corridor because the door might close behind him.

But now that some light was spilling into the big room, he could see that it was filled with row after row of healing caves—if that’s what they were.

Would the door stay open?

Laz pressed the lower button. The door closed and everything was dark again.

He pressed the upper button. The door opened back up. Light.

Leaving the door open behind him, Laz walked to the nearest healing box. Now he could see that the lid was fully transparent. That had not been obvious before, because the whole room had been dark. Now, though, there was enough ambient light for him to see that this box was indeed occupied.

By a mummy. A desiccated human shape. This time he could see the whole corpse at once.

Laz cried out and stepped back toward the corridor.

Is that what I would have become, if I had never pushed on the lid and caused it to open?

He forced himself to go back and look into the box with the corpse inside.

The display panel was there, but everything said zero. Clearly this person had not had a heart rate worth recording for a long time.

Laz went to the next box, the next, the next. If these had once been healing caves, they had failed at their function. These occupants were beyond healing.

Most of them seemed to be small. Many were child-sized. Same size box as Laz’s though, as if they were supposed to grow into them, like oversized hand-me-downs from older siblings—a concept which Laz, as an only child, had never experienced for himself.

Now as he looked out over the dim array of boxes, he knew that this was no hospital. It was more like a graveyard. All these boxes must contain dead bodies.

Why had his cave still functioned? Did these boxes all go dark because the clone inside was dead? Or did the occupants die because the boxes went dark?

Why am I alive? And why hasn’t anyone come to meet me? To yell at me for getting out of my box without permission? It would be nice to get into a brisk argument with some idiotic adult who was castigating him for not obeying rules that Laz had never heard of.

Laz enjoyed arguments in which the opponent was locked into positions whose absurdity made it impossible for them to speak sensibly. Other kids would give up and walk away—or get mad and jab at him. But adults always had a completely unjustified certainty that if they just talked long enough at a younger person, they would prevail.

In this case, Laz would have liked the argument for a completely different reason: It would mean that there was another person present. It would mean he was not alone.

Laz walked back to the open door and stepped halfway through, one foot inside, one outside of the room. He saw controls for the door on the outside, too.

He would have to try the outside buttons. If they did not work and the door closed behind him, then he could decide whether to side step into a reality in which he had not chosen to step outside, or just live with the decision and continue exploring the building.

He pressed one set of buttons and the door closed and reopened. He pressed the other, and bright ceiling lamps flooded the interior of the huge room with light.

It turned out the corridor lights had not been bright at all—in fact, they were as dim as the EXIT lights in a theater. Laz realized that even the lights now illuminating the room were probably not all that bright—his eyes just weren’t accustomed to having light at all.

His impressions of the big room had been correct. By chance he had gone the shortest way from his healing cave to the nearest wall; there had to be upwards of fifty rows in every direction. He could see that there were doors about every thirty meters along the walls, leading somewhere. It wasn’t Laz’s job to find out where, unless it turned out that this corridor led nowhere.

Laz turned off the light. He closed the door. Maybe there was another functioning healing cave inside another room, and maybe he would locate it and find a living human being.

Later. First he needed to find out where everybody was. Who was in control of this operation.

No. First he had to find a drink of water.

In the course of wandering around the corridors, he found two drinking fountains, but the chilling unit wasn’t working in either one, and when he pressed the button, water didn’t flow. It didn’t even dribble out. The water seemed to have been cut off.

But I didn’t dry out in my box, thought Laz. Moisture got to me somehow. My box kept me alive. Something in this place is still working.

The corridors formed a maze—or maybe it was a perfectly consistent pattern that he just didn’t understand. There were doors in other walls, but they didn’t respond to a button press.

Then it dawned on him that there was something else that none of the walls had.

Windows.

Maybe he was underground.

He went to the end of a wide corridor. It butted up against a wall.

To the left and right, though, there were buttons. No doors, no numbers, no labels, just buttons. He pressed one.

The whole floor, from the end wall to about six meters out, rose smoothly. A low wall appeared on the outside edge, enough to keep a rolling cart from falling off. The ceiling parted above him. He went past another floor, with dimly lighted corridors. This time when the ceiling above the elevator platform opened, there was a much brighter light. It was daylight, Laz knew, simply from the quality of the light. Nothing artificial. Sun through glass, that’s what he was seeing.

The floor with his healing cave was two floors below daylight.

The elevator stopped—apparently this was as high as it went. The low barrier wall was gone. Laz stepped out into the sunlit corridor, which quickly led to a large open glass-walled reception area.

There was nobody at the reception desk. Nobody at the doors. Nobody on the furniture.

And not much furniture, either. It was as if all the good pieces had been removed, and only the ones with tatty upholstery were left. Like at an underfunded school.

There had once been electronic equipment at the reception station, but all that remained were sockets of various kinds.

This place screamed, Out of business.

Yet one of those healing caves two floors down had contained a living person. Did you all just forget me?

There were big letters on the glass wall. They were backward—they were sending their message out onto the street. But Laz easily read them, though he had to walk through the large open space for a while before he was sure he had seen all the letters.

From the outside, passersby would have read the word “Vivipartum.” It sounded like a company name. Laz thought through his Latin roots and figured that it might mean something like “born alive.” He had once had “parturition”—birth—as a vocabulary word, and “vivid” clearly was related to life.

And that was his confirmation of what this place was. Not a hospital at all. Not even a retirement home for dying people hoping to be kept alive till there was a cure.

He remembered the articles and essays and op-eds and diatribes and slogans from three or four years ago, when the technology for cloning and fast-growing human bodies had been developed. At that time, cloning was justified solely as a means of supplying organs and limbs for the genetic owner, in case things went badly and a transplant was needed. No more hoping for a liver donor or heart donor, no more matching blood types and using immunosuppressants. All transplant needs were met using organs and limbs that were genetically identical to the transplant recipient.

The clones will never be brought to consciousness, the proponents assured everyone. They will never have legal existence as people. They are not citizens. They are organ and limb banks, with individual proprietors whose DNA had been used to create them.

Meanwhile, religions were in a frenzy over the question of whether clones had souls, whether they were tainted by original sin, whether they were eligible for redemption. They were never alive and could not be resurrected; they were definitely alive and to kill one in order to harvest a vital organ was murder. So many people were sure that their view was the only one a decent person could have.

This was all mildly interesting to Laz as a kid. He remembered that the courts had allowed cloning and harvesting to continue, under the legal theory that clones never achieved consciousness or acted upon their own volition in any way, and were therefore nonpersons in the eyes of the law. Property.

The controversy didn’t die down completely, so the big cloning corporations spun off the cloning operations into a lot of smaller companies with different names. They all pretended to be in another line of work, and most of them actually conducted other businesses.

In this Vivipartum building, all the rows of boxed clones were underground.

Maybe when the owners of the clones stopped making their payments, the life support was cut off and the clones all died. That made sense to Laz. These weren’t people, so nobody cared if they died.

But somebody had kept up payments on Laz’s body, so he lived.

And something else. The clones were never supposed to achieve sentience or volitional behavior. Yet here was Laz walking around, full of memories of a childhood that this body had never lived through. If he was in fact a clone.

He was a clone with a memory.

Had the technology moved forward, without anybody reporting on it? Could they take the memories out of the original owner’s brain and then play them into the brain of the clone? Laz had never heard of such a technology, but then, after the huge brouhaha about cloning in the first place, the companies would keep such a development completely under wraps, because it would reopen the whole person/nonperson debate again, and who knew where the courts would land?

Laz had not been cloned to provide body parts for some older version of Laz. Laz had been given the memories of his life up to age seventeen. Laz was being prepared to be a replacement.

Ridiculous. Why replace somebody who wasn’t dead? If his older original self had died, they could only revive him if they had recorded his memories while he was alive. Laz had no memory of that. If somebody judged a teenager like him to be important enough to record, Laz would not have forgotten it.

If his original self was alive, why would they be prepping Laz to replace him?

Maybe they now put memories into all the clones. Maybe so that they could do a brain transplant, if that was necessary. And it was just random chance that Laz’s clone had survived when so many others downstairs had died.

Maybe I’m not a clone at all. Maybe I’ve read this whole situation wrong.

In the whole time he had been standing in the glass-walled reception area, not a single vehicle had passed by on the street outside.

Laz walked to the window, then to another spot in the glass wall, and he saw that the parking lot wasn’t empty. There were a few cars in it, but they were parked any which way. Like nobody cared. And there were a couple of cars with people in them, but they weren’t moving. Neither the cars nor the people.

There were crash bars on the doors—strictly according to fire code—but Laz was afraid again that once he went through the doors and let them close behind him, he wouldn’t be able to get back in. Besides, he didn’t know if the weather outside was sunny and hot or sunny and cold. He sure wasn’t dressed for cold.

He pushed open the outside door. A blast of air came in. Cold. But not bitterly cold. Colder than Los Angeles. More like San Francisco standing near the water.

Holding one door open, he pulled on the handle of the other. Locked.

He looked for a way to unlock it. If nobody had noticed him so far, he wasn’t going to count on being able to knock on the door and have somebody let him back in. He stepped back into the doorway and looked for a way to unlock the door mechanically. No such.

So he pulled one of the tatty sofas over to the door and awkwardly pushed it out between the two doors, to hold them both open. Surely this would bring some kind of security guy into the reception area.

It didn’t.

Laz went outside and walked toward a car with a guy in it.

A dead guy. A guy who had been dead for a long time. A guy with a smashed-in head. Or a blasted head. There was no gun in the car, though, if he had killed himself.