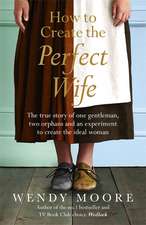

Wedlock: How Georgian Britain's Worst Husband Met His Match

Autor Wendy Mooreen Limba Engleză Paperback – 26 dec 2009

WEDLOCK is the remarkable story of the Countess of Strathmore and her marriage to Andrew Robinson Stoney. Mary Eleanor Bowes was one of Britain's richest young heiresses. She married the Count of Strathmore who died young, and pregnant with her lover's child, Mary became engaged to George Gray. Then in swooped Andrew Robinson Stoney. Mary was bowled over and married him within the week.

But nothing was as it seemed. Stoney was broke, and his pursuit of the wealthy Countess a calculated ploy. Once married to Mary, he embarked on years of ill treatment, seizing her lands, beating her, terrorising servants, introducing prostitutes to the family home, kidnapping his own sister. But finally after many years, a servant helped Mary to escape. She began a high-profile divorce case that was the scandal of the day and was successful. But then Andrew kidnapped her and undertook a week-long rampage of terror and cruelty until the law finally caught up with him.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 83.38 lei 3-5 săpt. | +14.74 lei 7-13 zile |

| Orion Publishing Group – 26 dec 2009 | 83.38 lei 3-5 săpt. | +14.74 lei 7-13 zile |

| BROADWAY BOOKS – 31 ian 2010 | 116.45 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 83.38 lei

Nou

15.95€ • 16.66$ • 13.20£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Livrare express 01-07 martie pentru 24.73 lei

Specificații

ISBN-10: 0753828251

Pagini: 512

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 40 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Orion Publishing Group

Recenzii

—Caroline Weber, author of Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution

“What a story! A beautiful, wealthy countess, accustomed to a life of cosseted privilege, is deceived by an almost impossibly dastardly scoundrel. In Wendy Moore's skillful hands, the decadent and complex world of eighteenth century England, from the broad lawns and exquisite gardens of vast country estates to the Dickensian murk of the London courts, springs to life in all of its gorgeous detail. A darkly fascinating tale of seduction and domestic abuse.”

—Nancy Goldstone, author of Four Queens: The Provencal Sisters Who Ruled Europe

“Drawing on her extensive research and sure grasp of the period, Wendy Moore has produced a gem. Her compelling account of the feisty Countess of Strathmore is a beautifully written page-turner of a book.”

—Julia Fox, author of Jane Boleyn: The True Story of the Infamous Lady Rochford

“A gripping story, brilliantly told. The tragic history of Mary, Countess of Strathmore, is more than a cautionary tale. Mary is a true heroine: a survivor and a fighter against a brutish husband and an uncaring society. Wendy Moore succeeds admirably in describing a marriage that was forged in hell but lived on earth.”

—Amanda Foreman, author of Georgiana: Duchess of Devonshire

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

London, January 13, 1777

Settling down to read his newspaper by the candlelight illuminating the dining room of the Adelphi Tavern, John Hull anticipated a quiet evening. Having opened five years earlier, as an integral part of the vast Adelphi development designed by the Adam brothers on the north bank of the Thames, the Adelphi Tavern and Coffee House had established a reputation for its fine dinners and genteel company. Many an office worker like Hull, a clerk at the government’s Salt Office, sought refuge from the clamor of the nearby Strand in the tavern’s upper- floor dining room with its elegant ceiling panels depicting Pan and Bacchus in pastel shades. On a Monday evening in January, with the day’s work behind him, Hull could expect to read his paper undisturbed.

At first, when he heard the two loud bangs, at about 7 p.m., Hull assumed they were caused by a door slamming downstairs. A few minutes later, there was no mistaking the sound of clashing swords. Throwing aside his newspaper, Hull ran down the stairs and tried to open the door to the ground- floor parlor. Finding it locked, and growing increasingly alarmed at the violent clatter from within, he shouted for waiters to help him force the door. Finally bursting into the unlit room, Hull could dimly make out two figures fencing furiously in the dark. Reckless as to his own safety, the clerk grabbed the sword arm of the nearest man, thrust himself between the two duelists, and insisted that they lay down their swords. Even so it was several more minutes of struggle before he could persuade the first man to yield his weapon.

It was not a moment too soon. The man who reluctantly surrendered his sword now fell swooning to the floor, and in the light of candles brought by servants, a large blood stain could be seen seeping across his waistcoat. A cursory examination convinced Hull that the man was gravely injured. “I think there were three wounds in his right breast, and one upon his sword arm,” he would later attest. The second duelist, although less seriously wounded, was bleeding from a gash to his thigh. With no time to be lost, servants were dispatched into the cold night air to summon medical aid. They returned with a physician named John Scott, who ran a dispensary from his house nearby, and a surgeon, one Jessé Foot, who lived in a neighboring street. Both concurred with Hull’s amateur opinion, agreeing that the collapsed man had suffered a serious stab wound when his opponent’s sword had run through his chest from right to left–presumably on account of the fencers’ standing sideways–as well as a smaller cut to his abdomen and a scratch on his sword arm.

Disheveled and deathly pale, his shirt and waistcoat opened to bare his chest, the patient sprawled in a chair as the medical men tried to revive him with smelling salts, water, and wine and to staunch the bleeding by applying a poultice. What ever benefit the pair may have bestowed by this eminently sensible first aid was almost certainly reversed when they cut open a vein in their patient’s arm to let blood, the customary treatment for almost every ailment. Unsurprisingly, given the weakening effect of this further loss of blood, no sooner had the swordsman revived than he fainted twice more. It was with some justification, therefore, that the two medics pronounced their patient’s injuries might well prove fatal. The discovery of two discarded pistols, still warm from having been fired, suggested that the outcome could easily have been even more decisive. With his life declared to be hanging by a thread, the fading duelist now urged his erstwhile adversary to flee the tavern–taking pains to insist that he had acquitted himself honorably–and even offered his own carriage for the getaway.

This was sound advice, for duels had been repeatedly banned by law since the custom had been imported from continental Europe to Britain in the early seventeenth century. Anyone participating in such a trial of combat risked being charged with murder, and subsequently hanged, should the opponent die, while those who took the role of seconds, whose job it was to ensure fair play, could be charged as accomplices to murder. Yet such legal deterrents had done little to discourage reckless gallants bent on settling disputes of honor. Far from withering under threat of prosecution, dueling had not only endured but flourished spectacularly in the eighteenth century. During the reign of George III, from 1760 to 1820, no fewer than 172 duels would be fought, leaving sixty- nine dead and ninety- six wounded. The gradual replacement of swords by pistols in the later eighteenth century inevitably put the participants at greater risk of fatal injury. John Wilkes, the radical politician, survived a duel in 1763 only because his opponent’s bullet was deflected by a coat button. As the fashion for settling scores by combat grew, so too the perverse rules of etiquette surrounding dueling became more convoluted and rule books, such as the “Twenty- six Commandments,” published in Ireland in 1777, were produced in an attempt to guide combatants through the ritualistic maze.

Yet despite the legal prohibition, the deadly game was widely tolerated. During George III’s long reign, only eigh teen cases were ever brought to trial; just seven participants were found guilty of manslaughter and three of murder, and only two suffered execution. This lax approach by authority was scarcely surprising, given that duels were fought primarily by the titled, the rich, and the powerful, including two prime ministers–William Petty Shelburne and William Pitt the Younger–and a leader of the opposition, Charles James Fox. Public opinion largely condoned the practice, which was frequently glorified in romantic fiction, too.

Yet despite the very real risk that he might swing on the gallows on account of the condition of his opponent, the second duelist in the Adelphi Tavern that night declined the offer of escape. Certainly, the wound to his thigh meant that he was in little shape to run. But it was also the case that he was too well known to hide for long.

As the parlor filled with friends and onlookers, including the two seconds belatedly arriving on the scene, many recognized the fashionably attired figure of the apparent victor of the contest as the Reverend Henry Bate. Although attempted murder was hardly compatible with his vows to the church, the 31- year- old parson had already established something of a reputation for bravado. Educated at Oxford, although he left without taking a degree, Bate had initially joined the army, where he acquired valuable skills in combat. But he promptly swapped his military uniform for a clerical gown when his father died, and the young Bate succeeded to his position as rector of the country parish of North Fambridge in Essex, in the south of En gland. Before long he had added the curacy of Hendon, a sleepy hamlet north of London, to his ecclesiastical duties. Comfortably well- off but socially ambitious, Bate’s impeccably groomed figure was a more familiar sight in the coffee- houses and theatres of London than in the pulpits of his village churches. Indeed, it was his literary, rather than his religious, works for which Bate was famed.

Friendly with the capital’s theatrical community, Bate had written several farces and comic operas that had met with moderate acclaim, but he employed his pen to much greater effect as editor of the Morning Post. Set up in 1772 as a rival to the Morning Chronicle, the Post had developed a pioneering combative style that contrasted sharply with the dull and pompous approach of its competitors. Since his appointment as editor two years previously, Bate had consolidated his newspaper’s reputation for fearlessly exposing scandal in public and private life, boosting circulation as a result. While taking full advantage of the recent hard- won freedom for journalists to report debates in Parliament, the Post took equal liberties in revealing details of the intrigues and excesses of Georgian society’s rich and famous, the so- called bon ton. Although strategically placed dashes supposedly obscured the names of the miscreants, the identities of well- known celebrities of their day, such as “Lord D–re” and “Lady J–sey,” were easily guessed by their friends and enemies over the breakfast table.

At a time when the importance of the press in a constitutional democracy was becoming increasingly recognized–as was its potential for abusing that freedom–Bate stood out as the most notorious editor of all. Flamboyant and domineering–some would say bullying– Bate had recently sounded the death knell of a copycat rival of the Post in characteristic style, by leading a noisy pro cession of drummers and trumpeters marching along Piccadilly. Horace Walpole, the remorseless gossip, was appalled at the scene that he watched from his window and described to a friend: “A solemn and expensive masquerade exhibited by a clergyman in defence of daily scandal against women of the first rank, in the midst of a civil war!” he blustered. Samuel Johnson, as a fellow hack, at least gave Bate credit for his “courage” as a journalist, if not for his merit. This was something of a backhanded compliment, however, since as Johnson explained: “We have more respect for a man who robs boldly on the highway, than for a fellow who jumps out of a ditch, and knocks you down behind your back.”

Acclaimed then, if not universally admired, as a vigorous defender of press freedom, Bate had also established a reputation for his physical prowess. A well- publicized disagreement some four years previously at Vauxhall, the pop u lar plea sure gardens on the south bank of the Thames, had left nobody in doubt of his courage. Leaping to the defense of an actress friend who was being taunted by four uncouth revelers, Bate had accepted a challenge by one of the party to a duel the following day. When the challenger substituted a professional boxer of Herculean proportions, Bate gamely stripped to the waist and squared up. Although much the smaller of the two pugilists, the parson proceeded to pummel the boxer into submission within fifteen minutes, mashing his face “into a jelly” without suffering a single significant blow himself. The episode, which was naturally reported fully in the Morning Post, earned Bate the nickname “the Fighting Parson.” Having established his credentials for both bravery and combat skills, the Reverend Bate was evidently not a man to pick an argument with. Oddly this had not deterred his opponent at the Adelphi.

A relative newcomer to London society, though he had acquired some notoriety in certain circles, the defeated duelist was seemingly a stranger to everyone in the tiny parlor with the exception of his opponent and his tardy second. Although he was now sprawled in a chair under the ministrations of his medical attendants, it was plain that the man was slenderly built and uncommonly tall by eighteenth- century standards. The surgeon Foot, meeting him here for the first time, would later estimate his height at more than five feet ten inches–a commanding five inches above the average male. Despite a prominent hooked nose, his face was strikingly handsome, with thin but sensuous lips and small, piercing eyes under thick dark eyebrows. His obvious authority and bearing betrayed his rank as an officer in the King’s Army, while his melodic brogue revealed his Anglo- Irish descent. And for all his life- threatening injuries, he exuded a charisma that held the entire room in thrall. His name was gleaned by the gathered party to be Captain Andrew Robinson Stoney. And it was he, it now emerged, who had provoked the duel.

With the identity of the duelists established, details of the circumstances leading to their fateful meeting quickly unfolded and were subsequently confirmed in a report of events agreed between the combatants for release to the press. In providing this statement, attributing neither guilt nor blame, the duelists were complying with contemporary rules of dueling conduct. But as their version of events made plain, most of the circumstances surrounding the Adelphi duel had flouted all the accepted principles of dueling behavior. Meeting at night rather than in the cold light of day (traditionally at dawn), staging their duel inside a busy city venue rather than a remote location outdoors, and fighting without their seconds (who should have been present to promote reconciliation) were all strictly contrary to the rules. Yet the pretext for their fight to the death was entirely typical of duels that had been conducted since medieval knights had first engaged in the lists. The honor of a woman, it emerged, was at the crux of the dispute.

In the perverse code of honor that governed dueling, any form of insult to a woman was to be regarded by a man whose protection she enjoyed as the gravest possible outrage. According to the “Twenty- six Commandments,” for example, such an insult should be treated as “by one degree a greater offence than if given to the gentleman personally.” So while women were by convention almost always absent from duels, shielded from the horror of bloodshed and gore, their reputation or well- being was frequently at the very core of the ritual. Indeed, for some women, it might be said, the prospect of being fought over by two hot- blooded rivals could be so intoxicating that they sometimes encouraged duels even if they later regretted the consequences.

There was no doubt, in the case of the duel at the Adelphi, that the reputation of the woman in question had been grossly impugned. Since early December 1776, readers of Bate’s Morning Post had read with mounting interest reports of the amorous exploits of the recently widowed Countess of Strathmore. Despite having only just shed her mourning costume, the young countess had been spotted in her carriage riding through St. James’s Park engaged in a passionate argument with a military man whom the Post had named as Captain Stoney. Simultaneously fueling his readers’ titillation and moral outrage, the newspaper’s anonymous correspondent had speculated on whether the wealthy widow would bestow her favors on the Irish soldier or on a rival suitor, a Scottish entrepreneur called George Gray, who had recently brought home a small fortune from India. Even more scandalously, the Post suggested, the countess might find herself in the “arms of her F–n,” a thinly disguised reference to her own footman. Less than two weeks later, readers spluttered into their morning coffee as the Post divulged on successive mornings, first that the countess had broken with her “longfavoured- paramour,” presumably Gray, and next that she was planning to elope with him abroad.

If the readers of the Post harbored any doubts as to the impropriety of the countess’s conduct, these were briskly swept aside by a concurrent series of articles, in the form of a curious exchange of letters, that alternately condemned and defended her behavior. Written under a variety of pseudonyms, one side accused the countess of betraying the memory of her late husband, the Earl of Strathmore, whose death she was said to have greeted with “cold indifference,” and of forsaking her five young children in her blatant exploits with her various suitors. Equally forthright in her defense, the other side insisted that the young widow suffered “heart- felt sorrow” in her bereavement.

Whether or not the countess, in exasperation at the intrusion of the press into her private affairs, had provoked the duel to defend her honor was a matter of conjecture. One member of her house hold in London’s fashionable Grosvenor Square would later claim that the countess had declared that “the man who would call upon the Editor of that Paper, and revenge her cause upon him, should have both her hand and her heart.” By the middle of January 1777, the Irish army officer Stoney had stepped forward and taken it upon himself to act–in Bate’s words–as the “Countess of Strathmore’s champion.”

Given the vindictive nature of the articles naming both the countess and himself, Stoney had initially written to Bate demanding to know the identity of the writers. Somewhat surprisingly, Bate responded by insisting he did not know. In truth, this was not unlikely. The lurid public interest in the sexual misdemeanors of Georgian celebrities had spawned a highly organized industry in gossip- mongering. Certain newspapers even provided secret post boxes so that those with salacious information could anonymously submit their claims directly to the printers, while newspaper editors frequently had neither sight nor supervision of such material prior to publication. Although publishing inflammatory accusations, without the least effort made to check their veracity, raised the serious prospect of being sued for libel, publishers often gauged that the boost in their circulation figures justified the risk.

Bate’s protestations of ignorance, coupled with his profuse apologies, did little to mollify Stoney, who took the somewhat progressive view that an editor should assume responsibility for the material published in his newspaper. Bate had therefore little option but to agree to a meeting with the irate soldier. According to their record of events, this meeting took place on the evening of Friday, January 10, in the Turk’s Head Coffee- house in the Strand. Here, in the convivial atmosphere of the fuggy coffee- house, Bate had managed to convince Stoney that he had been innocent of any involvement in the articles and promised to ensure that no more insults would appear. And so when Stoney opened the Post the following morning to read yet further revelations about the countess’s love life, he was apoplectic. The latest article, which reported that “the Countess of Grosvenor- Square, is frequently made happy by the visits (tho’ at different periods) of the bonny, tho’ almost expended Scot, and the Irish widower,” seemed almost calculated to incense him. Immediately, Stoney dashed off another letter to Bate demanding his right “to vindicate the dignity of a Gentleman” by seeking satisfaction in the traditional manner. He concluded by naming an old army friend, Captain Perkins Magra, as his second who would arrange events.

Still Bate blustered and equivocated. In the flurry of letters that flew back and forth across the city that weekend, all faithfully reproduced in the jointly agreed record, the men’s accusations and counter- accusations grew more and more heated. When finally he was denounced as a “coward and a scoundrel,” Bate had little alternative but to accept Stoney’s challenge. On Monday, January 13, therefore, Bate had consulted his own old army buddy, the rather dubious Captain John Donellan, who had recently been dismissed from ser vice in India. Already accused of various financial irregularities while serving with the East India Company, Donellan would eventually be hanged for poisoning his wife’s brother to get his hands on her family’s riches. Agreeing to stand as Bate’s second, Donellan had lent the parson his sword, which Bate hid under his greatcoat. That afternoon Bate had sent Stoney a final letter, which ended resignedly: “I find myself compelled to go so far armed, in the event at least, as to be able to defend myself, and since nothing can move you from your sanguinary purposes–as you seemed resolved, that either my life or my gown shall be the sacrifice of your groundless revenge–in the name of God pursue it!”

Having dined out on Monday afternoon, Bate set off apprehensively just after 6 p.m., his friend’s sword held ready beneath his coat, to walk the dimly lit streets to his home, one of the new Adelphi houses in Robert Street. Turning off the bustling Strand onto Adam

Street, he was passing the doorway of the Adelphi Tavern when the towering figure of Stoney loomed toward him, seized him by the shoulder, and forced him inside. Still protesting that he did not wish to come to blows, “the Fighting Parson” had reluctantly accompanied the Irishman into the ground- floor parlor, where Stoney once more demanded he reveal the names of the writers of the offending articles. On Bate’s insistence that he did not know, the soldier declared: “Then, Sir, you must give me immediate satisfaction!”

In the sputtering light of candles, Stoney’s valet brought in a case containing a pair of pistols that had been purchased that day from the shop of Robert Wogdon, London’s most celebrated gunsmith whose exquisitely crafted dueling pistols were renowned for their lightness, speed, and–above all–deadly accuracy. A duel being now unavoidable, and the death of one or both duelists probable, both men sent word to summon their seconds. Stoney dispatched his valet to locate Captain Magra, while Bate sent a hurried note to find his friend Donellan. When neither of these fellows had appeared after some considerable delay, and with Bate becoming increasingly anxious to escape, Stoney abruptly locked the parlor door, stuffed the keyhole with paper, and placed a screen in front of it. Opening the case of Wogdon’s pistols, he had ordered Bate to choose his weapon. When the parson refused first fire, Stoney immediately snatched up a pistol and took aim. But for all his military training, the proximity of his target, and the superiority of Wogdon’s guns, his bullet had merely pierced the parson’s hat and cracked the mirror behind. In returning fire, according to dueling procedure, Bate’s aim was equally askew–or equally well- judged–for his bullet apparently ripped through Stoney’s coat and waistcoat without so much as grazing his opponent’s skin.

Still thirsty for blood, Stoney insisted that they now draw swords. Only when blood had been spilled, according to dueling law, could honor be said to have been satisfied. As Stoney charged toward him with his sword outstretched, Bate deflected the weapon and speared his opponent right through the chest. So fierce was the ensuing combat in the expiring candlelight that Bate’s borrowed sword was bent almost in half, at which point Stoney decently allowed him to straighten it. And although he was bleeding profusely and was severely weakened by his injuries, Stoney insisted on continuing the fight until the door finally burst open and Hull tumbled into the room. Quickly taking in the scene dimly reflected in the broken mirror, Hull and the other rescuers had little doubt that they had only just prevented a catastrophe.

Later publishing his own version of what he described as the “late affair of honour” in The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, Hull had declared his surprise, given the darkness of the room and the ferocity of the fencing, that “one of the combatants were not absolutely killed on the spot.” It was a sentiment with which the two medical men, Foot and Scott, readily agreed. In a joint statement published in the same newspaper, in which they described their patients’ injuries in detail, the pair attested that Stoney’s chest wound had “bled very considerably.” They concluded “we have every reason to believe, that the rencontre must have determined fatally, had not the interposition of the gentlemen who broke into the room put an end to it.” Indeed, as Foot helped the ailing Stoney into his carriage and rode with him back to the officer’s apartment at St. James’s Coffee House in nearby St. James’s Street, his professional concern was so great that he insisted on stopping en route in Pall Mall, at the house of the celebrated surgeon Sir Caesar Hawkins, for further medical assistance. One of the most popular surgeons in London, numbering George III among his patients, the elderly Hawkins visited Stoney in his rooms two hours later. Although he did not personally examine the wounds, merely checking the patient as he languished in bed, Hawkins would later add his own testimony as to the severity of the duelist’s injuries. Four respectable witnesses, therefore, all testified to the life- threatening nature of Stoney’s wounds. It was scarcely surprising, then, given the captain’s plight, that the object of his devil- may- care venture should visit her hero the very next day.

From the Hardcover edition.