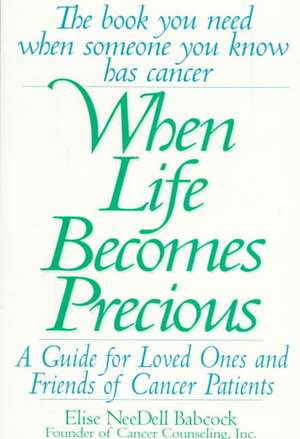

When Life Becomes Precious: The Essential Guide for Patients, Loved Ones, and Friends of Those Facing Serious Illnesses

Autor Elise NeeDell Babcock, Babcocken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 1996

You want to be as supportive as possible. But how?

Elise NeeDell Babcock has devoted her life to answering this question and now puts her twenty-three years of experience as a counselor into this immensely useful guide. When Life Becomes Precious contains hundreds of tips for helping patients, primary caregivers, co-workers, and family members, including:

What to say (and not to say) to someone when you first find out they have cancer

• How to be supportive without being intrusive

• How to build a winning health-care team

• How to handle holidays, birthdays, and anniversaries

• How to explain the disease to children

• Which gifts and gestures can do the most good

From techniques for handling anger and anxiety, to uplifting success stories, to a comprehensive resource section, here is the information and inspiration you need to help those you love and to make each day--each moment--more precious.

When Life Becomes Precious will be the first book to:

• Offer tips on ways to help patients, caregivers and co-workers

• Provide a long and diverse list of gifts that are appropriate to give to families that are living with cancer

• Offers reasons why fear makes people shy away from discussing cancer and techniques on how to overcome that fear

• Present the things that families do that doctors like and dislike

When Life Becomes Precious will teach readers to assess and put into perspective, their own feelings about the disease so that they can truly help those who are afflicted with it. The use of cartoons, anecdotes and personal stories will set an upbeat and positive tone. Readers will come away fully prepared to deal with the realities of cancer.

Preț: 118.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 177

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.58€ • 23.49$ • 18.64£

22.58€ • 23.49$ • 18.64£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553378696

ISBN-10: 0553378694

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 153 x 227 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553378694

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 153 x 227 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Bantam

Extras

Kicking my office door closed, I waited, listening to my father's voice on the phone, the voice of a frightened and broken man, a sound I'd never heard before from him. Although he hadn't told me anything disturbing yet, I was terrified. Perhaps that's what happens when we go into shock. The sound of a frightened voice alerts the mind, clearing it, leaving in it only room for what is to come. Hundreds of miles away, I could hear my father calculating, regrouping, and then he spoke. "Your mother has lung cancer."

"But," I yelled, "she just told me she stopped smoking," as though that had anything to do with it. Even though I was president of a cancer agency, I was reacting as any daughter might _ reaching for anything to make his words disappear.

"We need your help. We need a second opinion." He didn't tell me then, nor did I find out until years later, but the first doctor had said her cancer was inoperable. There was no hope. My father asked me for the name of a surgeon. I started my list. He wanted books. I imagined packing them. By the end of the call, I was afraid I would lose not only my mother but also my father. They were so mingled, so entwined, each thriving on the other's identity, each filling a place the other couldn't. And after nineteen years of working with cancer patients and their families, I knew his health was as much at risk as hers.

By 1993, I'd seen so many loved ones like him. I'd talked to them, counseled them, comforted them, and yet I did not know what to say to him. Cancer had now walked into my parents' home, the home I grew up in. It had sat on the couch, crossed its arms, announced it was staying. And although I was no stranger to this intruder, since it had entered the homes of others I loved, I found it impossible to be objective when it was sitting on my couch, in my living room.

For me, involvement with the disease started in 1974, when only families were allowed to visit cancer patients. I had to sneak into the hospital to see my teenage friend Jimmy when he was first diagnosed. After that visit, I was to see him only one more time. Together, we rode around the streets of our small New Jersey town, reminiscing, planning, scheduling the dates for a visit that Jimmy would never make, a future he would never see.

The night before he died, he told a mutual friend, "Give Elise a message, tell her I said, 'Thank you.'" I'm still not sure why he said that. I suppose he knew his words would steer me in the right direction. Jimmy knew me all too well. Two months later, I was volunteering at John Runnels Hospital, in the cancer wing.

By 1981, I'd read everything I could about counseling and cancer. I found out a lot about counseling and little about the emotional aspects of cancer. I worked in nonprofit and for-profit health care agencies. I trailed after my cousin's wife, Dr. Elaine Needell, a psychiatrist at Miami Medical School. For five more years, I sat in Baylor College of Medicine's weekly cancer conferences, also taught by a psychiatrist. I watched intently as these professors interviewed cancer patients and then discussed how best to help them. I met with experts, including Dr. Jimmie Holland, chief of psychiatry at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, and Dr. Carl Simonton, author of Getting Well Again. I went to conferences with speakers such as Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. I wrote graduate papers on the psychological impact of the disease.

In 1982, with the help of many people, I started Cancer Counseling in Houston. It was the first agency in the United States to provide free professional counseling to cancer patients and their families during any stage of the disease. Well-known psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers quickly joined the staff. Fourteen of the original fifteen therapists are still with us today. In 1986, one of the staff members, Dr. Norman Decker, and I started the country's first groups for couples coping with cancer. During weekly ninety-minute sessions, six couples came together to talk about living and dying with cancer. These groups, which ran for as long as eighteen months, would change not only the members' lives but Norm's and mine as well.

By 1993, I was president of a cancer agency working primarily with couples coping with cancer. Although what I learned from these couples would help me later, it was of little help that day my father called. So I did what came easy. I found resources. I helped schedule my mother's first visit to Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City within hours of my father's call. It was a fast-growing tumor. If it reached outside the lung, they wouldn't even treat her except to keep her comfortable. I'd seen comfortable many times. I wanted so much more.

Memorial Day weekend. My husband, Jack, and I found my mother in a standard blue hospital room at the end of a long sterile hallway. I lowered myself into an orange plastic chair, the kind that sticks to you in the summer. My parents squeezed themselves together on the raised metal bed, and Jack leaned against the window. That night before surgery, we protected each other with laughter and stories and NBA play-off predictions.

The next morning, I arrived shortly after six, just in time to see my father looking worse than my mother. A crisply dressed, stern-looking, and eventually embarrassed orderly announced himself at the door, and then sharply said to my father, "Are you ready to go now?"

As the orderly wheeled my mother down a long white corridor, I turned to my father and said, "Did you know you can go part of the way?" He shoved on his slippers and was off without a word. I watched as her fingers reached up from the gurney and wrapped themselves around his. When he returned, he whispered, "That was the hardest thing I've ever done." What I wondered was whether it was the last time her outstretched hand would ever reach for his.

Downstairs, more sticky built-in couches awaited us, symmetrically arranged around a wide-open room whose large windows faced a concrete wall and a huge willow tree. There we camped out, steps away from the gift shop filled with the right cards, the perfect words, fresh flowers, and books that were supposed to bring comfort. But for those of us waiting, there was no comfort. Suddenly it occurred to me that all the books I had recommended to clients, most of which I had given to my father, didn't tell families what they needed most. I needed an objective voice, any voice but my own, one whose words would guide me, would tell me what to say to him. My father needed the stories of others who had been where he was now, people who could give him hope, show him the way. As I returned to our stakeout, empty-handed, I vowed to write that book.

We drank too much coffee, ate very little, and said even less. We took turns watching the hallway, waiting. Finally, I reached over, turning my father's wrist, searching for his watch. My dad nodded, only glancing up for the minute it took him to meet my eyes. He went back to reading and rereading the same pages of the Times.

Where was the nurse? Where was my mother? How would my father survive if the biopsy showed more cancer? What was taking so long?

A lanky girl with long, stringy brown hair and squinty eyes swept in. It had to be her, in that starched white uniform with a paper curled like a college degree in her left hand. Her eyes darted about, deciding where to start. There were twenty or so people now seated, desperately waiting, reminding me of a train station scene from Schindler's List, except that it was this nurse who was about to announce who would live and who would die.

She quickly selected an elegant-looking woman in a bright yellow designer suit accentuated by a sparkling gold cat pin. A middle-aged handsome younger man, with a bright green jacket and polo shirt, extended his arm across her shoulder. His knuckles whitened as the nurse headed toward him. The nurse leaned in, nodding her head as she unraveled the reports and started flipping through them.

The woman began wiping tears from her eyes. Patting her back, the man guided her off the couch. They held on to each other as they left the room. Was it relief or devastation? I couldn't tell.

Then I heard her, before I realized she was standing in front of us --Sharon, that's what her name tag said. "They have sent the tissue in for biopsy." Her detached professionalism revealed not a hint of compassion. She scrambled away.

I raced after her. "But that doesn't tell us anything," I said, anger, exhaustion, and fear creeping into my voice. "How long ago was that?" I asked. She looked down, bothered. "About an hour ago," she answered, clearly annoyed. As we had been one of Sharon's last stops, it was now three hours later. My mother, for all I knew, could have already died, or maybe she was in recovery, the surgeons having decided not to operate, not to save her, because the biopsy had shown that the cancer had spread beyond the lung.

"I need," I almost whispered to her, "to know if they have started the major surgery yet. The biopsy was the determining factor. They said it would take forty-five minutes; that was three hours ago. Please go back there and find out." I pointed to some place, some place that seemed so far away, a place I could not go. Sharon reached out, touching my arm, and with compassion filling her eyes, she looked at me.

"I'll be right back."

She returned in minutes. "They have started to remove the lung," she said. Two hours later, a young bulky resident entered the room.

"That's one of the team," my father said. By now, Jack had joined us. The three of us stood up. While looking exhausted, but nevertheless smiling, the resident announced, "She's in recovery. Everything went well. There's no other sign of the cancer."

In July, we were relieved when my mother ventured back to work and then to the golf course, playing six holes, walking twelve. It was a sign, wasn't it? She was returning to her old life, reclaiming her territory. I should have known better. Neither patients nor their families return to their old lives. But they do create new lives, often richer and more fulfilling.

Someday it would hit us all, what had happened. For now, we could only navigate the uncharted waters that lay ahead, waters that each of us had to master on our own.

By Christmas, Jack reminded me of my vow "to write that book." But I was working on a novel and ignored his constant pleas. Over lunch a few weeks later, Larry Thompson, past chairman of Cancer Counseling and the brother of author Thommy Thompson, said, "It's time to write that book."

"But I love the novel I'm working on," I protested. Larry, Jack, and Jimmy knew me all too well. Without flinching, Larry continued, "Writing the book will help others, and it's what you need to do next."

And he knew I would do exactly that. So I began the book I had vowed to write while in that waiting room. I called old friends, colleagues, patients, and clients. I interviewed hundreds of people, asking them what they wanted to teach others, what they themselves wanted to know, what they wished someone had told them. I began leading a support group for M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, as I was drawn back into the work I love so much.

July 1996. My mother walked into my room after a grueling flight to Houston. There she stood, silent, amazed, captivated, staring at my fifteen-month-old daughter, Megan (Lexi) Alexandra, who was doing her rendition of a dance --wiggle, clap, squat, and sway --as she stood looking up at the television, pointing toward the screen and nodding her head as though she understood every word of "Barney's song." A knowing glance passed between my mother and me, an understanding and awe at the paths we had traveled. Lexi had arrived only after many unsuccessful pregnancies, and my mother's surgical pain was finally subsiding after three very difficult years. Is life more fulfilling? Do we appreciate it more than those who have not been here? I can't tell you that. But what I can tell you is that the love I experience for my family is beyond any I experienced before 1993. And if love is what defines life, then yes, for me, life is no longer an endless trail of guaranteed time; it is a sacred path, lined with scenes like these.

I hope this book gives you a guide, a map, that you can turn to throughout your journey. I am also hoping that by the end of this book, you appreciate life more fully, and that you appreciate yourself and the role you have taken on, whether you are a health care provider, a patient, a teacher, a student, a co-worker, a loved one, or a friend. For you have embarked on a journey like no other. Although some of your experiences will be unique, different from anyone else's, many will be similar to those of everyone else who has traveled through this world. Whether you are seventeen or sixty-seven, you will have hopes and dreams and fears and obstacles.

Those of us who have overcome the obstacles will try to show you how you can do the same, how doing so can even be empowering. As you reach into this new world, my last hope is that this book will strengthen who you already are, in sharing your love and your spirit while living with cancer, the moments of your life will become more meaningful, more precious.

If you are a patient and you are reading this book, it will help you immensely. Chapter one includes reactions you too may experience. Chapter two will give you insights into the complex reasons people who care about you may not be able to support you. Chapters three, four, and six will help you as you reach out to support your primary caregiver, loved ones and friends. The chapters on talking to children, building your health care team, holidays, and giving without giving out each give practical ways to navigate your way through the journey that lies ahead. Finally, there is a chapter with 52 gift ideas. Your loved ones need to how they can help you. Sharing these ideas with them gives them practical, concrete ways to support you. My hopes are that the more you communicate with each other, the more support and love you will all receive.

"But," I yelled, "she just told me she stopped smoking," as though that had anything to do with it. Even though I was president of a cancer agency, I was reacting as any daughter might _ reaching for anything to make his words disappear.

"We need your help. We need a second opinion." He didn't tell me then, nor did I find out until years later, but the first doctor had said her cancer was inoperable. There was no hope. My father asked me for the name of a surgeon. I started my list. He wanted books. I imagined packing them. By the end of the call, I was afraid I would lose not only my mother but also my father. They were so mingled, so entwined, each thriving on the other's identity, each filling a place the other couldn't. And after nineteen years of working with cancer patients and their families, I knew his health was as much at risk as hers.

By 1993, I'd seen so many loved ones like him. I'd talked to them, counseled them, comforted them, and yet I did not know what to say to him. Cancer had now walked into my parents' home, the home I grew up in. It had sat on the couch, crossed its arms, announced it was staying. And although I was no stranger to this intruder, since it had entered the homes of others I loved, I found it impossible to be objective when it was sitting on my couch, in my living room.

For me, involvement with the disease started in 1974, when only families were allowed to visit cancer patients. I had to sneak into the hospital to see my teenage friend Jimmy when he was first diagnosed. After that visit, I was to see him only one more time. Together, we rode around the streets of our small New Jersey town, reminiscing, planning, scheduling the dates for a visit that Jimmy would never make, a future he would never see.

The night before he died, he told a mutual friend, "Give Elise a message, tell her I said, 'Thank you.'" I'm still not sure why he said that. I suppose he knew his words would steer me in the right direction. Jimmy knew me all too well. Two months later, I was volunteering at John Runnels Hospital, in the cancer wing.

By 1981, I'd read everything I could about counseling and cancer. I found out a lot about counseling and little about the emotional aspects of cancer. I worked in nonprofit and for-profit health care agencies. I trailed after my cousin's wife, Dr. Elaine Needell, a psychiatrist at Miami Medical School. For five more years, I sat in Baylor College of Medicine's weekly cancer conferences, also taught by a psychiatrist. I watched intently as these professors interviewed cancer patients and then discussed how best to help them. I met with experts, including Dr. Jimmie Holland, chief of psychiatry at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, and Dr. Carl Simonton, author of Getting Well Again. I went to conferences with speakers such as Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. I wrote graduate papers on the psychological impact of the disease.

In 1982, with the help of many people, I started Cancer Counseling in Houston. It was the first agency in the United States to provide free professional counseling to cancer patients and their families during any stage of the disease. Well-known psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers quickly joined the staff. Fourteen of the original fifteen therapists are still with us today. In 1986, one of the staff members, Dr. Norman Decker, and I started the country's first groups for couples coping with cancer. During weekly ninety-minute sessions, six couples came together to talk about living and dying with cancer. These groups, which ran for as long as eighteen months, would change not only the members' lives but Norm's and mine as well.

By 1993, I was president of a cancer agency working primarily with couples coping with cancer. Although what I learned from these couples would help me later, it was of little help that day my father called. So I did what came easy. I found resources. I helped schedule my mother's first visit to Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City within hours of my father's call. It was a fast-growing tumor. If it reached outside the lung, they wouldn't even treat her except to keep her comfortable. I'd seen comfortable many times. I wanted so much more.

Memorial Day weekend. My husband, Jack, and I found my mother in a standard blue hospital room at the end of a long sterile hallway. I lowered myself into an orange plastic chair, the kind that sticks to you in the summer. My parents squeezed themselves together on the raised metal bed, and Jack leaned against the window. That night before surgery, we protected each other with laughter and stories and NBA play-off predictions.

The next morning, I arrived shortly after six, just in time to see my father looking worse than my mother. A crisply dressed, stern-looking, and eventually embarrassed orderly announced himself at the door, and then sharply said to my father, "Are you ready to go now?"

As the orderly wheeled my mother down a long white corridor, I turned to my father and said, "Did you know you can go part of the way?" He shoved on his slippers and was off without a word. I watched as her fingers reached up from the gurney and wrapped themselves around his. When he returned, he whispered, "That was the hardest thing I've ever done." What I wondered was whether it was the last time her outstretched hand would ever reach for his.

Downstairs, more sticky built-in couches awaited us, symmetrically arranged around a wide-open room whose large windows faced a concrete wall and a huge willow tree. There we camped out, steps away from the gift shop filled with the right cards, the perfect words, fresh flowers, and books that were supposed to bring comfort. But for those of us waiting, there was no comfort. Suddenly it occurred to me that all the books I had recommended to clients, most of which I had given to my father, didn't tell families what they needed most. I needed an objective voice, any voice but my own, one whose words would guide me, would tell me what to say to him. My father needed the stories of others who had been where he was now, people who could give him hope, show him the way. As I returned to our stakeout, empty-handed, I vowed to write that book.

We drank too much coffee, ate very little, and said even less. We took turns watching the hallway, waiting. Finally, I reached over, turning my father's wrist, searching for his watch. My dad nodded, only glancing up for the minute it took him to meet my eyes. He went back to reading and rereading the same pages of the Times.

Where was the nurse? Where was my mother? How would my father survive if the biopsy showed more cancer? What was taking so long?

A lanky girl with long, stringy brown hair and squinty eyes swept in. It had to be her, in that starched white uniform with a paper curled like a college degree in her left hand. Her eyes darted about, deciding where to start. There were twenty or so people now seated, desperately waiting, reminding me of a train station scene from Schindler's List, except that it was this nurse who was about to announce who would live and who would die.

She quickly selected an elegant-looking woman in a bright yellow designer suit accentuated by a sparkling gold cat pin. A middle-aged handsome younger man, with a bright green jacket and polo shirt, extended his arm across her shoulder. His knuckles whitened as the nurse headed toward him. The nurse leaned in, nodding her head as she unraveled the reports and started flipping through them.

The woman began wiping tears from her eyes. Patting her back, the man guided her off the couch. They held on to each other as they left the room. Was it relief or devastation? I couldn't tell.

Then I heard her, before I realized she was standing in front of us --Sharon, that's what her name tag said. "They have sent the tissue in for biopsy." Her detached professionalism revealed not a hint of compassion. She scrambled away.

I raced after her. "But that doesn't tell us anything," I said, anger, exhaustion, and fear creeping into my voice. "How long ago was that?" I asked. She looked down, bothered. "About an hour ago," she answered, clearly annoyed. As we had been one of Sharon's last stops, it was now three hours later. My mother, for all I knew, could have already died, or maybe she was in recovery, the surgeons having decided not to operate, not to save her, because the biopsy had shown that the cancer had spread beyond the lung.

"I need," I almost whispered to her, "to know if they have started the major surgery yet. The biopsy was the determining factor. They said it would take forty-five minutes; that was three hours ago. Please go back there and find out." I pointed to some place, some place that seemed so far away, a place I could not go. Sharon reached out, touching my arm, and with compassion filling her eyes, she looked at me.

"I'll be right back."

She returned in minutes. "They have started to remove the lung," she said. Two hours later, a young bulky resident entered the room.

"That's one of the team," my father said. By now, Jack had joined us. The three of us stood up. While looking exhausted, but nevertheless smiling, the resident announced, "She's in recovery. Everything went well. There's no other sign of the cancer."

In July, we were relieved when my mother ventured back to work and then to the golf course, playing six holes, walking twelve. It was a sign, wasn't it? She was returning to her old life, reclaiming her territory. I should have known better. Neither patients nor their families return to their old lives. But they do create new lives, often richer and more fulfilling.

Someday it would hit us all, what had happened. For now, we could only navigate the uncharted waters that lay ahead, waters that each of us had to master on our own.

By Christmas, Jack reminded me of my vow "to write that book." But I was working on a novel and ignored his constant pleas. Over lunch a few weeks later, Larry Thompson, past chairman of Cancer Counseling and the brother of author Thommy Thompson, said, "It's time to write that book."

"But I love the novel I'm working on," I protested. Larry, Jack, and Jimmy knew me all too well. Without flinching, Larry continued, "Writing the book will help others, and it's what you need to do next."

And he knew I would do exactly that. So I began the book I had vowed to write while in that waiting room. I called old friends, colleagues, patients, and clients. I interviewed hundreds of people, asking them what they wanted to teach others, what they themselves wanted to know, what they wished someone had told them. I began leading a support group for M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, as I was drawn back into the work I love so much.

July 1996. My mother walked into my room after a grueling flight to Houston. There she stood, silent, amazed, captivated, staring at my fifteen-month-old daughter, Megan (Lexi) Alexandra, who was doing her rendition of a dance --wiggle, clap, squat, and sway --as she stood looking up at the television, pointing toward the screen and nodding her head as though she understood every word of "Barney's song." A knowing glance passed between my mother and me, an understanding and awe at the paths we had traveled. Lexi had arrived only after many unsuccessful pregnancies, and my mother's surgical pain was finally subsiding after three very difficult years. Is life more fulfilling? Do we appreciate it more than those who have not been here? I can't tell you that. But what I can tell you is that the love I experience for my family is beyond any I experienced before 1993. And if love is what defines life, then yes, for me, life is no longer an endless trail of guaranteed time; it is a sacred path, lined with scenes like these.

I hope this book gives you a guide, a map, that you can turn to throughout your journey. I am also hoping that by the end of this book, you appreciate life more fully, and that you appreciate yourself and the role you have taken on, whether you are a health care provider, a patient, a teacher, a student, a co-worker, a loved one, or a friend. For you have embarked on a journey like no other. Although some of your experiences will be unique, different from anyone else's, many will be similar to those of everyone else who has traveled through this world. Whether you are seventeen or sixty-seven, you will have hopes and dreams and fears and obstacles.

Those of us who have overcome the obstacles will try to show you how you can do the same, how doing so can even be empowering. As you reach into this new world, my last hope is that this book will strengthen who you already are, in sharing your love and your spirit while living with cancer, the moments of your life will become more meaningful, more precious.

If you are a patient and you are reading this book, it will help you immensely. Chapter one includes reactions you too may experience. Chapter two will give you insights into the complex reasons people who care about you may not be able to support you. Chapters three, four, and six will help you as you reach out to support your primary caregiver, loved ones and friends. The chapters on talking to children, building your health care team, holidays, and giving without giving out each give practical ways to navigate your way through the journey that lies ahead. Finally, there is a chapter with 52 gift ideas. Your loved ones need to how they can help you. Sharing these ideas with them gives them practical, concrete ways to support you. My hopes are that the more you communicate with each other, the more support and love you will all receive.

Recenzii

"When Life Becomes Precious is both practical and powerful; a sensitive, informative handbook and an inspiring guide to helping others who have cancer. I cannot recommend this book highly enough."

--Jack Canfield, co-author of Chicken Soup for the Surviving Soul

"An indispensable guide for the people most often forgotten when cancer strikes: the spouse, caregivers, and friends of the patient."

--Michael Korda, author of Man to Man: Surviving Prostate Cancer

--Jack Canfield, co-author of Chicken Soup for the Surviving Soul

"An indispensable guide for the people most often forgotten when cancer strikes: the spouse, caregivers, and friends of the patient."

--Michael Korda, author of Man to Man: Surviving Prostate Cancer

Descriere

Elise NeeDell Babcock puts her 23 years of experience as a cancer counselor into an immensely useful guide for helping someone living with cancer.

Notă biografică

Elise NeeDell Babcockwas the founder of Cancer Counseling Inc., the first agency of its kind to provide free professional counseling to people coping with cancer during any stage of the disease. She and CCI were honored by M. D. Anderson Cancer Center as partners in the fight against cancer. Elise was a radio co-host for Talk America and lectured across the country at places such as Yale, Stanford, and Northwestern medical schools. She died in 2010.