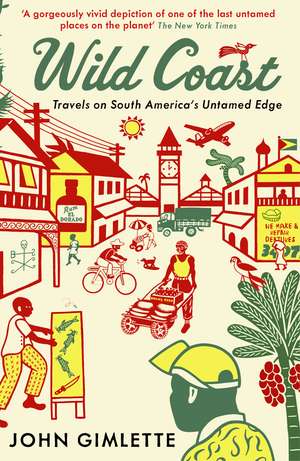

Wild Coast: Travels on South America's Untamed Edge

Autor John Gimletteen Limba Engleză Paperback – 22 feb 2012

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 68.96 lei 3-5 săpt. | +24.55 lei 7-13 zile |

| Profile – 22 feb 2012 | 68.96 lei 3-5 săpt. | +24.55 lei 7-13 zile |

| VINTAGE BOOKS – 31 mai 2012 | 137.94 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 68.96 lei

Preț vechi: 82.39 lei

-16% Nou

13.20€ • 13.81$ • 10.92£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Livrare express 01-07 martie pentru 34.54 lei

Specificații

ISBN-10: 1846682533

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 130 x 196 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: Profile

Colecția Profile Books

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

Notă biografică

John Gimlette has travelled to over sixty countries and has published several books to critical acclaim, including At the Tomb of the Inflatable Pig and is a winner of the Shiva Naipaul Memorial Prize. He contributes regularly to radio and print media including the Guardian, Telegraph, The Times, Independent, Wanderlust and Geographical.

Recenzii

Wild Coast is funny, intelligent, revelatory

A moving, often humorous, and thoroughly enjoyable account that works as both a wartime recollection and travelogue

Great for those interested in Guyanese history, or those looking to explore a South America far from the well-trodden Gringo trail

Gimlette has an eye for a juicy story, a willingness to embark on harebrained journeys and a gleeful way with similes, all of which makes this an entertaining introduction to a forgotten corner of the globe.

Gimlette is an old-school traveller, very British, very cheery. A barrister by trade, the author has an uncanny ability to nail down his characters with a few well-chosen words... Gimlette brings history to life. He artfully merges assiduous research with a storyteller's gift.

A fascinating journey... Gimlette's extensive research has given him access to an intoxicating level of detail.

John Gimlette is sure to secure a name for himself as both a talented writer and a rare traveller who, as documented in the dark chronicles of his book, has visited South America's wild coast and returned apparently unscathed. Fortunately, his writing sculpts an interesting narrative too, and he conveys the region's horror stories with a healthy dose of humour, knowledge, sincerity and poetry...As with all good travel books, the pace of Gimlette's investigations and the idiosyncratic nature of his discoveries, no matter how small, are infectious enough to ensure his account holds its own against these literary greats.

Remarkable... Gimlette is, refreshingly, an unfailing enthusiast... Wild Coast is driven by extraordinary dedication, an insatiable curiosity in everything and an enormous empathy for other people. Gimlette's descriptions of landscapes are often hauntingly beautiful, his sense of humour is engagingly dead-pan... His book is characterised by a thoroughness of research that puts most travel writers to shame...a lucid and lively account of a multi-cultural history... A reminder... of the way in which travel literature can still fulfil its role of bringing to life some of the world's unjustly neglected corners.

Writing that races you through faster than you can turn the pages, a story that transports you to a place you barely knew about before, and all done with a relaxed nonchalance which totally disregards the tough travels John Gimlette's Dolman Award winner clearly involved. Before reading Wild Coast my Guianas knowledge could be summarised as 'don't drink the Kool-Aid, don't end up on Devil's Island, but do go there for an Ariane space launch.' I'm way better informed today.

Descriere

Dolman Travel Book of the Year 2012 Between the Orinoco and the Amazon lies a fabulous forested land, barely explored. Much of Guiana seldom sees sunlight, and new species are often tumbling out of the dark trees. Shunned by the conquistadors, it was left to others to carve into colonies. Guyana, Suriname and Guyane Française are what remain of their contest, and the 400 years of struggle that followed.Now, award-winning author John Gimlette sets off along this coast, gathering up its astonishing story. His journey takes him deep into the jungle, from the hideouts of runaway slaves to penal colonies, outlandish forts, remote Amerindian villages, a 'Little Paris' and a space port. He meets rebels, outlaws and sorcerers; follows the trail of a vicious Georgian revolt, and ponders a love-affair that changed the face of slavery. Here too is Jonestown, where, in 1978, over 900 Americans, members of Reverend Jones's cult, committed suicide. The last traces are almost gone now, as the forest closes in.Beautiful, bizarre and occasionally brutal, this is one of the great forgotten corners of the Earth: the Wild Coast.

Extras

From the Introduction

As far as Amerindians are concerned, the land between the Orinoco and the Amazon has always been Guiana, the ‘Land of Many Waters’. European explorers, however, took a while to appreciate this name. On early French and English maps the region was marked as ‘Equinoctiale’ or ‘Caribana, Land of Twenty-one Tribes’. To the Dutch, on the other hand, this was – for a while – the original ‘New Zealand’. Then they thought of a name which expressed what they felt. It had about it the promise of danger, risk, wealth and perhaps even desire. It was de Wilde Kust, ‘The Wild Coast’.

Certainly nowhere else in South America is quite like it; 900 miles of muddy coastline give way to swamps, thick forest and then – deep inland – ancient flat-topped peaks. It’s never been truly possessed. Along this entire shore, there’s no natural harbour, and beyond the mud the forest begins. It covers over 80 per cent of Guiana, and even now there’s no way through it. Such roads as there are stick mainly to the coast. Without an aeroplane, it takes up to four weeks to get into the interior, and there the problems begin.

With such an abundant canopy, most of Guiana never sees sunlight. Perhaps it’s therefore no surprise that – both in science and history – the story of this land reads like a long, green night. Huge tracts of the interior are only vaguely described, and new species are always tumbling out of the dark. Even some of the more common ones make unnerving companions. Guiana has the biggest ants in the world, and the biggest freshwater fish. There are head-crushing jaguars, strangling snakes, rivers of stingrays and electric eels, and whole clouds of insects all eager to burrow in under the skin. To some this is hell. To others it’s an ecological paradise, a sort of X-rated Garden of Eden.

But it is water, as the Amerindians recognised, that defines Guiana. Through this land run literally thousands of rivers (in Guyana alone there are over 1,500). These aren’t like the little waterways that meander through the Old World, but vast sprawling torrents that thunder out of the forest and then plough their way to the sea. Some have mouths big enough to swallow Barbados. But, even the biggest of them – the Essequibo, Corentyne and Marowijne – are intolerant of shipping; beyond ninety miles inland, nothing larger than a canoe gets through without being battered to bits. Once it was thought that these furious rivers all linked up, and that Guiana was really an agglomeration of islands, bobbing around in the froth.

But whatever the layout, water still rules. It dominates development, trims opportunities and seals off the world. It makes islanders of tribes, and supports long-lost communities of prospectors, Utopians and runaway slaves. It feeds malaria and nurtures some of the world’s most ambitious strains of dengue fever. Damp gets everywhere, rotting buildings and feet and making steam of the air. From the very earliest times human beings have realised that their best chance of surviving Guiana is by living right next to the sea. Even now, nine out of every ten of its inhabitants live on a long, muddy strip, barely ten miles wide.

It’s curious, life in the silt. Most of the houses have legs, and every town is built on a grid of velvety, green canals. Meanwhile, the Atlantic Ocean here is the colour of plaster, caused, it’s said, by sediments harvested in Peru, washed across the continent and disgorged by the Amazon. It makes for a beautiful world, luminously lush and drenchingly fecund. Not surprisingly, its inhabitants are proud of it and give it affectionate names. In Demerara they call their land ‘The Mudflat’ (and their neighbours the ‘mudheads’). But not every-one’s impressed. As one visiting English yachtsman wrote in 1882, ‘It appears a hopeless land of slime and fever, quite unfitted for man, unless it be for Tree-Indians, a low race of fish-eating savages …’

Naturally, this claggy, overgrown, fish-breathed coast was never immediately inviting. For years the newly emerging Europeans had steered well clear. In theory, Spain was the first to claim it (along with the rest of the western world) under the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. It was five years, however, before they sent a ship, and even then it didn’t stop. Another thirty years passed before anyone tried to land, only to be eaten by the locals. After that, Spanish interest in Guiana shrivelled, and the only part they ever occupied was the north-west end, now part of Venezuela, called ‘Guayana’. Meanwhile, the Portuguese colonised the southern flanks (now the Brazilian state of Amapá), and the bit in between was up for grabs.

It’s this bit of Guiana – the chunk in the middle – that interested me, and eventually it became the setting for these travels. It’s an area about twice the size of Great Britain, divided into three unequal, roughly rectangular shares: Guyana (formerly British Guiana), Suriname (formerly Dutch Guiana) and Guyane Française (also known as French Guiana). They are sometimes referred to – usefully, if a little inaccurately – as ‘The Guianas’, and form the only part of the South American mainland that was never either Spanish or Portuguese. What’s more, they’ve totally resisted the influences of the continent all around, never knowing salsa or tango, Bolívar, machismo, liberation theology or even the liberation movement. In fact, independence for two of the Guianas arrived only some 150 years after the rest of the continent, and even today Guyane remains a département of France. It’s almost as though the giant at their backs has never existed. Even as I write, there isn’t a single road that leads from the Guianas into the world beyond.

The story of how this oddity came about is surprisingly bloody. After the Spanish lost interest, it looked, for a moment, as though England might quietly acquire this coast. In 1595 Sir Walter Raleigh propagated a rumour that there was a city of gold here, that the women were biddable and cute, and that there was a fat partridge draped on every branch. Although these claims were rather obviously over-puffed, there was plenty of interest. First off, in 1597, was a barrister called John Ley, although he never planned to settle. Plenty of others did. But insolvency killed off most of their ideas, and ridicule the rest. Even the Pilgrim Fathers briefly toyed with the idea of planting New England here in Guiana (before a more sober assessment prevailed). Eventually, however, in 1604, colonisation began, with a settlement of English gentlemen in what is now Guyane. Most were dead within the year.

Their colony, however, heralded the beginning of a murderous game of musical chairs. For the next two hundred years, the three great European powers – France, Britain and Holland – scrambled around on this coast, snatching colonies and killing the previous incumbents. These wars always began and ended in Europe, and there were nine in all (First Dutch, Second Dutch, Grand Alliance, Spanish Succession, Jenkins’ Ear, Austrian Succession, Seven Years, American Independence and Napoleonic). At the end of each round no one was where they’d started, and the coast was in ruins. Modern-day Guyana changed hands nine times, Suriname six and Guyane seven. All three were seized at one point (1676) by the Dutch, and at another (1809) by Britain. Even today, the Guianas – as I’d soon discover – still reel from the impact of this antique chaos.