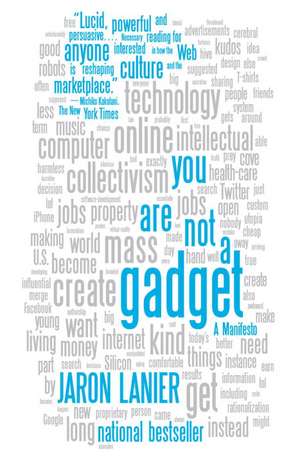

You Are Not a Gadget

Autor Jaron Lanieren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2011

A programmer, musician, and father of virtual reality technology, Jaron Lanier was a pioneer in digital media, and among the first to predict the revolutionary changes it would bring to our commerce and culture. Now, with the Web influencing virtually every aspect of our lives, he offers this provocative critique of how digital design is shaping society, for better and for worse.

Informed by Lanier’s experience and expertise as a computer scientist, You Are Not a Gadget discusses the technical and cultural problems that have unwittingly risen from programming choices—such as the nature of user identity—that were “locked-in” at the birth of digital media and considers what a future based on current design philosophies will bring. With the proliferation of social networks, cloud-based data storage systems, and Web 2.0 designs that elevate the “wisdom” of mobs and computer algorithms over the intelligence and wisdom of individuals, his message has never been more urgent.

Preț: 92.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 139

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.69€ • 18.27$ • 14.72£

17.69€ • 18.27$ • 14.72£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307389978

ISBN-10: 0307389979

Pagini: 223

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Colecția Vintage Books

ISBN-10: 0307389979

Pagini: 223

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Colecția Vintage Books

Notă biografică

Jaron Lanier is known as the father of virtual reality technology and has worked on the interface between computer science and medicine, physics, and neuroscience. He lives in Berkeley, California.

Visit the author's website at www.jaronlanier.com.

Visit the author's website at www.jaronlanier.com.

Extras

an apocalypse of self- abdication

THE IDEAS THAT I hope will not be locked in rest on a philosophical foundation that I sometimes call cybernetic totalism. It applies metaphors from certain strains of computer science to people and the rest of reality. Pragmatic objections to this philosophy are presented.

What Do You Do When the Techies Are Crazier Than the Luddites?

The Singularity is an apocalyptic idea originally proposed by John von Neumann, one of the inventors of digital computation, and elucidated by figures such as Vernor Vinge and Ray Kurzweil.

There are many versions of the fantasy of the Singularity. Here’s the one Marvin Minsky used to tell over the dinner table in the early 1980s: One day soon, maybe twenty or thirty years into the twenty- first century, computers and robots will be able to construct copies of themselves, and these copies will be a little better than the originals because of intelligent software. The second generation of robots will then make a third, but it will take less time, because of the improvements over the first

generation.

The process will repeat. Successive generations will be ever smarter and will appear ever faster. People might think they’re in control, until one fine day the rate of robot improvement ramps up so quickly that superintelligent robots will suddenly rule the Earth.

In some versions of the story, the robots are imagined to be microscopic, forming a “gray goo” that eats the Earth; or else the internet itself comes alive and rallies all the net- connected machines into an army to control the affairs of the planet. Humans might then enjoy immortality within virtual reality, because the global brain would be so huge that it would be absolutely easy—a no-brainer, if you will—for it to host all our consciousnesses for eternity.

The coming Singularity is a popular belief in the society of technologists. Singularity books are as common in a computer science department as Rapture images are in an evangelical bookstore.

(Just in case you are not familiar with the Rapture, it is a colorful belief in American evangelical culture about the Christian apocalypse. When I was growing up in rural New Mexico, Rapture paintings would often be found in places like gas stations or hardware stores. They would usually include cars crashing into each other because the virtuous drivers had suddenly disappeared, having been called to heaven just before the onset of hell on Earth. The immensely popular Left Behind novels also describe this scenario.)

There might be some truth to the ideas associated with the Singularity at the very largest scale of reality. It might be true that on some vast cosmic basis, higher and higher forms of consciousness inevitably arise, until the whole universe becomes a brain, or something along those lines. Even at much smaller scales of millions or even thousands of years, it is more exciting to imagine humanity evolving into a more wonderful state than we can presently articulate. The only alternatives would be extinction or stodgy stasis, which would be a little disappointing and sad, so let us hope for transcendence of the human condition, as we now

understand it.

The difference between sanity and fanaticism is found in how well the believer can avoid confusing consequential differences in timing. If you believe the Rapture is imminent, fixing the problems of this life might not be your greatest priority. You might even be eager to embrace wars and tolerate poverty and disease in others to bring about the conditions that could prod the Rapture into being. In the same way, if you believe the Singularity is coming soon, you might cease to design technology to serve humans, and prepare instead for the grand events it will bring.

But in either case, the rest of us would never know if you had been right. Technology working well to improve the human condition is detectable, and you can see that possibility portrayed in optimistic science fiction like Star Trek.

The Singularity, however, would involve people dying in the flesh and being uploaded into a computer and remaining conscious, or people simply being annihilated in an imperceptible instant before a new superconsciousness takes over the Earth. The Rapture and the Singularity share one thing in common: they can never be verified by the living.

You Need Culture to Even Perceive Information Technology

Ever more extreme claims are routinely promoted in the new digital climate. Bits are presented as if they were alive, while humans are transient fragments. Real people must have left all those anonymous comments on blogs and video clips, but who knows where they are now, or if they are dead? The digital hive is growing at the expense of individuality.

Kevin Kelly says that we don’t need authors anymore, that all the ideas of the world, all the fragments that used to be assembled into coherent books by identifiable authors, can be combined into one single, global book. Wired editor Chris Anderson proposes that science should no longer seek theories that scientists can understand, because the digital cloud will understand them better anyway.*

Antihuman rhetoric is fascinating in the same way that selfdestruction is fascinating: it offends us, but we cannot look away.

The antihuman approach to computation is one of the most baseless ideas in human history. A computer isn’t even there unless a person experiences it. There will be a warm mass of patterned silicon with electricity coursing through it, but the bits don’t mean anything without a cultured person to interpret them.

This is not solipsism. You can believe that your mind makes up the world, but a bullet will still kill you. A virtual bullet, however, doesn’t even exist unless there is a person to recognize it as a representation of a bullet. Guns are real in a way that computers are not.

Making People Obsolete So That Computers Seem More Advanced

Many of today’s Silicon Valley intellectuals seem to have embraced what used to be speculations as certainties, without the spirit of unbounded curiosity that originally gave rise to them. Ideas that were once tucked away in the obscure world of artificial intelligence labs have gone mainstream in tech culture. The first tenet of this new culture is that all of reality, including humans, is one big information system. That doesn’t mean we are condemned to a meaningless existence. Instead there is a new kind of manifest destiny that provides us with a mission to accomplish. The meaning of life, in this view, is making the digital system we

call reality function at ever- higher “levels of description.”

People pretend to know what “levels of description” means, but I doubt anyone really does. A web page is thought to represent a higher level of description than a single letter, while a brain is a higher level than a web page. An increasingly common extension of this notion is that the net as a whole is or soon will be a higher level than a brain. There’s nothing special about the place of humans in this scheme. Computers will soon get so big and fast and the net so rich with information that people will be obsolete, either left behind like the characters in Rapture novels or subsumed into some cyber-superhuman something.

Silicon Valley culture has taken to enshrining this vague idea and spreading it in the way that only technologists can. Since implementation speaks louder than words, ideas can be spread in the designs of software. If you believe the distinction between the roles of people and computers is starting to dissolve, you might express that—as some friends of mine at Microsoft once did—by designing features for a word processor that are supposed to know what you want, such as when you want to start an outline within your document. You might have had the experience of having Microsoft Word suddenly determine, at the wrong moment, that you are creating an indented outline. While I am all for the automation of petty tasks, this is different.

From my point of view, this type of design feature is nonsense, since you end up having to work more than you would otherwise in order to manipulate the software’s expectations of you. The real function of the feature isn’t to make life easier for people. Instead, it promotes a new philosophy: that the computer is evolving into a life-form that can understand people better than people can understand themselves.

Another example is what I call the “race to be most meta.” If a design like Facebook or Twitter depersonalizes people a little bit, then another service like Friendfeed— which may not even exist by the time this book is published— might soon come along to aggregate the previous layers of aggregation, making individual people even more abstract, and the illusion of high- level metaness more celebrated.

Information Doesn’t Deserve to Be Free

“Information wants to be free.” So goes the saying. Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, seems to have said it first.

I say that information doesn’t deserve to be free.

Cybernetic totalists love to think of the stuff as if it were alive and had its own ideas and ambitions. But what if information is inanimate? What if it’s even less than inanimate, a mere artifact of human thought? What if only humans are real, and information is not?

Of course, there is a technical use of the term “information” that refers to something entirely real. This is the kind of information that’s related to entropy. But that fundamental kind of information, which exists independently of the culture of an observer, is not the same as the kind we can put in computers, the kind that supposedly wants to be free.

Information is alienated experience.

You can think of culturally decodable information as a potential form of experience, very much as you can think of a brick resting on a ledge as storing potential energy. When the brick is prodded to fall, the energy is revealed. That is only possible because it was lifted into place at some point in the past.

In the same way, stored information might cause experience to be revealed if it is prodded in the right way. A file on a hard disk does indeed contain information of the kind that objectively exists. The fact that the bits are discernible instead of being scrambled into mush—the way heat scrambles things—is what makes them bits.

But if the bits can potentially mean something to someone, they can only do so if they are experienced. When that happens, a commonality of culture is enacted between the storer and the retriever of the bits. Experience is the only process that can de- alienate information.

Information of the kind that purportedly wants to be free is nothing but a shadow of our own minds, and wants nothing on its own. It will not suffer if it doesn’t get what it wants.

But if you want to make the transition from the old religion, where you hope God will give you an afterlife, to the new religion, where you hope to become immortal by getting uploaded into a computer, then you have to believe information is real and alive. So for you, it will be important to redesign human institutions like art, the economy, and the law to reinforce the perception that information is alive. You demand that the rest of us live in your new conception of a state religion. You need us to deify information to reinforce your faith.

*Chris Anderson, “The End of Theory,” Wired, June 23, 2008 (www.wired.com/science/discoveries/magazine/ 16- 07/pb_theory).

From the Hardcover edition.

THE IDEAS THAT I hope will not be locked in rest on a philosophical foundation that I sometimes call cybernetic totalism. It applies metaphors from certain strains of computer science to people and the rest of reality. Pragmatic objections to this philosophy are presented.

What Do You Do When the Techies Are Crazier Than the Luddites?

The Singularity is an apocalyptic idea originally proposed by John von Neumann, one of the inventors of digital computation, and elucidated by figures such as Vernor Vinge and Ray Kurzweil.

There are many versions of the fantasy of the Singularity. Here’s the one Marvin Minsky used to tell over the dinner table in the early 1980s: One day soon, maybe twenty or thirty years into the twenty- first century, computers and robots will be able to construct copies of themselves, and these copies will be a little better than the originals because of intelligent software. The second generation of robots will then make a third, but it will take less time, because of the improvements over the first

generation.

The process will repeat. Successive generations will be ever smarter and will appear ever faster. People might think they’re in control, until one fine day the rate of robot improvement ramps up so quickly that superintelligent robots will suddenly rule the Earth.

In some versions of the story, the robots are imagined to be microscopic, forming a “gray goo” that eats the Earth; or else the internet itself comes alive and rallies all the net- connected machines into an army to control the affairs of the planet. Humans might then enjoy immortality within virtual reality, because the global brain would be so huge that it would be absolutely easy—a no-brainer, if you will—for it to host all our consciousnesses for eternity.

The coming Singularity is a popular belief in the society of technologists. Singularity books are as common in a computer science department as Rapture images are in an evangelical bookstore.

(Just in case you are not familiar with the Rapture, it is a colorful belief in American evangelical culture about the Christian apocalypse. When I was growing up in rural New Mexico, Rapture paintings would often be found in places like gas stations or hardware stores. They would usually include cars crashing into each other because the virtuous drivers had suddenly disappeared, having been called to heaven just before the onset of hell on Earth. The immensely popular Left Behind novels also describe this scenario.)

There might be some truth to the ideas associated with the Singularity at the very largest scale of reality. It might be true that on some vast cosmic basis, higher and higher forms of consciousness inevitably arise, until the whole universe becomes a brain, or something along those lines. Even at much smaller scales of millions or even thousands of years, it is more exciting to imagine humanity evolving into a more wonderful state than we can presently articulate. The only alternatives would be extinction or stodgy stasis, which would be a little disappointing and sad, so let us hope for transcendence of the human condition, as we now

understand it.

The difference between sanity and fanaticism is found in how well the believer can avoid confusing consequential differences in timing. If you believe the Rapture is imminent, fixing the problems of this life might not be your greatest priority. You might even be eager to embrace wars and tolerate poverty and disease in others to bring about the conditions that could prod the Rapture into being. In the same way, if you believe the Singularity is coming soon, you might cease to design technology to serve humans, and prepare instead for the grand events it will bring.

But in either case, the rest of us would never know if you had been right. Technology working well to improve the human condition is detectable, and you can see that possibility portrayed in optimistic science fiction like Star Trek.

The Singularity, however, would involve people dying in the flesh and being uploaded into a computer and remaining conscious, or people simply being annihilated in an imperceptible instant before a new superconsciousness takes over the Earth. The Rapture and the Singularity share one thing in common: they can never be verified by the living.

You Need Culture to Even Perceive Information Technology

Ever more extreme claims are routinely promoted in the new digital climate. Bits are presented as if they were alive, while humans are transient fragments. Real people must have left all those anonymous comments on blogs and video clips, but who knows where they are now, or if they are dead? The digital hive is growing at the expense of individuality.

Kevin Kelly says that we don’t need authors anymore, that all the ideas of the world, all the fragments that used to be assembled into coherent books by identifiable authors, can be combined into one single, global book. Wired editor Chris Anderson proposes that science should no longer seek theories that scientists can understand, because the digital cloud will understand them better anyway.*

Antihuman rhetoric is fascinating in the same way that selfdestruction is fascinating: it offends us, but we cannot look away.

The antihuman approach to computation is one of the most baseless ideas in human history. A computer isn’t even there unless a person experiences it. There will be a warm mass of patterned silicon with electricity coursing through it, but the bits don’t mean anything without a cultured person to interpret them.

This is not solipsism. You can believe that your mind makes up the world, but a bullet will still kill you. A virtual bullet, however, doesn’t even exist unless there is a person to recognize it as a representation of a bullet. Guns are real in a way that computers are not.

Making People Obsolete So That Computers Seem More Advanced

Many of today’s Silicon Valley intellectuals seem to have embraced what used to be speculations as certainties, without the spirit of unbounded curiosity that originally gave rise to them. Ideas that were once tucked away in the obscure world of artificial intelligence labs have gone mainstream in tech culture. The first tenet of this new culture is that all of reality, including humans, is one big information system. That doesn’t mean we are condemned to a meaningless existence. Instead there is a new kind of manifest destiny that provides us with a mission to accomplish. The meaning of life, in this view, is making the digital system we

call reality function at ever- higher “levels of description.”

People pretend to know what “levels of description” means, but I doubt anyone really does. A web page is thought to represent a higher level of description than a single letter, while a brain is a higher level than a web page. An increasingly common extension of this notion is that the net as a whole is or soon will be a higher level than a brain. There’s nothing special about the place of humans in this scheme. Computers will soon get so big and fast and the net so rich with information that people will be obsolete, either left behind like the characters in Rapture novels or subsumed into some cyber-superhuman something.

Silicon Valley culture has taken to enshrining this vague idea and spreading it in the way that only technologists can. Since implementation speaks louder than words, ideas can be spread in the designs of software. If you believe the distinction between the roles of people and computers is starting to dissolve, you might express that—as some friends of mine at Microsoft once did—by designing features for a word processor that are supposed to know what you want, such as when you want to start an outline within your document. You might have had the experience of having Microsoft Word suddenly determine, at the wrong moment, that you are creating an indented outline. While I am all for the automation of petty tasks, this is different.

From my point of view, this type of design feature is nonsense, since you end up having to work more than you would otherwise in order to manipulate the software’s expectations of you. The real function of the feature isn’t to make life easier for people. Instead, it promotes a new philosophy: that the computer is evolving into a life-form that can understand people better than people can understand themselves.

Another example is what I call the “race to be most meta.” If a design like Facebook or Twitter depersonalizes people a little bit, then another service like Friendfeed— which may not even exist by the time this book is published— might soon come along to aggregate the previous layers of aggregation, making individual people even more abstract, and the illusion of high- level metaness more celebrated.

Information Doesn’t Deserve to Be Free

“Information wants to be free.” So goes the saying. Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, seems to have said it first.

I say that information doesn’t deserve to be free.

Cybernetic totalists love to think of the stuff as if it were alive and had its own ideas and ambitions. But what if information is inanimate? What if it’s even less than inanimate, a mere artifact of human thought? What if only humans are real, and information is not?

Of course, there is a technical use of the term “information” that refers to something entirely real. This is the kind of information that’s related to entropy. But that fundamental kind of information, which exists independently of the culture of an observer, is not the same as the kind we can put in computers, the kind that supposedly wants to be free.

Information is alienated experience.

You can think of culturally decodable information as a potential form of experience, very much as you can think of a brick resting on a ledge as storing potential energy. When the brick is prodded to fall, the energy is revealed. That is only possible because it was lifted into place at some point in the past.

In the same way, stored information might cause experience to be revealed if it is prodded in the right way. A file on a hard disk does indeed contain information of the kind that objectively exists. The fact that the bits are discernible instead of being scrambled into mush—the way heat scrambles things—is what makes them bits.

But if the bits can potentially mean something to someone, they can only do so if they are experienced. When that happens, a commonality of culture is enacted between the storer and the retriever of the bits. Experience is the only process that can de- alienate information.

Information of the kind that purportedly wants to be free is nothing but a shadow of our own minds, and wants nothing on its own. It will not suffer if it doesn’t get what it wants.

But if you want to make the transition from the old religion, where you hope God will give you an afterlife, to the new religion, where you hope to become immortal by getting uploaded into a computer, then you have to believe information is real and alive. So for you, it will be important to redesign human institutions like art, the economy, and the law to reinforce the perception that information is alive. You demand that the rest of us live in your new conception of a state religion. You need us to deify information to reinforce your faith.

*Chris Anderson, “The End of Theory,” Wired, June 23, 2008 (www.wired.com/science/discoveries/magazine/ 16- 07/pb_theory).

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

A New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Boston Globe Bestseller

“Lucid, powerful and persuasive. . . . Necessary reading for anyone interested in how the Web and the software we use every day are reshaping culture and the marketplace.”

—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“Persuasive. . . . Lanier is the first great apostate of the Internet era.”

—Newsweek

“Thrilling and thought-provoking. . . . A necessary corrective in the echo chamber of technology debates.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Mind-bending, exuberant, brilliant. . . . Lanier dares to say the forbidden.”

—The Washington Post

“With an expertise earned through decades of work in the field, Lanier challenges us to express our essential humanity via 21st century technology instead of disappearing in it. . . . [You Are Not a Gadget] compels readers to take a fresh look at the power—and limitations—of human interaction in a socially networked world.”

—Time (“The 2010 Time 100”)

“Lanier is not of my generation, but he knows and understands us well, and has written a short and frightening book, You Are Not a Gadget, which chimes with my own discomfort, while coming from a position of real knowledge and insight, both practical and philosophical.”

—Zadie Smith, The New York Review of Books

“Sparky, thought-provoking. . . . Lanier clearly enjoys rethinking received tech wisdom: his book is a refreshing change from Silicon Valley’s usual hype.”

—New Scientist

“Important. . . . At the bottom of Lanier’s cyber-tinkering is a fundamentally humanist faith in technology. . . . His mind is a fascinating place to hang out.”

—Los Angeles Times

“A call for a more humanistic—to say nothing of humane—alternative future in which the individual is celebrated more than the crowd and the unique more than the homogenized. . . . You Are Not a Gadget may be its own best argument for exalting the creativity of the individual over the collective efforts of the ‘hive mind.’ It’s the work of a singular visionary.”

—Bloomberg News

“A bracing dose of economic realism and Randian philosophy for all those techno utopianists with their heads in the cloud. . . . [Lanier is] a true iconoclast. . . . He offers the sort of originality of thought he finds missing on the Web.”

—The Miami Herald

“For those who wish to read to think, and read to transform, You Are Not a Gadget is a book to begin the 2010s. . . . It is raw, raucous and unexpected. It is also a hell of a lot of fun.”

—Times Higher Education

“[Lanier] confronts the big issues with bracing directness. . . . The reader sits up. One of the insider’s insiders of the computing world seems to have gone rogue.”

—The Boston Globe

“Gadget is an essential first step at harnessing a post-Google world.”

—The Stranger (Seattle)

“Lanier turns a philosopher’s eye to our everyday online tools. . . . The reader is compelled to engage with his work, to assent, contradict, and contemplate. . . . Lovers of the Internet and all its possibilities owe it to themselves to plunge into Lanier’s manifesto and look hard in the mirror. He’s not telling us what to think; he’s challenging us to take a hard look at our cyberculture, and emerge with new creative inspiration.”

—Flavorwire

“Poetic and prophetic, this could be the most important book of the year. . . . Read this book and rise up against net regimentation!”

—The Times (London)

“[Lanier’s] argument will make intuitive sense to anyone concerned with questions of propriety, responsibility, and authenticity.”

—The New Yorker

“Inspired, infuriating and utterly necessary. . . . Lanier tells of the loss of a hi-tech Eden, of the fall from play into labour, obedience and faith. Welcome to the century’s first great plea for a ‘new digital humanism’ against the networked conformity of cyber-space. This eloquent, eccentric riposte comes from a sage of the virtual world who assures us that, in spite of its crimes and follies, ‘I love the internet.’ That provenance will only deepen its impact, and broaden its appeal.”

—The Independent (London)

“Fascinating and provocative. . . . Destined to become a must-read for both critics and advocates of online-based technology and culture.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Lucid, powerful and persuasive. . . . Necessary reading for anyone interested in how the Web and the software we use every day are reshaping culture and the marketplace.”

—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“Persuasive. . . . Lanier is the first great apostate of the Internet era.”

—Newsweek

“Thrilling and thought-provoking. . . . A necessary corrective in the echo chamber of technology debates.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Mind-bending, exuberant, brilliant. . . . Lanier dares to say the forbidden.”

—The Washington Post

“With an expertise earned through decades of work in the field, Lanier challenges us to express our essential humanity via 21st century technology instead of disappearing in it. . . . [You Are Not a Gadget] compels readers to take a fresh look at the power—and limitations—of human interaction in a socially networked world.”

—Time (“The 2010 Time 100”)

“Lanier is not of my generation, but he knows and understands us well, and has written a short and frightening book, You Are Not a Gadget, which chimes with my own discomfort, while coming from a position of real knowledge and insight, both practical and philosophical.”

—Zadie Smith, The New York Review of Books

“Sparky, thought-provoking. . . . Lanier clearly enjoys rethinking received tech wisdom: his book is a refreshing change from Silicon Valley’s usual hype.”

—New Scientist

“Important. . . . At the bottom of Lanier’s cyber-tinkering is a fundamentally humanist faith in technology. . . . His mind is a fascinating place to hang out.”

—Los Angeles Times

“A call for a more humanistic—to say nothing of humane—alternative future in which the individual is celebrated more than the crowd and the unique more than the homogenized. . . . You Are Not a Gadget may be its own best argument for exalting the creativity of the individual over the collective efforts of the ‘hive mind.’ It’s the work of a singular visionary.”

—Bloomberg News

“A bracing dose of economic realism and Randian philosophy for all those techno utopianists with their heads in the cloud. . . . [Lanier is] a true iconoclast. . . . He offers the sort of originality of thought he finds missing on the Web.”

—The Miami Herald

“For those who wish to read to think, and read to transform, You Are Not a Gadget is a book to begin the 2010s. . . . It is raw, raucous and unexpected. It is also a hell of a lot of fun.”

—Times Higher Education

“[Lanier] confronts the big issues with bracing directness. . . . The reader sits up. One of the insider’s insiders of the computing world seems to have gone rogue.”

—The Boston Globe

“Gadget is an essential first step at harnessing a post-Google world.”

—The Stranger (Seattle)

“Lanier turns a philosopher’s eye to our everyday online tools. . . . The reader is compelled to engage with his work, to assent, contradict, and contemplate. . . . Lovers of the Internet and all its possibilities owe it to themselves to plunge into Lanier’s manifesto and look hard in the mirror. He’s not telling us what to think; he’s challenging us to take a hard look at our cyberculture, and emerge with new creative inspiration.”

—Flavorwire

“Poetic and prophetic, this could be the most important book of the year. . . . Read this book and rise up against net regimentation!”

—The Times (London)

“[Lanier’s] argument will make intuitive sense to anyone concerned with questions of propriety, responsibility, and authenticity.”

—The New Yorker

“Inspired, infuriating and utterly necessary. . . . Lanier tells of the loss of a hi-tech Eden, of the fall from play into labour, obedience and faith. Welcome to the century’s first great plea for a ‘new digital humanism’ against the networked conformity of cyber-space. This eloquent, eccentric riposte comes from a sage of the virtual world who assures us that, in spite of its crimes and follies, ‘I love the internet.’ That provenance will only deepen its impact, and broaden its appeal.”

—The Independent (London)

“Fascinating and provocative. . . . Destined to become a must-read for both critics and advocates of online-based technology and culture.”

—Publishers Weekly

Descriere

Lanier, a Silicon Valley visionary, offers this provocative and cautionary look at the way technology is transforming lives for better and for worse.