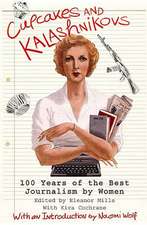

A Jury Of Her Peers

Autor Elaine Showalteren Limba Engleză Paperback – sep 2010

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 76.47 lei 22-36 zile | |

| Little Brown Book Group – sep 2010 | 76.47 lei 22-36 zile | |

| Vintage Books USA – 31 dec 2009 | 133.94 lei 22-36 zile |

Preț: 76.47 lei

Preț vechi: 97.77 lei

-22% Nou

Puncte Express: 115

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.64€ • 15.25$ • 12.18£

14.64€ • 15.25$ • 12.18£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 16-30 decembrie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781844080809

ISBN-10: 1844080803

Pagini: 704

Dimensiuni: 127 x 195 x 47 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Little Brown Book Group

ISBN-10: 1844080803

Pagini: 704

Dimensiuni: 127 x 195 x 47 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Little Brown Book Group

Notă biografică

Elaine Showalter was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1941. From 1967 to 1984 she taught English and Women's Studies at Rutgers University, and she now chairs the department of English at Princeton University.

Extras

I

A New Literature Springs Up in the New World

From the very beginning, women were creating the new words of the New World. The first women writers in America, Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672) and Mary Rowlandson (1637–1711), were born in England and endured the harrowing three-month voyage of storm, seasickness, and starvation across the North Atlantic. In Massachusetts, where they settled, they led lives of extraordinary danger and deprivation. Both married and had children; they thought of themselves primarily as good wives and mothers. Both made the glory of God their justification for writing, but they prefigured themes and concerns that would preoccupy American women writers for the next 150 years and more—Bradstreet, the poet, writing about the intimacies and agonies of domestic life, including pregnancy and maternity, the death of three of her grandchildren, and the destruction of her home by fire; and Rowlandson, writing a narrative of her captivity by Narragansett Indians, and pioneering the great American theme of interracial experience in the encounter with Native American culture.

Both Bradstreet and Rowlandson entered print shielded by the authorization, legitimization, and testimony of men. In Bradstreet’s case, no fewer than eleven men wrote testimonials and poems praising her piety and industry, prefatory materials almost as long as the thirteen poems in the book. In his introductory letter, John Woodbridge, her brother-in-law, stood guarantee that Bradstreet herself had written the poems, that she had not initiated their publication, and that she had neglected no housekeeping chore in their making: “these Poems are the fruit but of some few houres, curtailed from her sleep and other refreshments.” Rowlandson’s narrative too came with “a preface to the reader” signed “Per Amicum” (“By a Friend”), probably the minister Increase Mather, which explained that although the work had been “penned by this Gentlewoman,” she had written it as a “Memorandum of Gods dealing with her,” and it was a “pious scope, which deserves both commendation and imitation.” The author had not sought publication of her narrative out of vanity; rather,

some Friends having obtained a sight of it, could not but be so much affected with the many passages of working providence discovered therein, as to judge it worthy of publick view, and altogether unmeet that such works of God should be hid from present and future Generation: and therefore though this Gentlewoman’s modesty would not thrust it into the Press, yet her gratitude to God, made her not hardly perswadable to let it pass, that God might have his due glory, and others benefit by it as well as her selfe.

Having given a lengthy defense of the virtues of the book, the Friend concluded with the hope that “none will cast any reflection upon this Gentlewoman, on the score of this publication,” and warned that any who did “may be reckoned with the nine Lepers,” symbols of ingratitude. Apparently no one dared come forward to complain about Rowlandson after this endorsement.

We know that New England Puritans in the seventeenth century believed that men were intellectually superior to women, and that God had designed it so. They were notoriously unsympathetic to women who defied God’s plan for the sexes by conspicuous learning or reading, and they could be hostile to women who went outside their sphere by preaching or writing. The most official expression of this hostility was the trial of Anne Hutchinson in 1637. Hutchinson belonged to a dissident sect, but she had also been leading her own discussion groups for women. Tried for “traducing the ministers” and for blasphemy while she was pregnant with her fifteenth child, Hutchinson was excommunicated and forced to leave the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with her husband and children. The entire Hutchinson family, with the exception of one daughter, were killed by Indians in 1643. In 1645, when Ann Yale Hopkins, the wife of Governor Edward Hopkins of Hartford, became insane, John Winthrop blamed her “giving herself wholly to reading and writing,” rather than the hardships of colonial life, for her breakdown. “If she had attended to her household affairs, and such things as belong to women, and not gone out of her way and calling to meddle such things as are proper for men, whose minds are stronger . . . she had kept her wits.”

Despite these instances, the shared hardships of life in the New World gave women an existential equality with men that allowed Bradstreet and Rowlandson self-expression. Both men and women shared cold and hunger, faced disease and death, and risked captivity and massacre. Almost two hundred members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony died during the first year. Women had to do the hard physical labor of cooking, baking, cleaning, dairying, spinning, weaving, sewing, washing, and ironing. They endured the dangers of childbirth in the wilderness, nursed babies, and often buried them. While in strict religious terms “goodwives” were not supposed to trespass on the masculine sphere of literary expression, in reality there was more flexibility and tolerance. As two of her modern editors observe, “Bradstreet was not censured, disciplined, or in any way ostracized for her art, thought, or personal assertiveness, so far as we know. Rather, she was praised and encouraged; and there are no indications that the males in her life treated her as ‘property.’ If anything, she was treated as at least an intellectual equal.”1

A Poet Crowned with Parsley—Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet’s The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (1650) was the first book by a woman living in America, although it was actually published in London and entered in the Stationers’ Register. Bradstreet wrote with both an awareness of her gender, and a sense of rootedness in New England Puritan culture. Adrienne Rich has paid tribute to her achievement and summed up her inspiring example for future American women poets:

Anne Bradstreet happened to be one of the first American women inhabiting a time and place in which heroism was a necessity of life, and men and women were fighting for survival both as individuals and as a community. To find room in that life for any mental activity . . . was an act of great self-assertion and vitality. To have written poems . . . while rearing eight children, lying frequently sick, keeping house at the edge of the wilderness, was to have managed a poet’s range and extension within confines as severe as any American poet has confronted.2

But Bradstreet was much more than a heroic female survivor who courageously managed to compose poetry in her spare time. She was also a strong, original poet whose work can be read today with enjoyment and emotion, a woman who wrote great poems expressing timeless themes of love, loss, doubt, and faith. Despite her strict Puritan beliefs, she had wit and a sense of humor. And while she dutifully imitated the prevailing models of male poetic excellence, from Sir Philip Sidney to the French Protestant poet Guillaume Du Bartas (whose huge unfinished epic of the Creation was among the Puritans’ most revered texts), she also explored some of the most central issues for the development of American women’s writing—how to make domestic topics worthy of serious literature, and how to use strong and memorable language without ceasing to be womanly.

We don’t know all the facts of Anne Bradstreet’s life, but what we do know suggests that growing up in England she began to think of herself as a poet from an early age. While her brother went to Cambridge, she was tutored in Greek, Latin, French, and Hebrew by her father, Thomas Dudley, the steward to the Earl of Lincoln, and had access to the earl’s large library. She had begun to compose her own poems by the time she was sixteen, when she married twenty-five-year-old Simon Bradstreet, a graduate of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, who had assisted her father in his stewardship. The marriage was a love match, and indeed Bradstreet would dedicate to Simon one of the most beautiful poems a woman ever wrote about her husband.

In early April of 1630, the Bradstreets and the Dudleys were among the Puritan members of the New England Company who embarked on a three-month voyage to America on the Arbella, the flagship of a little fleet of four vessels. Another passenger, John Winthrop, who would become the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, preached a famous sermon to the pilgrims aboard, declaring that God was supporting their expedition, and that their settlement would be like “a Citty upon a Hill,” with the “eyes of all people” upon them. But when they arrived in Salem on June 12, 1630, they discovered that disease and starvation had decimated the small Bay Colony, and many among their own numbers died in the first weeks. The Salem settlers had been living in caves, huts, and wigwams, and had not even been able to plant crops. For the next few years the pioneers battled to survive, eating clams, mussels, nuts, and acorns; building shelters; and facing cold, hunger, and illness as well as anxiety and homesickness.

Both Bradstreet’s father and her husband served as governors of the struggling colony. For the difficult first five years of their marriage, Anne was unable to have a child. In her journal she confessed: “It pleased God to keep me a long time without a child, which was a great grief to me, and cost me many prayers and tears before I obtaind one, and after him gave me many more.” She also became ill and was bedridden for several months in 1632 with fever and coughing. When she recovered, she wrote her first poem, “Upon a Fit of Sickness,” thanking God for his mercy in sparing her life. And the following year, she gave birth to her first son, Samuel.

Anne Hutchinson came to New England in 1634, and Bradstreet witnessed the events of her rise and fall. But as Charlotte Gordon points out, “ironically, Mistress Hutchinson’s downfall ushered in the most fertile decade of Anne Bradstreet’s life—fertile in every sense of the word.” Already the mother of a son and a daughter, Bradstreet gave birth to five more children during these years. From 1638 to 1648, she also “wrote more than six thousand lines of poetry, more than almost any other English writer on either side of the Atlantic composed in an entire lifetime. For most of this time, she was either pregnant, recovering from childbirth, or nursing an infant, establishing herself as a woman blessed by God, the highest commendation a New England Puritan mother could receive.”3

The poems Bradstreet was writing were intellectual and scholarly, formally influenced by English and European masters. But she was aroused and provoked by the great political events taking place in England in the 1640s, particularly the English Civil War, which led to the execution of Charles I. Five thousand of the six thousand lines of poetry she composed during the decade came from her long poem in heroic couplets, “The Four Monarchies,” in which she chronicled the pre-Christian empires of Assyria, Persia, Greece, and Rome, examining the legitimacy of kings and emperors. These were not the standard subjects of pious women’s verse, and in a “Prologue” to her poems, Bradstreet protected herself from criticism by insisting that she was a modest woman who had no intention of competing with male epic poets:

To sing of wars, of captains, and of kings,

Of cities founded, commonwealths begun,

For my mean pen are too superior things . . .

Let poets and historians set these forth,

My obscure lines shall not so dim their worth.

Like English women poets of her time, such as Anne Finch and Anne Killigrew, she emphasized her inferiority and temerity in writing at all, calling her Muse “foolish, broken, blemished.” While men rightly contended for fame and precedence, Bradstreet flatteringly claimed, she was content with her humble domestic niche, and her poems would make those of her male contemporaries look even more impressive:

If e’er you deign these lowly lines your eyes,

Give thyme or Parsley wreath, I ask no Bayes.

This mean and unrefined ore of mine

Will make your glist’ring gold but more to shine.

Instead of striving for the bay or laurel wreath, she asked only for a wreath of parsley and thyme, kitchen herbs rather than Parnassian prizes. Bradstreet was the Poet Parsleyate, the woman poet whose domestic work enabled the leisured creativity of men; but her imagery of the humble kitchen of Parnassus would be echoed in many heartfelt cries by the American women writers who came after her.

The humility of these lines, however, was balanced by her request for men to give women poets the space and the chance they deserved:

Men have precedency and still excel,

It is but vain unjustly to wage war;

Men can do best, and Women know it well.

Preeminence in all and each is yours;

Yet grant some small acknowledgment of ours.

In 1649, Bradstreet’s brother-in-law, the Reverend John Woodbridge, who was in England acting as a clerical adviser to the Puritan army, arranged to have her poems published by a bookseller in Popes Head Alley, London, under the title The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America, or Severall Poems, compiled with great variety of Wit and Learning, full of delight. As the cover went on to explain, the book included “a complete discourse and description of the Four Elements, Constitutions, Ages of Man, Seasons of the Year” and “an Exact Epitome of the Four Monarchies . . . Also a Dialogue between Old England and New, concerning the late troubles, with divers other pleasant and serious Poems.” In his prefatory verse, “To my Dear Sister, the Author of These Poems,” he congratulated her on her achievements:

What you have done, the Sun shall witnesse bear,

That for a womans Worke ’tis very rare;

And if the Nine vouchsafe the Tenth a place,

I think they rightly may yield you that grace.

In England, The Tenth Muse was well received as evidence of the genius of the woman of the New World, and became one of the “most vendible,” or best-selling, books of the period, at the top of the list with Shakespeare and Milton. In New England, it was widely read and esteemed.4

From the Hardcover edition.

A New Literature Springs Up in the New World

From the very beginning, women were creating the new words of the New World. The first women writers in America, Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672) and Mary Rowlandson (1637–1711), were born in England and endured the harrowing three-month voyage of storm, seasickness, and starvation across the North Atlantic. In Massachusetts, where they settled, they led lives of extraordinary danger and deprivation. Both married and had children; they thought of themselves primarily as good wives and mothers. Both made the glory of God their justification for writing, but they prefigured themes and concerns that would preoccupy American women writers for the next 150 years and more—Bradstreet, the poet, writing about the intimacies and agonies of domestic life, including pregnancy and maternity, the death of three of her grandchildren, and the destruction of her home by fire; and Rowlandson, writing a narrative of her captivity by Narragansett Indians, and pioneering the great American theme of interracial experience in the encounter with Native American culture.

Both Bradstreet and Rowlandson entered print shielded by the authorization, legitimization, and testimony of men. In Bradstreet’s case, no fewer than eleven men wrote testimonials and poems praising her piety and industry, prefatory materials almost as long as the thirteen poems in the book. In his introductory letter, John Woodbridge, her brother-in-law, stood guarantee that Bradstreet herself had written the poems, that she had not initiated their publication, and that she had neglected no housekeeping chore in their making: “these Poems are the fruit but of some few houres, curtailed from her sleep and other refreshments.” Rowlandson’s narrative too came with “a preface to the reader” signed “Per Amicum” (“By a Friend”), probably the minister Increase Mather, which explained that although the work had been “penned by this Gentlewoman,” she had written it as a “Memorandum of Gods dealing with her,” and it was a “pious scope, which deserves both commendation and imitation.” The author had not sought publication of her narrative out of vanity; rather,

some Friends having obtained a sight of it, could not but be so much affected with the many passages of working providence discovered therein, as to judge it worthy of publick view, and altogether unmeet that such works of God should be hid from present and future Generation: and therefore though this Gentlewoman’s modesty would not thrust it into the Press, yet her gratitude to God, made her not hardly perswadable to let it pass, that God might have his due glory, and others benefit by it as well as her selfe.

Having given a lengthy defense of the virtues of the book, the Friend concluded with the hope that “none will cast any reflection upon this Gentlewoman, on the score of this publication,” and warned that any who did “may be reckoned with the nine Lepers,” symbols of ingratitude. Apparently no one dared come forward to complain about Rowlandson after this endorsement.

We know that New England Puritans in the seventeenth century believed that men were intellectually superior to women, and that God had designed it so. They were notoriously unsympathetic to women who defied God’s plan for the sexes by conspicuous learning or reading, and they could be hostile to women who went outside their sphere by preaching or writing. The most official expression of this hostility was the trial of Anne Hutchinson in 1637. Hutchinson belonged to a dissident sect, but she had also been leading her own discussion groups for women. Tried for “traducing the ministers” and for blasphemy while she was pregnant with her fifteenth child, Hutchinson was excommunicated and forced to leave the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with her husband and children. The entire Hutchinson family, with the exception of one daughter, were killed by Indians in 1643. In 1645, when Ann Yale Hopkins, the wife of Governor Edward Hopkins of Hartford, became insane, John Winthrop blamed her “giving herself wholly to reading and writing,” rather than the hardships of colonial life, for her breakdown. “If she had attended to her household affairs, and such things as belong to women, and not gone out of her way and calling to meddle such things as are proper for men, whose minds are stronger . . . she had kept her wits.”

Despite these instances, the shared hardships of life in the New World gave women an existential equality with men that allowed Bradstreet and Rowlandson self-expression. Both men and women shared cold and hunger, faced disease and death, and risked captivity and massacre. Almost two hundred members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony died during the first year. Women had to do the hard physical labor of cooking, baking, cleaning, dairying, spinning, weaving, sewing, washing, and ironing. They endured the dangers of childbirth in the wilderness, nursed babies, and often buried them. While in strict religious terms “goodwives” were not supposed to trespass on the masculine sphere of literary expression, in reality there was more flexibility and tolerance. As two of her modern editors observe, “Bradstreet was not censured, disciplined, or in any way ostracized for her art, thought, or personal assertiveness, so far as we know. Rather, she was praised and encouraged; and there are no indications that the males in her life treated her as ‘property.’ If anything, she was treated as at least an intellectual equal.”1

A Poet Crowned with Parsley—Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet’s The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (1650) was the first book by a woman living in America, although it was actually published in London and entered in the Stationers’ Register. Bradstreet wrote with both an awareness of her gender, and a sense of rootedness in New England Puritan culture. Adrienne Rich has paid tribute to her achievement and summed up her inspiring example for future American women poets:

Anne Bradstreet happened to be one of the first American women inhabiting a time and place in which heroism was a necessity of life, and men and women were fighting for survival both as individuals and as a community. To find room in that life for any mental activity . . . was an act of great self-assertion and vitality. To have written poems . . . while rearing eight children, lying frequently sick, keeping house at the edge of the wilderness, was to have managed a poet’s range and extension within confines as severe as any American poet has confronted.2

But Bradstreet was much more than a heroic female survivor who courageously managed to compose poetry in her spare time. She was also a strong, original poet whose work can be read today with enjoyment and emotion, a woman who wrote great poems expressing timeless themes of love, loss, doubt, and faith. Despite her strict Puritan beliefs, she had wit and a sense of humor. And while she dutifully imitated the prevailing models of male poetic excellence, from Sir Philip Sidney to the French Protestant poet Guillaume Du Bartas (whose huge unfinished epic of the Creation was among the Puritans’ most revered texts), she also explored some of the most central issues for the development of American women’s writing—how to make domestic topics worthy of serious literature, and how to use strong and memorable language without ceasing to be womanly.

We don’t know all the facts of Anne Bradstreet’s life, but what we do know suggests that growing up in England she began to think of herself as a poet from an early age. While her brother went to Cambridge, she was tutored in Greek, Latin, French, and Hebrew by her father, Thomas Dudley, the steward to the Earl of Lincoln, and had access to the earl’s large library. She had begun to compose her own poems by the time she was sixteen, when she married twenty-five-year-old Simon Bradstreet, a graduate of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, who had assisted her father in his stewardship. The marriage was a love match, and indeed Bradstreet would dedicate to Simon one of the most beautiful poems a woman ever wrote about her husband.

In early April of 1630, the Bradstreets and the Dudleys were among the Puritan members of the New England Company who embarked on a three-month voyage to America on the Arbella, the flagship of a little fleet of four vessels. Another passenger, John Winthrop, who would become the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, preached a famous sermon to the pilgrims aboard, declaring that God was supporting their expedition, and that their settlement would be like “a Citty upon a Hill,” with the “eyes of all people” upon them. But when they arrived in Salem on June 12, 1630, they discovered that disease and starvation had decimated the small Bay Colony, and many among their own numbers died in the first weeks. The Salem settlers had been living in caves, huts, and wigwams, and had not even been able to plant crops. For the next few years the pioneers battled to survive, eating clams, mussels, nuts, and acorns; building shelters; and facing cold, hunger, and illness as well as anxiety and homesickness.

Both Bradstreet’s father and her husband served as governors of the struggling colony. For the difficult first five years of their marriage, Anne was unable to have a child. In her journal she confessed: “It pleased God to keep me a long time without a child, which was a great grief to me, and cost me many prayers and tears before I obtaind one, and after him gave me many more.” She also became ill and was bedridden for several months in 1632 with fever and coughing. When she recovered, she wrote her first poem, “Upon a Fit of Sickness,” thanking God for his mercy in sparing her life. And the following year, she gave birth to her first son, Samuel.

Anne Hutchinson came to New England in 1634, and Bradstreet witnessed the events of her rise and fall. But as Charlotte Gordon points out, “ironically, Mistress Hutchinson’s downfall ushered in the most fertile decade of Anne Bradstreet’s life—fertile in every sense of the word.” Already the mother of a son and a daughter, Bradstreet gave birth to five more children during these years. From 1638 to 1648, she also “wrote more than six thousand lines of poetry, more than almost any other English writer on either side of the Atlantic composed in an entire lifetime. For most of this time, she was either pregnant, recovering from childbirth, or nursing an infant, establishing herself as a woman blessed by God, the highest commendation a New England Puritan mother could receive.”3

The poems Bradstreet was writing were intellectual and scholarly, formally influenced by English and European masters. But she was aroused and provoked by the great political events taking place in England in the 1640s, particularly the English Civil War, which led to the execution of Charles I. Five thousand of the six thousand lines of poetry she composed during the decade came from her long poem in heroic couplets, “The Four Monarchies,” in which she chronicled the pre-Christian empires of Assyria, Persia, Greece, and Rome, examining the legitimacy of kings and emperors. These were not the standard subjects of pious women’s verse, and in a “Prologue” to her poems, Bradstreet protected herself from criticism by insisting that she was a modest woman who had no intention of competing with male epic poets:

To sing of wars, of captains, and of kings,

Of cities founded, commonwealths begun,

For my mean pen are too superior things . . .

Let poets and historians set these forth,

My obscure lines shall not so dim their worth.

Like English women poets of her time, such as Anne Finch and Anne Killigrew, she emphasized her inferiority and temerity in writing at all, calling her Muse “foolish, broken, blemished.” While men rightly contended for fame and precedence, Bradstreet flatteringly claimed, she was content with her humble domestic niche, and her poems would make those of her male contemporaries look even more impressive:

If e’er you deign these lowly lines your eyes,

Give thyme or Parsley wreath, I ask no Bayes.

This mean and unrefined ore of mine

Will make your glist’ring gold but more to shine.

Instead of striving for the bay or laurel wreath, she asked only for a wreath of parsley and thyme, kitchen herbs rather than Parnassian prizes. Bradstreet was the Poet Parsleyate, the woman poet whose domestic work enabled the leisured creativity of men; but her imagery of the humble kitchen of Parnassus would be echoed in many heartfelt cries by the American women writers who came after her.

The humility of these lines, however, was balanced by her request for men to give women poets the space and the chance they deserved:

Men have precedency and still excel,

It is but vain unjustly to wage war;

Men can do best, and Women know it well.

Preeminence in all and each is yours;

Yet grant some small acknowledgment of ours.

In 1649, Bradstreet’s brother-in-law, the Reverend John Woodbridge, who was in England acting as a clerical adviser to the Puritan army, arranged to have her poems published by a bookseller in Popes Head Alley, London, under the title The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America, or Severall Poems, compiled with great variety of Wit and Learning, full of delight. As the cover went on to explain, the book included “a complete discourse and description of the Four Elements, Constitutions, Ages of Man, Seasons of the Year” and “an Exact Epitome of the Four Monarchies . . . Also a Dialogue between Old England and New, concerning the late troubles, with divers other pleasant and serious Poems.” In his prefatory verse, “To my Dear Sister, the Author of These Poems,” he congratulated her on her achievements:

What you have done, the Sun shall witnesse bear,

That for a womans Worke ’tis very rare;

And if the Nine vouchsafe the Tenth a place,

I think they rightly may yield you that grace.

In England, The Tenth Muse was well received as evidence of the genius of the woman of the New World, and became one of the “most vendible,” or best-selling, books of the period, at the top of the list with Shakespeare and Milton. In New England, it was widely read and esteemed.4

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Exhilarating, provocative, revelatory, magisterial . . . The celebrated get their due . . . and so do the forgotten.”

—Slate

“A work of astonishing vision, breadth, intelligence, and audacity. . . . Sure to be required reading for all who have an interest in American literary history.”

—Joyce Carol Oates

“[A] grand new work of literary history . . . A critical standout . . . [Showalter] opines with zest on the personalities and books of the writers here . . . I do relish her critical gusto and guts . . . [She] has inspired me.”

—Maureen Corrigan, Fresh Air, National Public Radio

“Remarkable. . . . A Jury of Her Peers does an enormous service, houses a drop-dead reading list and gives the reader a fluid framework for the great (much of it still undiscovered) wealth of writing by women in this country.”

— The Los Angeles Times

“Impressively researched. . . . Generous, thought-provoking. . . . [Showalter is] less polarized and more nuanced than other feminist critics of her generation . . . She is a lively and incisive guide, the perfect Virgil for our quest.” —The Washington Post

“Enlightening . . . the book may be dipped into at any chapter with much reward . . . . Showalter captures so well, often in just a few paragraphs, the image of the women she writes about. . . . Reading A Jury of Her Peers is not only an education in literary history, it is eminently satisfactory intellectual nourishment. 4 out of 4 stars.” —Free Press

“[A] vast democratic volume . . . . Vivid . . . extremely readable and enlightening . . . . Her short, incisive biographies offer a glimpse into the exotic travails of the past and the eternal concerns of female experience . . . [A] ranging, inclusive history . . . . likely to become an important and valuable resource for anyone interested in women’s history.” —The New York Times Book Review

“A delicious compendium, a book that belongs in literature courses, of course, but also in writerly libraries and in the hands of anyone who enjoys reading about writers’ lives. . . . Essential.” —Barnes & Noble Review

“Clear-sighted, ambitious . . . minutely researched and rich with opinion, anecdotes, samples, and interpretation. . . . Monumental.” —Elle

“Absorbing. . . . excellent. . . . insightful. . . . the prose is so good that the 500-plus-page book also works as an absorbing cover-to-cover read. . . . Showalter does not try to force any of these writers into uncomfortable slots in any kind of artificial female pantheon. These writers are all individuals, and Showalter treats them as such.” —The Christian Science Monitor

“Elaine Showalter has delivered the first literary history of American women ever published, and the result is a riveting journey with scarcely a becalmed page . . . rich, readable . . . an immensely valuable work . . . vibrant regardless of where one dips in.” —The Seattle Times

“Accessible and readable. Brimming with wit and insight . . . . This monumental book will greatly enrich our understanding of American literary history and our culture.” —Tuscon Citizen, Recommended New Title

“Showalter may have written the perfect book-group book: Not only is it fascinating on its own, but it also opens up possibilities for decades of further reading. . . . Like a raucous party, with some squabbling going on in the darker corners. . . . Showalter’s prose is lively, and she has no problem expressing her opinions” —The Columbus Dispatch

“A breathtaking overview of the intersections of gender and genre in American letters. . . . With its frank assessments, impressive research and expansive scope, A Jury of Her Peers belongs on the shelf of any reader interested in the development of women’s writing in America.” —Ms. Magazine

—Slate

“A work of astonishing vision, breadth, intelligence, and audacity. . . . Sure to be required reading for all who have an interest in American literary history.”

—Joyce Carol Oates

“[A] grand new work of literary history . . . A critical standout . . . [Showalter] opines with zest on the personalities and books of the writers here . . . I do relish her critical gusto and guts . . . [She] has inspired me.”

—Maureen Corrigan, Fresh Air, National Public Radio

“Remarkable. . . . A Jury of Her Peers does an enormous service, houses a drop-dead reading list and gives the reader a fluid framework for the great (much of it still undiscovered) wealth of writing by women in this country.”

— The Los Angeles Times

“Impressively researched. . . . Generous, thought-provoking. . . . [Showalter is] less polarized and more nuanced than other feminist critics of her generation . . . She is a lively and incisive guide, the perfect Virgil for our quest.” —The Washington Post

“Enlightening . . . the book may be dipped into at any chapter with much reward . . . . Showalter captures so well, often in just a few paragraphs, the image of the women she writes about. . . . Reading A Jury of Her Peers is not only an education in literary history, it is eminently satisfactory intellectual nourishment. 4 out of 4 stars.” —Free Press

“[A] vast democratic volume . . . . Vivid . . . extremely readable and enlightening . . . . Her short, incisive biographies offer a glimpse into the exotic travails of the past and the eternal concerns of female experience . . . [A] ranging, inclusive history . . . . likely to become an important and valuable resource for anyone interested in women’s history.” —The New York Times Book Review

“A delicious compendium, a book that belongs in literature courses, of course, but also in writerly libraries and in the hands of anyone who enjoys reading about writers’ lives. . . . Essential.” —Barnes & Noble Review

“Clear-sighted, ambitious . . . minutely researched and rich with opinion, anecdotes, samples, and interpretation. . . . Monumental.” —Elle

“Absorbing. . . . excellent. . . . insightful. . . . the prose is so good that the 500-plus-page book also works as an absorbing cover-to-cover read. . . . Showalter does not try to force any of these writers into uncomfortable slots in any kind of artificial female pantheon. These writers are all individuals, and Showalter treats them as such.” —The Christian Science Monitor

“Elaine Showalter has delivered the first literary history of American women ever published, and the result is a riveting journey with scarcely a becalmed page . . . rich, readable . . . an immensely valuable work . . . vibrant regardless of where one dips in.” —The Seattle Times

“Accessible and readable. Brimming with wit and insight . . . . This monumental book will greatly enrich our understanding of American literary history and our culture.” —Tuscon Citizen, Recommended New Title

“Showalter may have written the perfect book-group book: Not only is it fascinating on its own, but it also opens up possibilities for decades of further reading. . . . Like a raucous party, with some squabbling going on in the darker corners. . . . Showalter’s prose is lively, and she has no problem expressing her opinions” —The Columbus Dispatch

“A breathtaking overview of the intersections of gender and genre in American letters. . . . With its frank assessments, impressive research and expansive scope, A Jury of Her Peers belongs on the shelf of any reader interested in the development of women’s writing in America.” —Ms. Magazine

Cuprins

Introduction

1. A New Literature Springs Up in the New World

2. Revolution: Women’s Rights and Women’s Writing

3. Their Native Land

4. Finding a Form

5. Masterpieces and Mass Markets

6. Slavery, Race, and Women’s Writing

7. The Civil War

8. The Coming Woman

9. American Sibyls

10. New Women

11. The Golden Morrow

12. Against Women’s Writing: Wharton and Cather

13. You Might as Well Live

14. The Great Depression

15. The 1940s: World War II and After

16. The 1950s: Three Faces of Eve

17. The 1960s: Live or Die

18. The 1970s: The Will to Change

19. The 1980s: On the Jury

20. The 1990s: Anything She Wants

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Writers Discussed in the Book

Introduction

Susan Glaspell

Lydia Maria Child

Catherine Fenimore Woolson

Mary Austin

Zona Gale

Elizabeth Roberts

Julia Ward Howe

Pauline Hopkins

Nella Larsen

Emily Dickinson

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Gwendolyn Brooks

Edith Wharton

Willa Cather

Chapter 1: The 1600s

Anne Bradstreet

Mary Rowlandson

Chapter 2: The 1700s

Sarah Kemble Knight

Jane Coleman Turell

Elizabeth Magawley

Phillis Wheatley

Judith Sargent Murray

Mercy Otis Warren

Susanna Rowson

Anna Steele

Anna Young Smith

Sarah Wentworth Morton

Abigail Adams

Sukey Vickery

Hannah Webster Foster

Sally Sayward Barrell

Keating Wood

Tabitha Tenney

Chapter 3: 1820s-1830s

Lydia Maria Child

Sarah J. Hale

Mary Griffin

Catherine Maria Sedgwick

Caroline Kirkland

Chapter 4: 1840s

Margaret Fuller

Caroline May

Alice Cary

Frances Sargent Osgood

Maria Gowen Brooks

Elizabeth Oakes-Smith

Lydia HuntleySigourney

Anna Cora Mowatt

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Chapter 5: 1850s, Part I

Julia Ward Howe

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Miriam Berry Whicher

Susan Warner

Grace Greenwood

Hannah Gardner Creamer

Caroline Chesebro’

Anna Warner

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Caroline Hentz

E.D.E.N. Southworth

“Fanny Fern” (Sarah Peyton Willis)

Laura Curtis Bullard

Lillie Devereaux Blake

Alice Cary

H. Marion Stephenson

Mary Virginia Hawes Terhune

Augusta Jane Evans

Harriet Prescott Spofford

Chapter 6: 1850s, Part II

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Mary Eastman

Caroline Hentz

Frances Watkins Harper

Lydia Maria Child

Harriet Jacobs

Harriet E. Wilson

“Hannah Crafts”

Chapter 7:

The Civil War

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Lucy Larcom

Caroline A. Mason

Julia LeGrand

Louisa May Alcott

E.D.E.N. Southworth

Augusta Jane Evans

Rebecca Harding Davis

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Elizabeth Barstow Stoddard

Emily Dickinson

Mary Terhune

Martha Finley

Mary Abigail Dodge

Chapter 8: The 1870s

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Julia Ward Howe

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Gail Hamilton

Alice Cary

Marietta Holley

Susan B. Anthony

Lillie Devereaux Blake

Sherwood Bonner

Chapter 9: The 1880s

Constance Fenimore Woolson

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Emma Lazarus

Rose Terry Cooke

Sarah Orne Jewett

Willa Cather

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman

Mary Noailles Murfree

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Helen Fiske Hunt Jackson

Chapter 10: The 1890s

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Gertrude Atherton

Kate Chopin

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Louise Imogen Guiney

Ella Wheeler Wilcox

Elizabeth Robins

Edith Wharton

Frances Harper

Pauline Hopkins

Eveleen Mason

Lois Waisbrooker

Alice Ilgenfritz Jones

Ella Merchant

Eliza J. Nicholson

Elizabeth Gilmer

Julia Ward Howe

Maud Howe

Grace King

Louisa May Alcott

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Helen Hunt Jackson

Mary Wilkins Freeman

Ellen Glasgow

Helen Gray Cone

Chapter 11: The 1900s

Margaret Fuller

Mary Johnston

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Francis Whiting Halsey

Edith Wharton

Gertrude Atherton

Mary Hunter Austin

Gertrude Stein

Hilda Doolittle

Marianne Moore

Amy Lowell

Mary Antin

Gertrude Simmons Bonnin

Edith Maud Easton

Elizabeth Robins

Rachel Crothers

Susan Glaspell

Kate Chopin

Willa Cather

Kate Douglas Wiggin

Geneva Stratton-Porter

Jean Webster

Eleanor H. Porter

Chapter 12: The 1910s

Edith Wharton

Willa Cather

Margaret Fuller

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Kate Chopin

Chapter 13: The 1920s

Sylvia Plath

Gwendolyn Brooks

Josephine Herbst

Ellen Glasgow

Elizabeth Madox Roberts

Edith Summers Kelley

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Gertrude Stein

Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)

Elinor Wylie

Amy Lowell

Genevieve Taggard

Dorothy Parker

Louise Bogan

Sara Teasdale

Louisa May Alcott

Genevieve Taggard

Mina Loy

Dorothy Dunbar Bromley

Nella Larsen

Josephine Herbst

Katherine Anne Porter

Sophie Treadwell

Zoe Akins

Zona Gale

Dorothy Canfield Fisher

Pearl Buck

Willa Cather

Anzia Yezierska

Emily Dickinson

Jessie Fauset

Kate Chopin

Chapter 14: The 1930s

Meridel Le Sueur

Susan Glaspell

Willa Cather

Emily Dickinson

Fanny Hurst

Katherine Anne Porter

Zoe Akins

Dorothy Parker

Tess Slesinger

Lillian Hellman

Clare Boothe

Pearl Buck

Margaret Mitchell

Edith Wharton

Jessie Fauset

Nella Larsen

Margaret Walker

Muriel Rukeyser

Sara Teasdale

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Martha Gellhorn

Josephine Herbst

Tillie Olsen

Louise Bogan

Djuna Barnes

Susan Sontag

Harriet Sohmers

Mary Wilkins Freeman

Zora Neale Hurston

Chapter 15: The 1940s

Louise Bogan

Jane Cooper

Margaret Walker

Gwendolyn Brooks

Sylvia Plath

Alice Bradley Sheldon

Martha Gellhorn

Hisaye Yamamoto

Eudora Welty

Carson McCullers

Flannery O’Connor

Katherine Anne Porter

Agnes Smedley

Jean Stafford

Margaret Walker

Harper Lee

Ann Petry

Dorothy West

Sally Benson

Ayn Rand

Betty Smith

Betty Macdonald

Jessamyn West

Laura Z. Hobson

Kathleen Winsor

Fay Kanin

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Chapter 16: The 1950s

Carson McCullers

Shirley Jackson

Sylvia Plath

Gwendolyn Brooks

Flannery O’Connor

Adrienne Rich

Joyce Carol Oates

Kathleen Norris

Fannie Hurst

Jessie Fauset

Nella Larsen

Harriette Simpson Arnow

Mary McCarthy

Jean Stafford

Grace Metalious

Leonie Adams

Babette Deutsch

Muriel Rukeyser

May Swenson

Mona Van Duyn

Jean Garrigue

Barbara Howe

Anne Sexton

Marianne Moore

Louise Bogan

Elizabeth Bishop

Patricia Highsmith

Ann Weldy

Lorraine Hansberry

Chapter 17: The 1960s

Gwendolyn Brooks

Anne Sexton

Denise Levertov

Muriel Rukeyser

Harper Lee

Katherine Anne Porter

Mary McCarthy

Louise Bogan

Joyce Carol Oates

S. E. Hinton

Adrienne Rich

Maxine Kumin

Tillie Olsen

Sara Teasdale

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Betty Friedan

Sarah Orne Jewett

Jean Stafford

Chapter 18: The 1970s

Adrienne Rich

Michelle Cliff

Kate Millet

Robin Morgan

Shulamith Firestone

Toni Cade Bambara

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Toni Morrison

Erica Jong

Nikki Giovanni

Maya Angelou

Audre Lord

Ntozake Shange

Alice Walker

Zora Neale Hurston

Nella Larsen

Diane Johnson

Gail Godwin

Judith Rossner

Lois Gould

Joyce Carol Oates

Dorothy Bryant

Ursula LeGuin

Joanna Russ

Marge Piercy

James Tiptree, Jr./ Alice Bradley Sheldon

Willa Cather

Vonda N. McIntyre

Chelsea Quinn Yarboro

Joanna Russ

Grace Paley

Maxine Hong Kingston

Anne Tyler

Joan Didion

Susan Sontag

Cynthia Ozick

Chapter 19: The 1980s

Sharon Olds

Alice Walker

Phillis Wheatley

Joyce Carol Oates

Elizabeth Bishop

Cynthia Ozick

Ursula LeGuin

Beth Henley

Marsha Norman

Wendy Wasserstein

Sara Paretsky

Sue Grafton

Patricia Cornwell

Toni Morrison

Louise Erdrich

Alice Walker

Marilynne Robinson

Gloria Naylor

Sandra Cisneros

Amy Tan

Amy Hempel

Bharati Mukherjee

Mary Robison

Jayne Anne Phillips

Ann Beattie

Bobbie Ann Mason

Gloria Naylor

Chapter 20: The 1990s

Toni Morrison

Lynn Hejinian

Marilyn Hacker

Sharon Olds

Louise Glück

Anne Carson

Jorie Graham

Rita Dove

Jodie Picoult

Jennifer Weiner

Terry McMillan

Susannah Moore

A. M. Homes

Joyce Carol Oates

Susan Sontag

Susan Choi

Wendy Wasserstein

Joanne Dobson

Gish Jen

Jane Smiley

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Sena Jeter Naslund

Annie Proulx

Anne Bradstreet

Mary Rowlandson

1. A New Literature Springs Up in the New World

2. Revolution: Women’s Rights and Women’s Writing

3. Their Native Land

4. Finding a Form

5. Masterpieces and Mass Markets

6. Slavery, Race, and Women’s Writing

7. The Civil War

8. The Coming Woman

9. American Sibyls

10. New Women

11. The Golden Morrow

12. Against Women’s Writing: Wharton and Cather

13. You Might as Well Live

14. The Great Depression

15. The 1940s: World War II and After

16. The 1950s: Three Faces of Eve

17. The 1960s: Live or Die

18. The 1970s: The Will to Change

19. The 1980s: On the Jury

20. The 1990s: Anything She Wants

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Writers Discussed in the Book

Introduction

Susan Glaspell

Lydia Maria Child

Catherine Fenimore Woolson

Mary Austin

Zona Gale

Elizabeth Roberts

Julia Ward Howe

Pauline Hopkins

Nella Larsen

Emily Dickinson

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Gwendolyn Brooks

Edith Wharton

Willa Cather

Chapter 1: The 1600s

Anne Bradstreet

Mary Rowlandson

Chapter 2: The 1700s

Sarah Kemble Knight

Jane Coleman Turell

Elizabeth Magawley

Phillis Wheatley

Judith Sargent Murray

Mercy Otis Warren

Susanna Rowson

Anna Steele

Anna Young Smith

Sarah Wentworth Morton

Abigail Adams

Sukey Vickery

Hannah Webster Foster

Sally Sayward Barrell

Keating Wood

Tabitha Tenney

Chapter 3: 1820s-1830s

Lydia Maria Child

Sarah J. Hale

Mary Griffin

Catherine Maria Sedgwick

Caroline Kirkland

Chapter 4: 1840s

Margaret Fuller

Caroline May

Alice Cary

Frances Sargent Osgood

Maria Gowen Brooks

Elizabeth Oakes-Smith

Lydia HuntleySigourney

Anna Cora Mowatt

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Chapter 5: 1850s, Part I

Julia Ward Howe

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Miriam Berry Whicher

Susan Warner

Grace Greenwood

Hannah Gardner Creamer

Caroline Chesebro’

Anna Warner

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Caroline Hentz

E.D.E.N. Southworth

“Fanny Fern” (Sarah Peyton Willis)

Laura Curtis Bullard

Lillie Devereaux Blake

Alice Cary

H. Marion Stephenson

Mary Virginia Hawes Terhune

Augusta Jane Evans

Harriet Prescott Spofford

Chapter 6: 1850s, Part II

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Mary Eastman

Caroline Hentz

Frances Watkins Harper

Lydia Maria Child

Harriet Jacobs

Harriet E. Wilson

“Hannah Crafts”

Chapter 7:

The Civil War

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Lucy Larcom

Caroline A. Mason

Julia LeGrand

Louisa May Alcott

E.D.E.N. Southworth

Augusta Jane Evans

Rebecca Harding Davis

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Elizabeth Barstow Stoddard

Emily Dickinson

Mary Terhune

Martha Finley

Mary Abigail Dodge

Chapter 8: The 1870s

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Julia Ward Howe

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Gail Hamilton

Alice Cary

Marietta Holley

Susan B. Anthony

Lillie Devereaux Blake

Sherwood Bonner

Chapter 9: The 1880s

Constance Fenimore Woolson

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Emma Lazarus

Rose Terry Cooke

Sarah Orne Jewett

Willa Cather

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman

Mary Noailles Murfree

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Helen Fiske Hunt Jackson

Chapter 10: The 1890s

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Gertrude Atherton

Kate Chopin

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Louise Imogen Guiney

Ella Wheeler Wilcox

Elizabeth Robins

Edith Wharton

Frances Harper

Pauline Hopkins

Eveleen Mason

Lois Waisbrooker

Alice Ilgenfritz Jones

Ella Merchant

Eliza J. Nicholson

Elizabeth Gilmer

Julia Ward Howe

Maud Howe

Grace King

Louisa May Alcott

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Helen Hunt Jackson

Mary Wilkins Freeman

Ellen Glasgow

Helen Gray Cone

Chapter 11: The 1900s

Margaret Fuller

Mary Johnston

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Francis Whiting Halsey

Edith Wharton

Gertrude Atherton

Mary Hunter Austin

Gertrude Stein

Hilda Doolittle

Marianne Moore

Amy Lowell

Mary Antin

Gertrude Simmons Bonnin

Edith Maud Easton

Elizabeth Robins

Rachel Crothers

Susan Glaspell

Kate Chopin

Willa Cather

Kate Douglas Wiggin

Geneva Stratton-Porter

Jean Webster

Eleanor H. Porter

Chapter 12: The 1910s

Edith Wharton

Willa Cather

Margaret Fuller

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Kate Chopin

Chapter 13: The 1920s

Sylvia Plath

Gwendolyn Brooks

Josephine Herbst

Ellen Glasgow

Elizabeth Madox Roberts

Edith Summers Kelley

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Gertrude Stein

Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)

Elinor Wylie

Amy Lowell

Genevieve Taggard

Dorothy Parker

Louise Bogan

Sara Teasdale

Louisa May Alcott

Genevieve Taggard

Mina Loy

Dorothy Dunbar Bromley

Nella Larsen

Josephine Herbst

Katherine Anne Porter

Sophie Treadwell

Zoe Akins

Zona Gale

Dorothy Canfield Fisher

Pearl Buck

Willa Cather

Anzia Yezierska

Emily Dickinson

Jessie Fauset

Kate Chopin

Chapter 14: The 1930s

Meridel Le Sueur

Susan Glaspell

Willa Cather

Emily Dickinson

Fanny Hurst

Katherine Anne Porter

Zoe Akins

Dorothy Parker

Tess Slesinger

Lillian Hellman

Clare Boothe

Pearl Buck

Margaret Mitchell

Edith Wharton

Jessie Fauset

Nella Larsen

Margaret Walker

Muriel Rukeyser

Sara Teasdale

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Martha Gellhorn

Josephine Herbst

Tillie Olsen

Louise Bogan

Djuna Barnes

Susan Sontag

Harriet Sohmers

Mary Wilkins Freeman

Zora Neale Hurston

Chapter 15: The 1940s

Louise Bogan

Jane Cooper

Margaret Walker

Gwendolyn Brooks

Sylvia Plath

Alice Bradley Sheldon

Martha Gellhorn

Hisaye Yamamoto

Eudora Welty

Carson McCullers

Flannery O’Connor

Katherine Anne Porter

Agnes Smedley

Jean Stafford

Margaret Walker

Harper Lee

Ann Petry

Dorothy West

Sally Benson

Ayn Rand

Betty Smith

Betty Macdonald

Jessamyn West

Laura Z. Hobson

Kathleen Winsor

Fay Kanin

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Chapter 16: The 1950s

Carson McCullers

Shirley Jackson

Sylvia Plath

Gwendolyn Brooks

Flannery O’Connor

Adrienne Rich

Joyce Carol Oates

Kathleen Norris

Fannie Hurst

Jessie Fauset

Nella Larsen

Harriette Simpson Arnow

Mary McCarthy

Jean Stafford

Grace Metalious

Leonie Adams

Babette Deutsch

Muriel Rukeyser

May Swenson

Mona Van Duyn

Jean Garrigue

Barbara Howe

Anne Sexton

Marianne Moore

Louise Bogan

Elizabeth Bishop

Patricia Highsmith

Ann Weldy

Lorraine Hansberry

Chapter 17: The 1960s

Gwendolyn Brooks

Anne Sexton

Denise Levertov

Muriel Rukeyser

Harper Lee

Katherine Anne Porter

Mary McCarthy

Louise Bogan

Joyce Carol Oates

S. E. Hinton

Adrienne Rich

Maxine Kumin

Tillie Olsen

Sara Teasdale

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Betty Friedan

Sarah Orne Jewett

Jean Stafford

Chapter 18: The 1970s

Adrienne Rich

Michelle Cliff

Kate Millet

Robin Morgan

Shulamith Firestone

Toni Cade Bambara

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Toni Morrison

Erica Jong

Nikki Giovanni

Maya Angelou

Audre Lord

Ntozake Shange

Alice Walker

Zora Neale Hurston

Nella Larsen

Diane Johnson

Gail Godwin

Judith Rossner

Lois Gould

Joyce Carol Oates

Dorothy Bryant

Ursula LeGuin

Joanna Russ

Marge Piercy

James Tiptree, Jr./ Alice Bradley Sheldon

Willa Cather

Vonda N. McIntyre

Chelsea Quinn Yarboro

Joanna Russ

Grace Paley

Maxine Hong Kingston

Anne Tyler

Joan Didion

Susan Sontag

Cynthia Ozick

Chapter 19: The 1980s

Sharon Olds

Alice Walker

Phillis Wheatley

Joyce Carol Oates

Elizabeth Bishop

Cynthia Ozick

Ursula LeGuin

Beth Henley

Marsha Norman

Wendy Wasserstein

Sara Paretsky

Sue Grafton

Patricia Cornwell

Toni Morrison

Louise Erdrich

Alice Walker

Marilynne Robinson

Gloria Naylor

Sandra Cisneros

Amy Tan

Amy Hempel

Bharati Mukherjee

Mary Robison

Jayne Anne Phillips

Ann Beattie

Bobbie Ann Mason

Gloria Naylor

Chapter 20: The 1990s

Toni Morrison

Lynn Hejinian

Marilyn Hacker

Sharon Olds

Louise Glück

Anne Carson

Jorie Graham

Rita Dove

Jodie Picoult

Jennifer Weiner

Terry McMillan

Susannah Moore

A. M. Homes

Joyce Carol Oates

Susan Sontag

Susan Choi

Wendy Wasserstein

Joanne Dobson

Gish Jen

Jane Smiley

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Sena Jeter Naslund

Annie Proulx

Anne Bradstreet

Mary Rowlandson