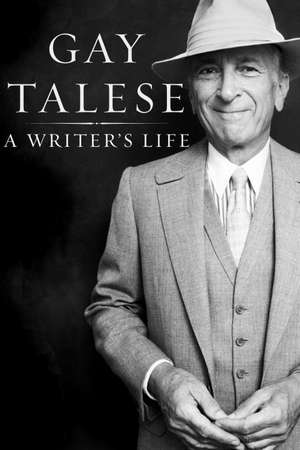

A Writer's Life

Autor Gay Taleseen Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 mar 2006

How has Talese found his subjects? What has stimulated, blocked, or inspired his writing? Here are his amateur beginnings on his college newspaper; his professional climb at The New York Times; his desire to write on a larger canvas, which led him to magazine writing at Esquire and then to books. We see his involvement with issues of race from his student days in the Deep South to a recent interracial wedding in Selma, Alabama, where he once covered the fierce struggle for civil rights. Here are his reflections on the changing American sexual mores he has written about over the last fifty years, and a striking look at the lives—and their meaning—of Lorena and John Bobbitt. He takes us behind the scenes of his legendary profile of Frank Sinatra, his writings about Joe DiMaggio and heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson, and his interview with the head of a Mafia family.

But he is at his most poignant in talking about the ordinary men and women whose stories led to his most memorable work. In remarkable fashion, he traces the history of a single restaurant location in New York, creating an ethnic mosaic of one restaurateur after the other whose dreams were dashed while a successor’s were born. And as he delves into the life of a young female Chinese soccer player, we see his consuming interest in the world in its latest manifestation.

In these and other recollections and stories, Talese gives us a fascinating picture of both the serendipity and meticulousness involved in getting a story. He makes clear that every one of us represents a good one, if a writer has the curiosity to know it, the diligence to pursue it, and the desire to get it right.

Candid, humorous, deeply impassioned—a dazzling book about the nature of writing in one man’s life, and of writing itself.

Preț: 156.18 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 234

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.90€ • 30.75$ • 24.80£

29.90€ • 30.75$ • 24.80£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679410966

ISBN-10: 0679410961

Pagini: 429

Dimensiuni: 169 x 239 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.79 kg

Editura: ALFRED A KNOPF

ISBN-10: 0679410961

Pagini: 429

Dimensiuni: 169 x 239 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.79 kg

Editura: ALFRED A KNOPF

Notă biografică

Gay Talese was a reporter for The New York Times from 1956 to 1965. Since then he has written for the Times, Esquire, The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, and other national publications. He is the author of eleven books. He lives with his wife, Nan, in New York City.

Extras

1

I am not now, nor have I ever been, fond of the game of soccer. Part of the reason is probably attributable to my age and the fact that when I was growing up along the southern shore of New Jersey a half century ago, the sport was virtually unknown to Americans, except to those of foreign birth. And even though my father was foreign-born—he was a dandified but dour custom tailor from a Calabrian village in southern Italy who became a United States citizen in the mid-1920s—his references to me about soccer were associated with his boyhood conflicts over the game, and his desire to play it in the afternoons with his school friends in an Italian courtyard instead of merely watching it being played as he sat sewing at the rear window of the nearby shop to which he was apprenticed; yet, as he often reminded me, he knew even then that these young male performers (including his less dutiful brothers and cousins) were wasting their time and their future lives as they kicked the ball back and forth when they should have been learning a worthy craft and anticipating the high cost of a ticket to immigrant prosperity in America! But no, he continued in his tireless way of warning me, they idled away their afternoons playing soccer in the courtyard as they would later play it behind the barbed wire of the Allied prisoner of war camp in North Africa to which they were sent (they who were not killed or crippled in combat) following their surrender in 1942 as infantrymen in Mussolini's losing army. Occasionally they sent letters to my father describing their confinement; and one day near the end of World War II he put aside the mail and told me in a tone of voice that I prefer to believe was more sad than sarcastic, "They're still playing soccer!"

The World Cup soccer finale between the women of China and the United States, held on July 10, 1999, in Pasadena, California, before 90,185 spectators in the Rose Bowl (the largest turnout for any women's sporting contest in history), was scheduled to be televised to nearly 200 million people around the world. The live telecast that would begin on this Saturday afternoon in California at 12:30 would be seen in New York at 3:30 p.m. and in China at 4:30 a.m. on Sunday. I had not planned to watch the match. On this particular Saturday in New York I had already made arrangements for midday doubles in Central Park with a few old pals who shared my faulty recollections on how well we once played tennis.

Before leaving for Central Park I thought I'd tune in to the baseball game that started at 1:15, featuring the New York Mets and my cherished Yankees. Irrespective of the weary, though at times wavering, counsel of my leisure-deprived and now deceased father, the Yankees had captured my heart and enslaved me forever as a fan back in February 1944 when, prompted by wartime gas rationing and its limiting effect on travel, the team shifted its traditional spring training site from Saint Petersburg, Florida, to a less warm but more centralized, if rickety, rust-railed ballpark near the Atlantic City airport, within truancy range of my school. From then on, through war and peace and extending through the careers of Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle to the turn-of-the-century stardom of such newcomers as the shortstop Derek Jeter and the relief pitcher Mariano Rivera, I have reveled in the New York Yankees' triumphs and lamented their losses, and on this July Saturday in 1999, I was counting on them to divert me from several weeks of weak hitting at my typewriter.

I needed to relax, to put aside my book for a while, I decided; and I readily accepted my wife's suggestion, expressed days earlier, that we spend this weekend quietly in New York. Our two daughters and their boyfriends would be driving down to the Jersey shore to make use of our summer home, which we had bought near my parents' place thirty years ago, following the birth of our second daughter; on Saturday evening my vigorous ninety-two-year-old widowed mother was looking forward to taking her granddaughters and their boyfriends to dine with her at the Taj Mahal casino on the Atlantic City boardwalk, where she liked to have coffee and dessert in the lounge while feeding the slot machines.

During the previous month my lovely wife and I had celebrated our fortieth wedding anniversary, and I hope I will not be perceived as unromantic if I suggest that this lengthy relationship has succeeded in part because we have regularly lived and worked apart—I as a researching writer of nonfiction who is often on the road, and she as an editor and publisher who through the years has carefully avoided affiliating herself with firms to which I am contractually connected. But when we are together under the same roof, sharing what I shall take the liberty of calling a harmonious and happy coexistence that began in the mid-1950s with a courtship kindled in a cold-water flat in Greenwich Village and then moved uptown and expanded with children in a brownstone still owned and occupied by the two of us (two spry senior citizens determined not to die on a cruise ship), I must admit that I have frequently taken advantage of my wife's domestic presence as a literary professional, seeking her opinion not only on what I am thinking of writing but also on what I have written; and while her responses occasionally differ from those expressed later by my acknowledged editor, I consider myself more blessed than burdened when I have varying views to choose from, finding this far preferable to the lack of editorial access that many of my writer friends often complain about. But to writers who bemoan their lives of neglect and loneliness, let me say this: When one's own work is not going well, having a wife who is an editor can be even more demoralizing, particularly during those at-home weekends and nights when she is avidly reading other people's words while reclining on our marital bed under a crinkling spread of manuscript pages that lie atop our designer duvet or between the sheets, which in due time she will shake out in order to reclaim the pages and stack them neatly on her bedside table before turning out the lights and possibly dreaming of when the pages will be transformed into a beautifully bound, critically acclaimed book.

In any event, on this weekend when we decided (she decided) to remain in New York, and while she was upstairs editing the chapters of a manuscript we had slept with on Friday night, I was downstairs watching the Yankee-Mets game (the Yankees took a quick 2-0 lead on Paul O'Neill's first-inning homer, following Bernie Williams's single). Between innings I was thinking ahead to my tennis match and reminding myself that I must toss the ball higher when serving and seize every opportunity to get to the net.

I had been introduced to tennis by my gym teacher during my junior year in high school, and even though our school did not then field a tennis team, I played the game as often as I could during lunchtime recess because I could play it better than the ungainly classmates whom I selected as opponents and who also served under me as staff members on the student newspaper. That I never achieved distinction while competing on a varsity level in a major sport (football, basketball, baseball, or track) did not upset me because our school's teams were mediocre in these sports. Besides which, as the players' chronicler and potential critic (in addition to working on the school paper I wrote about sports as well as classroom activities in my extracurricular role as scholastic correspondent for my hometown weekly and the Atlantic City daily), I was suddenly experiencing the dubious eminence of being a journalist, of having my callow character and identity boosted, if not enhanced, by my bylined articles and the stamp-size photo of myself that appeared above my school-page column in the town weekly, to say nothing of the many privileges that were now mine to select, such as to travel to out-of-town games on the team bus in a reserved seat behind the coach, or to catch a ride later in a chrome-embellished Buick coup driven by the athletic director's pretty wife.

As ineffectual as the players usually were, fumbling the football constantly, striking out habitually, and missing most of their foul shots, I never humiliated them in print. I invariably found ways to describe delicately each team defeat, each individual inadequacy. I seemed to possess in my writing a precocious flare for rhetoric and circumlocution long before I could accurately spell either word. My approach to journalism was strongly influenced throughout my high school years by a florid novelist named Frank Yerby, a Georgia-born black man who later settled in Spain and wrote prolifically about bejeweled and crinoline-skirted women of such erotic excess that, were it not for Yerby's illusory prose style, which somehow obfuscated what to me was breathtakingly obscene, his books would have been censored throughout the United States, and I would have been denied the opportunity to request each and every one of them sheepishly from the proprietress of our town library, and furthermore would not then have tried to emulate Yerby's palliative way with words in my attempts to cloak and cover up the misdeeds and deficiencies of our school's athletes in my newspaper articles.

While my evasive and roundabout reportage might be ascribed to my desire to maintain friendly relations with the athletes and encourage their continuing participation in interviews, I believe that practical matters had far less to do with it than did my own youthful identity with disappointment and the fact that, except for my skill in writing pieces that softened the harsh reality of the truth, I could do nothing exceptionally well. The grades I received from teachers in elementary as well as high school consistently placed me in the lower half of my class. Next to chemistry and math, English was my worst subject. In 1949, I was rejected by the two dozen colleges that I applied to in my native state of New Jersey and neighboring Pennsylvania and New York. That I was accepted into the freshman class at the University of Alabama was entirely the result of my father's appeals to a magnanimous Birmingham-born physician who practiced in our town and wore suits superbly designed and tailored by my father, and by this physician's own subsequent petitions on my behalf to his onetime classmate and everlasting friend then serving as Alabama's dean of admissions.

My main achievements during my four years on the Alabama campus were being appointed sports editor of the college weekly and the popularity I gained through my authorship of a column called "Sports Gay-zing," which, often blending humor with solicitousness and a veiled viewpoint, made the best of perhaps some of the worst displays of athleticism in the school's proud history. Even the Alabama football team, long accustomed to justifying its national reputation as a perennial top-ten powerhouse, suffered when I was a student through many days sadder than any since the Civil War. While gridiron glory would be restored after 1958 with the arrival of the now legendary coach Paul "Bear" Bryant, the football schedule during my time was more often than not the cause of a statewide weekend wake; and the coach of the team, a New Englander named Harold "Red" Drew, was routinely burned in effigy on Saturday nights in the center of the campus by raucous crowds of fraternity men and their girlfriends from sororities in which the pledges had spent the afternoon sewing together sackcloth body-size figures with bug eyes and fat rouge-smeared faces that were supposed to replicate the features of Red Drew.

Although Drew never complained about any of this to me or my staff, I began to feel very sorry for him, and in our sports section I always tried to put a positive spin on his downward-spiraling career. In one of my columns I emphasized the valor he had shown while serving his country as a naval officer in World War I, highlighting an occasion on which he had jumped two thousand feet from a blimp into the Gulf of Mexico. This leap in 1917, when Drew was an ensign, established him as the first parachute jumper in naval history, or so I wrote after getting the information from a yellowed newspaper clipping that was pasted in an old scrapbook lent to me by the coach's wife. I also illustrated what I wrote with a World War I–vintage photograph showing a lean and broad-shouldered Ensign Drew standing in front of a double-winged navy fighter plane at a base in the Panama Canal, wearing jodhpurs and knee-high boots and an officer's cap decorated with an insignia and bearing a peak that shaded his eyes from the sun without concealing an understated smile that I hoped my readers would see as the mark of a modest and fearless warrior—thinking, naïvely, that this would arouse their patriotism and extinguish a few of the nighttime torches that they raised in vilifying Coach Drew and also at times his venerable assistant, Henry "Hank" Crisp, who specialized in directing Alabama's porous front line of defense.

In yet another futile attempt on my part to divert the fans from such disastrous performances as were customarily presented throughout such seasons as 1951, for example, when the team lost six out of eleven games, I dramatized the tragedy partly with words lifted from Shakespeare:

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis Drew or Crisp who must suffer the

slings and arrows of outrageous blocking, or to take

arms against football writers, and by opposing end

them?

To win: to lose: to get wrecked, routed, o'erwhelmed

and consumed by prissy Villanova. . . .

Ah, to sleep, for in that sleep of death one dreams

of our opponents who plunged and fled with leather football

under arm, around, under, and over Bama walls. . . .

I left Red Drew to his own fate following my graduation in the spring of 1953. A year later I read that he had resigned in the wake of his team's 4-5-2 record, which might have been considered outstanding if compared with the accomplishments of his successor, J. B. "Ears" Whitworth, who in 1955 lost ten games without winning even one. During these two years I did not return to the campus to witness any of these engagements, being assigned for my military service to an armored unit in Kentucky much of the time, and then stationed with that unit in Germany for part of the time, until my discharge in the winter of 1955 enabled me to accept a reportorial job in the sports department of the New York Times.

I am not now, nor have I ever been, fond of the game of soccer. Part of the reason is probably attributable to my age and the fact that when I was growing up along the southern shore of New Jersey a half century ago, the sport was virtually unknown to Americans, except to those of foreign birth. And even though my father was foreign-born—he was a dandified but dour custom tailor from a Calabrian village in southern Italy who became a United States citizen in the mid-1920s—his references to me about soccer were associated with his boyhood conflicts over the game, and his desire to play it in the afternoons with his school friends in an Italian courtyard instead of merely watching it being played as he sat sewing at the rear window of the nearby shop to which he was apprenticed; yet, as he often reminded me, he knew even then that these young male performers (including his less dutiful brothers and cousins) were wasting their time and their future lives as they kicked the ball back and forth when they should have been learning a worthy craft and anticipating the high cost of a ticket to immigrant prosperity in America! But no, he continued in his tireless way of warning me, they idled away their afternoons playing soccer in the courtyard as they would later play it behind the barbed wire of the Allied prisoner of war camp in North Africa to which they were sent (they who were not killed or crippled in combat) following their surrender in 1942 as infantrymen in Mussolini's losing army. Occasionally they sent letters to my father describing their confinement; and one day near the end of World War II he put aside the mail and told me in a tone of voice that I prefer to believe was more sad than sarcastic, "They're still playing soccer!"

The World Cup soccer finale between the women of China and the United States, held on July 10, 1999, in Pasadena, California, before 90,185 spectators in the Rose Bowl (the largest turnout for any women's sporting contest in history), was scheduled to be televised to nearly 200 million people around the world. The live telecast that would begin on this Saturday afternoon in California at 12:30 would be seen in New York at 3:30 p.m. and in China at 4:30 a.m. on Sunday. I had not planned to watch the match. On this particular Saturday in New York I had already made arrangements for midday doubles in Central Park with a few old pals who shared my faulty recollections on how well we once played tennis.

Before leaving for Central Park I thought I'd tune in to the baseball game that started at 1:15, featuring the New York Mets and my cherished Yankees. Irrespective of the weary, though at times wavering, counsel of my leisure-deprived and now deceased father, the Yankees had captured my heart and enslaved me forever as a fan back in February 1944 when, prompted by wartime gas rationing and its limiting effect on travel, the team shifted its traditional spring training site from Saint Petersburg, Florida, to a less warm but more centralized, if rickety, rust-railed ballpark near the Atlantic City airport, within truancy range of my school. From then on, through war and peace and extending through the careers of Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle to the turn-of-the-century stardom of such newcomers as the shortstop Derek Jeter and the relief pitcher Mariano Rivera, I have reveled in the New York Yankees' triumphs and lamented their losses, and on this July Saturday in 1999, I was counting on them to divert me from several weeks of weak hitting at my typewriter.

I needed to relax, to put aside my book for a while, I decided; and I readily accepted my wife's suggestion, expressed days earlier, that we spend this weekend quietly in New York. Our two daughters and their boyfriends would be driving down to the Jersey shore to make use of our summer home, which we had bought near my parents' place thirty years ago, following the birth of our second daughter; on Saturday evening my vigorous ninety-two-year-old widowed mother was looking forward to taking her granddaughters and their boyfriends to dine with her at the Taj Mahal casino on the Atlantic City boardwalk, where she liked to have coffee and dessert in the lounge while feeding the slot machines.

During the previous month my lovely wife and I had celebrated our fortieth wedding anniversary, and I hope I will not be perceived as unromantic if I suggest that this lengthy relationship has succeeded in part because we have regularly lived and worked apart—I as a researching writer of nonfiction who is often on the road, and she as an editor and publisher who through the years has carefully avoided affiliating herself with firms to which I am contractually connected. But when we are together under the same roof, sharing what I shall take the liberty of calling a harmonious and happy coexistence that began in the mid-1950s with a courtship kindled in a cold-water flat in Greenwich Village and then moved uptown and expanded with children in a brownstone still owned and occupied by the two of us (two spry senior citizens determined not to die on a cruise ship), I must admit that I have frequently taken advantage of my wife's domestic presence as a literary professional, seeking her opinion not only on what I am thinking of writing but also on what I have written; and while her responses occasionally differ from those expressed later by my acknowledged editor, I consider myself more blessed than burdened when I have varying views to choose from, finding this far preferable to the lack of editorial access that many of my writer friends often complain about. But to writers who bemoan their lives of neglect and loneliness, let me say this: When one's own work is not going well, having a wife who is an editor can be even more demoralizing, particularly during those at-home weekends and nights when she is avidly reading other people's words while reclining on our marital bed under a crinkling spread of manuscript pages that lie atop our designer duvet or between the sheets, which in due time she will shake out in order to reclaim the pages and stack them neatly on her bedside table before turning out the lights and possibly dreaming of when the pages will be transformed into a beautifully bound, critically acclaimed book.

In any event, on this weekend when we decided (she decided) to remain in New York, and while she was upstairs editing the chapters of a manuscript we had slept with on Friday night, I was downstairs watching the Yankee-Mets game (the Yankees took a quick 2-0 lead on Paul O'Neill's first-inning homer, following Bernie Williams's single). Between innings I was thinking ahead to my tennis match and reminding myself that I must toss the ball higher when serving and seize every opportunity to get to the net.

I had been introduced to tennis by my gym teacher during my junior year in high school, and even though our school did not then field a tennis team, I played the game as often as I could during lunchtime recess because I could play it better than the ungainly classmates whom I selected as opponents and who also served under me as staff members on the student newspaper. That I never achieved distinction while competing on a varsity level in a major sport (football, basketball, baseball, or track) did not upset me because our school's teams were mediocre in these sports. Besides which, as the players' chronicler and potential critic (in addition to working on the school paper I wrote about sports as well as classroom activities in my extracurricular role as scholastic correspondent for my hometown weekly and the Atlantic City daily), I was suddenly experiencing the dubious eminence of being a journalist, of having my callow character and identity boosted, if not enhanced, by my bylined articles and the stamp-size photo of myself that appeared above my school-page column in the town weekly, to say nothing of the many privileges that were now mine to select, such as to travel to out-of-town games on the team bus in a reserved seat behind the coach, or to catch a ride later in a chrome-embellished Buick coup driven by the athletic director's pretty wife.

As ineffectual as the players usually were, fumbling the football constantly, striking out habitually, and missing most of their foul shots, I never humiliated them in print. I invariably found ways to describe delicately each team defeat, each individual inadequacy. I seemed to possess in my writing a precocious flare for rhetoric and circumlocution long before I could accurately spell either word. My approach to journalism was strongly influenced throughout my high school years by a florid novelist named Frank Yerby, a Georgia-born black man who later settled in Spain and wrote prolifically about bejeweled and crinoline-skirted women of such erotic excess that, were it not for Yerby's illusory prose style, which somehow obfuscated what to me was breathtakingly obscene, his books would have been censored throughout the United States, and I would have been denied the opportunity to request each and every one of them sheepishly from the proprietress of our town library, and furthermore would not then have tried to emulate Yerby's palliative way with words in my attempts to cloak and cover up the misdeeds and deficiencies of our school's athletes in my newspaper articles.

While my evasive and roundabout reportage might be ascribed to my desire to maintain friendly relations with the athletes and encourage their continuing participation in interviews, I believe that practical matters had far less to do with it than did my own youthful identity with disappointment and the fact that, except for my skill in writing pieces that softened the harsh reality of the truth, I could do nothing exceptionally well. The grades I received from teachers in elementary as well as high school consistently placed me in the lower half of my class. Next to chemistry and math, English was my worst subject. In 1949, I was rejected by the two dozen colleges that I applied to in my native state of New Jersey and neighboring Pennsylvania and New York. That I was accepted into the freshman class at the University of Alabama was entirely the result of my father's appeals to a magnanimous Birmingham-born physician who practiced in our town and wore suits superbly designed and tailored by my father, and by this physician's own subsequent petitions on my behalf to his onetime classmate and everlasting friend then serving as Alabama's dean of admissions.

My main achievements during my four years on the Alabama campus were being appointed sports editor of the college weekly and the popularity I gained through my authorship of a column called "Sports Gay-zing," which, often blending humor with solicitousness and a veiled viewpoint, made the best of perhaps some of the worst displays of athleticism in the school's proud history. Even the Alabama football team, long accustomed to justifying its national reputation as a perennial top-ten powerhouse, suffered when I was a student through many days sadder than any since the Civil War. While gridiron glory would be restored after 1958 with the arrival of the now legendary coach Paul "Bear" Bryant, the football schedule during my time was more often than not the cause of a statewide weekend wake; and the coach of the team, a New Englander named Harold "Red" Drew, was routinely burned in effigy on Saturday nights in the center of the campus by raucous crowds of fraternity men and their girlfriends from sororities in which the pledges had spent the afternoon sewing together sackcloth body-size figures with bug eyes and fat rouge-smeared faces that were supposed to replicate the features of Red Drew.

Although Drew never complained about any of this to me or my staff, I began to feel very sorry for him, and in our sports section I always tried to put a positive spin on his downward-spiraling career. In one of my columns I emphasized the valor he had shown while serving his country as a naval officer in World War I, highlighting an occasion on which he had jumped two thousand feet from a blimp into the Gulf of Mexico. This leap in 1917, when Drew was an ensign, established him as the first parachute jumper in naval history, or so I wrote after getting the information from a yellowed newspaper clipping that was pasted in an old scrapbook lent to me by the coach's wife. I also illustrated what I wrote with a World War I–vintage photograph showing a lean and broad-shouldered Ensign Drew standing in front of a double-winged navy fighter plane at a base in the Panama Canal, wearing jodhpurs and knee-high boots and an officer's cap decorated with an insignia and bearing a peak that shaded his eyes from the sun without concealing an understated smile that I hoped my readers would see as the mark of a modest and fearless warrior—thinking, naïvely, that this would arouse their patriotism and extinguish a few of the nighttime torches that they raised in vilifying Coach Drew and also at times his venerable assistant, Henry "Hank" Crisp, who specialized in directing Alabama's porous front line of defense.

In yet another futile attempt on my part to divert the fans from such disastrous performances as were customarily presented throughout such seasons as 1951, for example, when the team lost six out of eleven games, I dramatized the tragedy partly with words lifted from Shakespeare:

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis Drew or Crisp who must suffer the

slings and arrows of outrageous blocking, or to take

arms against football writers, and by opposing end

them?

To win: to lose: to get wrecked, routed, o'erwhelmed

and consumed by prissy Villanova. . . .

Ah, to sleep, for in that sleep of death one dreams

of our opponents who plunged and fled with leather football

under arm, around, under, and over Bama walls. . . .

I left Red Drew to his own fate following my graduation in the spring of 1953. A year later I read that he had resigned in the wake of his team's 4-5-2 record, which might have been considered outstanding if compared with the accomplishments of his successor, J. B. "Ears" Whitworth, who in 1955 lost ten games without winning even one. During these two years I did not return to the campus to witness any of these engagements, being assigned for my military service to an armored unit in Kentucky much of the time, and then stationed with that unit in Germany for part of the time, until my discharge in the winter of 1955 enabled me to accept a reportorial job in the sports department of the New York Times.

Descriere

One of the most influential nonfiction writers of his generation pens a candid, humorous, deeply impassioned, and dazzling book about the nature of writing in one man's life, and of writing itself.