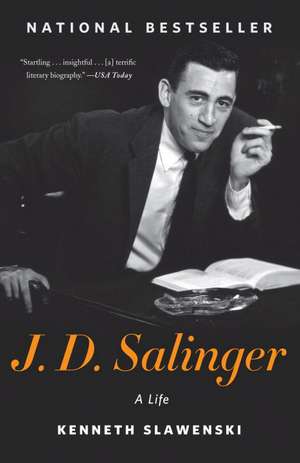

J. D. Salinger

Autor Kenneth Slawenskien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2011

One of the most popular and mysterious figures in American literary history, the author of the classic Catcher in the Rye, J. D. Salinger eluded fans and journalists for most of his life. Now he is the subject of this definitive biography, which is filled with new information and revelations garnered from countless interviews, letters, and public records. Kenneth Slawenski explores Salinger’s privileged youth, long obscured by misrepresentation and rumor, revealing the brilliant, sarcastic, vulnerable son of a disapproving father and doting mother. Here too are accounts of Salinger’s first broken heart—after Eugene O’Neill’s daughter, Oona, left him—and the devastating World War II service that haunted him forever. J. D. Salinger features all the dazzle of this author’s early writing successes, his dramatic encounters with luminaries from Ernest Hemingway to Elia Kazan, his office intrigues with famous New Yorker editors and writers, and the stunning triumph of The Catcher in the Rye, which would both make him world-famous and hasten his retreat into the hills of New Hampshire. J. D. Salinger is this unique author’s unforgettable story in full—one that no lover of literature can afford to miss.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 148.06 lei 22-36 zile | |

| Random House Trade – 31 dec 2011 | 148.06 lei 22-36 zile | |

| Hardback (1) | 140.05 lei 22-36 zile | +32.21 lei 5-11 zile |

| Pomona – 9 mar 2010 | 140.05 lei 22-36 zile | +32.21 lei 5-11 zile |

Preț: 148.06 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 222

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.33€ • 29.66$ • 23.44£

28.33€ • 29.66$ • 23.44£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812982596

ISBN-10: 0812982592

Pagini: 464

Ilustrații: 15 BLACK-&-WHITE PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 141 x 206 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812982592

Pagini: 464

Ilustrații: 15 BLACK-&-WHITE PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 141 x 206 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Recenzii

“Startling . . . insightful . . . [a] terrific literary biography.”—USA Today

“It is unlikely that any author will do a better job than Mr. Slawenski capturing the glory of Salinger’s life.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Slawenski fills in a great deal and connects the dots assiduously; it’s unlikely that any future writer will uncover much more about Salinger than he has done.”—Boston Sunday Globe

“Offers perhaps the best chance we have to get behind the myth and find the man.”—Detroit Free Press

“[Slawenski has] greatly fleshed out and pinned down an elusive story with precision and grace.”—Chicago Sun-Times

“Earnest, sympathetic and perceptive . . . [Slawenski] does an evocative job of tracing the evolution of Salinger’s work and thinking.”—The New York Times

“It is unlikely that any author will do a better job than Mr. Slawenski capturing the glory of Salinger’s life.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Slawenski fills in a great deal and connects the dots assiduously; it’s unlikely that any future writer will uncover much more about Salinger than he has done.”—Boston Sunday Globe

“Offers perhaps the best chance we have to get behind the myth and find the man.”—Detroit Free Press

“[Slawenski has] greatly fleshed out and pinned down an elusive story with precision and grace.”—Chicago Sun-Times

“Earnest, sympathetic and perceptive . . . [Slawenski] does an evocative job of tracing the evolution of Salinger’s work and thinking.”—The New York Times

Notă biografică

Kenneth Slawenski is the creator of DeadCaulfields.com, a website founded in 2004 and recommended by The New York Times. He has been working on this biography for eight years. Slawenski was born in New Jersey, and has lived there all his life.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1. Sonny

The Great War had changed everything. As 1919 dawned, people awoke to a fresh new world, one filled with promise but uncertainty. Old ways of life, beliefs and assumptions unchallenged for decades, were now called into question or swept away. The guns had fallen silent only weeks before. The Old World now lay in ruins. In its place stood a new nation poised to assume the mantle of leadership. No place in that land was more anxious or more ready than the city of New York.

It was the first day of the first year of peace when Miriam Jillich Salinger gave birth to a son. His sister, Doris, had been born six years before. In the years since Doris’s birth, Miriam had suffered a series of miscarriages.

This child too was almost lost. So it was with a mixture of joy and relief that Miriam and Solomon Salinger welcomed their son into the world. They named him Jerome David, but from the very first day, they called him Sonny.

Sonny was born into a middle-class Jewish family that was both unconventional and ambitious. The Salinger line reached back to the ?village of Sudargas, a tiny Jewish settlement (shtetl) situated on the Polish-Lithuanian border of the Russian Empire, a village where, rec?ords show, the family had lived at least since 1831. But the Salingers were not given to tradition or nostalgia. By the time Sonny was born, their link to that world had nearly evaporated. Sonny’s father was robust and motivated, determined to go his own way in life. Typical of the sons of immigrants, he had resolved to free himself of any connection with the world of his parents’ birth, a place he considered backward. Unknown to Solomon at the time, his rebellion was actually a family tradition. The Salingers had gone their own way for generations, seldom looking back and growing increasingly prosperous with each step. As Sonny would one day reflect, his ancestors had an amazing penchant “for diving from immense heights into small containers of water”—and hitting their mark every time.1

Hyman Joseph Salinger, Sonny’s great-grandfather, had moved from Sudargas to the more prosperous town of Taurage in order to marry into a prominent family. Through his writings, J. D. Salinger later immortalized his great-grandfather as the clown Zozo, honor- ing him as the family patriarch and confiding that he felt his great-?grandfather’s spirit always watched over him. Hyman Joseph remained in Russia all his life and died nine years before the birth of his great-grandson. Salinger knew of him only through a photograph, an image that offered a glimpse into another world. It depicted an elderly peasant brimming with nobility, erect in his long black gown and flowing white beard, and sporting a tremendous nose—a feature that Salinger confessed made him shudder with apprehension.2

Sonny’s grandfather Simon F. Salinger was also ambitious. In 1881, a year of famine (though not in Taurage itself), he left home and family and immigrated to the United States. Soon after arriving in America, Simon married Fannie Copland, also a Lithuanian immigrant, at Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The couple then moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where they found an apartment in one of the city’s many immigrant neighborhoods and where, on March 16, 1887, Fannie gave birth to Sonny’s father, Solomon, the second of five surviving children.3

By 1893, the Salingers were living in Louisville, Kentucky, where Simon attended medical school. His religious training in Russia served him well, enabling him to practice as a rabbi in order to finance his education.4 Upon obtaining his medical degree, Simon left the pulpit and, after a brief return to Pennsylvania, moved the family to its final destination in the center of Chicago, where he set up a general practice not far from Cook County Hospital.5 Sonny knew his grandfather well, as do readers of The Catcher in the Rye. Dr. Salinger often traveled to New York to visit his son and was the basis of Holden Caulfield’s grandfather, the endearing man who would embarrass Holden by read?ing all the street signs aloud while riding on the bus. Simon Salinger died in 1960, just short of his hundredth birthday.

...

In the opening lines of The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield refuses to share his parents’ past with the reader, deriding any recount of “how they were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap.” “My parents,” he explains, “would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them.” This apparent elusiveness on the part of Holden’s parents was imported directly from the attitudes of Salinger’s own mother and father. Sol and Miriam rarely spoke of past events, especially to their children, and their attitude created an air of secrecy that permeated the Salinger household and caused Doris and Sonny to grow into intensely private people.

The Salingers’ insistence upon privacy also led to rumors. Over the years, Miriam and Sol’s story has been repeatedly embellished. This began in 1963, when the literary critic Warren French repeated a claim in a Life magazine article that Miriam had been Scotch-Irish. In time, the term “Scotch-Irish” transformed itself into the assertion that Salinger’s mother had actually been born in County Cork, Ireland. This led in turn to what is perhaps the most commonly repeated story told about Salinger’s mother and father: that Miriam’s parents, supposedly Irish Catholic, were so adamantly opposed to her marriage to Sol, because he was Jewish, that they gave the couple little choice but to elope. And, upon learning of their daughter’s defiance, they never spoke a word to her again.

None of this has any basis in fact, yet by the time of her death in 2001, even Salinger’s sister, Doris, had been persuaded that her mother had been born in Ireland and that she and Sonny had been purposely denied a relationship with their grandparents.

The circumstances surrounding Miriam’s family and her marriage to Sol were quite painful enough without embroidery through rumor. However, Salinger’s parents exacerbated that pain by attempting to conceal their past from their children. In doing so, they not only invited fictitious versions of their history but confused their children too. By attempting to restrain Doris’s and Sonny’s natural curiosity, Miriam and Sol actually gave credence to a fabricated past that remained with them all their lives.

Sonny’s mother was born Marie Jillich on May 11, 1891, in the small midwestern town of Atlantic, Iowa.6 Her parents, Nellie and George Lester Jillich, Jr., were twenty and twenty-four, respectively, at the time of her birth, and records show that she was the second of six surviving children.7 Marie’s grandparents George Lester Jillich, Sr., and Mary Jane Bennett had been the first Jillichs to settle in Iowa. The grandson of German immigrants, George, Sr., had moved from Mas?sachusetts to Ohio, where he met and married his wife. He served briefly with the 192nd Ohio Regiment during the Civil War, and after he returned home in 1865, Mary Jane gave birth to Marie’s father. George, Sr., eventually established himself as a successful grain merchant and by 1891 was in firm position as head of the Jillich clan, with his sons George, Jr., and Frank following him into the trade.

Although Marie later maintained that her mother, Nellie McMahon, had been born in Kansas City in 1871, the daughter of Irish immigrants, four sets of federal census records (1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930) suggest that she is more likely to have come from Iowa. Family tradition has it that Marie met Solomon early in 1910 at a county fair near the Jillich family farm (an unlikely location since no such farm existed). The manager of a Chicago movie theater, Solomon, who was called “Sollie” by his family and “Sol” by his friends, was six feet tall with a whiff of big-city sophistication. Just seventeen, Marie was an arresting beauty, with fair skin and long red hair that contrasted with Sol’s olive complexion. Their romance was immediate and intense, and Sol was determined to marry Marie from the start.

A rapid series of events, some of them heartbreaking, would occur that year, culminating in Marie’s marriage to Sol in the spring of 1910. While the Salingers had steadily improved their position since Simon’s arrival, the Jillichs had suddenly encountered difficulties. Marie’s father had died the previous year.8 Unable to keep the family afloat, her mother had taken the youngest of the children and relocated to Michigan, where she later remarried. Marie did not move with her mother, because of her age and her relationship with Sol. Her swift romance and marriage to Solomon therefore proved to be providential, especially when, by the time of Sonny’s birth in 1919, her mother, Nellie, had also died.9 The loss of both parents was possibly enough to make Marie reluctant to discuss them even with her own children. Rather than cling to the past, she devoted herself completely to a new life with her new husband. Left with only the Salingers now as family, she sought their acceptance by embracing Judaism and changing her name to Miriam, after the sister of Moses.

Simon and Fannie thought that Marie, with her milky-fair skin and auburn hair, looked like “a little Irisher.”10 In a city with thousands of eligible Jewish girls, they never dreamed that Sollie would bring home a red-haired Gentile from Iowa, but they accepted Miriam as their new daughter-in-law, and she soon moved into their Chicago home.

Miriam joined Sol working at the movie theater, where she sold tickets and concessions. Despite their efforts, the theater was unsuccessful and was forced to close, sending the new bridegroom in search of employment. He soon found a position working for J. S. Hoffman & Company, an importer of European cheeses and meats that went by the brand name Hofco. After the disappointment with the theater, Sol swore never to fail at business again and applied himself to his new company duties with devotion. This dedication paid off, and after Doris’s birth in December 1912, he was promoted to general manager of Hoffman’s New York division, becoming, as he coolly declared, “the manager of a cheese factory.”

Sol’s new position required the Salingers to move to New York City, where they settled into a comfortable apartment at 500 West 113th Street, close to Columbia University and the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. Although Sol was now in the business of vending a series of hams—distinctly the most unkosher of foods—along with his cheeses, he had managed to continue the Salinger custom of advancing beyond the previous generation, an accomplishment of which he was extraordinarily proud. But business became his life, and by the time of his thirtieth birthday in 1917, his hair had gone completely “iron grey.”12

...

Until he was thirteen, Sonny attended public school on the Upper West Side. This is a class photo of Salinger and his schoolmates on the steps of P.S. 166, circa 1929.

The 1920s were years of unparalleled prosperity, and no place shone brighter than New York City. It was the economic, cultural, and intellectual capital of the Americas, perhaps even of the world. Its values were beamed across the continent through radio and absorbed by millions through publications. Its streets held sway over the economic vitality of nations, and its advertising and markets determined the desires and tastes of a generation. In this opportune place and time, the Salin?gers thrived.

Between the years of Sonny’s birth in 1919 through to 1928, Sol and Miriam moved the family three times, always to a more affluent Manhattan neighborhood. When Sonny was born, they were living at 3681 Broadway, in an apartment located in North Harlem. Before year’s end, they had moved back to their original New York neighborhood, into a residence at 511 West 113th Street. A more ambitious move came in 1928, when the family rented an apartment just a few blocks from Central Park at 215 West 82nd Street. This home came complete with servants’ quarters, and Sol and Miriam quickly hired a live-in maid, an Englishwoman named Jennie Burnett. Sonny grew up in a world of increasing comfort, insulated by his parents’ indulgence and their growing social status.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Great War had changed everything. As 1919 dawned, people awoke to a fresh new world, one filled with promise but uncertainty. Old ways of life, beliefs and assumptions unchallenged for decades, were now called into question or swept away. The guns had fallen silent only weeks before. The Old World now lay in ruins. In its place stood a new nation poised to assume the mantle of leadership. No place in that land was more anxious or more ready than the city of New York.

It was the first day of the first year of peace when Miriam Jillich Salinger gave birth to a son. His sister, Doris, had been born six years before. In the years since Doris’s birth, Miriam had suffered a series of miscarriages.

This child too was almost lost. So it was with a mixture of joy and relief that Miriam and Solomon Salinger welcomed their son into the world. They named him Jerome David, but from the very first day, they called him Sonny.

Sonny was born into a middle-class Jewish family that was both unconventional and ambitious. The Salinger line reached back to the ?village of Sudargas, a tiny Jewish settlement (shtetl) situated on the Polish-Lithuanian border of the Russian Empire, a village where, rec?ords show, the family had lived at least since 1831. But the Salingers were not given to tradition or nostalgia. By the time Sonny was born, their link to that world had nearly evaporated. Sonny’s father was robust and motivated, determined to go his own way in life. Typical of the sons of immigrants, he had resolved to free himself of any connection with the world of his parents’ birth, a place he considered backward. Unknown to Solomon at the time, his rebellion was actually a family tradition. The Salingers had gone their own way for generations, seldom looking back and growing increasingly prosperous with each step. As Sonny would one day reflect, his ancestors had an amazing penchant “for diving from immense heights into small containers of water”—and hitting their mark every time.1

Hyman Joseph Salinger, Sonny’s great-grandfather, had moved from Sudargas to the more prosperous town of Taurage in order to marry into a prominent family. Through his writings, J. D. Salinger later immortalized his great-grandfather as the clown Zozo, honor- ing him as the family patriarch and confiding that he felt his great-?grandfather’s spirit always watched over him. Hyman Joseph remained in Russia all his life and died nine years before the birth of his great-grandson. Salinger knew of him only through a photograph, an image that offered a glimpse into another world. It depicted an elderly peasant brimming with nobility, erect in his long black gown and flowing white beard, and sporting a tremendous nose—a feature that Salinger confessed made him shudder with apprehension.2

Sonny’s grandfather Simon F. Salinger was also ambitious. In 1881, a year of famine (though not in Taurage itself), he left home and family and immigrated to the United States. Soon after arriving in America, Simon married Fannie Copland, also a Lithuanian immigrant, at Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The couple then moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where they found an apartment in one of the city’s many immigrant neighborhoods and where, on March 16, 1887, Fannie gave birth to Sonny’s father, Solomon, the second of five surviving children.3

By 1893, the Salingers were living in Louisville, Kentucky, where Simon attended medical school. His religious training in Russia served him well, enabling him to practice as a rabbi in order to finance his education.4 Upon obtaining his medical degree, Simon left the pulpit and, after a brief return to Pennsylvania, moved the family to its final destination in the center of Chicago, where he set up a general practice not far from Cook County Hospital.5 Sonny knew his grandfather well, as do readers of The Catcher in the Rye. Dr. Salinger often traveled to New York to visit his son and was the basis of Holden Caulfield’s grandfather, the endearing man who would embarrass Holden by read?ing all the street signs aloud while riding on the bus. Simon Salinger died in 1960, just short of his hundredth birthday.

...

In the opening lines of The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield refuses to share his parents’ past with the reader, deriding any recount of “how they were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap.” “My parents,” he explains, “would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them.” This apparent elusiveness on the part of Holden’s parents was imported directly from the attitudes of Salinger’s own mother and father. Sol and Miriam rarely spoke of past events, especially to their children, and their attitude created an air of secrecy that permeated the Salinger household and caused Doris and Sonny to grow into intensely private people.

The Salingers’ insistence upon privacy also led to rumors. Over the years, Miriam and Sol’s story has been repeatedly embellished. This began in 1963, when the literary critic Warren French repeated a claim in a Life magazine article that Miriam had been Scotch-Irish. In time, the term “Scotch-Irish” transformed itself into the assertion that Salinger’s mother had actually been born in County Cork, Ireland. This led in turn to what is perhaps the most commonly repeated story told about Salinger’s mother and father: that Miriam’s parents, supposedly Irish Catholic, were so adamantly opposed to her marriage to Sol, because he was Jewish, that they gave the couple little choice but to elope. And, upon learning of their daughter’s defiance, they never spoke a word to her again.

None of this has any basis in fact, yet by the time of her death in 2001, even Salinger’s sister, Doris, had been persuaded that her mother had been born in Ireland and that she and Sonny had been purposely denied a relationship with their grandparents.

The circumstances surrounding Miriam’s family and her marriage to Sol were quite painful enough without embroidery through rumor. However, Salinger’s parents exacerbated that pain by attempting to conceal their past from their children. In doing so, they not only invited fictitious versions of their history but confused their children too. By attempting to restrain Doris’s and Sonny’s natural curiosity, Miriam and Sol actually gave credence to a fabricated past that remained with them all their lives.

Sonny’s mother was born Marie Jillich on May 11, 1891, in the small midwestern town of Atlantic, Iowa.6 Her parents, Nellie and George Lester Jillich, Jr., were twenty and twenty-four, respectively, at the time of her birth, and records show that she was the second of six surviving children.7 Marie’s grandparents George Lester Jillich, Sr., and Mary Jane Bennett had been the first Jillichs to settle in Iowa. The grandson of German immigrants, George, Sr., had moved from Mas?sachusetts to Ohio, where he met and married his wife. He served briefly with the 192nd Ohio Regiment during the Civil War, and after he returned home in 1865, Mary Jane gave birth to Marie’s father. George, Sr., eventually established himself as a successful grain merchant and by 1891 was in firm position as head of the Jillich clan, with his sons George, Jr., and Frank following him into the trade.

Although Marie later maintained that her mother, Nellie McMahon, had been born in Kansas City in 1871, the daughter of Irish immigrants, four sets of federal census records (1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930) suggest that she is more likely to have come from Iowa. Family tradition has it that Marie met Solomon early in 1910 at a county fair near the Jillich family farm (an unlikely location since no such farm existed). The manager of a Chicago movie theater, Solomon, who was called “Sollie” by his family and “Sol” by his friends, was six feet tall with a whiff of big-city sophistication. Just seventeen, Marie was an arresting beauty, with fair skin and long red hair that contrasted with Sol’s olive complexion. Their romance was immediate and intense, and Sol was determined to marry Marie from the start.

A rapid series of events, some of them heartbreaking, would occur that year, culminating in Marie’s marriage to Sol in the spring of 1910. While the Salingers had steadily improved their position since Simon’s arrival, the Jillichs had suddenly encountered difficulties. Marie’s father had died the previous year.8 Unable to keep the family afloat, her mother had taken the youngest of the children and relocated to Michigan, where she later remarried. Marie did not move with her mother, because of her age and her relationship with Sol. Her swift romance and marriage to Solomon therefore proved to be providential, especially when, by the time of Sonny’s birth in 1919, her mother, Nellie, had also died.9 The loss of both parents was possibly enough to make Marie reluctant to discuss them even with her own children. Rather than cling to the past, she devoted herself completely to a new life with her new husband. Left with only the Salingers now as family, she sought their acceptance by embracing Judaism and changing her name to Miriam, after the sister of Moses.

Simon and Fannie thought that Marie, with her milky-fair skin and auburn hair, looked like “a little Irisher.”10 In a city with thousands of eligible Jewish girls, they never dreamed that Sollie would bring home a red-haired Gentile from Iowa, but they accepted Miriam as their new daughter-in-law, and she soon moved into their Chicago home.

Miriam joined Sol working at the movie theater, where she sold tickets and concessions. Despite their efforts, the theater was unsuccessful and was forced to close, sending the new bridegroom in search of employment. He soon found a position working for J. S. Hoffman & Company, an importer of European cheeses and meats that went by the brand name Hofco. After the disappointment with the theater, Sol swore never to fail at business again and applied himself to his new company duties with devotion. This dedication paid off, and after Doris’s birth in December 1912, he was promoted to general manager of Hoffman’s New York division, becoming, as he coolly declared, “the manager of a cheese factory.”

Sol’s new position required the Salingers to move to New York City, where they settled into a comfortable apartment at 500 West 113th Street, close to Columbia University and the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. Although Sol was now in the business of vending a series of hams—distinctly the most unkosher of foods—along with his cheeses, he had managed to continue the Salinger custom of advancing beyond the previous generation, an accomplishment of which he was extraordinarily proud. But business became his life, and by the time of his thirtieth birthday in 1917, his hair had gone completely “iron grey.”12

...

Until he was thirteen, Sonny attended public school on the Upper West Side. This is a class photo of Salinger and his schoolmates on the steps of P.S. 166, circa 1929.

The 1920s were years of unparalleled prosperity, and no place shone brighter than New York City. It was the economic, cultural, and intellectual capital of the Americas, perhaps even of the world. Its values were beamed across the continent through radio and absorbed by millions through publications. Its streets held sway over the economic vitality of nations, and its advertising and markets determined the desires and tastes of a generation. In this opportune place and time, the Salin?gers thrived.

Between the years of Sonny’s birth in 1919 through to 1928, Sol and Miriam moved the family three times, always to a more affluent Manhattan neighborhood. When Sonny was born, they were living at 3681 Broadway, in an apartment located in North Harlem. Before year’s end, they had moved back to their original New York neighborhood, into a residence at 511 West 113th Street. A more ambitious move came in 1928, when the family rented an apartment just a few blocks from Central Park at 215 West 82nd Street. This home came complete with servants’ quarters, and Sol and Miriam quickly hired a live-in maid, an Englishwoman named Jennie Burnett. Sonny grew up in a world of increasing comfort, insulated by his parents’ indulgence and their growing social status.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

In this national bestseller, Slawenski examines the life of one of the most popular and mysterious figures in American literary history, the author of the classic "Catcher in the Rye," J.D. Salinger.