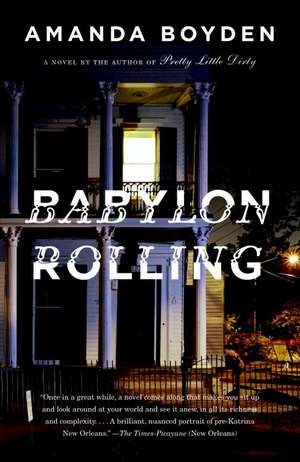

Babylon Rolling: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America: Vintage Contemporaries

Autor Amanda Boydenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

Din seria Vintage Contemporaries

-

Preț: 109.95 lei

Preț: 109.95 lei -

Preț: 101.80 lei

Preț: 101.80 lei -

Preț: 96.52 lei

Preț: 96.52 lei -

Preț: 107.46 lei

Preț: 107.46 lei -

Preț: 91.77 lei

Preț: 91.77 lei -

Preț: 101.88 lei

Preț: 101.88 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 119.87 lei

Preț: 119.87 lei -

Preț: 87.84 lei

Preț: 87.84 lei -

Preț: 97.34 lei

Preț: 97.34 lei -

Preț: 111.92 lei

Preț: 111.92 lei -

Preț: 117.87 lei

Preț: 117.87 lei -

Preț: 95.92 lei

Preț: 95.92 lei -

Preț: 113.56 lei

Preț: 113.56 lei -

Preț: 132.88 lei

Preț: 132.88 lei -

Preț: 108.09 lei

Preț: 108.09 lei -

Preț: 115.42 lei

Preț: 115.42 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 99.60 lei

Preț: 99.60 lei -

Preț: 105.82 lei

Preț: 105.82 lei -

Preț: 99.30 lei

Preț: 99.30 lei -

Preț: 129.78 lei

Preț: 129.78 lei -

Preț: 103.74 lei

Preț: 103.74 lei -

Preț: 100.98 lei

Preț: 100.98 lei -

Preț: 100.76 lei

Preț: 100.76 lei -

Preț: 89.09 lei

Preț: 89.09 lei -

Preț: 115.94 lei

Preț: 115.94 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 125.13 lei

Preț: 125.13 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 100.35 lei

Preț: 100.35 lei -

Preț: 139.63 lei

Preț: 139.63 lei -

Preț: 93.85 lei

Preț: 93.85 lei -

Preț: 106.45 lei

Preț: 106.45 lei -

Preț: 96.11 lei

Preț: 96.11 lei -

Preț: 107.92 lei

Preț: 107.92 lei -

Preț: 77.02 lei

Preț: 77.02 lei -

Preț: 125.21 lei

Preț: 125.21 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 112.11 lei

Preț: 112.11 lei -

Preț: 83.94 lei

Preț: 83.94 lei -

Preț: 101.58 lei

Preț: 101.58 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 97.15 lei

Preț: 97.15 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 100.57 lei -

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 82.48 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 124

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.78€ • 16.31$ • 13.14£

15.78€ • 16.31$ • 13.14£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307388247

ISBN-10: 0307388247

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 136 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

ISBN-10: 0307388247

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 136 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

Notă biografică

Amanda Boyden was born in Minnesota and raised in Chicago and St. Louis. Formerly a circus trapeze artist and contortionist, she earned her MFA from the University of New Orleans, where she now teaches writing. Her first novel, Pretty Little Dirty was published in 2006.

Extras

Fearius stare from the car at Stumps Grocery and Liquor. Painted on the siding: Package meat Fried rice Cold drinks. He might could drink a strawberry cold drink. Orange. Fearius like cold drinks better than malt liquor when they smokin the hydroponic, but Alphonse be inside Stumps for Colt 40s, and Fearius, his bankroll thin as a spliff now. Thin as quarters and a dime thin. Juvey dont pay, dont he know.

But Fearius, he be patient. He learnt it. He waited to make fifteen full years of age inside juvey, waited four months sitting in there. Finally turned legal for driving on a learner permit when he caged up in Baby Angola with no wheels nowhere. Now he borrowing a license till he take the test. Why he hafta take a test to drive when he been driving since he made twelve, Fearius dont know. Maybe he just go buy a license. He be working soon, back tight with everybody, two weeks, three, fatten up the bitch bankroll.

Fearius flick the cardboard tree smell like piña colada on the rear- view, rag the sweat off his shaved head. He open the glovebox and touch Alphonses Glock. Pretty thing, hot as they get. Stinkin like firecrackers.

Alphonse walk out Stumps and pass Fearius a 40 in brown paper, wet on the bottom, sweatin. Everything sweatin. Fearius dick sweatin in his drawers.

“You want it?” Alphonse ask about the gun. Or maybe the beer.

“I earn it,” Fearius say about the Glock and the 40 both.

Alphonse nod, get in, take the Glock and shove it in his pants.

Two hours still before Shandra off work. Shandra gots a friend, she say. Fearius need, need, need a friend. He just gone take a friend soon, he toll Alphonse. Alphonse said, “Be patient.” Fearius remember he know patient. And Alphonse gots the Glock. Patient be way easier with a gun.

Autumn is running around in a circle at the end of its tether, Ariel May decides, as far away as it can get from the stake of New Orleans. She misses fall with a pang, squints against the thick afternoon sun, licks salty sweat from her upper lip. The streetcar stinks of too many bodies and is full of noise, and the junior high school kids in their uniforms and blue braids and attitudes with music leaking out of the little speakers crammed into their ears irritate Ariel enough so that she uncrosses her legs and takes up more room on the wooden seat, presses her hot thigh beneath her wrinkled linen skirt against the loud girl next to her. The girl can’t be more than twelve, Ariel surmises, but she has C-cup tits at least, maybe Ds. How does a body so young grow those things? Maybe the girl is older. Maybe she’s dumb and has failed a couple of grades.

The girl doesn’t notice Ariel’s leg at all though. Instead, she busily rubs some kind of pale salve the consistency of mucus onto the propped-up elbows of the girl squatting on the seat in front of her and blathers on about what another girl did. She’ll bust her fuckin skinny-ass face if she thinks about fuckin doin it again. A cursive tattoo shows on the second girl’s upper arm through the short sleeve of her thin white uniform shirt. Ariel wants to swat the tub of goo out the open window. She’s tired. Hot, hot. Here, inside this streetcar, perpetual summer drapes itself around Ariel’s neck like a stole. Like a giant piece of raw bacon stole.

The streetcar squeals to another stop. Two waiters in their black and whites squeeze on. The junior high kids jammed up front fan their noses and talk about the waiters’ pizza funk and pepperoni faces. When the streetcar takes off again, the little breeze that snakes its way past the salving girls is a drooly lick. A breeze almost worse than none. Ariel sighs and remembers woodsmoke, brown leaves dancing across a sidewalk. The people who have lived here their entire lives can’t have any idea what they’re missing.

She wonders what Ed will make for dinner. She wonders about her commitment to public transportation in a city like this.

Ed hollers hello from the kitchen. Miles and Ella bicker above the somber narration of Animal Planet surgery: “Lucky’s femur is broken in five places.” Ariel saves her breath. The instant she’d confront Ed about their children watching surgical gore is the instant he’d take the remote, change the channel, and say, “What gore? There. Look. PBS.” And smile. She’s given up on training him to greet her at the door with a martini.

“Changing!” Ariel yells, ascending the stairs. The house groans out its age with each footfall.

In September, cold water only runs cool. Ariel drops her head in the shower. She waits, knows that the water temperature won’t change, feels nostalgic, considers where, exactly, the best place is to apply a cold pack to drop body temperature. Wrist. Throat. Sliceable places. Once, in Jamaica, a man put shell-shaped ice chips in her vagina in some form of misdirected foreplay. The ice melted. Even then, young as she was, the island and the guy alike felt fake to her. Practiced. She tries to remember the guy’s name, knows she can’t, not even to save her life.

The soap rests in a soupy muck in the holder. Ish. If Ed is going to tend house, then that’s what he should do, but he just doesn’t see things. Giant snot soap. How do you miss it?

She should be fair. Ed cooks. Ed listens to NPR.

What’s His Name, the ice chip man, had a washboard stomach. Ariel didn’t come. She knew she wouldn’t the instant he stood at the end of the bed and caressed his own waxed chest in some staged, amorous gesture. She has no recollection of whether his was a name that suited him or not.

Names hold too much power, she thinks, or none at all. Everyone should have a chance to name themselves. Just today “Miss Sugar Enspice” checked into the hotel. Ariel recognized the woman with crispy yellow extensions from her music video, the one where her plump ass cheeks hang out the bottom of a pair of kiwi-colored shorts.

Jesus, some of the pseudonyms that the celebrity guests use. Axel Savage. Rod Doe. Ha! Everybody behind the front desk busted guts. Rod Doe. Nameless Cock. The pubescent musician had no clue, it seemed, as he gave her, the general manager, very specific instructions on who could and who could not know his room number, what calls could be put through. He took off his dark sunglasses, stared directly into Ariel’s eyes the way some men’s magazine must have told him to do, and said she could use his room number. She felt at once mildly flattered and sick to her stomach. His dyed black hair stood in carefully spaced spikes all over his puny head. Ariel nodded politely. She bet he had acne on his back.

The idiotic name of the hotel itself can’t be beat: La Belle Nouvelle, a Barcelona-modern hotel through and through smushed into the French Quarter at the edge of the Central Business District. They don’t even have enough curb footage on the street to get zoned for valet parking. The bulk of the property rises orange and lime green, a contemporary cyst, in the center of the block between a department store and three empty buildings being forever renovated, the continual drilling and pneumatic hammering deafening to everyone but touring bands and the feckless groupies for whom the hotel has become a favorite. Ooh, and she can’t forget the proms. Or the frat and sorority formals. Somehow, Ariel is supposed to change the clientele. A year ago April, when the new owners called Minneapolis and made the offer she couldn’t refuse, she thought the name La Belle Nouvelle was likely reflective of some sort of New Orleans charm she hadn’t yet experienced. Ah. Well.

Their own family’s names always hover, too. Fruit fly names that won’t leave. Ariel kept her surname when they married, and they gave it to their kids. Ed, fortunately, has always believed the decision to be best. But then Edgar Allan Flank is a toughie of a moniker. Ariel and Ed couldn’t break completely from family tradition though. They chose two classics for their children: Miles Davis May and Ella Fitzgerald May. Ella will answer to the nickname Fitzy when she has no choice. Drying off, walking naked into their warm bedroom, Ariel again hopes they haven’t burdened their children with expectations of greatness.

Fearius sit, full-up tired of patient. His ass sore, done molded to the car seat by now. Shandra and Alphonse fighting and fighting on her stoop. “I say I finish for seven!” she scream at him.

Alphonse dont care, mixed everything up. Now Fearius not gettin no Shandra friends pussy.

Alphonse got the Glock in his pants still, in there for hours. Fearius feel like his dick a gun, feel like shooting big old lumpy Shandra with her witchy claws that cost more than Dom Pérignon. Except Alphonse got the Glock, so Fearius not getting no fat Shandra neither.

Fearius decide to quit Alphonses company till tomorrow. Tonight Fearius gone make a girlfriend, no matter what, make sure no Glocks nearby.

It a hot night, time he make hisself a girlfriend in the Channel by Annunciation. Lots of them over there when it hot, clucking, all together on corners like hens. Bunch a chicken heads.

Kissin between houses can turn into a lay down in no time.

“The goopas are purple,” Ella says, kicking the table leg. Ariel’s daughter peels cheese from the top of her lasagna with her fingers. Her chipped nail polish has disappeared.

“Guptas,” Miles enunciates.

“What?” Ariel understands her kids less each day. She knows she should be frightened by this fact. “What are guptas?”

Miles, Ella, and Ed giggle. “Who,” Ed says. “They’re a who.”

“What?”

“Mah-um!”

“Ed?”

“We say ‘people of color,’ ” Ed instructs Ella, and Miles rolls his eyes. So does Ariel.

“Ed?”

“Uh huh.” Ella nods. “Dark dark purple.”

“Nah ah.”

The junior high people of color on the streetcar today gyrated in the aisle. Ariel tries to remember dancing at twelve. A table for twelve. A party of twelve. Here in this city she’s learned everybody says, about a time, I’ll be there for twelve. I have to be there for six. We need a reservation for nine for seven. In such instances, Ariel has yet to figure out which way they want the reservation. A bellhop told her it comes from the French, which automatically means it doesn’t make any sense to Ariel. Sadly, no matter what Ariel tries, La Belle Nouvelle’s high-end dinner-bar retains a reputation for serving underage drinkers.

The dancing kids filled the aisle. They seemed to want to rile people of non-color on the streetcar. Why did she have to be a non-color? She has color. “Ed?”

“Our new neighbors,” he answers.

“They’re Indian,” Miles says knowingly.

Ed lays his hand on the table in front of Miles’ plate. “We say East Indian,” Ed corrects. This from the man who didn’t notice his daughter chewing on the end of the grape magic marker till the ink had covered her entire front in a purple indelible apron. Now Ella’s favorite color seems to be a shade of Gupta.

“Where?” Ariel asks, meaning which house. Two houses on their street have sold recently, the big one immediately to their right and a little one across the street next to the ratty community garden.

“Next door!” Miles yells.

“Next door!” Ella echoes and kicks the table leg again. “Next door!”

Ariel looks to Ed to see what he thinks. “Real new neighbors, then,” she says. Ed, the local stay-at-home dad, keeps a close watch on the neighborhood. He recognizes everybody. He knows the names of the teenagers who live on the block. He waves hello to some of the afternoon regulars who frequent the neighborhood bar, Tokyo Rose. Sitting diagonally across the street from their house, the little ugly thing looks like a residential shack decked out in Christmas decorations year-round. She could kill the realtor for not pointing it out to her as an up-and-running bar when she flew down to check out properties, but then again, kudos to Numbnuts for fooling her. She didn’t think to ask about it, and he didn’t offer. Kudos to New Orleans too for burying its bars so well that outsiders don’t even recognize them sitting square in the middle of a neighborhood block.

From the Hardcover edition.

But Fearius, he be patient. He learnt it. He waited to make fifteen full years of age inside juvey, waited four months sitting in there. Finally turned legal for driving on a learner permit when he caged up in Baby Angola with no wheels nowhere. Now he borrowing a license till he take the test. Why he hafta take a test to drive when he been driving since he made twelve, Fearius dont know. Maybe he just go buy a license. He be working soon, back tight with everybody, two weeks, three, fatten up the bitch bankroll.

Fearius flick the cardboard tree smell like piña colada on the rear- view, rag the sweat off his shaved head. He open the glovebox and touch Alphonses Glock. Pretty thing, hot as they get. Stinkin like firecrackers.

Alphonse walk out Stumps and pass Fearius a 40 in brown paper, wet on the bottom, sweatin. Everything sweatin. Fearius dick sweatin in his drawers.

“You want it?” Alphonse ask about the gun. Or maybe the beer.

“I earn it,” Fearius say about the Glock and the 40 both.

Alphonse nod, get in, take the Glock and shove it in his pants.

Two hours still before Shandra off work. Shandra gots a friend, she say. Fearius need, need, need a friend. He just gone take a friend soon, he toll Alphonse. Alphonse said, “Be patient.” Fearius remember he know patient. And Alphonse gots the Glock. Patient be way easier with a gun.

Autumn is running around in a circle at the end of its tether, Ariel May decides, as far away as it can get from the stake of New Orleans. She misses fall with a pang, squints against the thick afternoon sun, licks salty sweat from her upper lip. The streetcar stinks of too many bodies and is full of noise, and the junior high school kids in their uniforms and blue braids and attitudes with music leaking out of the little speakers crammed into their ears irritate Ariel enough so that she uncrosses her legs and takes up more room on the wooden seat, presses her hot thigh beneath her wrinkled linen skirt against the loud girl next to her. The girl can’t be more than twelve, Ariel surmises, but she has C-cup tits at least, maybe Ds. How does a body so young grow those things? Maybe the girl is older. Maybe she’s dumb and has failed a couple of grades.

The girl doesn’t notice Ariel’s leg at all though. Instead, she busily rubs some kind of pale salve the consistency of mucus onto the propped-up elbows of the girl squatting on the seat in front of her and blathers on about what another girl did. She’ll bust her fuckin skinny-ass face if she thinks about fuckin doin it again. A cursive tattoo shows on the second girl’s upper arm through the short sleeve of her thin white uniform shirt. Ariel wants to swat the tub of goo out the open window. She’s tired. Hot, hot. Here, inside this streetcar, perpetual summer drapes itself around Ariel’s neck like a stole. Like a giant piece of raw bacon stole.

The streetcar squeals to another stop. Two waiters in their black and whites squeeze on. The junior high kids jammed up front fan their noses and talk about the waiters’ pizza funk and pepperoni faces. When the streetcar takes off again, the little breeze that snakes its way past the salving girls is a drooly lick. A breeze almost worse than none. Ariel sighs and remembers woodsmoke, brown leaves dancing across a sidewalk. The people who have lived here their entire lives can’t have any idea what they’re missing.

She wonders what Ed will make for dinner. She wonders about her commitment to public transportation in a city like this.

Ed hollers hello from the kitchen. Miles and Ella bicker above the somber narration of Animal Planet surgery: “Lucky’s femur is broken in five places.” Ariel saves her breath. The instant she’d confront Ed about their children watching surgical gore is the instant he’d take the remote, change the channel, and say, “What gore? There. Look. PBS.” And smile. She’s given up on training him to greet her at the door with a martini.

“Changing!” Ariel yells, ascending the stairs. The house groans out its age with each footfall.

In September, cold water only runs cool. Ariel drops her head in the shower. She waits, knows that the water temperature won’t change, feels nostalgic, considers where, exactly, the best place is to apply a cold pack to drop body temperature. Wrist. Throat. Sliceable places. Once, in Jamaica, a man put shell-shaped ice chips in her vagina in some form of misdirected foreplay. The ice melted. Even then, young as she was, the island and the guy alike felt fake to her. Practiced. She tries to remember the guy’s name, knows she can’t, not even to save her life.

The soap rests in a soupy muck in the holder. Ish. If Ed is going to tend house, then that’s what he should do, but he just doesn’t see things. Giant snot soap. How do you miss it?

She should be fair. Ed cooks. Ed listens to NPR.

What’s His Name, the ice chip man, had a washboard stomach. Ariel didn’t come. She knew she wouldn’t the instant he stood at the end of the bed and caressed his own waxed chest in some staged, amorous gesture. She has no recollection of whether his was a name that suited him or not.

Names hold too much power, she thinks, or none at all. Everyone should have a chance to name themselves. Just today “Miss Sugar Enspice” checked into the hotel. Ariel recognized the woman with crispy yellow extensions from her music video, the one where her plump ass cheeks hang out the bottom of a pair of kiwi-colored shorts.

Jesus, some of the pseudonyms that the celebrity guests use. Axel Savage. Rod Doe. Ha! Everybody behind the front desk busted guts. Rod Doe. Nameless Cock. The pubescent musician had no clue, it seemed, as he gave her, the general manager, very specific instructions on who could and who could not know his room number, what calls could be put through. He took off his dark sunglasses, stared directly into Ariel’s eyes the way some men’s magazine must have told him to do, and said she could use his room number. She felt at once mildly flattered and sick to her stomach. His dyed black hair stood in carefully spaced spikes all over his puny head. Ariel nodded politely. She bet he had acne on his back.

The idiotic name of the hotel itself can’t be beat: La Belle Nouvelle, a Barcelona-modern hotel through and through smushed into the French Quarter at the edge of the Central Business District. They don’t even have enough curb footage on the street to get zoned for valet parking. The bulk of the property rises orange and lime green, a contemporary cyst, in the center of the block between a department store and three empty buildings being forever renovated, the continual drilling and pneumatic hammering deafening to everyone but touring bands and the feckless groupies for whom the hotel has become a favorite. Ooh, and she can’t forget the proms. Or the frat and sorority formals. Somehow, Ariel is supposed to change the clientele. A year ago April, when the new owners called Minneapolis and made the offer she couldn’t refuse, she thought the name La Belle Nouvelle was likely reflective of some sort of New Orleans charm she hadn’t yet experienced. Ah. Well.

Their own family’s names always hover, too. Fruit fly names that won’t leave. Ariel kept her surname when they married, and they gave it to their kids. Ed, fortunately, has always believed the decision to be best. But then Edgar Allan Flank is a toughie of a moniker. Ariel and Ed couldn’t break completely from family tradition though. They chose two classics for their children: Miles Davis May and Ella Fitzgerald May. Ella will answer to the nickname Fitzy when she has no choice. Drying off, walking naked into their warm bedroom, Ariel again hopes they haven’t burdened their children with expectations of greatness.

Fearius sit, full-up tired of patient. His ass sore, done molded to the car seat by now. Shandra and Alphonse fighting and fighting on her stoop. “I say I finish for seven!” she scream at him.

Alphonse dont care, mixed everything up. Now Fearius not gettin no Shandra friends pussy.

Alphonse got the Glock in his pants still, in there for hours. Fearius feel like his dick a gun, feel like shooting big old lumpy Shandra with her witchy claws that cost more than Dom Pérignon. Except Alphonse got the Glock, so Fearius not getting no fat Shandra neither.

Fearius decide to quit Alphonses company till tomorrow. Tonight Fearius gone make a girlfriend, no matter what, make sure no Glocks nearby.

It a hot night, time he make hisself a girlfriend in the Channel by Annunciation. Lots of them over there when it hot, clucking, all together on corners like hens. Bunch a chicken heads.

Kissin between houses can turn into a lay down in no time.

“The goopas are purple,” Ella says, kicking the table leg. Ariel’s daughter peels cheese from the top of her lasagna with her fingers. Her chipped nail polish has disappeared.

“Guptas,” Miles enunciates.

“What?” Ariel understands her kids less each day. She knows she should be frightened by this fact. “What are guptas?”

Miles, Ella, and Ed giggle. “Who,” Ed says. “They’re a who.”

“What?”

“Mah-um!”

“Ed?”

“We say ‘people of color,’ ” Ed instructs Ella, and Miles rolls his eyes. So does Ariel.

“Ed?”

“Uh huh.” Ella nods. “Dark dark purple.”

“Nah ah.”

The junior high people of color on the streetcar today gyrated in the aisle. Ariel tries to remember dancing at twelve. A table for twelve. A party of twelve. Here in this city she’s learned everybody says, about a time, I’ll be there for twelve. I have to be there for six. We need a reservation for nine for seven. In such instances, Ariel has yet to figure out which way they want the reservation. A bellhop told her it comes from the French, which automatically means it doesn’t make any sense to Ariel. Sadly, no matter what Ariel tries, La Belle Nouvelle’s high-end dinner-bar retains a reputation for serving underage drinkers.

The dancing kids filled the aisle. They seemed to want to rile people of non-color on the streetcar. Why did she have to be a non-color? She has color. “Ed?”

“Our new neighbors,” he answers.

“They’re Indian,” Miles says knowingly.

Ed lays his hand on the table in front of Miles’ plate. “We say East Indian,” Ed corrects. This from the man who didn’t notice his daughter chewing on the end of the grape magic marker till the ink had covered her entire front in a purple indelible apron. Now Ella’s favorite color seems to be a shade of Gupta.

“Where?” Ariel asks, meaning which house. Two houses on their street have sold recently, the big one immediately to their right and a little one across the street next to the ratty community garden.

“Next door!” Miles yells.

“Next door!” Ella echoes and kicks the table leg again. “Next door!”

Ariel looks to Ed to see what he thinks. “Real new neighbors, then,” she says. Ed, the local stay-at-home dad, keeps a close watch on the neighborhood. He recognizes everybody. He knows the names of the teenagers who live on the block. He waves hello to some of the afternoon regulars who frequent the neighborhood bar, Tokyo Rose. Sitting diagonally across the street from their house, the little ugly thing looks like a residential shack decked out in Christmas decorations year-round. She could kill the realtor for not pointing it out to her as an up-and-running bar when she flew down to check out properties, but then again, kudos to Numbnuts for fooling her. She didn’t think to ask about it, and he didn’t offer. Kudos to New Orleans too for burying its bars so well that outsiders don’t even recognize them sitting square in the middle of a neighborhood block.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Once in a great while, a novel comes along that makes you sit up and look around at your world and see it anew, in all its richness and complexity…. A brilliant, nuanced portrait of pre-Katrina New Orleans.” —The Times-Picayune “Set in the chaotic months surrounding a treacherous hurricane, Boyden's second novel is an adroit, compulsively readable study of a city and the shared humanity that unites its diverse inhabitants.” —People“Explores the fissures of class and race on a street where America's diversity is writ small. . . . She orchestrates the voices of her characters like a composer, well attuned to the varieties of human speech.” —Chicago Tribune “Boyden makes it sing. . . . The five story lines build into a terrifically vivid portrait of a city and its people.” —San Francisco Chronicle “Boyden has written a heartwreck of a novel, a luminous swan song for a time and a place.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch “Complex and compelling.... Boyden has so fully and generously imagined Orchid Street and its inhabitants. Her writing acknowledges the depth of race and class divisions... but she’s also aware of the ways people break out of their assigned roles.... From the stutter steps her characters take toward and away from one another, Boyden creates an engrossing dance.... The five story lines build into a terrifically vivid portrait of a city and its people.” —San Francisco Chronicle “Few contemporary novels are, at their root, as compelling about the relationship between a city and the people who live there. Boyden’s Babylon Rolling is a love letter, sometimes sad, sometimes angry, sometimes beautiful, between New Orleans and five people who live on one of its streets.” —The Globe and Mail (Toronto) “It is possible that New Orleans is the perfect setting for the post-9/11 American novel…. Like the characters in the gorgeous and tactile Babylon Rolling, our survival hinges on our ability to cope with the lack of a universal culture and common body politic, the truth that natural disasters and random violence are a fact of life.” —Mother Jones“Boyden's novel conveys the patchwork of New Orleans' Uptown neighborhoods–very much evident in Riverbend, where working-class whites and blacks live alongside old-line socialites and immigrant professionals. . . . Episodic but not predictable, it is a book that beckons to be read for just a few more pages.” —Mobile Press-Register “Threats of natural disaster bracket this novel of New Orleans, which opens just prior to Hurricane Ivan in September 2004 and ends with the ominous approach of Katrina the following summer. In the intervening year, certain residents of the Uptown district weather personal tragedies rivaling the impact of killer storms. Orchid Street, diverse by any standard, includes two African American families, upstanding senior citizens Roy and Cerise Brown and the more struggling Harrises, as well as a young family of well-meaning but clueless whites recently arrived from Minnesota, a half-mad gentlewoman of the old school, and the exotic, intellectual Gupta clan. Neighborhood bar Tokyo Rose serves all as both haven from and catalyst of neighborhood disturbances. As lives and cultures overlap, the author of Pretty Little Dirty melds an enticing sense of place and a kaleidoscope of distinctive voices into a cautionary tale of ambition, desire, and conflict.”—Library Journal"Boyden has a chameleon-like ability to inhabit any persona, of any race or age, so fully and seamlessly it's hard to remember that these people are invented rather than real. Pre-Katrina New Orleans leaps to life on every page, a beautiful, seamy, fragile city on the brink of chaos and ruin. Babylon Rolling is a heart-breaking and riveting novel."—Kate Christensen, author of The Great Man, winner of the 2008 PEN/Faulkner Award"Boyden invoked an array of New Orleans voices on Uptown's Orchid Street . . . an American Babylon that batters and woos with delights and disasters . . . The book's nuanced story of people who 'choose to live . . . inside the big lasso of river' reveals a side of the Crescent City not often seen in fiction."—Publishers Weekly“An engaging and keenly observant book, a kindv of literary block party.... Boyden’s Pretty Little Dirty was a first novel of promise. Babylon Rolling fulfills that promise.” —Booklist

Descriere

A glittering, gritty, and unflinching story of five families living along one block in New Orleans, "Babylon Rolling" is the tale of a year on Orchid Street, where lives collide and the humid air is charged with constant wanting.