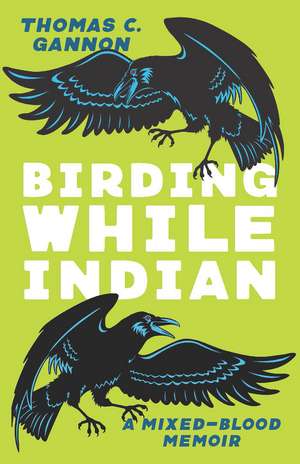

Birding While Indian: A Mixed-Blood Memoir: Machete

Autor Thomas C. Gannonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 27 iun 2023

Winner, 2024 Stubbendieck Great Plains Distinguished Book Prize “A fascinating search for personal and cultural identity.” —Kirkus Thomas C. Gannon’s Birding While Indian spans more than fifty years of childhood walks and adult road trips to deliver, via a compendium of birds recorded and revered, the author’s life as a part-Lakota inhabitant of the Great Plains. Great Horned Owl, Sandhill Crane, Dickcissel: such species form a kind of rosary, a corrective to the rosaries that evoke Gannon’s traumatic time in an Indian boarding school in South Dakota, his mother’s devastation at racist bullying from coworkers, and the violent erasure colonialism demanded of the people and other animals indigenous to the United States. Birding has always been Gannon’s escape and solace. He later found similar solace in literature, particularly by Native authors. He draws on both throughout this expansive, hilarious, and humane memoir. An acerbic observer—of birds, the environment, the aftershocks of history, and human nature—Gannon navigates his obsession with the ostensibly objective avocation of birding and his own mixed-blood subjectivity, searching for that elusive Snowy Owl and his own identity. The result is a rich reflection not only on one man’s life but on the transformative power of building a deeper relationship with the natural world.

Preț: 109.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 164

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.88€ • 21.80$ • 17.28£

20.88€ • 21.80$ • 17.28£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814258729

ISBN-10: 0814258727

Pagini: 2248

Ilustrații: 6 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Machete

ISBN-10: 0814258727

Pagini: 2248

Ilustrații: 6 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Machete

Recenzii

“Gannon takes us along on his journey through a part of the nation that is often ignored or misunderstood, and despite plenty of heartache and sorrow, he offers much-needed moments of levity. … Whether recounting his encounters with a great horned owl, sandhill crane, wood duck, field sparrow, bald eagle, white stork, or snowy egret, the author is consistently engaging and thoughtful about his place in a world that we share with a wondrous assortment of other species. A fascinating search for personal and cultural identity.” —Kirkus

“Lyrical and evocative … Gannon’s ruminations on his identity crisis hold undeniable power.” —Publishers Weekly

“Since time immemorial, Native people have looked for signs from avian beings, and here, Thomas Gannon carries on those traditions in his wry chronicles about growing up and living on the Great Plains. This is a much-needed and much-appreciated addition to Native literature. Birding While Indian is all that and a bag of tobacco.” —Tiffany Midge, author of Bury My Heart at Chuck E. Cheese’s

“Birding While Indian provides a thoughtful contribution to Native American and environmental studies. It deserves to be widely read, particularly as we battle the twin global crises of structural racism and environmental collapse … it’s an honest memoir with sensitive nature writing, a testimony to the non-human world’s ability to provide human solace.” —Glen Retief, River Teeth

“[Tracks] the devastating and far-reaching impacts of colonialism through an interweaving of history, philosophy, poetry and [Gannon’s] personal experiences with birds.” —Molly Adams, TheWashington Post

Notă biografică

Thomas C. Gannon is an associate professor of English and ethnic studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and a lifelong birder and inhabitant of the Great Plains. He is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.

Extras

MARCH 1965, PISS HILL: Great Horned Owl

I jumped off an Iowa City bridge into the Iowa River my freshman year of college because I had been reading too much William Blake and Walt Whitman and William Butler Yeats. I jumped because I was on an ROTC scholarship and I suddenly realized that I didn't want to have to go and kill anybody on behalf of a jingoistic nationalism that I already didn't believe in. I jumped because I was a mixed-up mixed-blood who had already grown tired of trying to figure out who the hell I was-white or Indian.

It may have all begun when my best friend in the fourth grade asked me, "Do you know that your mom's a squaw?" That's the moment I began my retreat from the cruel racial politics of western South Dakota by taking weekend birding excursions to the dark pine hills just on the edge of town. A SoDak Huck Finn with a lot more personal baggage, I only had to walk a few miles through the dilapidated housing of North Rapid City, climb a chain-link fence along the interstate that led out of town, dodge across the interstate traffic, walk a few more dilapidated blocks-and there I was, at the foothills of the beautiful Black Hills of South Dakota.

I called the first steep hill that I had to climb Piss Hill because that's what I usually did when I reached the top of it. When my younger brothers came along, that communal piss became a manly (however boyish) initiation ritual of Campbellian proportions, given the relative immensity of the hill-and perhaps the relatively small size of young boys' bladders. Then only a steep ravine of scattered small pines and yucca plants divided us from the next much more substantial pine hill, which was the actual goal of my bird ramblings. This was the primal Wordsworthian spot of ground of my formative years. There I honed my two-tone chickadee imitations-fee-bee, a whistled fall of a whole tone-and saw and heard for the first time a good majority of the bird species that made up the first fifty birds or so of my life list.

This was my home (away from a troubled home), where I could negotiate and navigate the contents of my grade-schooler consciousness, where I could map some order and reason onto my experiential universe. I needed something more "outside," less human, maybe: here I was beyond human borders and definitions.

"Do you know that your mom's a squaw?" No, I didn't want to know it, and maybe I was avoiding that self-recognition when I became that avid fourth-grade birder. After all, a Black-capped Chickadee was simply a Black-capped Chickadee.

But my will to order required some expenditure, and as the eldest boy of a single Indian woman on welfare, I couldn't buy such frivolities with food stamps. But there was Christmas, and I could also save my fifty-cents-a-month allowance; I could even interest my younger brothers in my hobby, thereby "borrowing" their allowances to procure the birding essentials that "we" needed. Our initial acquisition was that crucial first bird guide, Robbins, Bruun, and Zim's Birds of North America, about six bucks for the hardcover first edition. And the Christmas previous to my first Great Horned Owl brought me that essential pair of 7x35 binoculars, from K-Mart.

Years later, when I was a high school senior applying for admission to West Point, a well-wishing friend of my mom typed up a "LIST OF ACHIEVEMENTS OF TOM GANNON." One item read, "Started a neighborhood bird club and published an ornithological journal, which only lasted one issue, due to member apathy." What this sentence doesn't convey is that the "bird club" consisted of just me and my two younger brothers, and that the "journal" was a one-page fold job made up of a few amateurish paragraphs by me about the local birds and a few paragraphs probably copied out of one of my bird books, for the edification of the masses. Copies-for my brothers-were laboriously created by hand on carbon paper.

I jumped off an Iowa City bridge into the Iowa River my freshman year of college because I had been reading too much William Blake and Walt Whitman and William Butler Yeats. I jumped because I was on an ROTC scholarship and I suddenly realized that I didn't want to have to go and kill anybody on behalf of a jingoistic nationalism that I already didn't believe in. I jumped because I was a mixed-up mixed-blood who had already grown tired of trying to figure out who the hell I was-white or Indian.

It may have all begun when my best friend in the fourth grade asked me, "Do you know that your mom's a squaw?" That's the moment I began my retreat from the cruel racial politics of western South Dakota by taking weekend birding excursions to the dark pine hills just on the edge of town. A SoDak Huck Finn with a lot more personal baggage, I only had to walk a few miles through the dilapidated housing of North Rapid City, climb a chain-link fence along the interstate that led out of town, dodge across the interstate traffic, walk a few more dilapidated blocks-and there I was, at the foothills of the beautiful Black Hills of South Dakota.

I called the first steep hill that I had to climb Piss Hill because that's what I usually did when I reached the top of it. When my younger brothers came along, that communal piss became a manly (however boyish) initiation ritual of Campbellian proportions, given the relative immensity of the hill-and perhaps the relatively small size of young boys' bladders. Then only a steep ravine of scattered small pines and yucca plants divided us from the next much more substantial pine hill, which was the actual goal of my bird ramblings. This was the primal Wordsworthian spot of ground of my formative years. There I honed my two-tone chickadee imitations-fee-bee, a whistled fall of a whole tone-and saw and heard for the first time a good majority of the bird species that made up the first fifty birds or so of my life list.

This was my home (away from a troubled home), where I could negotiate and navigate the contents of my grade-schooler consciousness, where I could map some order and reason onto my experiential universe. I needed something more "outside," less human, maybe: here I was beyond human borders and definitions.

"Do you know that your mom's a squaw?" No, I didn't want to know it, and maybe I was avoiding that self-recognition when I became that avid fourth-grade birder. After all, a Black-capped Chickadee was simply a Black-capped Chickadee.

But my will to order required some expenditure, and as the eldest boy of a single Indian woman on welfare, I couldn't buy such frivolities with food stamps. But there was Christmas, and I could also save my fifty-cents-a-month allowance; I could even interest my younger brothers in my hobby, thereby "borrowing" their allowances to procure the birding essentials that "we" needed. Our initial acquisition was that crucial first bird guide, Robbins, Bruun, and Zim's Birds of North America, about six bucks for the hardcover first edition. And the Christmas previous to my first Great Horned Owl brought me that essential pair of 7x35 binoculars, from K-Mart.

Years later, when I was a high school senior applying for admission to West Point, a well-wishing friend of my mom typed up a "LIST OF ACHIEVEMENTS OF TOM GANNON." One item read, "Started a neighborhood bird club and published an ornithological journal, which only lasted one issue, due to member apathy." What this sentence doesn't convey is that the "bird club" consisted of just me and my two younger brothers, and that the "journal" was a one-page fold job made up of a few amateurish paragraphs by me about the local birds and a few paragraphs probably copied out of one of my bird books, for the edification of the masses. Copies-for my brothers-were laboriously created by hand on carbon paper.

Cuprins

Preface: The Lifelook March 1965, Piss Hill: Great Horned Owl July 1967, Piss Hill: Lewis's Woodpecker January 1968, Rapid Creek: Common Goldeneye June 1969, I-90: Western Meadowlark April 1970, Fort Pierre / Missouri River: Sandhill Crane June 1970, a Fort Pierre Slough: Wood Duck August 1971, Saskatchewan: Western Grebe May 1977, a Rapid City Marsh: Red-Winged Blackbird June 1978, Spearfish Canyon: American Dipper June 1979, a Pennington County Dirt Road: Common Nighthawk August 1981, Old Faithful: Common Raven June 1983, a Pennington County Dirt Road: Long-Billed Curlew June 1985, Skyline Drive: Field Sparrow June 1985, Fort Morgan, CO: House Finch September 1987, Northern Black Hills: Mourning Dove December 1987, Belle Fourche, SD: [Species Unknown] January 1989, Rapid City, SD: European Starling January 1991, Gavins Point Dam: Long-Tailed Duck April 2001, U of Iowa English-Philosophy Building: Common Grackle February 2003, Kirk Funeral Home: Prairie Falcon April 2003, U of Iowa English-Philosophy Building: Northern Cardinal May 2003, Clay County Park: Bald Eagle June 2004, Ardmore, OK: Northern Mockingbird June 2005, Folsom Children's Zoo: White Stork June 2006, Crazy Horse Memorial: Turkey Vulture July 2008, Kountze Lake: Snowy Egret August 2008, Fontenelle Forest: House Wren May 2009, the Lake beside Lakeside, NE: Black-Necked Stilt May 2009, Devils Tower: American Goldfinch May 2009, Little Bighorn Battlefield: Eurasian Collared-Dove May 2009, Bowdoin National Wildlife Refuge: Marbled Godwit July 2009, Pioneers Park: Brown-Headed Cowbird June 2010, Idyllwild, CA: Steller's Jay June 2010, Spirit Mound: Dickcissel May 2011, Wilderness Park: Veery December 2011, Highway 385: Ferruginous Hawk May 2012, Indian Cave State Park: Chuck-Will's-Widow June 2012, Custer State Park: Canyon Wren June 2012, Millwood State Park: Black-Bellied Whistling-Duck July 2012, Newton Hills State Park: Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker July 2012, Morrison Park: Lesser Goldfinch May 2013, Pawnee Lake State Recreation Area: Bonaparte's Gull May 2014, El Segundo Beach: Brown Pelican March 2015, Pawnee Lake State Recreation Area: American Robin July 2016, Medicine Bow National Forest-Vedauwoo: Dusky Flycatcher November 2017, Lewis and Clark Lake: Snowy Owl March 2018, West Platte River Drive: Whooping Crane May 2018, Little Bighorn Battlefield: Red-Tailed Hawk Coda: Birding While Indian

Descriere

Catalogs a lifetime of bird sightings to explore the part-Lakota author’s search for identity and his reckoning with colonialism’s violence against Indigenous humans, animals, and land.