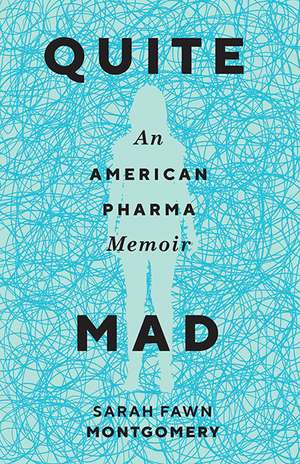

Quite Mad: An American Pharma Memoir: Machete

Autor Sarah Fawn Montgomeryen Limba Engleză Paperback – 20 sep 2018

Diagnosed with severe anxiety, PTSD, and OCD in her early twenties, Sarah Fawn Montgomery spent the next ten years seeking treatment and the language with which to describe the indescribable consequences of her mental illness. Faced with disbelief, intolerable side effects, and unexpected changes in her mental health as a result of treatment, Montgomery turned to American history and her own personal history—including her turbulent childhood and the violence she faced as a young woman—to make sense of the experience.

Blending memoir with literary journalism, Montgomery’s Quite Mad: An American Pharma Memoir examines America’s history of mental illness treatment—lobotomies to sterilization, the rest cure to Prozac—to challenge contemporary narratives about mental health. Questioning what it means to be a woman with highly stigmatized disorders, Montgomery also asks why mental illness continues to escalate in the United States despite so many “cures.” Investigating the construction of mental illness as a “female” malady, Montgomery exposes the ways current attitudes towards women and their bodies influence madness as well as the ways madness has transformed to a chronic Illness in our cultural imagination. Montgomery’s Quite Mad is one woman’s story, but it offers a beacon of hope and truth for the millions of individuals living with mental illness and issues a warning about the danger of diagnosis and the complex definition of sanity.

Blending memoir with literary journalism, Montgomery’s Quite Mad: An American Pharma Memoir examines America’s history of mental illness treatment—lobotomies to sterilization, the rest cure to Prozac—to challenge contemporary narratives about mental health. Questioning what it means to be a woman with highly stigmatized disorders, Montgomery also asks why mental illness continues to escalate in the United States despite so many “cures.” Investigating the construction of mental illness as a “female” malady, Montgomery exposes the ways current attitudes towards women and their bodies influence madness as well as the ways madness has transformed to a chronic Illness in our cultural imagination. Montgomery’s Quite Mad is one woman’s story, but it offers a beacon of hope and truth for the millions of individuals living with mental illness and issues a warning about the danger of diagnosis and the complex definition of sanity.

Preț: 181.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 272

Preț estimativ în valută:

34.74€ • 37.75$ • 29.20£

34.74€ • 37.75$ • 29.20£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 17-23 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814254868

ISBN-10: 0814254861

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Machete

ISBN-10: 0814254861

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Machete

Recenzii

“To cover so much material could have resulted in an unwieldy book, but Montgomery’s keen curiosity guides us through history, social criticism, and the author’s lived experience.…Quite Mad joins several recent works…which, thankfully, seem to be working toward new ways of writing about mental health.”

—Melissa Oliveira, Brevity

—Melissa Oliveira, Brevity

“A wrenching account of a difficult upbringing and a chaotic brain that will leave readers marveling at the author's endurance. . . . The author offers a gripping picture of the real pain and suffering of someone diagnosed with chronic mental illness.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Montgomery puts American denial on display, describing why we label mental illness so paradoxically: ‘to talk of disease without cure is problematic for a country concerned with triumph.’ As a country we choose to pop pills instead of accepting the difficult aspects of human existence, medicating ourselves into oblivion. Quite Mad is the wake-up call that we need.” —Madeline Day, Paris Review

“Sarah Fawn Montgomery’s Quite Mad is a brilliant, kinetic story of living with anxiety disorder. She captures both her inner struggles and her outer ones, taking control of both herself and the clinicians who put patient needs last. An essential book.” —Susanne Paola Antonetta, author of A Mind Apart

“Quite Mad is at once a well-organized history of mental illness, especially with regard to women, an examination of the role of the illness narrative, and a fascinating memoir of a woman’s struggle.” —Intima

"An important and incredible debut work of nonfiction, a powerful consideration of our collective thinking about mental health, and a heartfelt unflinching memoir of her own personal fight against misunderstanding and overmedication.” —Steven Church, author of I’m Just Getting to the Disturbing Part

Notă biografică

Sarah Fawn Montgomery is the author of Regenerate: Poems of Mad Women, Leaving Tracks: A Prairie Guide, and The Astronaut Checks His Watch. She works as Prairie Schooner’s Assistant Nonfiction Editor and is an Assistant Professor at Bridgewater State University in Massachusetts.

Extras

Prologue

I’m on my knees again, like I was an hour ago and the hour before that. Like I’ve been each day for the past few months since I first arrived here. Here is a large brick building in the middle of a college campus, in the middle of America. Here is where I am teaching and earning a PhD. Here makes people widen their eyes, impressed by the “Dr.” they will eventually include before my name, but mostly by the way my job doesn’t have nine-to-five hours or summers.

Here is also the third stall of a bathroom on the third floor where I run several times a day to throw up, shaking and sweating, my head spinning with thoughts of cancer or brain disease, thoughts that an asteroid is heading towards Earth, or that my cat was right when she looked at me funny this morning, stretched her paws, and told me today was the day I would die.

If I hear someone come in—esteemed professor of this, distinguished writer of that—I pause. I try to think really hard, to focus, to hold what little breath I have and bear down on my teeth and tense every muscle in my body. I pull myself in stiff like a reed. It’s not that I don’t want them to know I’m here—it’s that if I don’t hold taut and still, all dread and dead, eyes and mouth pinched shut, I won’t be able to stop heaving and gasping. I won’t be able to function as I should, won’t be able to go about my day smiling and nodding. I won’t be able to keep pretending.

The truth: I’m throwing up because this is what I do lately when I hear students outside, their voices interrupting one another, or planes overhead, sirens racing through the intersection, the professor in his office next to mine eating lunch, pop of lid, crunch of can, ringing telephone. This is what I do lately when I see the news—floods and famines, chemicals and cancers, children murdering their parents, parents murdering their children, all interrupted by celebrity gossip and lifestyle reports. Lately I throw up every time I leave the house. Sometimes I feel so sick I think the planes are going to bomb somewhere, think the sirens are racing for me like I don’t know what’s wrong yet, think the news reports are broadcasting warnings from the future. I think the neighbors I can hear fighting through the walls of my apartment might fire a gun and that the bullet might arc directly down into my skull, blazing across my sight with a white hot light. Fear tingles in my limbs like a premonition.

I have generalized anxiety disorder, which means I live a socially stigmatized existence ruled by chronic fear and worry, my stress over lack of sleep or bills or work twisting itself in my psyche until it manifests as constant distress, irritability, restlessness, catastrophic paranoia, and strange delusions.

Sometimes I have panic attacks, feelings of terror that come on suddenly, peaking within a few minutes, but whose symptoms—palpations and chest pain some liken to a heart attack, trembling and sweating, the feeling of being smothered or choked, nausea, lightheadedness, numbness and tingling, chills and hot flashes, the fear of losing control, the sense of impeding death, a detachment from reality and my body—last several hours and leave me with the lingering fear of having another attack, a worry that often brings on several more.

I was twenty-two the first time I had a panic attack. One night I took two ibuprofen and quickly became convinced I’d swallowed a handful. A burn enveloped my body, I lost my breath, my limbs went dead, and even though I felt trapped in the chaos, I also seemed to be floating above the scene, disconnected from the moment, powerless to stop whatever was seeping through me, building speed until it surged. I grew hysterical, pacing the house, hyperventilating and sweating, eventually cowering in a cold shower. Afraid to sleep after the attack, I spent much of the night retching and crying, gnarled fingers clutching at my unreliable heart. The attacks continued the next day and in the weeks after, building in frequency until I began experiencing them each night, waking up in a cold sweat unable to breathe, crying out as I clawed at my chest.

Ever since, I’ve had attacks that stem from mundane things—driving by a car accident causes catastrophic thoughts of my own mortality, a thunderstorm brings about thoughts of electrocution’s fantastic fireworks making my body fluorescent, unusually sore muscles leads to thoughts of cancer creeping through my body like a blush. Coming up the stairs and finding myself out of breath triggers a fear that I’m having an attack, and my body follows suit. It’s mostly miserable, irritatingly irrational, entirely inexplicable.

I’m afraid of dying a lot these days, so I retreat to bathrooms, bathtubs, the floor, trying to make the world disappear by focusing on the toilet, the shower stall, a bit of fuzz on the carpet. It’s like I think that focusing intensely on some small detail will help me forget my fear of future destruction. But then again, focusing on tiny details—a cough, a bump on my shin I’d never noticed before—is how the madness starts in the first place.

I’m on my knees again, like I was an hour ago and the hour before that. Like I’ve been each day for the past few months since I first arrived here. Here is a large brick building in the middle of a college campus, in the middle of America. Here is where I am teaching and earning a PhD. Here makes people widen their eyes, impressed by the “Dr.” they will eventually include before my name, but mostly by the way my job doesn’t have nine-to-five hours or summers.

Here is also the third stall of a bathroom on the third floor where I run several times a day to throw up, shaking and sweating, my head spinning with thoughts of cancer or brain disease, thoughts that an asteroid is heading towards Earth, or that my cat was right when she looked at me funny this morning, stretched her paws, and told me today was the day I would die.

If I hear someone come in—esteemed professor of this, distinguished writer of that—I pause. I try to think really hard, to focus, to hold what little breath I have and bear down on my teeth and tense every muscle in my body. I pull myself in stiff like a reed. It’s not that I don’t want them to know I’m here—it’s that if I don’t hold taut and still, all dread and dead, eyes and mouth pinched shut, I won’t be able to stop heaving and gasping. I won’t be able to function as I should, won’t be able to go about my day smiling and nodding. I won’t be able to keep pretending.

The truth: I’m throwing up because this is what I do lately when I hear students outside, their voices interrupting one another, or planes overhead, sirens racing through the intersection, the professor in his office next to mine eating lunch, pop of lid, crunch of can, ringing telephone. This is what I do lately when I see the news—floods and famines, chemicals and cancers, children murdering their parents, parents murdering their children, all interrupted by celebrity gossip and lifestyle reports. Lately I throw up every time I leave the house. Sometimes I feel so sick I think the planes are going to bomb somewhere, think the sirens are racing for me like I don’t know what’s wrong yet, think the news reports are broadcasting warnings from the future. I think the neighbors I can hear fighting through the walls of my apartment might fire a gun and that the bullet might arc directly down into my skull, blazing across my sight with a white hot light. Fear tingles in my limbs like a premonition.

I have generalized anxiety disorder, which means I live a socially stigmatized existence ruled by chronic fear and worry, my stress over lack of sleep or bills or work twisting itself in my psyche until it manifests as constant distress, irritability, restlessness, catastrophic paranoia, and strange delusions.

Sometimes I have panic attacks, feelings of terror that come on suddenly, peaking within a few minutes, but whose symptoms—palpations and chest pain some liken to a heart attack, trembling and sweating, the feeling of being smothered or choked, nausea, lightheadedness, numbness and tingling, chills and hot flashes, the fear of losing control, the sense of impeding death, a detachment from reality and my body—last several hours and leave me with the lingering fear of having another attack, a worry that often brings on several more.

I was twenty-two the first time I had a panic attack. One night I took two ibuprofen and quickly became convinced I’d swallowed a handful. A burn enveloped my body, I lost my breath, my limbs went dead, and even though I felt trapped in the chaos, I also seemed to be floating above the scene, disconnected from the moment, powerless to stop whatever was seeping through me, building speed until it surged. I grew hysterical, pacing the house, hyperventilating and sweating, eventually cowering in a cold shower. Afraid to sleep after the attack, I spent much of the night retching and crying, gnarled fingers clutching at my unreliable heart. The attacks continued the next day and in the weeks after, building in frequency until I began experiencing them each night, waking up in a cold sweat unable to breathe, crying out as I clawed at my chest.

Ever since, I’ve had attacks that stem from mundane things—driving by a car accident causes catastrophic thoughts of my own mortality, a thunderstorm brings about thoughts of electrocution’s fantastic fireworks making my body fluorescent, unusually sore muscles leads to thoughts of cancer creeping through my body like a blush. Coming up the stairs and finding myself out of breath triggers a fear that I’m having an attack, and my body follows suit. It’s mostly miserable, irritatingly irrational, entirely inexplicable.

I’m afraid of dying a lot these days, so I retreat to bathrooms, bathtubs, the floor, trying to make the world disappear by focusing on the toilet, the shower stall, a bit of fuzz on the carpet. It’s like I think that focusing intensely on some small detail will help me forget my fear of future destruction. But then again, focusing on tiny details—a cough, a bump on my shin I’d never noticed before—is how the madness starts in the first place.

Descriere

A young woman’s fiercely vulnerable memoir about seeking cure and speaking truth in the midst of America’s mental health crisis.