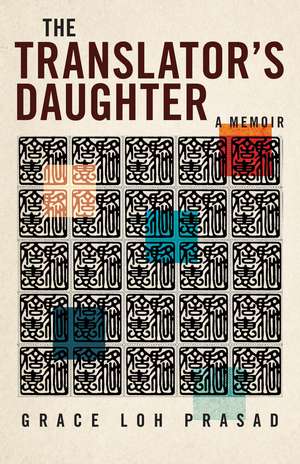

The Translator's Daughter: A Memoir: Machete

Autor Grace Loh Prasaden Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 mar 2024 – vârsta ani

Born in Taiwan, Grace Loh Prasad was two years old when the threat of political persecution under Chiang Kai-shek's dictatorship drove her family to the United States, setting her up to become an accidental immigrant. The family did not know when they would be able to go home again; this exile lasted long enough for Prasad to forget her native Taiwanese language and grow up American. Having multilingual parents—including a father who worked as a translator—meant she never had to develop the fluency to navigate Taiwan on visits. But when her parents moved back to Taiwan permanently when she was in college and her mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer's, she recognized the urgency of forging a stronger connection with her birthplace before it was too late. As she recounts her journey to reclaim her heritage in The Translator's Daughter, Prasad unfurls themes of memory, dislocation, and loss in all their rich complexity. The result is a unique immigration story about the loneliness of living in a diaspora, the search for belonging, and the meaning of home.

Preț: 132.81 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 199

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.42€ • 26.44$ • 20.98£

25.42€ • 26.44$ • 20.98£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814258972

ISBN-10: 0814258972

Pagini: 268

Ilustrații: 11 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Machete

ISBN-10: 0814258972

Pagini: 268

Ilustrații: 11 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Machete

Recenzii

"A compelling and poignant story that sheds light on Taiwanese culture and recent history. Essential for readers interested in Taiwan in specific or immigration memoirs in general." —Joshua Wallace, Library Journal

"The product of two decades of work, this moving memoir by Bay Area writer Grace Loh Prasad explores a life lived in-between: split by family migrations from Taiwan to the United States and back again, divided by languages and bonds lost and found." —Hannah Bae, San Francisco Chronicle

“Prasad’s memoir is a tender tribute to her multilingual parents and a sensitive evocation of life as part of the Asian diaspora.” —Katie Noah Gibson, Shelf Awareness

“Grace Loh Prasad interrogates the distance between the homes we have and the homes we long for with the compassion and precision of one who has spent her entire life attuned to language. ‘We were always half a world apart,’ she writes; her essays bridge that gap in innovative ways, using family photos, mythical women, and Taiwanese films. Moving fluidly between the personal and the political, this memoir is a remarkable addition to Taiwanese American literature.” —Jami Nakamura Lin, author of The Night Parade

“Grace Loh Prasad’s debut memoir, The Translator’s Daughter, is a delicately wrought reckoning with her Taiwanese identity and its dependence on her parents. … Prasad writes with quiet confidence as she probes her past.” —Priyanka Champaneri, Washington Independent Review of Books

“The Translator’s Daughter is a soulful and profound meditation on family, diaspora, and grief. How do we construct a life far away from our loved ones, and what do we lose? How do we preserve all that we have been given? Grace Loh Prasad tackles these questions with honesty and beauty, while also illuminating Taiwan’s culture, history, and hard-won path to democracy. I savored this book.” —Michelle Kuo, author of Reading with Patrick

“The Translator's Daughter is a stunning tribute to the complexities of growing up as a third-culture kid, an honest and moving chronicle of the ‘abundance and loss’ of living across languages and continents.” —Shawna Yang Ryan, author of Green Island

“You can really feel the two decades Prasad put into this memoir. This is careful, considered prose and thought from a writer to both anticipate and learn from. A marvelous debut.” —Matthew Salesses, author of The Sense of Wonder

Notă biografică

Grace Loh Prasad writes frequently on the topics of diaspora and belonging. Her writing has been published in the New York Times, Longreads, The Offing, Hyperallergic, Catapult, Ninth Letter, KHÔRA, and elsewhere. She is a member of The Writers Grotto and Seventeen Syllables, an Asian American Pacific Islander writers’ collective. She lives in the Bay Area.

Extras

From “The Year of the Dragon: Part 1”

Upstairs in the departure lounge, it’s a different world. It feels like walking from a library into a casino—everything is louder, brighter, in motion. Suddenly I’m surrounded by cigarette smoke and cell phone conversations and overstuffed duty-free bags. Middle-aged men in suits and young women carrying designer handbags swarm around me. Everyone is moving—either leaving or arriving. In an hour, all these people will be gone and replaced by another wave of travelers. More coming, more going.

At the nearest gift shop, I ask the cashier if I can buy a phone card. She points me to an old lady sitting at a counter at the back of the store. I walk back there and point to the phone cards on display under the glass. I hold up two fingers. The old lady, a plump grandma with short gray hair and dark penciled-in eyebrows, looks at me and says a few words in Mandarin. I shrug. She smiles and repeats her words in Taiwanese, but I still don’t know what she’s saying, so I say in English, “Sorry, I don’t understand.” She gives a little laugh and a sigh, not seeming to mind.

“You wan’ phone ca?”

“Yes. Two cards.”

“Okay.” She mumbles something in Taiwanese and walks away for a minute while I get my wallet. She comes back holding a large, individually wrapped almond cookie, the kind you get as an airplane snack.

“You take!” She hands it to me with the two phone cards and smiles. I smile back, embarrassed by her kindness. I think of my own grandma and her unconditional affection toward me despite the language barrier. Perhaps this woman has a daughter or granddaughter living overseas too. Perhaps she knows, without explanation, the distance I’ve traveled to be here.

Even though my parents live only a few miles away, we’re separated by a gaping, unbridgeable distance. I had expected to see them in three dimensions upon landing here on this side, but except for a brief glimpse that morning, they’ve just been voices on the end of a phone line, shadows in another time zone. Or maybe I’m the one who’s a shadow. We live on opposite sides of the globe, leading mostly separate lives, yet I take for granted that I can simply get on a plane and come over here and insert myself into this reality. I’ve gone back and forth so many times that I should know what to expect, and yet the transition has never felt so . . . off.

I’ve never spent time in Taiwan when I wasn’t with my parents. They always mediate and translate for me. Without them, I lose the context I’ve always depended on for my visits. They’re the only way I can connect with anything here—my relatives, the language and customs, the insider’s knowledge of the city. The little bit of independence that I have—walking around Sanhsia or taking the bus alone to certain parts of Taipei—is based on observation, repetition, and the growing usage of English signs. But I still can’t order my own food in a restaurant, let alone deal with a hostile bureaucracy without assistance. I never imagined I might have to learn to navigate Taiwan on my own. What would I do if my parents weren’t here to bail me out? How would I communicate? Who would I call for help?

I go back to the transit lounge and sit in one of the hard cold plastic chairs. Now that my passport is on its way, there is nothing to do but wait. It’s nearly 1:00 p.m.

My mouth is dry, and I’m dying for a mint, a stick of gum, anything to change the stale taste in my mouth. I need a shower badly. My hair is greasy, and my face is flaky from the dry air and constant re-powdering. I wish I had worn something warmer than a thin sweater and unlined pants. I could change my clothes, since I have my bags with me, but I didn’t bring anything heavier. How ironic, because I felt so good about packing light this time—one jacket, two pairs of shoes, and a few wrinkle-proof outfits for a week in Taiwan. I’ve made this trip often enough to be able to pare down to the essentials. Only this time, I forgot something important.

The sky looks like it’s getting a little darker outside, though it’s hard to tell for sure because of the fluorescent lighting. This room has had the same unearthly glow since 6:00 a.m. The 747s glide back and forth outside the window, each arrival corresponding with an announcement. Osaka . . . Guam . . . Denpasar. Each aircraft disgorges its unseen human cargo, signaled by a crescendo of voices and the unmistakable sound of wheeled suitcases being dragged on linoleum. A sea of bodies moves toward Immigration, and the voices drift away as quickly as they came.

For a few hours, Henry Park keeps me company. I gratefully lose track of the time and try to forget my situation and surroundings by immersing myself in the book Native Speaker by Chang-rae Lee. In Henry I find a kindred spirit, another immigrant tormented by the language left behind: “When I step into a Korean dry cleaner, or a candy shop, I always feel I’m an audience member asked to stand up and sing with the diva, that I know every pitch and note but can no longer call them forth.”

Like Henry, who works as a spy, I’ve somehow managed to infiltrate my native culture without actually taking part in it. I can feign the appearance of belonging until my speech—or lack of it—gives me away. No amount of sincerity can make up for this defect, this flaw that separates me from the people I ought to consider as my own.

At the nearest gift shop, I ask the cashier if I can buy a phone card. She points me to an old lady sitting at a counter at the back of the store. I walk back there and point to the phone cards on display under the glass. I hold up two fingers. The old lady, a plump grandma with short gray hair and dark penciled-in eyebrows, looks at me and says a few words in Mandarin. I shrug. She smiles and repeats her words in Taiwanese, but I still don’t know what she’s saying, so I say in English, “Sorry, I don’t understand.” She gives a little laugh and a sigh, not seeming to mind.

“You wan’ phone ca?”

“Yes. Two cards.”

“Okay.” She mumbles something in Taiwanese and walks away for a minute while I get my wallet. She comes back holding a large, individually wrapped almond cookie, the kind you get as an airplane snack.

“You take!” She hands it to me with the two phone cards and smiles. I smile back, embarrassed by her kindness. I think of my own grandma and her unconditional affection toward me despite the language barrier. Perhaps this woman has a daughter or granddaughter living overseas too. Perhaps she knows, without explanation, the distance I’ve traveled to be here.

Even though my parents live only a few miles away, we’re separated by a gaping, unbridgeable distance. I had expected to see them in three dimensions upon landing here on this side, but except for a brief glimpse that morning, they’ve just been voices on the end of a phone line, shadows in another time zone. Or maybe I’m the one who’s a shadow. We live on opposite sides of the globe, leading mostly separate lives, yet I take for granted that I can simply get on a plane and come over here and insert myself into this reality. I’ve gone back and forth so many times that I should know what to expect, and yet the transition has never felt so . . . off.

I’ve never spent time in Taiwan when I wasn’t with my parents. They always mediate and translate for me. Without them, I lose the context I’ve always depended on for my visits. They’re the only way I can connect with anything here—my relatives, the language and customs, the insider’s knowledge of the city. The little bit of independence that I have—walking around Sanhsia or taking the bus alone to certain parts of Taipei—is based on observation, repetition, and the growing usage of English signs. But I still can’t order my own food in a restaurant, let alone deal with a hostile bureaucracy without assistance. I never imagined I might have to learn to navigate Taiwan on my own. What would I do if my parents weren’t here to bail me out? How would I communicate? Who would I call for help?

I go back to the transit lounge and sit in one of the hard cold plastic chairs. Now that my passport is on its way, there is nothing to do but wait. It’s nearly 1:00 p.m.

My mouth is dry, and I’m dying for a mint, a stick of gum, anything to change the stale taste in my mouth. I need a shower badly. My hair is greasy, and my face is flaky from the dry air and constant re-powdering. I wish I had worn something warmer than a thin sweater and unlined pants. I could change my clothes, since I have my bags with me, but I didn’t bring anything heavier. How ironic, because I felt so good about packing light this time—one jacket, two pairs of shoes, and a few wrinkle-proof outfits for a week in Taiwan. I’ve made this trip often enough to be able to pare down to the essentials. Only this time, I forgot something important.

The sky looks like it’s getting a little darker outside, though it’s hard to tell for sure because of the fluorescent lighting. This room has had the same unearthly glow since 6:00 a.m. The 747s glide back and forth outside the window, each arrival corresponding with an announcement. Osaka . . . Guam . . . Denpasar. Each aircraft disgorges its unseen human cargo, signaled by a crescendo of voices and the unmistakable sound of wheeled suitcases being dragged on linoleum. A sea of bodies moves toward Immigration, and the voices drift away as quickly as they came.

For a few hours, Henry Park keeps me company. I gratefully lose track of the time and try to forget my situation and surroundings by immersing myself in the book Native Speaker by Chang-rae Lee. In Henry I find a kindred spirit, another immigrant tormented by the language left behind: “When I step into a Korean dry cleaner, or a candy shop, I always feel I’m an audience member asked to stand up and sing with the diva, that I know every pitch and note but can no longer call them forth.”

Like Henry, who works as a spy, I’ve somehow managed to infiltrate my native culture without actually taking part in it. I can feign the appearance of belonging until my speech—or lack of it—gives me away. No amount of sincerity can make up for this defect, this flaw that separates me from the people I ought to consider as my own.

Cuprins

Author’s Note Year of the Dragon, Part 1 Album Gaining Face Year of the Dragon, Part 2 The Pig Festival Projections Seasons of Scrabble and Mahjong Going Home Vortex Another Incident A Seed Doesn’t Choose Where It Falls Allegories Last Time in Bangkok Unbridgeable What David Bowie Taught Me about Art, Death, and Letting Go Double Life Mooncake Feathers from Home and Other Family Heirlooms Uncertain Ground The Orca and the Spider: On Motherhood, Loss, and Community A Book from the Sky Unfinished Translation One Day You’ll Need This Acknowledgments

Descriere

A Taiwanese American writer unfurls themes of memory, dislocation, language, and loss to tell a unique story about reclaiming one's heritage while living in a diaspora.