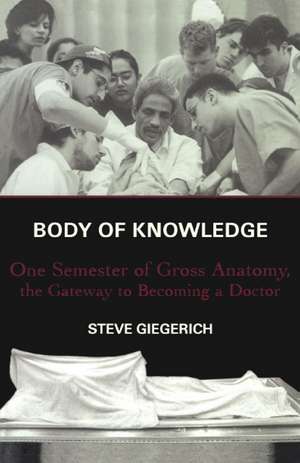

Body of Knowledge: One Semester of Gross Anatomy, the Gateway to Becoming a Doctor

Autor Steven Giegerichen Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 aug 2002

Four lab partners facing that notoriously difficult course at Newark's University of Medicine and Dentistry are Sherry Ikalowych, a former nurse and mother of four; Jennifer Hannum, an ultracompetitive jock; Udele Tagoe, a determined Duke graduate of Ghanian descent; and Ivan Gonzalez, a Nicaraguan refugee and unlikely medical student. This lively chronicle of each of their ambitions, failures, and successes has at its center Tom Lewis, the cadaver lying before them to be dissected. From their first face-to-face encounter with Lewis as an anonymous cadaver on the stainless steel table to a rich reverence for Lewis's generous donation of his body to science, what they each learn about medicine, compassion, life, and death makes for a fascinating insiders' account of the shaping of a medical professional.

Preț: 103.75 lei

Preț vechi: 109.21 lei

-5% Nou

Puncte Express: 156

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.86€ • 20.44$ • 16.74£

19.86€ • 20.44$ • 16.74£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 07-21 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780684862088

ISBN-10: 0684862085

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0684862085

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Steve Giegerich is a journalist and a member of the adjunct faculty at the Columbia University School of Journalism. A Pulitzer Prize finalist in 1998, he resides in Locust, New Jersey.

Extras

Chapter One

At mid-morning on Tuesday, April 1, 1997, a late-model station wagon, ordinary but for the smoked glass obscuring its rear windows, turned from South Orange Avenue into the main entrance of the New Jersey Medical School parking lot. From the driveway, the car made a hard left, descending immediately down a ramp leading to a submerged loading dock.

Because the height of the dock accommodated trucks, not cars, the driver parked off to the side. Unlatching the tailgate, he slid his delivery from the vehicle. Workers in another venue might have been unsettled by what emerged from the cargo hold, but in this environment no one paid the slightest attention. Here, dead bodies were a matter of course. Every day, someone was either coming -- into the embalming room operated under the supervision of the NJMS anatomy department -- or going -- the dock also served as the dispatch point for undertakers retrieving the deceased from the medical school's sister institution, Newark's University Hospital.

Once the collapsible gurney was removed from the station wagon, the driver clicked the stretcher into position and wheeled it up a foot ramp and through a set of automatic metal doors warning away all but authorized personnel. Inside the building, he approached a second authorized personnel only sign, where he pressed the buzzer outside a brown, windowless metal door.

Twenty seconds later, the door swung open. "Got one for you," said the driver, handing a folder to a stocky man in his early sixties with the erect posture of a military veteran. The driver, an employee of Funeral Service of New Jersey, a company dedicated to the transportation of human remains, ignored a surge of air redolent with chemicals. Pulling the gurney behind him, he entered a room cast in drab institutional yellow, its purpose distinguished by two stainless-steel cribs with drainage basins, each flanked by a pair of fifty-five-gallon chemical drums. In the corner, next to a third table, stood a fixed eighteen-inch single-blade jigsaw.

Roger Faison accepted the folder and tossed it onto a countertop. Excusing himself, Faison returned to the room a moment later with a medical school stretcher onto which he and the driver transferred the body. Plucking a receipt from the folder, Faison signed it and slipped it to the driver, who was on his way out the door within five minutes of arrival.

Faison thumbed absently through the folder and considered his schedule. It was a slow week; the students were gone, as were most of the faculty. Along with the medical researchers and support staff, Faison usually remained behind during spring break. He didn't mind staying put. In fact, he rather liked having the place more or less to himself, if for no other reason than it decreased the number of emergencies, real and imagined, requiring his immediate attention.

Through the years, Faison had used the respite to catch up on paperwork and other assorted tasks that tended to be pushed aside while, in the laboratory one floor above, the first-year students were enmeshed in the medical school initiation known as Gross and Developmental Anatomy. From January through April -- desiring to acclimate the students to the rigors of medical education early, NJMS, unlike the majority of medical schools, scheduled the mandatory gross anatomy curriculum during the second semester -- chaos was the order of the day, every day. The pandemonium would resume the following Monday; until then, Faison set the pace. He put off the embalming until Wednesday.

Faison wheeled the gurney into a walk-in refrigerator. One hundred eighty-five corpses, most wrapped in clear plastic bags, lay inside. All but ten rested on open-shelved compartments arranged in a grid twenty-five rows across and seven rows deep. The most recent arrivals were on gurneys, a temporary arrangement until space on the grid became available.

Embalming bodies for a medical school was not what Roger Faison had in mind when, in 1957, he applied his GI bill toward a degree in mortuary science. He had emerged from the navy a firm believer in the American dream, believing "all that crap that I read about economics in magazines about how if you work hard, the world is yours." In Faison's case, this meant becoming the owner and operator of the best funeral home in the Brooklyn neighborhood where he grew up, Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Fresh out of mortuary school, he landed an apprenticeship and began to expand himself academically. Understanding that mortuary wasn't the only science he'd need in order to make a name for himself in the funeral industry, Faison enrolled at Fordham University. Four years later, he departed with a degree in economics.

A submariner at the height of the cold war, Faison's navy stint only heightened his sense of adventure. In the navy, there had been exhilaration in spending weeks tracking Soviet submarines below ocean surfaces. In business, the thrill came in the pursuit of financial success.

Traditionally, in small towns across America and especially in the South, the black community revolved around the churches and the mortuary. The local undertaker was a professional, a man of dignity and grace, a man who, before civil rights laws prevailed to change the scope of race relations, served as the nominal link between his community and the prevailing white power structure. Brooklyn, which, in the early 1960s, still prided itself on being the biggest small town in America, was no different. With a gentle demeanor that masked a droll sense of humor, Faison settled into the niche. His business took off. Bed-Stuy brought him its dead; he, in turn, provided compassion and understanding, services he brought with him also to Manhattan's Upper West Side after borrowing the money to open a second parlor there.

Back in Brooklyn, a borough with a population larger than all but a handful of the country's biggest cities, Faison conceived a plan he hoped would appeal to the huge untapped market residing in Bed-Stuy's tenements and housing projects. Knowing a funeral could be arranged for far below the going rate, $1,000, Faison launched a marketing campaign, papering the projects with leaflets guaranteeing a complete funeral, sans burial expenses, for $500. Citing a law prohibiting such a blatant form of advertising, state regulators told him to knock it off. The competition took an even dimmer view, twice phoning bomb threats to Faison's mortuary within an hour of a scheduled funeral. Faison took the hint and reverted to the standard fee assessed by the city's other mortuaries.

Economics, the very subject he'd gone out of his way to master, proved to be his downfall. When, in the early 1980s, conglomerates began buying up New York mortuaries en masse, Faison refused to sell and gamely tried to compete. With the advantage of volume economics, the bigger companies eventually undercut the competition; in other words, the same economic theory that two decades before had brought Faison bomb threats was now turned against him. In 1986 he gave up, sold the funeral homes, paid off the banks and moved to New Jersey and a job immune to the trials imposed by the free-market system.

Embalming at NJMS brought with it a different set of predicaments. In the private sector, embalming emphasized presentation -- the undertaker's objective, on behalf of the deceased, was to create a lifelike appearance engineered to last for the intervening period between death and burial. At the medical school, aesthetics went out the door; preservation became paramount. Faison no longer cared what the bodies looked like; his only concern was to ward off decomposition. The bodies in a Gross and Developmental Anatomy laboratory had to last fourteen weeks lest Faison incur the wrath of faculty and students alike.

Each year, at their own request, the donated bodies of nearly a hundred men and women were transported to the basement of the ten-story NJMS medical science building, located in the heart of Newark's Central Ward. Of that number, slightly more than half ended up in the anatomy lab: forty-five to be dissected by medical students, another twenty-five dissected by students attending the adjoining institution, the New Jersey School of Dentistry, ten to fifteen more to train surgical residents and a handful beyond that deployed to assist qualified surgeons in the development of new surgical procedures and techniques.

Bodies that didn't go to the laboratory normally wound up in the university's medical research wings. While some donors requested their remains be channeled to researchers with a specific area of expertise, most placed no restrictions. The decision about placement was usually Faison's. His was a simple formula: Bodies dispatched to the gross anatomy laboratory had to merit an "AA rating." Meaning a lean body, not prone to decay.

Preventing decomposition became all the more difficult when, two years after Faison came to NJMS, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) showed up for a routine inspection of the first-floor gross anatomy laboratory, four windowless rooms with dropped ceilings. Citing poor air quality and substandard ventilation, the agency declared the formaldehyde used to preserve the dead to be hazardous to the living and ordered the school to shut down the lab. The action, halfway through the semester, triggered a spate of appeals from the school administration to a bureaucratic entity that dictated that the lab doors remain locked until Faison came up with an alternative to formaldehyde as an embalming solution.

The government regulators, however, failed to take into account the perseverance of the students. Undeterred, they began showing up at the lab in the wee hours of the morning. Employing the hammers and chisels issued them for the purposes of dissection, they unhinged the doors and went about their task nocturnally. The school looked the other way. When the faculty, support personnel and OSHA monitors arrived the next morning, the doors were again hinged and locked.

As the students pursued their course of study by night, Faison spent his days grilling chemists, funeral home directors and medical school embalmers across the country for answers. Faison's mission -- to find a low-toxicity chemical with long-term preservation qualities -- tested the creativity of the best minds in chemistry and the mortuary sciences. Finally, two weeks after they first locked the doors, Faison proposed to OSHA that formaldehyde be substituted with a concentration of phenol, alcohol and glycerin. The compound smelled as bad as formaldehyde, and there were no guarantees that it would preserve a human body over fourteen weeks, but with the administration and anatomy faculty breathing down his neck, Faison had no other choice. To the relief of all, the agency accepted.

Because the cadavers in the lab were already embalmed with formaldehyde, a compromise was reached to allow the resumption of the semester: Permitting the lab to reopen, OSHA stipulated that its representatives be present for the weeks remaining in the academic term to monitor toxicity levels. For the rest of the semester, the students and faculty worked with overhead measurement booms, similar to those used by television news crews. The students resented the intrusion, and though the booms over the tables were an irritating distraction, they felt they gained a measure of retribution in the obvious discomfort that the OSHA team had with the lab's primary activity.

Despising the substitute compound, Faison never again embalmed with formaldehyde. That OSHA subsequently forced other medical schools to switch to phenol did nothing to allay his consternation. Especially when a counterpart at an Ivy League institution gloated, "You guys just don't have enough clout." Faison knew it to be true: Among the prestigious medical schools lining the Northeast Corridor from Boston to Washington, NJMS was pretty much relegated to the status of poor cousin.

Ten years after the OSHA crackdown, Faison still struggled to find an adequate level of phenol-glycerin to keep the cadavers viable. Using weight as a criterion, most of the time he guessed correctly. The X factor was metabolism. There was no way to know which bodies would most effectively metabolize the compound and which would begin to decompose the moment they were removed from the refrigeration unit.

Before OSHA, Faison took pride in his embalming. In the years after, the caliber of his work became a source of embarrassment: "When we used formaldehyde these bodies were standing tall and right. Now, halfway through the semester, I'm ashamed. Just ashamed."

Governmental interference notwithstanding, the medical school provided Faison with a secure environment. Unencumbered by obligations to lending institutions, Faison no longer had to worry about the competition. With money no longer a factor, an unexpected dividend emerged: the students. Fascinated by their swagger, confidence and how, despite some unbelievable setbacks, they always bounced back, Faison loved interacting with them. Their youthful optimism was contagious, and best of all, every year a new batch arrived -- filled with just as much brio as the class before.

The downside of academia resided in office politics. Faison, with a front-row seat for the internecine squabbles both inside and outside the anatomy department, had never seen anything like it. The anatomists blamed the cell and tissue biology faculty for inadequately preparing the students for anatomy; the senior surgical fellows pointed the finger at the anatomists for not fulfilling their obligations to the students. On and on it went. Within the anatomy department every decision, be it by administrator or faculty, triggered endless second-guessing. "Sometimes it amazes me that anyone ever learns anything here," said one anatomy instructor, who added, "Against all odds, though, it happens."

Faison may have witnessed firsthand the endemic political infighting, but he also had a place to escape: a refuge seven floors below the academic battlefield on the G level, home of the NJMS Department of Anatomy.

The first thing Roger Faison did upon arriving at his sanctum early on the morning of April 2, 1997, was to remove from the refrigerator the body that had arrived the previous day. Maintained at a constant temperature of 34 degrees, the refrigerator preserved the integrity of capillaries that would otherwise collapse should the thermal reading inside the unit drop below freezing.

With the assistance of Dr. David Abkin, a former Russian surgeon who in addition to operating the anatomy lab supply room also served as Faison's assistant, the mortician shifted the body from the gurney onto one of the stainless-steel basins. While the refrigerator was kept warm enough to prevent the deterioration of veins and arteries, its algidity nonetheless dictated a ten-hour thawing before the onset of embalming.

At four o'clock that afternoon, Faison slipped a Miles Davis CD into his boom box and returned to the body. Peeling back the sheet covering the head, the mortician made a three-inch incision in the right side of the neck. From the top of the chemical barrel, he retrieved and fit hypodermic needles onto the ends of two rubber tubes. He inserted one needle into the right common carotid artery, the other into the right internal jugular vein. Faison flicked a switch and, above the table, a pump began to rumble, the fifty-five-gallon drum started to gulp. The mortician watched as the phenol-glycerin trickled through the tube attached to the common carotid artery, causing blood to simultaneously drain from the second tube into a barrel marked for medical waste.

Ninety minutes later, when the fluid emerging from the drainage tube ran clear, devoid of blood, Faison switched off the pump. Removing the needles from the neck and then the tubing, he inserted them in a red medical-waste box, and he returned to the body, where he tied shut the incision with heavy-gauge embalmer's thread.

Faison moved to the foot of the body, removed the toe tag and checked the name on the tag against the paperwork brought by the funeral service driver: Lewis. He tossed aside the tag and retrieved a translucent orange bracelet from a box on the counter. A number had been written on the bracelet with a Magic Marker: 3426. Faison scribbled the number across the front of the folder and fastened the bracelet around the cadaver's left ankle.

The mortician flipped through the paperwork and began dividing it into two piles. Most of it -- the death certificate, information about notifying the next of kin once the ashes became available -- he earmarked for Essie Feldman's office on G level. For his own files, Faison copied a few documents and placed them in an office cabinet. Faison scanned the obituary tucked into the folder and learned the man he'd just embalmed had been an educator. A teacher, Faison thought, very appropriate. He placed the obit back in the folder; on a copy of the receipt left by the funeral service, he noted: "Good subject. Possible Medical Gross."

Abkin helped Faison place the body in a large, clear plastic bag. They transferred Number 3426 to the gurney, which Faison then wheeled back into the refrigerator, officially designated on the building registrar as Room A526B.

On the wall above the clutter of folders, memorandums, written requests for donor forms, half-finished letters, partially completed syllabuses and other academic flotsam littering Essie Feldman's work area hung an enlarged photocopy declaring: "A Clean Desk Is a Sign of a Sick Mind." That being the case, Feldman was the picture of mental health.

The morning following the embalming, Faison deposited Number 3426's folder atop the pile and spent a few moments with Feldman catching up on the latest gossip. All anatomy department scuttlebutt passed through Feldman, whose ebullience -- everyone, save the department chairman, Dr. John H. Siegel, received the same salutation, "honey" -- penetrated the gravitas that permeated the halls of medical education. Flighty in personality and stylish in dress, Feldman stood out in a recondite atmosphere where grave demeanors were as common as white lab coats. Given her personality, Essie Feldman would, on the surface, seem an unlikely liaison between the medical school and the general public when it came to a topic most people are loath to discuss: death and its aftermath.

Feldman hadn't been predisposed to counsel the living about that which would transpire after they died; instead, the position chose her. In 1969, Feldman first reported for duty at the medical school in the capacity of secretary, and to the payroll department, a secretary she would remain during a tenure that would eventually exceed thirty years.

On Essie Feldman's first day on the job, the New Jersey College of Medicine, as it was then known, had been operational barely two years. The school was the offspring of the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry, which, in 1956, had the distinction of being New Jersey's first medical school. Several reasons have been advanced as to why New Jersey didn't have a school of medicine until the last half of the twentieth century, the most popular being that it took that long for the state's legislators to reject antivivisection statutes imposed by their Puritan political forebears. For whatever reason, New Jersey politicians believed laws designed to prevent the mutilation of animals applied also to the dissection of human cadavers.

Academically and also by the real barometer used to evaluate the success of medical schools -- securing federal grant money -- Seton Hall was an unqualified success. Its Jersey City campus, perched on the Hudson River overlooking the Manhattan skyline, proved to be a magnet for leading researchers, many of whom abandoned the epicenter of U.S. medical research -- Boston -- to join the fledgling school. Unfortunately, the school's bottom line did not match its achievements in the classroom and laboratory. Start-up costs far exceeded expectations, and even the federal grants couldn't stave off the fiscal reality of operating a medical school. It didn't take long for the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry, under the domain of the Catholic university in South Orange bearing the same name, to realize its books would never balance. By the early 1960s, the school started casting for a benefactor to bail it out; five years later Seton Hall's knight arrived in the form of the State of New Jersey.

The team undertaking the state's first order of business, finding a site to relocate the campus, settled on a 150-acre estate in yet-to-be-suburbanized Morris County. Located in the northwest quadrant of the state, the property offered everything but an ethnically diverse employment pool. Exploiting Morris County's shortcoming, Newark's Democratic mayor Hugh Addonizio presented the Democratically controlled state legislature with an alternative: a city with an existing ethnic workforce to staff a major medical school and hospital complex and, for the campus's construction, contracts that would provide jobs for thousands of laborers represented by the unions that greased the wheels of New Jersey Democratic machine politics. To make room for the medical school and hospital, Addonizio promised to condemn 150 acres in the Central Ward, just west of downtown.

The state legislature may have embraced Addonizio's plan, but not so the one thousand men, women and children residing within the boundaries of those six square impoverished and crime-infested city blocks. They stood to lose their homes. In July of 1967, as Addonizio's recommendation moved closer to reality, their anger, aggravated by multiple other factors, exploded into three nights of mayhem that left twenty-six dead.

Two months later, a medical school that didn't want to be there welcomed its first class of students to a neighborhood that didn't want them. Many years passed before the Central Ward accepted the school and medical center, and despite outreach programs that in 1994 earned it an Outstanding Community Service Award from the American Association of Medical Colleges, to this day the resentment among some residents continues to run so deep that they profess to prefer dying in an ambulance en route to Beth Israel Hospital, five miles away, than accept treatment at the UMDNJ-University Hospital in their own backyard.

The relocation to Newark cost the medical school dearly. Much of the faculty abandoned the institution, and with them went federal research funds and burgeoning prestige.

Among those making the move from Jersey City to Newark was a young and theatrical anatomy instructor named Anthony Boccabella. A self-described "hotshot," Boccabella tended to pepper his lectures with double entendres. Given the subject, the possibilities were endless. He was no less flamboyant outside the classroom, boasting of being the first medical student ever to arrive at the University of Iowa piloting his own plane. Later, while serving in the joint capacity of administrator and instructor at NJMS, he obtained a law degree, a pursuit he credited to being made to feel like a black sheep in a family of lawyers.

In 1971, a year after the New Jersey Medical School was folded into the statewide system of health education facilities now known as the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Boccabella became the chairman of the anatomy department. He would have preferred to focus on his field of expertise, endocrinology, the study of the thyroid, pituitary and other endocrine glands. Still, he appreciated the value of anatomy as the basic foundation of medical school and medical practice. "The rest is just dressing," he fondly pointed out.

During its brief tenure, Seton Hall suffered no shortage of cadavers. Boccabella recalled that most "were not there voluntarily," a polite way of saying the bodies had been secured from morgues. When the state uprooted the Jersey City facility, the corpses were brought to Newark along with desks, examining tables and other amenities crucial to the teaching of medicine.

The surplus no longer existed by the time Boccabella took over the program. Then, as now, four to one is the accepted ratio of medical students to cadavers in domestic human anatomy labs, and rarely in U.S. schools are more than four students assigned to a table. At some European schools, the students aren't quite as fortunate, with eight or more assigned to a single table. More unfavorable are the conditions in European countries that lack an adequate system for securing bodies, a situation which dictates that instructors dissect while students are relegated to the role of spectators. In the United States, Boccabella observed, students get "hands-on experience. They're able to play with it, cut through it and learn from the body. We're very, very lucky in this country."

In 1971, the dearth of cadavers in Newark nearly forced Boccabella to adopt the European custom. At each table, six medical students and one dental student worked on a single cadaver. The dental students dissected the head; the medical students studied the rest of the body. With the situation reaching the "crisis" stage, Boccabella undertook a desperate move.

Inspired by medical science's advances in the field of transplantation, Americans were just becoming aware of organ donations. As a scientist, Boccabella knew of an active registry in Washington listing the names of men and women who wished to donate, postmortem, their corneas. Playing a hunch, Boccabella contacted the registry. If these people were willing to pledge their corneas, he reasoned, perhaps they'd be amenable to contributing their entire bodies. A "gracious and unthinking" clerk provided Boccabella with precisely what he desired: the names of ten thousand New Jerseyans on the registry. Before the year was out, all ten thousand received from Boccabella a "passionate" letter.

Simultaneous to dispatching the letter, Boccabella began making the rounds of the state's burial societies, organizations of senior citizens banded together to minimize the high cost of death. He started his speech with an appeal to altruism, calling the donation of a body a gift in perpetuity, an unselfish act of ultimate benefit to every man, woman and child healed by the physician who profited from its myriad lessons. Boccabella assured his audience that in the lab they would be granted complete anonymity. Neither faculty nor students would know their identities. Boccabella followed the entreaty with an offer he hoped they'd find difficult to refuse: a postdissection cremation paid in full by the State of New Jersey. After cremation, he promised the ashes would be returned to the families for disposal as they saw fit.

From Sussex County, in the farthest corner of the state, to Cape May, New Jersey's southernmost point, Boccabella delivered his spiel. On the power of personality, he soon had people discussing openly a subject previously avoided or dealt with surreptitiously.

His name became a euphemism, a punch line: A husband and wife who jointly willed their bodies to NJMS used to joke it was time to "call Dr. Boccabella" whenever one of them was laid low by a cold or other assorted minor maladies.

As often as not, Boccabella could count on at least two or three burial society members to bring an attractive next of kin to a meeting. Recently divorced and constantly on the make, Boccabella sought them out after his presentation to inquire if they'd enjoyed his discourse. Those responding in the affirmative received a donor application; those who filled it out on the spot risked subjecting themselves to the doctor sidling up and whispering: "I already own your body and I promise to take care of it, so why wait?"

One of the worst pickup lines in history notwithstanding, Boccabella's sales pitch had the desired effect. The donor application forms that began to trickle in soon reached flood level. Unable to handle the flow, the department chair turned to his secretary.

Essie Feldman, with no training in medicine and no experience dealing with the imminence of death, received from Boccabella cursory instructions on how to respond to prospective donors. Feldman turned out to be such a natural that, before long, she was in charge of the cadaver procurement program.

The job required a gentle touch and Essie Feldman had it. She became expert at the art of reassurance, especially, as was often the case, when a donor had second thoughts about his or her decision. In most cases it was a loved one who gave donors pause, not so much spouses -- a surprising number of husbands and wives submitted donor forms in tandem -- as sons and daughters. Children seemed to have the most difficulty wrapping their minds around the idea of what became of a human body donated to science. Sometimes Feldman spoke directly with the conflicted party and explained, as best she could, the program's importance. Usually, the appeal worked; when it didn't, Feldman cast no aspersions. It's important, she'd tell those withdrawing their names from the donor file, that everyone in the family be comfortable with the decision.

Although contact between Feldman and donors was limited almost entirely to mail and telephone, a personal relationship sometimes developed between a benefactor and the woman to whom he or she had entrusted his or her body. They'd relay news of weddings and births and anniversaries. One man sent vacation snapshots from ports of call around the world. "Maybe I'll see you soon, Essie!" he'd scribble jokingly across the back of the photos. After he died, his family invited Feldman to his memorial service. She attended.

Essie Feldman's job also brought with it a fair amount of sadness. The task she performed was the result of a decision predicated on an issue troublesome to contemplate -- human beings tend to shy away from considerations of what lies beyond this mortal coil -- and even more difficult to articulate. Still, after a time, Feldman noticed a trend: Most of the donors were college-educated, and according to handwritten addenda or notations on the forms, the majority also participated actively in mainstream religions.

Occasionally, she'd speak with a man or woman who expressed the wish that by making a donation someone else would be spared some level of pain and suffering. One afternoon she took a call from a woman who, in a halting voice, detailed a twenty-year battle with schizophrenia. "Have you any interest in examining a broken mind?" she inquired. Feldman assured the woman -- in her late thirties, she was far younger than the people who usually contacted Feldman -- that her gift would be routed to scientists conducting neurological research. The woman began to weep and then regained her composure. "Thank you, thank you," she said quietly. "I don't want what happened to me to happen to anyone else."

Of course, Feldman's life was not always the stuff of high drama. Most of the time, her workload filled the description ascribed to the job by the payroll department. In the eyes of the State of New Jersey, which paid her salary, Essie Feldman was a secretary. Meaning a good portion of each day was devoted to routinely filing paperwork submitted by men and women who'd made a remarkable and difficult decision.

Such was the case on April 3, 1997, when Roger Faison walked into her office and plopped Number 3426's folder on the ever-present stack of papers atop her desk. Later that day, after Feldman entered on the filing tab the name of the deceased and the number assigned to the cadaver, she dutifully placed the folder in a file cabinet. There, Number 3426's dossier would remain until Feldman received word from Faison that the body, by either advancing medical science through research or serving as an anatomical blueprint for a quartet of medical students, was being dispatched to the crematorium.

Upon the return of the remains to the medical school, Feldman would swing into action again, contacting the family, informing them to soon expect a package the size of a shoe box. On average, two years passed between the time NJMS received a body and the follow-up letter from Essie Feldman. A lot can happen in two years: Next of kin occasionally move without providing a forwarding address; older relatives often join their loved ones in death. Stubbornly determined, Feldman went to great lengths in the effort to find someone, anyone, to properly disperse the ashes, in one instance devoting six years to the search for a sole, surviving son. She finally located him in the Midwest.

The ashes of the men and women whose relatives eluded Feldman's dragnet were stacked four high on a shelved rack in a hallway outside Faison's office in the basement. When the number of boxes approached two hundred, Faison transported them to a Linden cemetery for interment in a special plot overseen by the medical school. For years, Faison had urged the administration to commemorate the site with a small marker acknowledging the gift of those interred there, and finally, in 1999, the school accommodated him.

For eighty-nine weeks, Number 3426 remained in the refrigeration unit. In early December 1998, Faison started to review his files, setting aside those marked "Possible Medical Gross." In choosing bodies for Medical Gross and Developmental Anatomy, Faison knew what he was looking for: the elusive "AA" ratings. And Number 3426 fit the bill.

Six days before Christmas, Faison and Abkin removed Number 3426 from the refrigerator and placed the body on a stainless-steel tray measuring thirty inches by seventy-five inches, aerated at the bottom by twenty-eight drainage holes. Placing the tray on a gurney, Faison and Abkin covered Number 3426 from head to toe with five frayed towels and wheeled the gurney onto a freight elevator located just outside the entrance to the embalming room. When the gurneys in the elevator numbered three, Faison turned his key and pushed the button marked B. At the B level, the doors opened into the supply room attached to the gross anatomy laboratory serving the students of the New Jersey Medical School.

The NJMS laboratory is actually four interconnected laboratories, lettered A, B, C, D, each with eleven dissection tables. Lab A is tucked off by itself. The other three form an inverted F. Along the spine of the F are light boxes, a place where the study of the dead is supplemented by photographic representations of the living: X rays, magnetic resonance images (MRIs) and CAT scans.

With a dropped ceiling, fluorescent lighting and no windows, the gross anatomy lab is mundane, sterile. No art adorns the walls. Only the orange storage cabinets and the stained orange and yellow cushions on the rolling chairs clumped around the dissection tables break the monotony of the room's dominant color, off-white.

The tables, $3,800 new, stand forty-two inches high when the hoods are pulled back and secured below the table. When the hood is closed, it raises the height of the table to sixty inches. Anyone looking at the five-sided beveled hood would know precisely what lies inside.

By the afternoon of December 19, Faison and Abkin were half finished with their task. With the tables in Labs A and B already occupied, they began filling Lab C. Two at a time, they took the three gurneys from the elevator through Lab B into Lab C. Number 3426 was wheeled by Faison to the last table in the first row of the room.

Joined by Abkin, Faison counted to three and the two men lifted the tray onto Table 26. Wordlessly, Faison shut the hood and began pushing the gurney back to the elevator. Eighteen AA-rated bodies remained in the basement. Roger Faison checked his watch and did a quick calculation: Six more trips, and then, finally, he could begin his Christmas break.

Copyright © 2001 by Steve Giegerich

At mid-morning on Tuesday, April 1, 1997, a late-model station wagon, ordinary but for the smoked glass obscuring its rear windows, turned from South Orange Avenue into the main entrance of the New Jersey Medical School parking lot. From the driveway, the car made a hard left, descending immediately down a ramp leading to a submerged loading dock.

Because the height of the dock accommodated trucks, not cars, the driver parked off to the side. Unlatching the tailgate, he slid his delivery from the vehicle. Workers in another venue might have been unsettled by what emerged from the cargo hold, but in this environment no one paid the slightest attention. Here, dead bodies were a matter of course. Every day, someone was either coming -- into the embalming room operated under the supervision of the NJMS anatomy department -- or going -- the dock also served as the dispatch point for undertakers retrieving the deceased from the medical school's sister institution, Newark's University Hospital.

Once the collapsible gurney was removed from the station wagon, the driver clicked the stretcher into position and wheeled it up a foot ramp and through a set of automatic metal doors warning away all but authorized personnel. Inside the building, he approached a second authorized personnel only sign, where he pressed the buzzer outside a brown, windowless metal door.

Twenty seconds later, the door swung open. "Got one for you," said the driver, handing a folder to a stocky man in his early sixties with the erect posture of a military veteran. The driver, an employee of Funeral Service of New Jersey, a company dedicated to the transportation of human remains, ignored a surge of air redolent with chemicals. Pulling the gurney behind him, he entered a room cast in drab institutional yellow, its purpose distinguished by two stainless-steel cribs with drainage basins, each flanked by a pair of fifty-five-gallon chemical drums. In the corner, next to a third table, stood a fixed eighteen-inch single-blade jigsaw.

Roger Faison accepted the folder and tossed it onto a countertop. Excusing himself, Faison returned to the room a moment later with a medical school stretcher onto which he and the driver transferred the body. Plucking a receipt from the folder, Faison signed it and slipped it to the driver, who was on his way out the door within five minutes of arrival.

Faison thumbed absently through the folder and considered his schedule. It was a slow week; the students were gone, as were most of the faculty. Along with the medical researchers and support staff, Faison usually remained behind during spring break. He didn't mind staying put. In fact, he rather liked having the place more or less to himself, if for no other reason than it decreased the number of emergencies, real and imagined, requiring his immediate attention.

Through the years, Faison had used the respite to catch up on paperwork and other assorted tasks that tended to be pushed aside while, in the laboratory one floor above, the first-year students were enmeshed in the medical school initiation known as Gross and Developmental Anatomy. From January through April -- desiring to acclimate the students to the rigors of medical education early, NJMS, unlike the majority of medical schools, scheduled the mandatory gross anatomy curriculum during the second semester -- chaos was the order of the day, every day. The pandemonium would resume the following Monday; until then, Faison set the pace. He put off the embalming until Wednesday.

Faison wheeled the gurney into a walk-in refrigerator. One hundred eighty-five corpses, most wrapped in clear plastic bags, lay inside. All but ten rested on open-shelved compartments arranged in a grid twenty-five rows across and seven rows deep. The most recent arrivals were on gurneys, a temporary arrangement until space on the grid became available.

Embalming bodies for a medical school was not what Roger Faison had in mind when, in 1957, he applied his GI bill toward a degree in mortuary science. He had emerged from the navy a firm believer in the American dream, believing "all that crap that I read about economics in magazines about how if you work hard, the world is yours." In Faison's case, this meant becoming the owner and operator of the best funeral home in the Brooklyn neighborhood where he grew up, Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Fresh out of mortuary school, he landed an apprenticeship and began to expand himself academically. Understanding that mortuary wasn't the only science he'd need in order to make a name for himself in the funeral industry, Faison enrolled at Fordham University. Four years later, he departed with a degree in economics.

A submariner at the height of the cold war, Faison's navy stint only heightened his sense of adventure. In the navy, there had been exhilaration in spending weeks tracking Soviet submarines below ocean surfaces. In business, the thrill came in the pursuit of financial success.

Traditionally, in small towns across America and especially in the South, the black community revolved around the churches and the mortuary. The local undertaker was a professional, a man of dignity and grace, a man who, before civil rights laws prevailed to change the scope of race relations, served as the nominal link between his community and the prevailing white power structure. Brooklyn, which, in the early 1960s, still prided itself on being the biggest small town in America, was no different. With a gentle demeanor that masked a droll sense of humor, Faison settled into the niche. His business took off. Bed-Stuy brought him its dead; he, in turn, provided compassion and understanding, services he brought with him also to Manhattan's Upper West Side after borrowing the money to open a second parlor there.

Back in Brooklyn, a borough with a population larger than all but a handful of the country's biggest cities, Faison conceived a plan he hoped would appeal to the huge untapped market residing in Bed-Stuy's tenements and housing projects. Knowing a funeral could be arranged for far below the going rate, $1,000, Faison launched a marketing campaign, papering the projects with leaflets guaranteeing a complete funeral, sans burial expenses, for $500. Citing a law prohibiting such a blatant form of advertising, state regulators told him to knock it off. The competition took an even dimmer view, twice phoning bomb threats to Faison's mortuary within an hour of a scheduled funeral. Faison took the hint and reverted to the standard fee assessed by the city's other mortuaries.

Economics, the very subject he'd gone out of his way to master, proved to be his downfall. When, in the early 1980s, conglomerates began buying up New York mortuaries en masse, Faison refused to sell and gamely tried to compete. With the advantage of volume economics, the bigger companies eventually undercut the competition; in other words, the same economic theory that two decades before had brought Faison bomb threats was now turned against him. In 1986 he gave up, sold the funeral homes, paid off the banks and moved to New Jersey and a job immune to the trials imposed by the free-market system.

Embalming at NJMS brought with it a different set of predicaments. In the private sector, embalming emphasized presentation -- the undertaker's objective, on behalf of the deceased, was to create a lifelike appearance engineered to last for the intervening period between death and burial. At the medical school, aesthetics went out the door; preservation became paramount. Faison no longer cared what the bodies looked like; his only concern was to ward off decomposition. The bodies in a Gross and Developmental Anatomy laboratory had to last fourteen weeks lest Faison incur the wrath of faculty and students alike.

Each year, at their own request, the donated bodies of nearly a hundred men and women were transported to the basement of the ten-story NJMS medical science building, located in the heart of Newark's Central Ward. Of that number, slightly more than half ended up in the anatomy lab: forty-five to be dissected by medical students, another twenty-five dissected by students attending the adjoining institution, the New Jersey School of Dentistry, ten to fifteen more to train surgical residents and a handful beyond that deployed to assist qualified surgeons in the development of new surgical procedures and techniques.

Bodies that didn't go to the laboratory normally wound up in the university's medical research wings. While some donors requested their remains be channeled to researchers with a specific area of expertise, most placed no restrictions. The decision about placement was usually Faison's. His was a simple formula: Bodies dispatched to the gross anatomy laboratory had to merit an "AA rating." Meaning a lean body, not prone to decay.

Preventing decomposition became all the more difficult when, two years after Faison came to NJMS, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) showed up for a routine inspection of the first-floor gross anatomy laboratory, four windowless rooms with dropped ceilings. Citing poor air quality and substandard ventilation, the agency declared the formaldehyde used to preserve the dead to be hazardous to the living and ordered the school to shut down the lab. The action, halfway through the semester, triggered a spate of appeals from the school administration to a bureaucratic entity that dictated that the lab doors remain locked until Faison came up with an alternative to formaldehyde as an embalming solution.

The government regulators, however, failed to take into account the perseverance of the students. Undeterred, they began showing up at the lab in the wee hours of the morning. Employing the hammers and chisels issued them for the purposes of dissection, they unhinged the doors and went about their task nocturnally. The school looked the other way. When the faculty, support personnel and OSHA monitors arrived the next morning, the doors were again hinged and locked.

As the students pursued their course of study by night, Faison spent his days grilling chemists, funeral home directors and medical school embalmers across the country for answers. Faison's mission -- to find a low-toxicity chemical with long-term preservation qualities -- tested the creativity of the best minds in chemistry and the mortuary sciences. Finally, two weeks after they first locked the doors, Faison proposed to OSHA that formaldehyde be substituted with a concentration of phenol, alcohol and glycerin. The compound smelled as bad as formaldehyde, and there were no guarantees that it would preserve a human body over fourteen weeks, but with the administration and anatomy faculty breathing down his neck, Faison had no other choice. To the relief of all, the agency accepted.

Because the cadavers in the lab were already embalmed with formaldehyde, a compromise was reached to allow the resumption of the semester: Permitting the lab to reopen, OSHA stipulated that its representatives be present for the weeks remaining in the academic term to monitor toxicity levels. For the rest of the semester, the students and faculty worked with overhead measurement booms, similar to those used by television news crews. The students resented the intrusion, and though the booms over the tables were an irritating distraction, they felt they gained a measure of retribution in the obvious discomfort that the OSHA team had with the lab's primary activity.

Despising the substitute compound, Faison never again embalmed with formaldehyde. That OSHA subsequently forced other medical schools to switch to phenol did nothing to allay his consternation. Especially when a counterpart at an Ivy League institution gloated, "You guys just don't have enough clout." Faison knew it to be true: Among the prestigious medical schools lining the Northeast Corridor from Boston to Washington, NJMS was pretty much relegated to the status of poor cousin.

Ten years after the OSHA crackdown, Faison still struggled to find an adequate level of phenol-glycerin to keep the cadavers viable. Using weight as a criterion, most of the time he guessed correctly. The X factor was metabolism. There was no way to know which bodies would most effectively metabolize the compound and which would begin to decompose the moment they were removed from the refrigeration unit.

Before OSHA, Faison took pride in his embalming. In the years after, the caliber of his work became a source of embarrassment: "When we used formaldehyde these bodies were standing tall and right. Now, halfway through the semester, I'm ashamed. Just ashamed."

Governmental interference notwithstanding, the medical school provided Faison with a secure environment. Unencumbered by obligations to lending institutions, Faison no longer had to worry about the competition. With money no longer a factor, an unexpected dividend emerged: the students. Fascinated by their swagger, confidence and how, despite some unbelievable setbacks, they always bounced back, Faison loved interacting with them. Their youthful optimism was contagious, and best of all, every year a new batch arrived -- filled with just as much brio as the class before.

The downside of academia resided in office politics. Faison, with a front-row seat for the internecine squabbles both inside and outside the anatomy department, had never seen anything like it. The anatomists blamed the cell and tissue biology faculty for inadequately preparing the students for anatomy; the senior surgical fellows pointed the finger at the anatomists for not fulfilling their obligations to the students. On and on it went. Within the anatomy department every decision, be it by administrator or faculty, triggered endless second-guessing. "Sometimes it amazes me that anyone ever learns anything here," said one anatomy instructor, who added, "Against all odds, though, it happens."

Faison may have witnessed firsthand the endemic political infighting, but he also had a place to escape: a refuge seven floors below the academic battlefield on the G level, home of the NJMS Department of Anatomy.

The first thing Roger Faison did upon arriving at his sanctum early on the morning of April 2, 1997, was to remove from the refrigerator the body that had arrived the previous day. Maintained at a constant temperature of 34 degrees, the refrigerator preserved the integrity of capillaries that would otherwise collapse should the thermal reading inside the unit drop below freezing.

With the assistance of Dr. David Abkin, a former Russian surgeon who in addition to operating the anatomy lab supply room also served as Faison's assistant, the mortician shifted the body from the gurney onto one of the stainless-steel basins. While the refrigerator was kept warm enough to prevent the deterioration of veins and arteries, its algidity nonetheless dictated a ten-hour thawing before the onset of embalming.

At four o'clock that afternoon, Faison slipped a Miles Davis CD into his boom box and returned to the body. Peeling back the sheet covering the head, the mortician made a three-inch incision in the right side of the neck. From the top of the chemical barrel, he retrieved and fit hypodermic needles onto the ends of two rubber tubes. He inserted one needle into the right common carotid artery, the other into the right internal jugular vein. Faison flicked a switch and, above the table, a pump began to rumble, the fifty-five-gallon drum started to gulp. The mortician watched as the phenol-glycerin trickled through the tube attached to the common carotid artery, causing blood to simultaneously drain from the second tube into a barrel marked for medical waste.

Ninety minutes later, when the fluid emerging from the drainage tube ran clear, devoid of blood, Faison switched off the pump. Removing the needles from the neck and then the tubing, he inserted them in a red medical-waste box, and he returned to the body, where he tied shut the incision with heavy-gauge embalmer's thread.

Faison moved to the foot of the body, removed the toe tag and checked the name on the tag against the paperwork brought by the funeral service driver: Lewis. He tossed aside the tag and retrieved a translucent orange bracelet from a box on the counter. A number had been written on the bracelet with a Magic Marker: 3426. Faison scribbled the number across the front of the folder and fastened the bracelet around the cadaver's left ankle.

The mortician flipped through the paperwork and began dividing it into two piles. Most of it -- the death certificate, information about notifying the next of kin once the ashes became available -- he earmarked for Essie Feldman's office on G level. For his own files, Faison copied a few documents and placed them in an office cabinet. Faison scanned the obituary tucked into the folder and learned the man he'd just embalmed had been an educator. A teacher, Faison thought, very appropriate. He placed the obit back in the folder; on a copy of the receipt left by the funeral service, he noted: "Good subject. Possible Medical Gross."

Abkin helped Faison place the body in a large, clear plastic bag. They transferred Number 3426 to the gurney, which Faison then wheeled back into the refrigerator, officially designated on the building registrar as Room A526B.

On the wall above the clutter of folders, memorandums, written requests for donor forms, half-finished letters, partially completed syllabuses and other academic flotsam littering Essie Feldman's work area hung an enlarged photocopy declaring: "A Clean Desk Is a Sign of a Sick Mind." That being the case, Feldman was the picture of mental health.

The morning following the embalming, Faison deposited Number 3426's folder atop the pile and spent a few moments with Feldman catching up on the latest gossip. All anatomy department scuttlebutt passed through Feldman, whose ebullience -- everyone, save the department chairman, Dr. John H. Siegel, received the same salutation, "honey" -- penetrated the gravitas that permeated the halls of medical education. Flighty in personality and stylish in dress, Feldman stood out in a recondite atmosphere where grave demeanors were as common as white lab coats. Given her personality, Essie Feldman would, on the surface, seem an unlikely liaison between the medical school and the general public when it came to a topic most people are loath to discuss: death and its aftermath.

Feldman hadn't been predisposed to counsel the living about that which would transpire after they died; instead, the position chose her. In 1969, Feldman first reported for duty at the medical school in the capacity of secretary, and to the payroll department, a secretary she would remain during a tenure that would eventually exceed thirty years.

On Essie Feldman's first day on the job, the New Jersey College of Medicine, as it was then known, had been operational barely two years. The school was the offspring of the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry, which, in 1956, had the distinction of being New Jersey's first medical school. Several reasons have been advanced as to why New Jersey didn't have a school of medicine until the last half of the twentieth century, the most popular being that it took that long for the state's legislators to reject antivivisection statutes imposed by their Puritan political forebears. For whatever reason, New Jersey politicians believed laws designed to prevent the mutilation of animals applied also to the dissection of human cadavers.

Academically and also by the real barometer used to evaluate the success of medical schools -- securing federal grant money -- Seton Hall was an unqualified success. Its Jersey City campus, perched on the Hudson River overlooking the Manhattan skyline, proved to be a magnet for leading researchers, many of whom abandoned the epicenter of U.S. medical research -- Boston -- to join the fledgling school. Unfortunately, the school's bottom line did not match its achievements in the classroom and laboratory. Start-up costs far exceeded expectations, and even the federal grants couldn't stave off the fiscal reality of operating a medical school. It didn't take long for the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry, under the domain of the Catholic university in South Orange bearing the same name, to realize its books would never balance. By the early 1960s, the school started casting for a benefactor to bail it out; five years later Seton Hall's knight arrived in the form of the State of New Jersey.

The team undertaking the state's first order of business, finding a site to relocate the campus, settled on a 150-acre estate in yet-to-be-suburbanized Morris County. Located in the northwest quadrant of the state, the property offered everything but an ethnically diverse employment pool. Exploiting Morris County's shortcoming, Newark's Democratic mayor Hugh Addonizio presented the Democratically controlled state legislature with an alternative: a city with an existing ethnic workforce to staff a major medical school and hospital complex and, for the campus's construction, contracts that would provide jobs for thousands of laborers represented by the unions that greased the wheels of New Jersey Democratic machine politics. To make room for the medical school and hospital, Addonizio promised to condemn 150 acres in the Central Ward, just west of downtown.

The state legislature may have embraced Addonizio's plan, but not so the one thousand men, women and children residing within the boundaries of those six square impoverished and crime-infested city blocks. They stood to lose their homes. In July of 1967, as Addonizio's recommendation moved closer to reality, their anger, aggravated by multiple other factors, exploded into three nights of mayhem that left twenty-six dead.

Two months later, a medical school that didn't want to be there welcomed its first class of students to a neighborhood that didn't want them. Many years passed before the Central Ward accepted the school and medical center, and despite outreach programs that in 1994 earned it an Outstanding Community Service Award from the American Association of Medical Colleges, to this day the resentment among some residents continues to run so deep that they profess to prefer dying in an ambulance en route to Beth Israel Hospital, five miles away, than accept treatment at the UMDNJ-University Hospital in their own backyard.

The relocation to Newark cost the medical school dearly. Much of the faculty abandoned the institution, and with them went federal research funds and burgeoning prestige.

Among those making the move from Jersey City to Newark was a young and theatrical anatomy instructor named Anthony Boccabella. A self-described "hotshot," Boccabella tended to pepper his lectures with double entendres. Given the subject, the possibilities were endless. He was no less flamboyant outside the classroom, boasting of being the first medical student ever to arrive at the University of Iowa piloting his own plane. Later, while serving in the joint capacity of administrator and instructor at NJMS, he obtained a law degree, a pursuit he credited to being made to feel like a black sheep in a family of lawyers.

In 1971, a year after the New Jersey Medical School was folded into the statewide system of health education facilities now known as the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Boccabella became the chairman of the anatomy department. He would have preferred to focus on his field of expertise, endocrinology, the study of the thyroid, pituitary and other endocrine glands. Still, he appreciated the value of anatomy as the basic foundation of medical school and medical practice. "The rest is just dressing," he fondly pointed out.

During its brief tenure, Seton Hall suffered no shortage of cadavers. Boccabella recalled that most "were not there voluntarily," a polite way of saying the bodies had been secured from morgues. When the state uprooted the Jersey City facility, the corpses were brought to Newark along with desks, examining tables and other amenities crucial to the teaching of medicine.

The surplus no longer existed by the time Boccabella took over the program. Then, as now, four to one is the accepted ratio of medical students to cadavers in domestic human anatomy labs, and rarely in U.S. schools are more than four students assigned to a table. At some European schools, the students aren't quite as fortunate, with eight or more assigned to a single table. More unfavorable are the conditions in European countries that lack an adequate system for securing bodies, a situation which dictates that instructors dissect while students are relegated to the role of spectators. In the United States, Boccabella observed, students get "hands-on experience. They're able to play with it, cut through it and learn from the body. We're very, very lucky in this country."

In 1971, the dearth of cadavers in Newark nearly forced Boccabella to adopt the European custom. At each table, six medical students and one dental student worked on a single cadaver. The dental students dissected the head; the medical students studied the rest of the body. With the situation reaching the "crisis" stage, Boccabella undertook a desperate move.

Inspired by medical science's advances in the field of transplantation, Americans were just becoming aware of organ donations. As a scientist, Boccabella knew of an active registry in Washington listing the names of men and women who wished to donate, postmortem, their corneas. Playing a hunch, Boccabella contacted the registry. If these people were willing to pledge their corneas, he reasoned, perhaps they'd be amenable to contributing their entire bodies. A "gracious and unthinking" clerk provided Boccabella with precisely what he desired: the names of ten thousand New Jerseyans on the registry. Before the year was out, all ten thousand received from Boccabella a "passionate" letter.

Simultaneous to dispatching the letter, Boccabella began making the rounds of the state's burial societies, organizations of senior citizens banded together to minimize the high cost of death. He started his speech with an appeal to altruism, calling the donation of a body a gift in perpetuity, an unselfish act of ultimate benefit to every man, woman and child healed by the physician who profited from its myriad lessons. Boccabella assured his audience that in the lab they would be granted complete anonymity. Neither faculty nor students would know their identities. Boccabella followed the entreaty with an offer he hoped they'd find difficult to refuse: a postdissection cremation paid in full by the State of New Jersey. After cremation, he promised the ashes would be returned to the families for disposal as they saw fit.

From Sussex County, in the farthest corner of the state, to Cape May, New Jersey's southernmost point, Boccabella delivered his spiel. On the power of personality, he soon had people discussing openly a subject previously avoided or dealt with surreptitiously.

His name became a euphemism, a punch line: A husband and wife who jointly willed their bodies to NJMS used to joke it was time to "call Dr. Boccabella" whenever one of them was laid low by a cold or other assorted minor maladies.

As often as not, Boccabella could count on at least two or three burial society members to bring an attractive next of kin to a meeting. Recently divorced and constantly on the make, Boccabella sought them out after his presentation to inquire if they'd enjoyed his discourse. Those responding in the affirmative received a donor application; those who filled it out on the spot risked subjecting themselves to the doctor sidling up and whispering: "I already own your body and I promise to take care of it, so why wait?"

One of the worst pickup lines in history notwithstanding, Boccabella's sales pitch had the desired effect. The donor application forms that began to trickle in soon reached flood level. Unable to handle the flow, the department chair turned to his secretary.

Essie Feldman, with no training in medicine and no experience dealing with the imminence of death, received from Boccabella cursory instructions on how to respond to prospective donors. Feldman turned out to be such a natural that, before long, she was in charge of the cadaver procurement program.

The job required a gentle touch and Essie Feldman had it. She became expert at the art of reassurance, especially, as was often the case, when a donor had second thoughts about his or her decision. In most cases it was a loved one who gave donors pause, not so much spouses -- a surprising number of husbands and wives submitted donor forms in tandem -- as sons and daughters. Children seemed to have the most difficulty wrapping their minds around the idea of what became of a human body donated to science. Sometimes Feldman spoke directly with the conflicted party and explained, as best she could, the program's importance. Usually, the appeal worked; when it didn't, Feldman cast no aspersions. It's important, she'd tell those withdrawing their names from the donor file, that everyone in the family be comfortable with the decision.

Although contact between Feldman and donors was limited almost entirely to mail and telephone, a personal relationship sometimes developed between a benefactor and the woman to whom he or she had entrusted his or her body. They'd relay news of weddings and births and anniversaries. One man sent vacation snapshots from ports of call around the world. "Maybe I'll see you soon, Essie!" he'd scribble jokingly across the back of the photos. After he died, his family invited Feldman to his memorial service. She attended.

Essie Feldman's job also brought with it a fair amount of sadness. The task she performed was the result of a decision predicated on an issue troublesome to contemplate -- human beings tend to shy away from considerations of what lies beyond this mortal coil -- and even more difficult to articulate. Still, after a time, Feldman noticed a trend: Most of the donors were college-educated, and according to handwritten addenda or notations on the forms, the majority also participated actively in mainstream religions.

Occasionally, she'd speak with a man or woman who expressed the wish that by making a donation someone else would be spared some level of pain and suffering. One afternoon she took a call from a woman who, in a halting voice, detailed a twenty-year battle with schizophrenia. "Have you any interest in examining a broken mind?" she inquired. Feldman assured the woman -- in her late thirties, she was far younger than the people who usually contacted Feldman -- that her gift would be routed to scientists conducting neurological research. The woman began to weep and then regained her composure. "Thank you, thank you," she said quietly. "I don't want what happened to me to happen to anyone else."

Of course, Feldman's life was not always the stuff of high drama. Most of the time, her workload filled the description ascribed to the job by the payroll department. In the eyes of the State of New Jersey, which paid her salary, Essie Feldman was a secretary. Meaning a good portion of each day was devoted to routinely filing paperwork submitted by men and women who'd made a remarkable and difficult decision.

Such was the case on April 3, 1997, when Roger Faison walked into her office and plopped Number 3426's folder on the ever-present stack of papers atop her desk. Later that day, after Feldman entered on the filing tab the name of the deceased and the number assigned to the cadaver, she dutifully placed the folder in a file cabinet. There, Number 3426's dossier would remain until Feldman received word from Faison that the body, by either advancing medical science through research or serving as an anatomical blueprint for a quartet of medical students, was being dispatched to the crematorium.

Upon the return of the remains to the medical school, Feldman would swing into action again, contacting the family, informing them to soon expect a package the size of a shoe box. On average, two years passed between the time NJMS received a body and the follow-up letter from Essie Feldman. A lot can happen in two years: Next of kin occasionally move without providing a forwarding address; older relatives often join their loved ones in death. Stubbornly determined, Feldman went to great lengths in the effort to find someone, anyone, to properly disperse the ashes, in one instance devoting six years to the search for a sole, surviving son. She finally located him in the Midwest.

The ashes of the men and women whose relatives eluded Feldman's dragnet were stacked four high on a shelved rack in a hallway outside Faison's office in the basement. When the number of boxes approached two hundred, Faison transported them to a Linden cemetery for interment in a special plot overseen by the medical school. For years, Faison had urged the administration to commemorate the site with a small marker acknowledging the gift of those interred there, and finally, in 1999, the school accommodated him.

For eighty-nine weeks, Number 3426 remained in the refrigeration unit. In early December 1998, Faison started to review his files, setting aside those marked "Possible Medical Gross." In choosing bodies for Medical Gross and Developmental Anatomy, Faison knew what he was looking for: the elusive "AA" ratings. And Number 3426 fit the bill.

Six days before Christmas, Faison and Abkin removed Number 3426 from the refrigerator and placed the body on a stainless-steel tray measuring thirty inches by seventy-five inches, aerated at the bottom by twenty-eight drainage holes. Placing the tray on a gurney, Faison and Abkin covered Number 3426 from head to toe with five frayed towels and wheeled the gurney onto a freight elevator located just outside the entrance to the embalming room. When the gurneys in the elevator numbered three, Faison turned his key and pushed the button marked B. At the B level, the doors opened into the supply room attached to the gross anatomy laboratory serving the students of the New Jersey Medical School.

The NJMS laboratory is actually four interconnected laboratories, lettered A, B, C, D, each with eleven dissection tables. Lab A is tucked off by itself. The other three form an inverted F. Along the spine of the F are light boxes, a place where the study of the dead is supplemented by photographic representations of the living: X rays, magnetic resonance images (MRIs) and CAT scans.

With a dropped ceiling, fluorescent lighting and no windows, the gross anatomy lab is mundane, sterile. No art adorns the walls. Only the orange storage cabinets and the stained orange and yellow cushions on the rolling chairs clumped around the dissection tables break the monotony of the room's dominant color, off-white.

The tables, $3,800 new, stand forty-two inches high when the hoods are pulled back and secured below the table. When the hood is closed, it raises the height of the table to sixty inches. Anyone looking at the five-sided beveled hood would know precisely what lies inside.

By the afternoon of December 19, Faison and Abkin were half finished with their task. With the tables in Labs A and B already occupied, they began filling Lab C. Two at a time, they took the three gurneys from the elevator through Lab B into Lab C. Number 3426 was wheeled by Faison to the last table in the first row of the room.

Joined by Abkin, Faison counted to three and the two men lifted the tray onto Table 26. Wordlessly, Faison shut the hood and began pushing the gurney back to the elevator. Eighteen AA-rated bodies remained in the basement. Roger Faison checked his watch and did a quick calculation: Six more trips, and then, finally, he could begin his Christmas break.

Copyright © 2001 by Steve Giegerich

Recenzii

American Way magazine Appalling, funny, sobering and deeply moving, the story is a vivid reminder that we all are destined to a common fate, but our good works need not end in death.

Publishers Weekly Sensitive, provocative...essential reading for anyone considering a career in medicine.

The Plain Dealer (Cleveland) Compelling...packed with details about the process of medical education as well as the ordeals physicians undergo in training.

David A. Kornhauser, D.O. family practice physician, Milwaukee, Wisconsin Body of Knowledge reminds us that with all of the technological advances medicine has made, medicine's foundation is based on the philosophical and a deep understanding of the human body.

Publishers Weekly Sensitive, provocative...essential reading for anyone considering a career in medicine.

The Plain Dealer (Cleveland) Compelling...packed with details about the process of medical education as well as the ordeals physicians undergo in training.

David A. Kornhauser, D.O. family practice physician, Milwaukee, Wisconsin Body of Knowledge reminds us that with all of the technological advances medicine has made, medicine's foundation is based on the philosophical and a deep understanding of the human body.