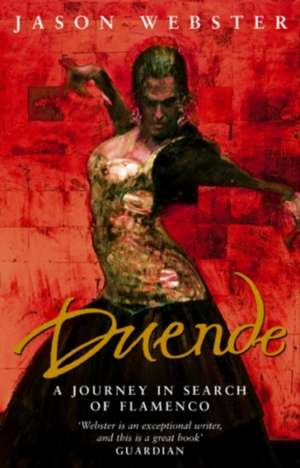

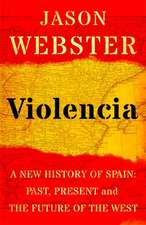

Duende

Autor Jason Websteren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2003

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 68.46 lei 26-32 zile | +23.68 lei 10-14 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – 31 dec 2003 | 68.46 lei 26-32 zile | +23.68 lei 10-14 zile |

| BROADWAY BOOKS – 29 feb 2004 | 108.72 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 68.46 lei

Preț vechi: 82.09 lei

-17% Nou

Puncte Express: 103

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.10€ • 13.71$ • 10.84£

13.10€ • 13.71$ • 10.84£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20-26 martie

Livrare express 04-08 martie pentru 33.67 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780552999977

ISBN-10: 0552999970

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 128 x 198 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0552999970

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 128 x 198 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

JASON WEBSTER was born near San Francisco and later moved to Europe as a child, living in England and Germany. He eventually ended up in Alexandria, Egypt, and then Spain, where he learned flamenco guitar and where he has been based on and off for the past ten years. He currently lives in Valencia, Spain, with the flamenco dancer Salud.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

Por Fandango

Yo como tu no encuentro ninguna,

mujer, con quien compararte;

solo he visto, por fortuna,

a una en un estandarte

y a los pies lleva la luna.

I've found nobody

to compare to you, woman;

only one other seen, fortunately,

on a church banner

with the moon at her feet.

A large woman stands up at the back of the stage and approaches the audience as the guitars play on. Raising an arm above her head, she stamps her foot hard, sweeps her hand down sharply to the side, and stares at us in defiance. The music stops and everyone falls silent.

Power emanates from her across the square. Breathing hard, legs rooted to the ground, chin raised, eyes bright, her face a vivid expression of pain. Everyone in the audience focuses on her as she stands motionless, leaning forward slightly, head thrust back, black hair falling loosely over her dark yellow dress. Stretching her arms down at her sides, she tenses her hands open, as though receiving or absorbing some invisible energy. For a moment I think she might never move, need never move even, so strong is the spell she has cast over us. Then, slowly, she lowers her head till it rests on her chest.

A sound begins from somewhere, low and deep: a human voice resonating with complex harmonies locked into a single note. I assume it is coming from the stage, but the song--if song it is--seems to be unprojected, effortlessly filling the space around us like water. It shocks me, as if some long-dormant, primitive, and troubled part of myself is being forced into wakefulness against its will. I have never felt anything like this before and struggle to comprehend as previously unfelt or forgotten emotions begin flowing through me, released by the trigger of the music. My eyes fixed ahead, I watch as the woman lifts her face once more, her mouth partly open, and I realize that the sound is coming from her.

She is singing. But there is no sweet voice, no pleasant melody, no recognizable tune at all. It is more like a scream, a cry, or a shout. Behind her the guitarists begin playing with short, rapid beats, fingers rippling over the strings in strange Moorish-sounding chords. The woman's voice lilts like a muezzin's call to prayer.

I am held by the music, as though any separation between myself and the rhythm has disappeared. A fat woman singing onstage, dancing in a way that seems as if she is barely moving, yet I feel she is stepping inside something and drawing me in with her. A chill, like a rippling sensation, moves up to my eyes. Tears begin to well up, while the cry from her lungs finds an echo within me and makes me want to shout along with her. The hairs on my skin stand on end, blood drains to my feet. I am rooted to the spot, suspended between the emotion being drawn out of me, as though bypassing my mind, and the shame of what I am feeling.

The song continues and I become aware that others in the audience are experiencing the same. I can tell by the expressions on their faces, a certain look in their eyes, and simply feeling it sweep around us all in a second, like a trance. Then the cries begin as she finds the echo inside us: shouts of "Ole," "Arsa," "Eso es." Some whisper under their breath, others shout, thick veins pulsating in their necks. The woman fills us, and the evening around us, with a sense of another space.

The song ends, and the audience breaks out into spontaneous, ecstatic applause. It is an emotional release, the greatest one might ever imagine. Pedro leans over to me.

"Did you feel it?" he asks.

----------------------------------------------------

The plane flew in over the dust-yellow land. Mountains like pieces of rock half buried in the sand pushed their way up from the earth, casting long shadows over the landscape as the sun descended behind us. I stared down through the window at the empty space below: arid semidesert banked by an azure sea, with a promise of balmy, jasmine-scented nights.

Pedro was my only contact in Spain and therefore, I reasoned, a natural starting point for my journey. A friend of a friend and a university lecturer in Arabic, he greeted me at the airport like a lost son, embracing me warmly in the arrivals hall, and quickly gave me a new name: Mi querido Watson. He said my surname reminded him of the old Sherlock Holmes films and the time he'd spent living on Baker Street as a youth. I couldn't see the similarity myself.

"Don't worry. Be khappy," he laughed.

He took me to his house just to the north of Alicante. His father had built it in the fifties: a white rectangular villa with bright green shutters, verandas, and balconies. I was given the top floor and told I could stay as long as I needed. From the roof you could see the sea stretching across to Algeria. Africa seemed very close.

The garden was straight out of A Thousand and One Nights. Date palms stood next to pungent rosemary bushes in an oasis filled with fig trees, jasmine, delicate red and pink roses, pomegranate trees, and row upon row of lemon and orange trees. The jasmine had been trained over the years to create a covered sanctuary where we could sit away from the intense midday sun, half intoxicated by the perfume circling around us. Pedro insisted we sit together, talking and drinking tea from bone china cups. At first I was happy to acclimatize in this leisurely fashion. After a few days, though, it was frustrating. I wanted to get going, to begin my flamenco adventure, but my host was a man who liked to take his time over any task at hand, always deliberate and careful in everything he did.

"You can't run away from your own feet," he said, determined to hold me down there in his garden, to stop me from rushing around before I knew where to look.

He would talk nonstop, one story flowing into another in a constant stream of tales and anecdotes. I could hardly get a word in, and when he let me, it was only to fill in some detail, the name of a town or a person we both knew. At first our conversation centered on Arabic, which we had both studied, but it soon moved on to other subjects. He talked of his love of England, the folklore of Alicante, astronomy, and recipes for chicken broth. He told me everything I would ever want to know about the ancient Roman settlement over the road, and how one of his cousins had been a Fascist and the other a Republican but they never let politics interfere in family life. He spoke of the haunting beauty of the ancient statue of a woman's head that had been found in the nearby town of Elche.

"No one knows who made her! The Greeks? The Phoenicians? The Iberians? It's a mystery."

And of course, he talked about Arabic poetry, quoting verses of Ibn Hazm, Al-Russafi, and Abu al-Hashash al-Munsafi. Dark would fall, the scent of the jasmine giving way to the galan de noche, the gentleman of the night, offering up its stronger more energetic scent, and we would still be there, tales of the Alhambra hanging in the night air.

"You will go there one day," Pedro said, swapping in and out between English and Spanish as my ear grew used to his voice. "You will see Granada, and it will change you forever." And he pursed his moustachioed lips momentarily before downing his chamomile tea.

"Don't worry. Be khappy."

----------------------------------------------------

The exact origins of flamenco are uncertain. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are often cited as the period when it started to take shape, but the Roman poet Juvenal referred to Cadiz girls in Rome--puellae gaditanae--who performed dances with bronze castanets in the time of the emperor Trajan. For the poet and flamencologist Domingo Manfredi, writing in the 1960s, this was evidence enough to date flamenco back to classical times. Others have suggested a multiple origin, pointing to the rich mixture of cultures--Iberian, Phoenician, Visigothic, Greek, Roman, Arabic--that has flourished in Spain over the centuries. The composer Manuel de Falla specified the Moorish invasion in 711, the Spanish Church's adoption of the Byzantine liturgical chant, and the arrival of the Gypsies, bringing with them enharmonic influences from Indian songs, as the key factors in the development of flamenco.

The role of the Gypsies is crucial but perhaps the least understood. First, there is the question of when they actually arrived in Spain. There appear to have been at least two waves: one from North Africa during the Islamic period, and another from France in the years shortly before the fall of Granada in 1492. No one doubts that they have played a major role in the development of flamenco; the question is, to what extent? Are they its sole creators? If so, why aren't there more obvious echoes in Gypsy music from other countries? Did they just take already existing folk songs and transform them by playing them with their own interpretation and style? Some have tried to divide palos--the different styles and songs within flamenco--into those of supposedly Gypsy and non-Gypsy origin. But then others place some palos outside flamenco altogether. Sevillanas, the essence for most foreigners of "typical Spanish" flamenco, with clacking castanets and dancers in long frilly dresses, would be classified by many aficionados as "folklore," not as flamenco.

For most flamencos, though, these things are intuited, if thought about at all. Moorish or Jewish, Gypsy or Andalusian, there is an instinctive feel for flamenco, making it easy to recognize, if difficult to pin down. Part of it has to do with being away from the mainstream, or on the outside. For the past two hundred years at least, flamenco has been the music and dance of outcasts, people on the margins of Spanish, and particularly Andalusian, society. From which, perhaps, stems the natural affinity with Gypsies, and accounts for the large number of songs about injustice or going to jail:

A las rejas de la carcel

no me vengas a llora.

Ya que no me quitas pena

no me la vengas a da.

Don't come crying

to the prison bars.

Since you can't ease my pain

don't come here making it worse.

The only certainty about flamenco is that it began in Andalusia and remains to this day Andalusian, despite spreading across Spain and around the world. Madrid, and to a lesser extent Barcelona, have recently become flamenco centers, but only by importing southern communities and culture. Andalusia, with its poverty, arid heat, and proximity to Africa, remains the eternal reference point and true source.

----------------------------------------------------

"Drink this, Watson. It will make you clean on the inside."

We spent mornings at Pedro's house picking ripe figs, oranges, and pomegranates from his orchard to make exotic juices for breakfast.

He had managed to create on a small scale what I imagined the great Arab gardens of the past had been like. The Moorish conquerors had a desert people's natural love of gardens, and their irrigation systems had turned parts of the eastern coast into one of the most fertile areas in Europe. When Philip III had the last remaining Muslims thrown out of Valencia in a fit of pique at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the local economy collapsed, as the only people with the necessary gardening know-how--built up over nine hundred years--had been forced from their homes into exile. Some said the knowledge had never been fully recovered, but sitting in Pedro's garden, I was prepared to believe they were wrong. Here you could rest, a deep rest that saturated the entire body. And slowly I began to feel myself falling under the spell of the place, days with no beginning or end, my mission almost forgotten.

But then with a jolt it would return, like a violent itch. There were things to be done. I must be on the move. I wanted to start learning flamenco. Alicante, the home of my only contact, had seemed the obvious place to start, but on my few walks around town I had found no flamenco bars, no guitarists idling in the shade, no dancers practicing their steps on the street, nothing. At that time I had only a vague idea that flamenco was to be found in Andalusia, and looking at the map, Alicante hadn't seemed that far away. Surely I would find evidence of it on every street corner. But as my limited searching led nowhere, I began to understand how ill-prepared I had been. I had no idea where to start or what to expect. Pedro would know what I needed to do.

No sooner had I found him, though, watering the date palms and feeding TV, his exquisite white-furred cat, than he distracted me with yet another story. The little local train--the trenet--passing next to the garden, jolted us out of our chatter as it thundered along its single track, belching out black diesel fumes.

"Ah, mi querido Watson," said Pedro as our lazy afternoon was shattered once again, "qu'est-ce qu'on peut faire?" And he shrugged his shoulders and pouted in a Gallic manner, a hangover from his student days in France. He liked to remind me that it was back in Paris that he had been given a part in the film What's New Pussycat?--a token Spaniard at a fancy dress party.

"Hombre, they wanted me to take a bigger role, but I wasn't interested. I was too busy trying to get to know the girls at the Sorbonne." His eyes twinkled.

For an erstwhile movie star and seducer of Parisian women, Pedro hardly looked the part. Age had taken its toll. Take away the belly and the gray hair and . . . maybe. But it required a leap of the imagination. Perhaps the girls were big on moustaches back then.

And so I spent these first days at Pedro's acclimatizing as best I could to the new environment. Spanish was relatively easy to pick up--having already learned Italian and Arabic, it felt more like I was remembering it than learning it for the first time, and within a week English had all but disappeared. I learned how to cook tortilla de patatas and cocido (a type of stew), weeding the garden while Pedro gave his classes at the university, walking over dusty fields to the beach, and swimming in the late summer sun. But all the while, at the back of my mind, a nagging, restless voice was pressing me to begin my search in earnest.

----------------------------------------------------

"So you want to know about flamenco?" Pedro asked one morning at breakfast. I heaved a sigh of relief. He stared into the sky and began to recite:

Empieza el llanto

de la guitarra.

Se rompen las copas

de la madrugada.

Empieza el llanto

de la guitarra.

Es inutil

callarla.

The cry of the guitar begins.

In the early morning,

wine glasses shatter.

The cry of the guitar begins.

Useless

to silence it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Por Fandango

Yo como tu no encuentro ninguna,

mujer, con quien compararte;

solo he visto, por fortuna,

a una en un estandarte

y a los pies lleva la luna.

I've found nobody

to compare to you, woman;

only one other seen, fortunately,

on a church banner

with the moon at her feet.

A large woman stands up at the back of the stage and approaches the audience as the guitars play on. Raising an arm above her head, she stamps her foot hard, sweeps her hand down sharply to the side, and stares at us in defiance. The music stops and everyone falls silent.

Power emanates from her across the square. Breathing hard, legs rooted to the ground, chin raised, eyes bright, her face a vivid expression of pain. Everyone in the audience focuses on her as she stands motionless, leaning forward slightly, head thrust back, black hair falling loosely over her dark yellow dress. Stretching her arms down at her sides, she tenses her hands open, as though receiving or absorbing some invisible energy. For a moment I think she might never move, need never move even, so strong is the spell she has cast over us. Then, slowly, she lowers her head till it rests on her chest.

A sound begins from somewhere, low and deep: a human voice resonating with complex harmonies locked into a single note. I assume it is coming from the stage, but the song--if song it is--seems to be unprojected, effortlessly filling the space around us like water. It shocks me, as if some long-dormant, primitive, and troubled part of myself is being forced into wakefulness against its will. I have never felt anything like this before and struggle to comprehend as previously unfelt or forgotten emotions begin flowing through me, released by the trigger of the music. My eyes fixed ahead, I watch as the woman lifts her face once more, her mouth partly open, and I realize that the sound is coming from her.

She is singing. But there is no sweet voice, no pleasant melody, no recognizable tune at all. It is more like a scream, a cry, or a shout. Behind her the guitarists begin playing with short, rapid beats, fingers rippling over the strings in strange Moorish-sounding chords. The woman's voice lilts like a muezzin's call to prayer.

I am held by the music, as though any separation between myself and the rhythm has disappeared. A fat woman singing onstage, dancing in a way that seems as if she is barely moving, yet I feel she is stepping inside something and drawing me in with her. A chill, like a rippling sensation, moves up to my eyes. Tears begin to well up, while the cry from her lungs finds an echo within me and makes me want to shout along with her. The hairs on my skin stand on end, blood drains to my feet. I am rooted to the spot, suspended between the emotion being drawn out of me, as though bypassing my mind, and the shame of what I am feeling.

The song continues and I become aware that others in the audience are experiencing the same. I can tell by the expressions on their faces, a certain look in their eyes, and simply feeling it sweep around us all in a second, like a trance. Then the cries begin as she finds the echo inside us: shouts of "Ole," "Arsa," "Eso es." Some whisper under their breath, others shout, thick veins pulsating in their necks. The woman fills us, and the evening around us, with a sense of another space.

The song ends, and the audience breaks out into spontaneous, ecstatic applause. It is an emotional release, the greatest one might ever imagine. Pedro leans over to me.

"Did you feel it?" he asks.

----------------------------------------------------

The plane flew in over the dust-yellow land. Mountains like pieces of rock half buried in the sand pushed their way up from the earth, casting long shadows over the landscape as the sun descended behind us. I stared down through the window at the empty space below: arid semidesert banked by an azure sea, with a promise of balmy, jasmine-scented nights.

Pedro was my only contact in Spain and therefore, I reasoned, a natural starting point for my journey. A friend of a friend and a university lecturer in Arabic, he greeted me at the airport like a lost son, embracing me warmly in the arrivals hall, and quickly gave me a new name: Mi querido Watson. He said my surname reminded him of the old Sherlock Holmes films and the time he'd spent living on Baker Street as a youth. I couldn't see the similarity myself.

"Don't worry. Be khappy," he laughed.

He took me to his house just to the north of Alicante. His father had built it in the fifties: a white rectangular villa with bright green shutters, verandas, and balconies. I was given the top floor and told I could stay as long as I needed. From the roof you could see the sea stretching across to Algeria. Africa seemed very close.

The garden was straight out of A Thousand and One Nights. Date palms stood next to pungent rosemary bushes in an oasis filled with fig trees, jasmine, delicate red and pink roses, pomegranate trees, and row upon row of lemon and orange trees. The jasmine had been trained over the years to create a covered sanctuary where we could sit away from the intense midday sun, half intoxicated by the perfume circling around us. Pedro insisted we sit together, talking and drinking tea from bone china cups. At first I was happy to acclimatize in this leisurely fashion. After a few days, though, it was frustrating. I wanted to get going, to begin my flamenco adventure, but my host was a man who liked to take his time over any task at hand, always deliberate and careful in everything he did.

"You can't run away from your own feet," he said, determined to hold me down there in his garden, to stop me from rushing around before I knew where to look.

He would talk nonstop, one story flowing into another in a constant stream of tales and anecdotes. I could hardly get a word in, and when he let me, it was only to fill in some detail, the name of a town or a person we both knew. At first our conversation centered on Arabic, which we had both studied, but it soon moved on to other subjects. He talked of his love of England, the folklore of Alicante, astronomy, and recipes for chicken broth. He told me everything I would ever want to know about the ancient Roman settlement over the road, and how one of his cousins had been a Fascist and the other a Republican but they never let politics interfere in family life. He spoke of the haunting beauty of the ancient statue of a woman's head that had been found in the nearby town of Elche.

"No one knows who made her! The Greeks? The Phoenicians? The Iberians? It's a mystery."

And of course, he talked about Arabic poetry, quoting verses of Ibn Hazm, Al-Russafi, and Abu al-Hashash al-Munsafi. Dark would fall, the scent of the jasmine giving way to the galan de noche, the gentleman of the night, offering up its stronger more energetic scent, and we would still be there, tales of the Alhambra hanging in the night air.

"You will go there one day," Pedro said, swapping in and out between English and Spanish as my ear grew used to his voice. "You will see Granada, and it will change you forever." And he pursed his moustachioed lips momentarily before downing his chamomile tea.

"Don't worry. Be khappy."

----------------------------------------------------

The exact origins of flamenco are uncertain. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are often cited as the period when it started to take shape, but the Roman poet Juvenal referred to Cadiz girls in Rome--puellae gaditanae--who performed dances with bronze castanets in the time of the emperor Trajan. For the poet and flamencologist Domingo Manfredi, writing in the 1960s, this was evidence enough to date flamenco back to classical times. Others have suggested a multiple origin, pointing to the rich mixture of cultures--Iberian, Phoenician, Visigothic, Greek, Roman, Arabic--that has flourished in Spain over the centuries. The composer Manuel de Falla specified the Moorish invasion in 711, the Spanish Church's adoption of the Byzantine liturgical chant, and the arrival of the Gypsies, bringing with them enharmonic influences from Indian songs, as the key factors in the development of flamenco.

The role of the Gypsies is crucial but perhaps the least understood. First, there is the question of when they actually arrived in Spain. There appear to have been at least two waves: one from North Africa during the Islamic period, and another from France in the years shortly before the fall of Granada in 1492. No one doubts that they have played a major role in the development of flamenco; the question is, to what extent? Are they its sole creators? If so, why aren't there more obvious echoes in Gypsy music from other countries? Did they just take already existing folk songs and transform them by playing them with their own interpretation and style? Some have tried to divide palos--the different styles and songs within flamenco--into those of supposedly Gypsy and non-Gypsy origin. But then others place some palos outside flamenco altogether. Sevillanas, the essence for most foreigners of "typical Spanish" flamenco, with clacking castanets and dancers in long frilly dresses, would be classified by many aficionados as "folklore," not as flamenco.

For most flamencos, though, these things are intuited, if thought about at all. Moorish or Jewish, Gypsy or Andalusian, there is an instinctive feel for flamenco, making it easy to recognize, if difficult to pin down. Part of it has to do with being away from the mainstream, or on the outside. For the past two hundred years at least, flamenco has been the music and dance of outcasts, people on the margins of Spanish, and particularly Andalusian, society. From which, perhaps, stems the natural affinity with Gypsies, and accounts for the large number of songs about injustice or going to jail:

A las rejas de la carcel

no me vengas a llora.

Ya que no me quitas pena

no me la vengas a da.

Don't come crying

to the prison bars.

Since you can't ease my pain

don't come here making it worse.

The only certainty about flamenco is that it began in Andalusia and remains to this day Andalusian, despite spreading across Spain and around the world. Madrid, and to a lesser extent Barcelona, have recently become flamenco centers, but only by importing southern communities and culture. Andalusia, with its poverty, arid heat, and proximity to Africa, remains the eternal reference point and true source.

----------------------------------------------------

"Drink this, Watson. It will make you clean on the inside."

We spent mornings at Pedro's house picking ripe figs, oranges, and pomegranates from his orchard to make exotic juices for breakfast.

He had managed to create on a small scale what I imagined the great Arab gardens of the past had been like. The Moorish conquerors had a desert people's natural love of gardens, and their irrigation systems had turned parts of the eastern coast into one of the most fertile areas in Europe. When Philip III had the last remaining Muslims thrown out of Valencia in a fit of pique at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the local economy collapsed, as the only people with the necessary gardening know-how--built up over nine hundred years--had been forced from their homes into exile. Some said the knowledge had never been fully recovered, but sitting in Pedro's garden, I was prepared to believe they were wrong. Here you could rest, a deep rest that saturated the entire body. And slowly I began to feel myself falling under the spell of the place, days with no beginning or end, my mission almost forgotten.

But then with a jolt it would return, like a violent itch. There were things to be done. I must be on the move. I wanted to start learning flamenco. Alicante, the home of my only contact, had seemed the obvious place to start, but on my few walks around town I had found no flamenco bars, no guitarists idling in the shade, no dancers practicing their steps on the street, nothing. At that time I had only a vague idea that flamenco was to be found in Andalusia, and looking at the map, Alicante hadn't seemed that far away. Surely I would find evidence of it on every street corner. But as my limited searching led nowhere, I began to understand how ill-prepared I had been. I had no idea where to start or what to expect. Pedro would know what I needed to do.

No sooner had I found him, though, watering the date palms and feeding TV, his exquisite white-furred cat, than he distracted me with yet another story. The little local train--the trenet--passing next to the garden, jolted us out of our chatter as it thundered along its single track, belching out black diesel fumes.

"Ah, mi querido Watson," said Pedro as our lazy afternoon was shattered once again, "qu'est-ce qu'on peut faire?" And he shrugged his shoulders and pouted in a Gallic manner, a hangover from his student days in France. He liked to remind me that it was back in Paris that he had been given a part in the film What's New Pussycat?--a token Spaniard at a fancy dress party.

"Hombre, they wanted me to take a bigger role, but I wasn't interested. I was too busy trying to get to know the girls at the Sorbonne." His eyes twinkled.

For an erstwhile movie star and seducer of Parisian women, Pedro hardly looked the part. Age had taken its toll. Take away the belly and the gray hair and . . . maybe. But it required a leap of the imagination. Perhaps the girls were big on moustaches back then.

And so I spent these first days at Pedro's acclimatizing as best I could to the new environment. Spanish was relatively easy to pick up--having already learned Italian and Arabic, it felt more like I was remembering it than learning it for the first time, and within a week English had all but disappeared. I learned how to cook tortilla de patatas and cocido (a type of stew), weeding the garden while Pedro gave his classes at the university, walking over dusty fields to the beach, and swimming in the late summer sun. But all the while, at the back of my mind, a nagging, restless voice was pressing me to begin my search in earnest.

----------------------------------------------------

"So you want to know about flamenco?" Pedro asked one morning at breakfast. I heaved a sigh of relief. He stared into the sky and began to recite:

Empieza el llanto

de la guitarra.

Se rompen las copas

de la madrugada.

Empieza el llanto

de la guitarra.

Es inutil

callarla.

The cry of the guitar begins.

In the early morning,

wine glasses shatter.

The cry of the guitar begins.

Useless

to silence it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“In this enjoyable Spanish travel memoir…Webster…fluidly interlac[es] his foreigner’s perspective with edgy and often perilous cravings to live of a genuine flamenco guitarist…Webster deserves praise for verbalizing an emotion that most people can only feel or imagine.” –Publishers Weekly

“A journey into the heart of flamenco, it is as vivid and colorful as an Almodovar film; it’ll leave you with a burning desire to head for Spain.” –Time Out (London)

“There are three great non-fiction books about Spain written by Englishmen. One is Laurie Lee's As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, the other two are by Gerald Brenan: The Spanish Labyrinth and South from Granada. In my view, Jason Webster's Duende:…is very nearly up there in the pantheon….A powerful, dangerous book that will win many prizes.”

–Condé Nast Traveller (London)

“Jason Webster has immersed himself deep in a world where few outsiders have succeeded, and he writes about it in an engaging style. I found his descriptions of the Flamenco underworld irresistible, his characterizations deftly drawn, and his ideas and observations on Spain and the Spanish thoughtful and intriguing...I was drawn in straightaway, and although I hesitate to say this ... I couldn't put it down." -Chris Stewart, Author of Driving Over Lemons

“This is a thoroughly good read. An honest attempt to explain a consuming passion, it’s a book where fact is definitely stranger and more convincing than fiction.” -Living Spain

“A compelling account of a culture closed to most guiris (foreigners) and infinitely darker and more dramatic than the colourful tourist spectacles would have them believe.”

–The Observer (London)

“His descriptions of troubled modern day Spain are mesmerizing…” –Daily Express

“Jason Webster is an exceptional writer, and this is a great book.” –Sunday Telegraph

"For a first book, indeed for any book, Webster's writing has great assurance, and there are some superbly constructed moments...Duende is an impressive debut...We will be lucky if we see many such passionate and evocative travel books this year."–Sunday Times (London)

From the Hardcover edition.

“A journey into the heart of flamenco, it is as vivid and colorful as an Almodovar film; it’ll leave you with a burning desire to head for Spain.” –Time Out (London)

“There are three great non-fiction books about Spain written by Englishmen. One is Laurie Lee's As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, the other two are by Gerald Brenan: The Spanish Labyrinth and South from Granada. In my view, Jason Webster's Duende:…is very nearly up there in the pantheon….A powerful, dangerous book that will win many prizes.”

–Condé Nast Traveller (London)

“Jason Webster has immersed himself deep in a world where few outsiders have succeeded, and he writes about it in an engaging style. I found his descriptions of the Flamenco underworld irresistible, his characterizations deftly drawn, and his ideas and observations on Spain and the Spanish thoughtful and intriguing...I was drawn in straightaway, and although I hesitate to say this ... I couldn't put it down." -Chris Stewart, Author of Driving Over Lemons

“This is a thoroughly good read. An honest attempt to explain a consuming passion, it’s a book where fact is definitely stranger and more convincing than fiction.” -Living Spain

“A compelling account of a culture closed to most guiris (foreigners) and infinitely darker and more dramatic than the colourful tourist spectacles would have them believe.”

–The Observer (London)

“His descriptions of troubled modern day Spain are mesmerizing…” –Daily Express

“Jason Webster is an exceptional writer, and this is a great book.” –Sunday Telegraph

"For a first book, indeed for any book, Webster's writing has great assurance, and there are some superbly constructed moments...Duende is an impressive debut...We will be lucky if we see many such passionate and evocative travel books this year."–Sunday Times (London)

From the Hardcover edition.