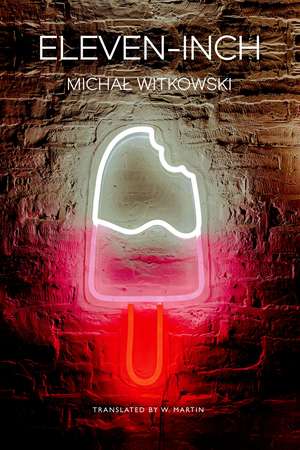

Eleven-Inch: The Pride List

Autor Michal Witkowski Traducere de W. Martinen Limba Engleză Hardback – 6 dec 2021

Western Europe, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall: Two queer teens from Eastern Europe journey to Vienna, then Zurich, in search of a better life as sex workers. They couldn’t be more different from each other. Milan, aka Dianka, a dreamy, passive naïf from Slovakia, drifts haplessly from one abusive sugar daddy to the next, whereas Michał, a sanguine pleasure-seeker from Poland, quickly masters the selfishness and ruthlessness that allow him to succeed in the wild, capitalist West—all the while taking advantage of the physical endowment for which he is dubbed “Eleven-Inch.” By turns impoverished and flush with their earnings, the two traverse a precarious new world of hustler bars, public toilets, and nights spent sleeping in train stations and parks or in the opulent homes of their wealthy clients. With campy wit and sensuous humor, Michał Witkowski explores in Eleven-Inch the transition from Soviet-style communism to neoliberal capitalism in Europe through the experiences of the most marginalized: destitute queers.

Preț: 150.48 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 226

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.80€ • 29.68$ • 24.32£

28.80€ • 29.68$ • 24.32£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 februarie

Livrare express 24-30 ianuarie pentru 34.45 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780857428912

ISBN-10: 0857428918

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.59 kg

Editura: Seagull Books

Colecția Seagull Books

Seria The Pride List

ISBN-10: 0857428918

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.59 kg

Editura: Seagull Books

Colecția Seagull Books

Seria The Pride List

Notă biografică

Michał Witkowski is a Polish author. His groundbreaking novel Lovetown was the first explicitly queer novel to be published in Polish and was longlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2011. He lives in Warsaw. W. Martin is a United States-born editor, educator, translator, and writer who lives in Berlin and Ramallah. His published translations from Polish include Michal Witkowski’s Lovetown.

Extras

She was on her own, in the metro, and her shoes were chafing her feet, so she couldn’t even go roaming around Vienna. So she hobbled over to Alfie’s Golden Mirror, the rent boy bar, sat down in a corner, and without drinking, without smoking, without eating, simply watched the goings-on, quietly humming Slovak rock songs to herself.

It was like a game of roulette: you might make five hundred schillings in a night and not a cent for the entire next week. Either way you’d sometimes have to sit there for hours before landing a customer. During which time you’d end up drinking five deliriously overpriced coffees, five Fantas, five beers, five whatever, because the bartender (Norma)made sure that the rent boys ordered at least one drink per hour. So, what you made in one day you’d spend over the course of five just sitting and waiting. And you’d be chainsmoking those Austrian cigarettes, Milde Sorte, which are extra light, but always give you headaches! Dianka watched the successful boys with envy, sitting there at the bar, stuffing their faces with enormous schnitzels and fries or potato salad or pork chops and fried eggs. And some-times they didn’t even have to pay for it because they were with some fat, bald grandpa with a wallet. And with beautiful, fresh lemon halves to squeeze on the meat, on the fries, on all that wonderful grub! She swallowed her own spit and smoked a cigarette she’d bummed off someone, which tasted like crap on an empty stomach. She wondered how long before they threw her out, since she wasn’t putting money in the till. Even if she did dig up a few schillings, she knew what would happen next—she’d trick once, then have nothing five nights in a row, she could lose everything. Even the Romanians had been dry for two weeks! Oh, and what Romanians they were! My God! Through their oversized, baggy, white trousers they showed Dianka what gorgeous, fat cocks they had. They stretched the stained fabric around them. In their broken German mixed with Russian, they asked her to see for herself, starved as they were—two weeks. They wanted schillings, cigarettes; but what could she give them? They were handsome and masculine, with- out that antiseptic look in their eyes, like the Austrians, Swiss, and Germans had; they were straight. Eighteen years old, swarthy, with bushy black eyebrows! But they reminded her a little of Gypsies, and Dianka was afraid of Gypsies, like the ones in Slovakia, who stood around and made bonfires, their eyes mirroring the flames . . .

An elderly customer named Dieter, a copy of Günter Grass’s The Rat and a Wiener Zeitung under his arm, made the rounds of the bar, looking like the professor from The Blue Angel. In a threadbare sports coat, with a little pipe. But he didn’t know what he wanted. He once called Dianka over to his table, bought her drinks, then said:

‘Heute bin ich müde, lass mich alleine. . . ’ Then they made a date for Wednesday, although Dianka really wasn’t sure he’d live that long.

Vincent is behind the bar today, a tall, likeable Austrian; Dianka and her ilk are good for business. Old torch songs waft out of the jukebox, even Edith Piaf. In the next room the rent boys play the slot machines. An unwashed, unattractive African is there. She stinks, and Dianka knows she’s homeless, that she got sucked into the vicious circle, and that she’ll end up there herself, too, if a miracle doesn’t happen tonight. Then that sweetheart Vincent gives a nod to the bouncer to escort the African discreetly off the premises. Outside, in the cold, you can’t smell the beer or vittles. There among the parked cars walk the boys who aren’t allowed into Alfie’s because they’re too poxy. The ones who didn’t want to give a cut of their earnings with the Czech mafia, so their faces got cut with razor blades. The ones who didn’t want to give the bartenders, Norma and Vincent, what they . . .

It was like a game of roulette: you might make five hundred schillings in a night and not a cent for the entire next week. Either way you’d sometimes have to sit there for hours before landing a customer. During which time you’d end up drinking five deliriously overpriced coffees, five Fantas, five beers, five whatever, because the bartender (Norma)made sure that the rent boys ordered at least one drink per hour. So, what you made in one day you’d spend over the course of five just sitting and waiting. And you’d be chainsmoking those Austrian cigarettes, Milde Sorte, which are extra light, but always give you headaches! Dianka watched the successful boys with envy, sitting there at the bar, stuffing their faces with enormous schnitzels and fries or potato salad or pork chops and fried eggs. And some-times they didn’t even have to pay for it because they were with some fat, bald grandpa with a wallet. And with beautiful, fresh lemon halves to squeeze on the meat, on the fries, on all that wonderful grub! She swallowed her own spit and smoked a cigarette she’d bummed off someone, which tasted like crap on an empty stomach. She wondered how long before they threw her out, since she wasn’t putting money in the till. Even if she did dig up a few schillings, she knew what would happen next—she’d trick once, then have nothing five nights in a row, she could lose everything. Even the Romanians had been dry for two weeks! Oh, and what Romanians they were! My God! Through their oversized, baggy, white trousers they showed Dianka what gorgeous, fat cocks they had. They stretched the stained fabric around them. In their broken German mixed with Russian, they asked her to see for herself, starved as they were—two weeks. They wanted schillings, cigarettes; but what could she give them? They were handsome and masculine, with- out that antiseptic look in their eyes, like the Austrians, Swiss, and Germans had; they were straight. Eighteen years old, swarthy, with bushy black eyebrows! But they reminded her a little of Gypsies, and Dianka was afraid of Gypsies, like the ones in Slovakia, who stood around and made bonfires, their eyes mirroring the flames . . .

An elderly customer named Dieter, a copy of Günter Grass’s The Rat and a Wiener Zeitung under his arm, made the rounds of the bar, looking like the professor from The Blue Angel. In a threadbare sports coat, with a little pipe. But he didn’t know what he wanted. He once called Dianka over to his table, bought her drinks, then said:

‘Heute bin ich müde, lass mich alleine. . . ’ Then they made a date for Wednesday, although Dianka really wasn’t sure he’d live that long.

Vincent is behind the bar today, a tall, likeable Austrian; Dianka and her ilk are good for business. Old torch songs waft out of the jukebox, even Edith Piaf. In the next room the rent boys play the slot machines. An unwashed, unattractive African is there. She stinks, and Dianka knows she’s homeless, that she got sucked into the vicious circle, and that she’ll end up there herself, too, if a miracle doesn’t happen tonight. Then that sweetheart Vincent gives a nod to the bouncer to escort the African discreetly off the premises. Outside, in the cold, you can’t smell the beer or vittles. There among the parked cars walk the boys who aren’t allowed into Alfie’s because they’re too poxy. The ones who didn’t want to give a cut of their earnings with the Czech mafia, so their faces got cut with razor blades. The ones who didn’t want to give the bartenders, Norma and Vincent, what they . . .

Recenzii

"An electrifying dive into a memorable demimonde."

"There is a charm in the author’s style of writing and the sharp use of wit and humour spreads over the whole story. . . . There is life breathed into every page, for which the credit also goes to the translator."

"Witkowski's novel is a king-size achievement in its own right."